Читать книгу My Maasai Life - Robin Wiszowaty - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление4

Finding my way

Suddenly everything had changed. For so long I’d yearned to break free, to let loose that inner fire and seek out a new life. I’d thrown myself headfirst into an entirely new world, not knowing what to expect. Fleeing Schaumburg meant seeking freedom, hoping for something more meaningful, more real. My Maasai life was unlike anything I could have imagined.

That first night I lay awake all night on the narrow bed Faith and I shared, struggling to get comfortable. I turned over and over, the wooden frame digging into my lower back and my skirt sticking to the thin, foam mattress. I felt in bondage by my clothes, by the night’s silence, by the uncomfortable bed.

Then a bone-chilling, high-pitched howl rang outside.

“Faith! ” I whispered.

“Naserian . . . ?”

“What is that sound?”

Faith rolled over, annoyed at being woken. “Hyenas.”

Hyenas? Now sleep was even more impossible. I tried to block out those echoing wails, but my mind flooded with questions. Was I doing the right thing? Was I just substituting one set of frustrations for another? Had I made a terrible mistake?

I winced at the thought of my parents seeing me filled with doubt or letting anyone see my apprehension. Dad, you want me to be fearless? Powerful? Determined? Unstoppable? They wanted me to be strong. I’d show them how strong I could be.

The next day I woke at the crack of dawn to voices and clatter coming from the kitchen. Stepping out from the manyatta, I stretched my arms and breathed deeply in the fresh morning air. The clouds hovered just over the hills’ grassy peaks under a wide overcast sky. I felt light years from the congested freeways and glittering shopping plazas at home. Despite restless sleep, I felt ready for the day to come.

I was jarred from my reverie by Mama’s shrill calls.

“Naserian! Tuende! ” Let’s go!

Back home, our family set aside Tuesdays for housecleaning, and I would inevitably gripe about having to do the dusting and vacuuming. Or throughout the week, when my parents asked me to clean my bedroom or wash dishes after dinner, it felt like a punishment, a little thing that felt like a life sentence. I’d whine and delay, thinking I had better things to do than help maintain our household. In my journal, I’d written, I will never settle for staying at home, cleaning up after my husband and children. Please let me never live that life, centred around daily chores, maintaining the status quo.

But it was quickly becoming obvious that my days in Nkoyet-naiborr would be defined by the many chores needed to maintain the boma, or household. Many of these were the same chores done for the upkeep of a North American home . . . but in a very different way. We still washed dishes and clothes, cooked meals, shopped for necessary supplies. But here, these daily duties weren’t just to keep the place spic and span. Here, they were necessary for our very survival.

The day’s first task was collecting water. In recent years, Western missionaries visiting the area had introduced piping projects throughout many areas of rural Kenya, allowing more families across the land to enjoy greater access to water. Our boma’s water was piped in from a natural spring up in the Ol Doinyo Hills down to a large metal storage tank about a kilometre from our home, next to the red-brick community schoolhouse where my brothers and sisters attended classes. Mamas from all across the community trekked there several times daily to collect water for their household purposes, from laundry to bathing to cooking ugali—a starchy, inexpensive cornmeal staple food for much of Africa.

As Mama explained, recent weeks had been dry, and water was scarce. It was the parched “white grass” of the prairies that gave Nkoyet-naiborr its name. During spells of drought that lasted anywhere between a couple of months to a couple of years, the daily water levels in the metal storage tank would be so low, the water could only be tapped from the spring at night. With such scant supplies, everyone had to reduce their overall usage, even as low as only one mitungi a day. Generally people were diligent about their usage, but it required community-wide participation to ensure everyone received their fair share.

In these dry periods, tough choices arose: should you wash your hair or your clothes? Can you bathe using just a cup of water? Can you prepare enough ugali with such limited cooking water?

I could tell Mama was unsure whether I was up for the task. She looked at my well-fed body and my soft, unworked hands, clearly sceptical as to my ability to do hard work. But I insisted I could do it—I just needed to learn. With a shrug, she picked up two plastic mitungis made from recycled cooking oil containers and motioned for me to follow her to the water source.

