Читать книгу No White Picket Fence - Robin C. Whittaker - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

THEATRE AND SOCIAL WORK

ОглавлениеIn Fredericton, New Brunswick, in recent years, St. Thomas University’s five-decades-old student production company, Theatre St. Thomas (TST), has nurtured an increasing interest in offering, and in a few cases developing and premiering, socially relevant plays that speak to immediate and pressing interests.

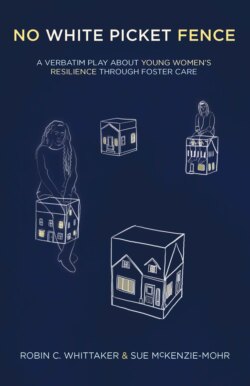

TST’s flexible Black Box Theatre space allows the company to map out myriad playing areas to generate unique relationships between plays and audiences. In the case of No White Picket Fence, TST created an enduring text in collaboration with Dr. Suzanne (Sue) McKenzie-Mohr from voices of those who are often silenced, with the aim of spreading their perspectives to generate social change.

Born of a research project conducted by Sue, a faculty member in the St. Thomas University School of Social Work, No White Picket Fence is “verbatim theatre,” a non-traditional and powerful means by which people’s accounts of their experiences – stories that are seldom heard – can be shared.

Many studies have focused on adverse outcomes for young adults after exiting care. Having often spent years in challenging home situations, followed by limited stability in the care system and inadequate supports through their transition into adulthood, many youth have faced significant challenges after their time in care, including higher-than-average rates of poverty, unemployment, housing instability, and victimization. Without question, such challenges are important for us to understand. However, a smaller number of researchers have studied factors that support youths’ resilience and growth after their time in care.

When Sue envisioned this research project in 2014, her hope was to hear directly from young women who had left the care system in their teens and had come to live well, and to offer them the opportunity to share at length about their experiences. Importantly, there were no imposed criteria for “living well.” Rather, understanding oneself to be living well at the time of the interviews was requisite to participation in the study.

In total, ten young women (average age twenty-five years) agreed to participate in the research. The broad question asked early in each individual interview was: “Could you tell me about your experience from your time in care to your current time of living well? You can begin wherever you like, and include or leave out whatever you choose. I’m just really interested in learning about your experience.”

The young women’s accounts were unique and rich in detail. The timing of first being taken into care varied significantly across participants – from birth to age fifteen (although most entered the care system for the first time between the ages of nine and thirteen). While two of the women had remained with the same extended family unit while in care (both involving kinship care), the other eight had faced much greater instability through impermanent care arrangements. Only one of the participants had returned for any significant length of time to a biological parent’s custody. Seven of the ten young women had utilized post-guardianship / extended care agreements.

Across all participants’ interviews, the women made clear that they could not adequately articulate their journeys of coming to live well following their time in care without first describing their experiences that led them to enter the care system. Thus, each interview involved accounts spanning participants’ experiences before, during, and after their time spent in care, and beyond into their current lives navigating the world as young adults. These were difficult stories for women to share about their lives, and they were difficult stories to hear. And not surprisingly, participants did not describe an easy or straightforward path to living well. Their accounts highlighted varied and significant efforts to achieve a better life in a process that had continued over years. Indeed, each woman framed “living well” not as an endpoint but as an evolving experience as they continued to grow and thrive.

After the research team’s completion and transcription of all interviews, and their execution of preliminary analysis utilizing qualitative research methods informed by feminist theory, participants were invited to meet again with Sue to review early interpretations and to offer their feedback before the team finalized their analyses. At the conclusion of this rigorous process, Sue and the team began to present their research results at public forums.

Despite convincing research findings, Sue was dissatisfied with the project’s outcome. The compelling, complex, and moving nature of the women’s accounts, and the learnings that could be gleaned from them, had been muted by the scientific process, thematic summary, and the flattening of the flesh-and-bone messiness of lived experience into the tidy articulation of a scholarly report. Sue’s discontent with the traditional means of disseminating research findings became a catalyst for our creative collaboration.