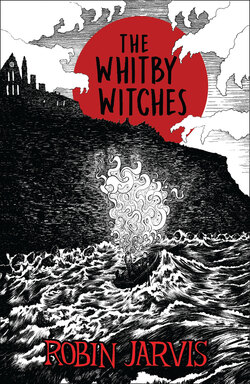

Читать книгу The Whitby Witches - Robin Jarvis - Страница 6

ОглавлениеI

DIFFICULT CASES

Mrs Rodice perched herself on the edge of her spartan desk and sucked her watery afternoon tea through sullen lips. She was relieved, for two of her more trying charges had left today – she had put them on the train personally. A delicious shudder ran down her spine as she sank her small, irregular teeth into a dunked digestive. This was her favourite part of the day – a special, secretive hour when she could close the door and relax with her Royal Doulton and occasional romantic novel.

Margaret Rodice ran a hostel for children, those whose parents were dead, indifferent or ‘inside’. It was a difficult, demanding role: trying to manage a maximum of sixteen young people while at the whim of the local authority grant policy. If only Mr Rodice had not departed from the world so shortly after their wedding. She wondered how different her life would have been; perhaps there would have been children of her own – even a grandchild by now.

Mrs Rodice rattled the cup on its saucer in agitation and placed them both on her desk. She really must stop dwelling on the past. Donald was a vague shadow from her youth and she rarely thought of him now – up until recently, that is. But now that creepy little boy had gone and she hoped things would get back to normal. Oh, for the run-of-the-mill occurrences: the runaways, the girls who pinched, even (God forbid) nits would be welcome after the turmoil of the last three months.

She rose to peer out of the narrow window and watched the rain streak down over Leeds. After some minutes of contemplating, Mrs Rodice returned to her desk, but refrained from draining her cup. The tea leaves at the bottom would only remind her of the recent troubles.

‘Of course I was right to send that letter,’ she reassured herself. ‘Even if the old bat does know someone on the board, she had to be aware of what she was letting herself in for.’ Mrs Rodice shook her head at the folly of the old woman in question.

‘At her age! I ask you,’ she addressed the table lamp. ‘Well, it won’t last – it never does with them.’ A thin smile twitched her mouth. ‘Still,’ she muttered, shuffling her papers, ‘whatever happens, they’re not coming back here.’

She bent her greying head over the spread of forms and took up her pen purposefully, then with a tut of consternation looked up at the ceiling and groaned. ‘I hope Yvonne won’t wet again tonight.’

Ben stared out of the window and watched the green landscape race by. He pressed his face against the glass and the motion of the train vibrated through his nose.

‘Don’t do that,’ sighed the girl beside him, as she pulled him back to his seat.

The boy squirmed and plucked crumbs of sausage roll from his sweater. ‘Bored, Jen,’ he grumbled.

Jennet fished a comic out of a large blue canvas bag beside her and shoved it under her brother’s nose.

‘I’ve read it,’ he said, without bothering to look.

The girl let the comic sprawl on the table and turned away. Ben’s eyes flickered over the colourful pages. He pursed his mouth with his usual show of contempt and returned his attention to the window. A curtain of silence and resentment fell between the children.

The train slowed and pulled into Middlesborough. Ben twisted on his seat, his eyes following the people who got off. He was eight years old, a serious-looking boy with mousy hair and eyes which were set unusually deep below his frowning brows. His sister, Jennet, had the same oval face and unremarkable, blobby nose, but her long waving hair was darker and her eyes were less troubled.

The guard strode by, slamming the doors of the carriages, and Ben kicked the seat impatiently with his heels. Jennet said nothing but looked at him disapprovingly. Ben considered himself scolded and the kicks subsided.

‘We nearly there?’ he asked suddenly.

‘I don’t think it’s far now,’ she answered.

Ben abandoned the delights of the window and faced his sister. With one of his disconcerting stares, he asked her soberly, ‘Jen, what do you think it will be like this time? Will we be there long?’

The girl shrugged. ‘Miss Boston’s old, that’s all I could get out of the Rodice.’

At the mention of that name Ben screwed up his face. ‘I hated her,’ he said passionately. ‘I’m glad we’re not there now. She used to frighten me.’

‘Not as much as you frightened her,’ remarked his sister dryly. ‘Listen, remember what I said.’ A warning note crept into her voice. ‘You’re not to talk of that with this one, right?’

Ben nodded and hastened to change the subject. ‘Will we really live near the sea, Jen?’