I followed Mama to the end of our property, marked by the fence fashioned from the thorny branches of felled acacia trees. With the fence in place, she explained, our sparse grass could grow protected from the grazing of the neighbouring cows that occasionally wandered by. We crossed the main road of red pebbled dirt and headed down the curved, worn footpath, weaving through the growth of sage bushes.

Rounding a bend in the path, Mama paused to twist a branch off what she told me was an East African greenheart tree. She snapped it in two and handed half to me, then continued on. I followed her example, shaving the bark off the branches’ edges and placing it in my mouth to soften the phylum. After a few minutes, she showed me, their bristles could be spread out and used as a type of toothbrush.

As we came down the hill’s crest toward the water source, I heard the high-pitched chatter of women’s voices. My face flushed and my palms began to sweat. Until now, Mama had been my guide and protector, leading me through this unfamiliar experience. I wasn’t a child, and I didn’t want to be shielded or supervised through new experiences, yet a lump formed in my throat. Would I be accepted, or would the women band against me? Would they not all wink at one another and sneer at me as an outsider?

The women in their colourful shukas circled the tank, waiting to fill their mitungis. I followed close behind Mama as she joined the line, greeting the other women. Everyone knew her, and the mamas greeted one another as if they hadn’t seen each other in years, even though they each came here every day. Mama was probably the loudest of them all; she called each woman by name, asking about their families, their livestock, any news heard along the way. The water source was the community’s mass communication system.

The attention quickly shifted to me. Mama took the stage and began rattling off Swahili to her gathered audience of mamas. I didn’t understand these words of introduction but tried to smile politely. I took my cue to bow my head to those older than me, as I had done with the elders in the pickup truck the day before. As the women looked me up and down, I felt horribly self-conscious and awkward. Everyone’s laughing! Are they laughing at me? Am I ever going to fit in?

I tried to play along, following the flow without fully understanding what was going on. Occasional words leapt out from the flurry of conversation: Chicago. America. The mamas nodded, impressed by whatever Mama was telling them. I could see my concerns were unfounded; Mama clearly just wanted me to get to know my neighbours, and she wanted them to meet me. They weren’t mocking me but discussing how they could best welcome me into their community.

As I watched the women talk I began to understand a bit about gender dynamics in this society. From my time so far, I could see that as a woman—and particularly as a young, unmarried woman—I would be expected to assume a very specific role in the family and in the community as a whole. At home I was used to laughing freely when a friend made a witty observation, or when a silly situation arose, yet now I was witnessing a new way for women to behave.

Back at the boma I learned to follow Mama’s and Faith’s examples, as I had been told that acting publicly in a flippant, overly enthusiastic and open manner would be seen as the behaviour of a promiscuous, easy woman. I had to learn to tone down my actions—not to be submissive, necessarily, but always remain conscious of acting respectfully. Men were the centre of attention, while women were meant to keep conversation going while sitting in very careful poses. Women maintained a humble demeanour, always staying vigilant of the family’s needs.

Yet at the water source, with no men around, the women were free to behave much more openly. Fetching water is a woman’s task, and this place was the women’s domain. Here mamas could gossip, joke and enjoy the camaraderie of fellow mamas. They sat however they wanted, their usual composed postures now relaxed as they sat on their mitungis and waited their turn. They laughed uproariously with one another, and I laughed too—though, of course, I understood none of it.

Soon it was my turn. Transporting water, I saw from the women, is an art unto itself. The mitungi must be carefully balanced on two rocks beneath the spout and then held in place while the trickling water slowly fills it all the way to the top. And with water always in scarce supply, we could never afford to waste or spill a drop.

When the cylindrical twenty litre container was full, it weighed more than twenty kilos. I stood stalled, uncertain of what to do next.

“I will show you,” Mama said.