‘Yes, I think I heard Rodice say Whitby was on the coast – it’s the end of the line, anyway.’

‘And did Peter Pan live there too?’

Jennet picked up his discarded comic and flicked through it herself. ‘Peter Pan?’ she asked, puzzled.

‘Yes. Mr Glennister who put them flags down last week told me Captain Hook came from there.’

‘He must have been pulling your leg, then,’ said Jennet flatly.

‘Oh.’ Ben was deflated and slouched back. ‘Didn’t like them flags anyway,’ he mumbled. ‘There’s no grass left now.’

‘Rodice said it would be cheaper in the long run,’ said Jennet distractedly. Then she raised her head and, imitating Mrs Rodice’s humourless nasal tones, added, ‘Grass needs regular mowing in the summer and in the winter the passages are covered in mud.’

Ben chuckled; he approved of anything that made fun of the dreaded Rodice. He rubbed his eyes, then asked, ‘Don’t you know anything else about this place?’

But Jennet was trying to concentrate on the comic, and ignored him. A year – perhaps eight months – before she would have been nervous and excited at the prospect of moving to somewhere new. She might even have looked the place up in the library to learn something about it beforehand. But that was four different foster homes ago.

‘I think I’ll like the sea,’ continued Ben. ‘Have I been to the seaside before, Jen?’

‘When you were five.’

‘Were they there too?’

She coughed and stared at the comic intently. ‘Yes,’ she replied curtly.

Ben frowned and put on his most serious face. ‘What I mean is . . .’ he struggled to choose the right words, ‘were they really there?’

Jennet threw the comic down and snapped sharply, ‘You’ve seen that photo of us, haven’t you?’

Ben’s eyes grew large and pleading. ‘Not for a long time, Jen – you won’t show me the photos any more. Couldn’t I see just one of them now?’

‘No, they’re at the bottom of the bag. Besides, you don’t need to see photos of Mum and Dad, do you?’ It was an accusation, spat out bitterly. She folded her arms crossly and stared down the carriage at a toddler sleeping in his mother’s arms. Ben began to kick the seat again and rested his head sulkily on the window.

Jennet was tense. In the past they had always met the foster families before going to stay with them, but this time everything was different and rushed. Mrs Rodice was probably only too glad to get them off her hands and no doubt had hurried the procedures along. Still, it was very odd. The first Jennet had heard of this Miss Boston was two weeks ago, but presumably negotiations had been going on long before that. Jennet was curious. Why would an old woman go out of her way to foster two children she had never even seen, and why would the authorities let her? If only the Rodice had said more. But then Jennet had not bothered to probe into the matter very deeply. She and Ben had never had much say about where they were shunted off to, and now that they were categorised as ‘difficult cases’ they had none at all.

Jennet was now beginning to regret her lack of interest. Miss Boston seemed such a mysterious figure. All she knew about her was that she was old. Would Miss Boston be there in person to meet them at Whitby station, she wondered, and just how old was she?

Jennet allowed a smirk to spread over her face; perhaps some wizened hag in a bath chair would be waiting for them. A new thought struck her: maybe the old lady had money. That would explain the haste with which their fostering had gone through the system. The bath chair vanished abruptly from beneath the imaginary figure and was replaced by an ancient Rolls Royce, with a chauffeur in grey livery holding open the door. Inside was the same old woman, now swathed in furs, her wrinkled hands dripping with diamonds.

If money was involved Jennet wondered whether she would be sent to a posh school. That’s what rich people did with children. It was an unwelcome thought and she mulled it over miserably. She and Ben had not been separated since the accident. Jennet could not imagine life without her brother, however much trouble he caused.

The stations the train stopped at were becoming smaller, their names spelled out in whitewashed stones on well-mown slopes. Some even had hanging baskets dangling from the eaves. It was like taking a journey back to the age of steam and Jennet half-listened for the ‘chuff chuff ’ she had heard in old films.

The scenery was beautiful. Wild expanses of rolling moorland dotted with sheep shot by, then a dense pine forest, some farm buildings with a gypsy caravan parked outside, and then more wide acres of heather, cut through by a little brook.

The railway track became a single line. Just how far away was Whitby? It seemed as if they were going beyond the reaches of the civilised world. Jennet wondered how regularly the trains went there and wished she had thought to look at a timetable when they had changed at Darlington.

‘Look,’ said Ben excitedly, ‘there’s a river and there’s a boat, see!’

A ribbon of water ran parallel to the track. For some moments it was obscured by dense trees, then was revealed once more, wider than before. Buildings clustered on the far bank and the river swelled into a marina, with yachts. Jennet caught a glimpse of a high cliff, then the vision was snatched from view and the train, wheezing with exhaustion, finally drew into Whitby station.

‘I saw the sea,’ declared Ben, jumping up and down on the seat. ‘And there were lots of fishing boats. Listen to the seagulls, Jen.’

She grunted an acknowledgement and stuffed the wreckage of the journey into her large blue bag. She left the empty can of lemonade and two brown apple cores on the table and told Ben to put his coat on.

‘But it isn’t cold,’ he protested obstinately.

‘Put it on,’ she insisted.

Ben mumbled a sentence, but the only word Jennet could catch was ‘bossy’. When he had fastened the top button of his coat, she guided him in front of her and swung the heavy bag over her shoulder.

There were only a few other passengers on the train; they filed past the children with neat little suitcases and hold-alls, smiling as they gave their tickets to the man at the barrier. Ben stared at the sky. The rain had left behind a bright August day with big white clouds rolling inland. The seagulls circled high above and cried raucously.

‘I can’t see anyone,’ said Jennet, looking up the platform. ‘Come on, maybe she’s waiting for us outside in her car.’

They trudged up to the barrier and Jennet began to rummage in her pockets for the tickets. The ticket collector cast a weary glance their way and held his hand out impatiently. Ben stared up at him and pretended to pick his nose. The man set his jaw and glared down icily. Jennet, meanwhile, was still rifling through her pockets.

‘Come on now, miss,’ said the man.

Jennet was flustered; she could not think what had happened to the tickets.

‘Has it arrived, George?’ came a brisk female voice.

The ticket collector turned and nodded to the newcomer. ‘Aye, an’ three minutes early, Miss Boston.’

Jennet looked up sharply. There, with her hands clasped firmly behind her back, stood a stout, white-haired woman. She wore a jacket of sage-green tweed with a matching skirt, and on her head sat a shapeless velvet hat. The cobweb lines around her grey, bird-like eyes suggested the old lady’s age to be about seventy but her stance was like someone much younger.

‘Ah, three minutes, is that so?’ Miss Boston spoke challengingly and raised her eyebrows at the ticket collector. ‘Well, well, what a day for wonders, to be sure.’

Then the old woman saw the children and her face lit up. The eyes blinked and disappeared and the rolls of skin beneath the chin shook like jelly. ‘Oh, these must be mine,’ she cried, clapping her hands together like an eager child.

‘Yours, Miss Boston?’ asked the ticket collector, baffled.

‘Yes, yes, George. Now let them through that wretched thing.’

‘But they an’t give me their tickets.’

‘Oh stuff !’ she exclaimed in exasperation. ‘Let them through at once, they’re with me.’ And she stamped her foot and gave the man a look which no one would have dared to disobey.

‘This is most irreg’lar,’ he said as the children squeezed past him, ‘most irreg’lar.’

Miss Boston clucked gleefully as she ran her keen eyes over Jennet and Ben. ‘Let me have a good look at you,’ she demanded. ‘So, you’re Jennet.’

‘Yes,’ the girl replied, returning the interested stare.

‘Pretty name – far better than Janet or Jeanette. Now I believe you are twelve, is that correct?’

‘Yes.’

‘Mmm. You look older – act it too. Not surprising, really.’ Miss Boston nodded as though satisfied with the girl and turned her attention to the boy.

‘And this is Benjamin, I presume.’ It was a statement rather than a question.

The child stared back and said nothing.

‘He’s shy with strangers,’ put in Jennet.

‘Of course he is,’ the woman returned. ‘All sensitive children are timid.’

‘Ben’s not sensitive, just shy,’ corrected Jennet firmly.

‘Ah, yes – you must forgive me.’ Miss Boston’s face looked like someone guiltily sucking a boiled sweet. ‘Well,’ she went on, ‘I trust I shan’t be considered a stranger for very much longer – by either of you.’ Her smile was warm and genuine. ‘Now, come,’ she cried, waving them out of the station, ‘let us retire to my home and have a bite to eat before you unpack.’

As they left the station Jennet saw for the first time the town of Whitby. The girl stood stock still and absorbed the sight breathlessly. The station was close to the quayside and the harbour was filled with fishing boats, from large fat vessels with wide hulls and tall radio masts down to the simplest coble, painted red and white. Close by there was a long red boat which ran fishing trips for the tourists.