She attached a long, woven rope to the cylinder and wrapped the other end around it once, then twice, securing it in an intricate knot. She then placed the rope around her forehead and reached down to knot the other end to the cylinder, creating a type of sling. I watched with wonder as she hoisted this heavy load up onto her slender back, adjusting the rope at a precise spot just above her hairline, so as not to pull at the skin, and at an angle that avoided strain on her neck. With the water stable, she shifted her hips, stood and was ready to walk. Her effort was definitely impressive, and I was amazed to see that some mamas even looped a second can below the first so they could carry two heavy loads at a time.

Then it was my turn to give it a try. On my first attempt I tied the rope wrong and, misjudging the balance of the weight, I let the rope slip from my forehead. I sighed and dropped the cumbersome mitungi back on the ground. Mama watched patiently, offering to take over as I sweated and strained. But I was determined to do it on my own.

While in Nairobi, preparing for my year with the family, I’d learned how drought is a regular and troubling reality for Kenya. Since water is vital to all components of daily life—cooking, cleaning, bathing, keeping livestock and staying hydrated in this parched land—scarcity, common during the regular seasons, can utterly devastate the population. Even if a family is well-off enough to afford adequate supplies of ugali flour and other staples, without the water with which to cook, they can’t eat. Hunger then runs rampant. As Mama told me, in drought seasons one saw the fattest cows reduced to skin and bones. People’s faces grew sunken and their bodies became emaciated.

Maintaining water supplies remains a mama’s greatest responsibility and the most important duty she must perform, often from an early age as with Metengo. If I was going to prove myself capable of rising to the challenge, I would have to master this task. And quickly.

I took a deep breath and tried again. This time I took more care in preparing the knot and made sure to secure the rope on my forehead before rising. With Mama nearby I finally managed to level the weight and slowly stood fully upright. With the other mamas watching, I took one step, then another, and soon we were headed back up the pebbled footpath to the boma, carrying enough water for our entire family.

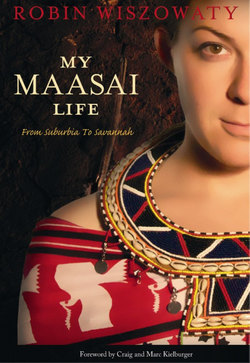

Faith and I return home after doing laundry—one of many household tasks for which, as a woman, I would be responsible.

In the rush of those first days I was introduced to so many new people that it was nearly impossible to keep them straight. Their names were all strange to my foreign ear, and at first all the kids’ faces looked the same to me. Yet my new family was eager to introduce me to their community and into their lives.

I found the social world in Nkoyet-naiborr was much more structured than average American life. There was an elaborate system of customs and rituals, maintaining a regimented social dynamic. Luckily, my adoptive family worked hard to help me understand.

Maasai conversations and greetings are conducted in a very specific manner, with certain codes of decorum and rhythms of speech. For example, as Faith taught me through broken English, Maasai greetings are always performed the same way.

First, one calls the name of the person being hailed: “Naserian!”

The response is then, “Ao! ” Yes!

In return, the person greeting the other answers, “Sopa! ” Hello!

And finally, the response: “Ipa!” Hello!

Conversation could then continue freely, but at a much slower, more methodical pace than I was used to. At home, it seemed people spoke rapidly, as if constantly afraid someone would cut them off; conversations often ran over one another, intersecting and colliding impulsively and quickly. Among the Maasai, individuals take turns speaking, while the listener encourages them along, expressing understanding with the repeated sound, “ay.” Rather than interrupting or finishing one another’s sentences, people strive to state facts and ideas plainly and thoroughly, taking turns.

This sense of decorum applied not only to adults, but also to the kids. As I’d already seen, people met their elders with the head lowered as a sign of respect. The elder then lightly touched the younger person on the forehead with a brush of fingers. Between Maasai men, a generous handshake was the custom.

As an outsider I wasn’t sure how I fit into this system. I was not a Maasai, so even though I was older than the children, the rules were different. The kids loved shaking hands with me, rather than being greeted with the touch to the head. They greeted me over and over: Naserian! Naserian! And every time I had to respond, Ao! Even as I grew tired of this game, they seemed to draw greater and greater pleasure from greeting me.

I loved being in this learning mode, especially in improving my limited grasp of Swahili. I was swept up in the experience; trying to learn the customs and daily rituals, while around me everyone spoke in an unfamiliar tongue, seemed overwhelming. I tried to remain unafraid to make mistakes. Here I was the new daughter of a new culture, and I was ready and willing to do my best to adapt.

But because my Swahili was so limited, and members of the family were themselves still in various stages of learning English, everything they said came out as a command.

“Go!”

“Come!”

“Naserian, bring! ”

I felt I was always being ordered, never asked politely as I was accustomed. Even Mama, whose English was relatively sophisticated, spoke mostly in these sharp directions. I’d be hard at work scrubbing dishes or performing some other task, then hear Mama calling out: Naserian! Naturally, I’d come hurrying in response, only to receive more commands.

“Give me that.”

“Get me the knife.”

Do this, do that: abrupt, functional exchanges always took the place of meaningful, relaxed conversation. The language barrier was just too vast. Yet this challenge only drove me to keep working at improving my Swahili and helping their English. I was sure that soon I would be able to join in on the laughter, the jokes, the sharing of intimate feelings.

After the sweaty slog back up to the boma, Mama and I dropped off our mitungis at the kitchen. Faith was already hard at work on preparing breakfast and, before I had a moment’s rest, Mama directed me to go help. Maintaining the family kitchen, including preparing meals, brewing tea, washing dishes and general cleaning, were also among a woman’s many duties.

I crouched and entered. Faith beckoned to me through the darkness and, as my eyes adjusted, I knelt next to where she was breaking up twigs, preparing them for kindling.

As Faith demonstrated, the basics of preparing the fire, used for cooking and boiling water. A metal pot, charred with years of use, was balanced on top of three rectangular stones, placed at square angles in a horseshoe shape. The space left open allowed firewood to be fed underneath to create a bed of blazing embers. We then broke up several handfuls of bark from a tall pile of dried branches and logs Faith and Mama had previously collected.

Faith arranged the kindling in a small tripod, placed larger branches on the outside and then took a can of paraffin wax from a shelf and coated the smallest kindling. Placing the paraffin back on the shelf, she reached for the box of wooden matches that sat next to it, and with a quick movement she struck one and touched its flame to the wax. Once the fire had caught long enough for the wood to smoke, she dropped to the ground and blew several times to fan the flame. The smoke grew thicker, and I turned my head to cough, squinting my smarting eyes.

Our kitchen stove—three rocks with room to insert firewood and a grill to hold a pot.

When the fire was generating enough heat, Faith placed another pot, filled to a third with water, atop it—water to be used for washing dishes from last night’s dinner. When the water began to steam, Faith removed it from the fire and placed it at her feet, dumping the dishes inside, along with the yellow bar of soap. A second pot was filled with a mixture of water and milk to boil for tea.

Maasai families typically only have chai tea with hot milk for breakfast, or occasionally fruit, if available, or on some occasions a small fried dough pastry called mundazi. Chai tea is a staple found in every Maasai pantry or kitchen, and brewing tea was considered another chore of great responsibility. It is considered essential to provide guests with tea, no matter the hour of day, and all Maasai—kids and adults alike—consider it an essential part of daily life.

Faith grabbed an unlabelled red container from the wooden shelf, unscrewed the yellow lid and poured loose tea leaves onto her hand to carefully assess the amount. Once the water and milk mixture had boiled she added the tea leaves and let the mixture boil some more. Faith then spooned in an equally diligently measured amount of sugar and sieved the completed tea into a plastic Thermos.

Just then the boys began to arrive for their breakfast tea.

“Naserian!” Saigilu, the eldest of the brothers, entered first, followed closely by Parsinte.

“Ao!”

“Sopa!”

“Ipa!”