On the far side of the harbour was a jumble of buildings with roofs of terracotta tiles, nestling snugly alongside each other like a queue of nervous bathers waiting for someone to take the first leap into the water. They were built on a steep cliffside and the hotch-potch of sandstone and whitewash somehow seemed to be a natural feature of the landscape. They felt right, as though they had been there from earliest times and without them the land would be naked and ugly.

Jennet’s eyes scanned up beyond the houses, to where the high plain of the cliff reached out to the sea. She gasped and stared. For there, surmounting everything, was a ragged crown of grey stone – the abbey.

The building was in ruins, but that did not diminish its power. The abbey had dominated Whitby for centuries and waves of invisible force flowed down from it. The ruin was a guardian, watching and waiting, caring for the little town that huddled beneath the cliff. It was a worshipful thing.

Miss Boston nodded. ‘Yes,’ she sighed dreamily, ‘the abbey. It is indeed lovely. There has been a church on that site for at least fourteen hundred years. One gets a marvellous sense of permanence, living under such an enduring symbol of faith. If one believes in the genius loci – the spirit of place – then surely therein dwells something divine. The Vikings came, Henry did his best to destroy the abbey with the Dissolution of the Monasteries and in the Great War German ships bombarded it. Yet still it stands – stubborn and wonderful. They say a true inhabitant of Whitby is lost if he cannot see the abbey.’ She paused and looked at the ground. ‘Well,’ she went on again breezily, ‘there I go, off at tangents again. You two may have eaten but I have not. Come, tea awaits.’

Jennet dragged her eyes from the cliff and glanced about the road. ‘Where’s your car?’ she asked curiously.

Miss Boston puffed herself up indignantly. ‘A car?’ she cried, her chins wobbling. ‘I don’t need a car. Whitby is not big enough to warrant the use of an automobile, child. However, I do have transport, now you mention it.’ She strode round to where an old black bicycle was leaning against the station wall.

Jennet bit her lip to stop herself cracking up with laughter at the thought of the old woman riding round on that. Had she and Ben come to stay with the local nutter?

Miss Boston announced that she would not ride but walk, for the sake of the children. ‘Now, this way,’ she declared, setting off. The bicycle clattered and whirred beside her.

Ben had been silent since they had met but by now he had decided that the old woman was harmless and much friendlier than the Rodice. There were none of those phoney smiles and patronising looks which were a feature of the Rodice’s way with children. He was also relieved that this adult had not tried to pat him on the head or ruffle his hair, like some others had done.

Now his excited eyes saw the fishing boats with their gleaming paintwork, orange nets and lobster pots. A twinge of pleasure tugged at his insides when he thought of actually sailing in one of them. It was not impossible. If the old woman liked him and Jennet and if he kept quiet about certain things, they might stay here just long enough.

Ben was already beginning to find Whitby a thrilling place, full of possibilities. Suddenly he remembered again what Mr Glennister had told him. As he walked behind his sister along the New Quay Road a determined expression crossed his face and, forgetting his bashfulness, he pulled at the old woman’s sleeve.

‘Where’s Peter Pan?’ he demanded.

Miss Boston stopped and blinked. ‘Whatever does the dear boy mean?’ she asked Jennet in surprise.

‘He was told Captain Hook lived here,’ explained the girl in an apologetic tone.

Miss Boston hooted loudly and frightened some gulls on the quayside. ‘Bless me, Benjamin,’ she chuckled, ‘it’s Cook, not Hook. Captain Cook lived here.’

‘Oh,’ murmured Ben. He felt babyish and all the shyness returned in a great flood. He waited for the old woman to call him stupid, but instead she said something quite unexpected.

‘Peter Pan, eh?’ Miss Boston mused to herself. ‘Do you know, young man, you have crystallised something I have felt without realising. For some time I have sensed that there is, oh how shall I say? something special about this place of ours. It almost seems to have been neglected by time. Oh yes, we have motor cars passing through and amusement arcades on the West Cliff, which scream of the twentieth century, plus of course the summer visitors snapping their cameras, yet . . . there is an aspect of the town which belongs to the past. Never-Never Land is a good comparison . . . yes, most interesting. How perceptive you are.’

She wheeled her bicycle on once more. Ben looked up at Jennet, who gave him a frosty stare.

‘Just don’t be too perceptive,’ she whispered harshly.