With each family member’s entrance, our voices rang with greetings, and a fresh cup of tea was poured. Next came Morio, who giggled shyly at me, followed by Kipulel, who beamed proudly at greeting me in Swahili and his rudimentary English.

Then their father, Baba, who had returned from his travels late the previous night, entered the kitchen. Morio’s giggles came to a halt and everyone rose at once to greet him. He stood in the doorway, his head freshly shaven, wielding a long walking stick. He was clearly older than Mama, yet he had the slightly clumsy movements of a younger man. Though he was of average height and build, he possessed an aura of importance, and the children all met his greetings with hushed respect.

He and I hadn’t yet met, and I wasn’t sure what to expect or what he would think of me. I watched Faith to see how she responded. She bowed her head, as did my brothers, presenting the top of her head for him to touch.

Baba greeted me last.

“Naserian,“ he said in a deep, solemn voice.

“Ao? ” I replied. He placed his fingertips gently on my head, then gestured for me to lift my chin. He leaned in, his dark, probing eyes close to mine. I looked over at Mama and Faith, but they were busy scrubbing dishes, soaping cutlery and plates in one pot, rinsing in another.

“Sopa.” His eyes crinkled in a wide grin.

“Ipa . . . ?”

My voice was so quiet I barely heard myself, and Baba have me a quizzical look. I cleared my throat and tried again.

“Ipa! ” I shouted.

Baba laughed as my brothers scooted over, making room for him in the centre of the bench. Baba spoke loudly, his broad shoulders wrapped in two red shukas knotted around his shoulders, his chest dangling with beaded necklaces. The only non-traditional aspect of his appearance was the pair of jeans he wore under the shukas. The entire family was subdued and on their best behaviour in his presence. Mama poured a steaming cup of chai for him from the Thermos, reaching across the fire to hand it to him.

Mama was generally fairly protective about telling me about her past. She’d told me she had been born in Kuputei and came from a large family of farmers with three brothers and six sisters. She and Baba had been married for about nine years, and from the moment I met her I could see she was a dutiful, responsible mama and wife. I always tried to follow her lead when interacting with others in the community.

Seeing Mama and Faith’s dutiful demeanour in Baba’s presence, I felt myself also tighten up, even though he was eager to talk and ensure I was okay so far, and that I felt safe and secure in his home. Baba asked each of the children if they’d done all their schoolwork, then shared with us what had caused his late return last night: he’d visited neighbours whose cow had given birth, standing by in case his assistance was needed, and he’d helped another neighbour who was sick and needed to be escorted to a clinic in the market town. The entire family listened with admiration.

Soon Baba departed to check on the livestock, and the kitchen returned to its previous chatter. Faith snapped at Parsinte for almost knocking over her tea. Morio cried, complaining about not getting enough attention. Then Mama announced time was running out, so the kids hurried off to quickly wash up before their half-hour walk to school.

Kipulel lingered behind, and I asked if there was a problem. As if sharing a deep secret, he asked if there was enough tea left for a second cup. I laughed and poured him out the remainder of the Thermos. He chugged the hot liquid down in one gulp before running after the others.

As Faith and her brothers headed off for school, I settled in to finish the dishes, wishing them all goodbye in my best Swahili.

“Kwa heri! ” Goodbye!

“Haya!” Let’s go!

And off they went, excited for another day of school.

In the afternoon, Mama and I headed back out on foot. Though her days were typically occupied teaching at the elementary school, she’d freed time to show me around to all the community’s important sites: the school, the dam where the cows drank, churches, the health dispensary recently implanted by the government, many nearby bomas, the spot on the highway where we could catch a bus to the market town on our weekly visits. She indicated useful shortcuts and introduced me to many of our neighbours, who greeted me with laughter and enthusiasm. We followed long, meandering paths—to me they all appeared identical, but Mama navigated them as adeptly as I could Schaumberg’s winding crescents and avenues.

At each boma we were greeted with welcoming smiles and a fresh cup of tea. With hospitality and generosity toward guests at the cornerstone of Maasai culture, at each boma mamas and their families opened their homes to us, especially tickled at entertaining a guest from far away. No one thought twice about visitors dropping in for an impromptu visit, and they were always ready with a pot of tea, sometimes a plate of ugali at lunchtime.

News travelled fast in the close-knit community’s chain of gossip and word spread that a girl from America had arrived in Nkoyet-naiborr. Wherever we went, people knew who I was before I knew them, and they met me enthusiastically.

“Naserian!”

But after the customary greetings, they’d break into exuberant conversation, sharing the details and dramas of their lives, even though I had next to no clue what they were saying. So one of the first things I learned to say in Maa was mayiolo maa: “I don’t know Maa.” They seemed to find this absolutely hilarious.

After a number of these visits, I was jittery with cups and cups of strong tea and my stomach was full to bursting. Yet I had to keep graciously sipping, nodding to show my appreciation even as the cup grew cold. Once again, I reminded myself to keep an open mind and, more importantly, to keep hope in my heart.

In the days to come, I met an endless procession of Maasai neighbours. Guests showed up regularly at our boma, with the expectation that I’d greet and serve them, just as they’d done for me. Usually, however, Faith was one step ahead of me and already brewing tea by the time it occurred to me to begin serving. Again, all I could do was just try and fulfill my role, perform my chores, then sit quietly and fit in as best I could.

I was expected to know and recognize all the people I’d met. But there were so many: stranger after stranger came by, each speaking in a foreign tongue. There were so many names to remember, so many faces. Yet my family was adamant: How could you forget her name? You just met her yesterday! She’s the sister of the neighbour’s brother’s market lady’s . . . I pretended to keep it all straight. But I really couldn’t.

When guests left our boma, Mama and Baba would request that I walk them part-way back home. But I’d eventually get lost on the way back and usually ended up asking someone along the way for help. By accident, I learned my way around just by stumbling foolishly from one boma to another, helped along the way by friendly souls seeing this fish out of water scrambling to get home.

One time, after a late afternoon visit, I tried to lead a group of guests back to their home. After we’d said our goodbyes, I headed back in the direction I’d come, looking forward to relaxing after an exhausting day. Trudging home under the blazing sun, I was in somewhat of a daze and lost my way. Still getting used to meagre, basic meals and only tea for breakfast, along with a busy slate of daily tasks, I was left with little energy at the end of the day.

Then I stopped in my tracks. I was at the intersection of several footpaths, each stretching off into identical landscapes of rough brush and reddish dirt, well-worn by many feet. In my tired stupor I’d lost my bearings and had no idea which way to go. The sky was darkening, and dusk fell quickly here, and with dusk came hyenas. If there were hyenas, were there other animals, too? Like . . . lions?

I heard slow footsteps crunching in the dust behind me. I wheeled around to find a small Maasai man, draped in red, coming up behind me. Bracing himself with a walking stick, he muttered a few words I didn’t understand, except for one: Naserian. Apparently my reputation had already preceded me.

Sensing my confusion, he gestured with his walking stick in several directions, speaking in a low, calm tone. I still didn’t understand, but I caught the essence of what he was asking: Where are you trying to go?

I had no idea how to respond, except for a Swahili word I’d recently learned: nyumbani. Home.

He nodded, indicating understanding. My relief was inexpressible, and in my gratitude I momentarily forgot how tired I was. He led the way, down one of the several paths, and I followed closely behind. We continued at his slow pace as evening began to fall.

Night skies in Nkoyet-naiborr were a revelation of stars, a sweeping sky of twinkling constellations unlike those visible in the cities of America. While I gaped with amazement at the view overhead, my Maasai guide shuffled forward, leading me, and soon I recognized the trail that led to my boma. I thanked him profusely, but he simply continued on his way.

I knew Mama would be annoyed, and possibly concerned, at my late return. I was embarrassed that I’d gotten so lost so easily. But I was determined to feel my way forward on my own. After all, finding my own path was I’d come here to do. A little help along the way didn’t hurt.