‘Captain James Cook was a very famous mariner,’ Miss Boston called to them over her shoulder. ‘He lived for some time in Grape Lane on the East Cliff – we shall pass by there on the way to my cottage. He discovered Australia, you know. Still, we must not hold that against the man.’

They came to a bridge spanning the river. It was only wide enough to take one line of traffic at a time and was jammed with pedestrians, swarming everywhere.

‘Our busiest time of year,’ Miss Boston explained as she ploughed her way through. ‘We’ve just got over our regatta and the folk week starts in two days.’

‘Folk week?’ queried Jennet.

‘Yes, with lots of morris dancing – people come from miles. The town is always packed with bearded men who black their faces and walk about in clogs – such fun.’

When they were halfway across the bridge, Ben glanced back. The road they had left was just beginning to get interesting. He heard the crackle of electronic guns and the amplified voice of the bingo caller. A row of glittering arcades stretched out towards the sea beneath another cliff.

‘That is the West Cliff,’ said Miss Boston as she negotiated her way through a crowd of giggling girls. ‘Traditionally the East Cliff was for the fishermen and the West for the holidaymakers. Of course it’s got a little mixed up over the years; most of the fishermen can’t afford to live here any more so they have to travel in.’

They reached the far side of the river. ‘Down there is Grape Lane,’ indicated Miss Boston, waving her hand.

The buildings of the East Cliff were more densely bunched together than Jennet had at first thought. They had been built in the days before planning permission was heard of and their higgledy-piggledy clusters formed a vast number of dark alleys, lanes and yards. The Whitby of the East Cliff was gazing at the world from an earlier time all its own.

Miss Boston led them up a narrow cobbled road called Church Street. It was the main thoroughfare of the East Cliff, yet still cars had difficulty making their way down it. Old buildings hunched over on either side in a forbidding manner and tiny lanes led off through sudden openings to unseen doorways.

‘Afternoon, Alice.’ A thin, elderly woman greeted Miss Boston courteously. She had the palest blue eyes that Jennet had ever seen and her silvery hair was scraped tightly over her head, to be bound in a fist-sized bun at the back. She wore a grey cardigan over a lemon yellow blouse, fastened at the neck by a cameo brooch, and clasped a brown handbag primly in front of her.

‘Oh, Prudence,’ returned Miss Boston hastily. ‘Did you manage to come across that book?’

The other shook her head and sniffed. ‘Sorry, Alice – must have thrown it out with Howard’s things after all. Never kept much of his stuff you know.’ Her voice was clipped and precise. Then she regarded the children and waited for an explanation.

‘My guests, Prudence: Jennet and Benjamin.’

‘Yes, well. They’re younger than I thought. I hope you know what you’re doing.’ She then continued the conversation, ignoring the children completely. ‘Actually, Alice, I have just come from your cottage. That Gregson woman told me you were not at home.’ She shook herself and adjusted the cameo. ‘So I was about to take myself off to call on Tilly. Haven’t seen her for over a week – more kittens I imagine. It’s all getting too ridiculous. Well, must cut along. Goodbye.’ And with that, she walked briskly away.

‘Don’t forget Sunday,’ Miss Boston called after her.

Without slowing her brisk stride the woman raised her hand dismissively and called back, ‘Naturally.’ Then she was lost in the crowds.

Miss Boston turned back to the children and sucked her breath in sharply. ‘That was Mrs Joyster,’ she informed them. ‘Rather a cold woman, I’m afraid – husband was army and it rubbed off on her. Sometimes I feel as though I’m being drilled when she talks to me. Mind you,’ she added, ‘she can be very pleasant at times.’

The bicycle began to clatter once more. ‘I recall how I used to hate it when adults pretended I wasn’t there; dear me, that was a long time ago now. Do you prefer blackberry or raspberry jam? I confess I have a passion for both – especially on hot scones. My cottage is not far now.’

Jennet and Ben were beginning to find Miss Boston’s abrupt changes of thought bewildering. It did, however, occur to them that they would have no difficulty polishing off a plate of jammy scones.

An odd, square building on the left caught their attention. It was set a little apart for one thing. Pillars supported the upper storey and right at the top, in the middle of the roof, was a clock tower and a weather vane shaped like a fish.

‘This is Market Place,’ said Miss Boston, waving a proud hand. ‘If you’re keen, you could go on this.’ She pointed to a black sign with white letters advertising a Ghost Tour.

Ben’s eyes widened and he swallowed nervously. The sign drew him like a powerful magnet. Jennet pulled him roughly away as if from a fire.

‘No!’ she told the old woman. ‘We don’t like that sort of thing at all.’

If Miss Boston was surprised by the severity of Jennet’s outburst then she did not show it. ‘Really, dear?’ she said mildly. ‘Then I’m afraid you have come to the wrong place entirely. You know I sometimes think Whitby has more ghosts than living residents.’ She waggled her chins at the sign and muttered. ‘Just as well, really – I’ve been banned from going on the tours anyway. Well, the young man who runs them seemed to resent my chipping in. Got quite irate once when I corrected him. He gave me my money back on the proviso I never bothered him again. Astounding state of affairs.’

They had come to another of those sudden openings and Miss Boston wheeled her bicycle through it. After about five metres the alley opened out into a spacious yard. She walked up to a flight of steps, rested her bicycle against a rail, opened a green door and said, ‘Well, come in then.’

Jennet was downstairs, talking to Miss Boston. Ben lay on an embroidered quilt and stared at the primroses in the wallpaper. It was a small room but just big enough for him, and for a change, he had it all to himself. There was a bed, a chest of drawers next to it with a lamp on top and a small wardrobe. He licked the jam from his chin and rolled over to gaze at the sloping ceiling.

It was a funny house. There were lots of weird prints on the walls and old sepia photographs of Victorian Whitby. There were also a good many corn dollies hanging up all over the place. A table in the hall was reserved for things Miss Boston had found while out walking: pine cones, bright orange rosehips, a bunch of heather, sheep’s wool found in a hedge, complete with twigs and fragments of leaf, the broken shell of a blackbird’s egg, several interesting pebbles, a gnarled piece of driftwood and a white gull’s feather.

This was not what he or Jennet had expected, and it certainly disproved the idea that Miss Boston was rich – unless she kept a secret stash of tenners under the mattress. It was not the sort of house you would expect an old lady to live in, whether she was rich or not. There were no china shepherdesses or rows of dainty cups, no bits of fussy lace, no piles of women’s magazines heaped in the corner, no obvious signs of knitting, no fat lazy cat sprawled on the sofa clawing away at the cushions and – best of all to Ben – the place did not smell of lavender. He thought he would like it here. Miss Boston was not the average old lady; there was something vital and a little bit eccentric about her.

An idea came to him as he lolled on the bed. Gingerly, he crept out of his room and went into Jennet’s. He could still hear the faint hum of voices downstairs so he knew he was safe.

Ben fumbled with the zip on the blue canvas bag and delved through piles of neatly folded clothes and small treasures. There, right at the bottom, his groping fingers touched what felt like a book. Gently, he slid the photograph album out of the bag and stroked it lovingly with his hands. With great care and reverence he opened it and turned the pages. This was a hallowed thing to him and Jennet and lately she had been withholding it from him.

There were his mother and father on their wedding day, smiling up out of the album, about to cut the cake. Another page and there they were on honeymoon in Wales. Ben’s father was a tall man with thick, dark hair and a broad grin. His mother, a petite blonde, had blinked at the wrong moment, and here she was, frozen into an eternal doze. The opposite page showed Jennet when she was a baby, sitting on her father’s lap.

Ben examined the photographs carefully. Here they were: images of his parents locked in happy events – birthdays and holidays sealed into the album forever. But the eyes staring out at him were unseeing. They were focused on the person taking the photograph and that had never been Ben. His mother and father were looking out at someone else, not him. He was confused. The memories of who they had been – everything they were – were now transferred to six inches by four of glossy paper.

He turned the last page. There was the photograph he sought above all. A younger version of himself sat astride a donkey on the sands of Rhyl and beside him were his mother and father. Jennet must have taken the picture. Try as he might, Ben had no memory of the occasion. He imagined sitting on a donkey and hearing his father’s voice, but no – there was nothing there. The photograph had been taken on the final day of their last holiday together. Six months later both his parents had been killed in a car accident.

Ben closed the album, then frowned and chewed his lip. He understood that his parents were dead. He and Jennet had gone to the funeral and watched the coffins lowered into that deep hole. He remembered that because he had worn those shoes that pinched and Jennet had cried a lot and had to be put to bed. Yes, his parents were dead; everyone told him that. So why was it that every now and then, in a mirror or at the end of his bed before he went to sleep, he could see his mother and father smiling at him?