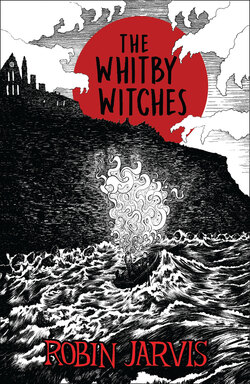

Читать книгу The Whitby Witches - Robin Jarvis - Страница 8

ОглавлениеIII

THE LADIES’ CIRCLE

Ben turned the ammonite over in his fingers and stared intently at it. It was the same size as a fifty-pence piece and charcoal in colour. Miss Boston had told him that it was incredibly old, older than the human race, in fact. Ben held it tightly. It felt safe to touch something so ancient – there was very little permanence in his turbulent life and this small, time-polished fossil was like a magic talisman, a sign that perhaps things would be different from now on.

It was late and the three of them were sitting in the parlour. The curtains were drawn and Aunt Alice had lit a fire as the night had grown chill. Now the children lounged on the wide sofa and sipped hot chocolate.

Jennet looked across at the old lady, whose face glowed in the flickering firelight.

‘Shall I tell you the legend of the ammonites and St Hilda?’ Aunt Alice asked them.

Ben pushed himself further into the cushions and nodded.

The old lady gazed into the fire and began. ‘In the olden times, when Caedmon was alive, the Abbess of Whitby was the niece of a great northern king. They were dark, severe days and most of the people were still pagan, worshipping cruel gods on the moors and at the river mouth.’

Her quiet voice lulled Jennet’s senses and she began to drift far away. The old lady’s words conjured up vivid pictures and she shivered, imagining the horrible things that must have happened in those savage times.

‘Well,’ continued Aunt Alice, after she had drained her mug, ‘it is said that the cliff-top where the abbey now stands was alive with snakes. They were such a nuisance that the Lady Hilda took up a whip or staff and drove them all into the sea where, by her prayers, they were turned to stone. However, the three largest serpents had escaped her anger, and they rose out of the grass to strike her. Furiously, she hit out first and cut their heads clean off, while their bodies sailed through the air and were embedded in the wall of a house at the bottom of the hundred and ninety-nine steps. They are still there to this day, if you care to look.’

Ben groaned – yet another soppy story. He liked the bit about the snakes, though. He examined his fossil once again and hissed softly to it.

Jennet stirred a little but still gazed at the flames through narrowed eyes. ‘Is any of that true?’ she asked. ‘I mean was Hilda really the niece of a king?’

‘Oh yes,’ Aunt Alice assured her earnestly. ‘Edwin of Northumbria was her uncle, though some say father. She was a princess, in any case. Word got around that one of royal blood was coming to Whitby and gossip confused the true facts – rather like Chinese whispers, I imagine. Eventually half the population believed Hilda was a great sorceress, but we actually know very little about the real woman. The story of the snakes is obviously allegorical, the serpents representing the pagan religion which Hilda overcame. Still, it is a quaint tale.

‘Now I think it is time for you both to go to bed. You’ve had a busy day and so have I, what with troublesome cats and barmy old Tilly.’

Jennet dragged Ben from the cushion cave he had made for himself and his pet snake. Hissing like a puncture, the boy ran up the stairs. His sister followed behind him and turned to Aunt Alice, who was carrying the three empty mugs into the kitchen. ‘Did you go to the estate agent’s?’ she called down sleepily.

‘Indeed I did,’ answered the old lady, raising her voice above the sound of the running tap as she rinsed the cocoa dregs away. ‘The house is not going to be knocked down. A woman has bought it. They weren’t going to tell me but I know the mother of the young man behind the desk. He told me a Mrs Cooper had purchased the place. Has ideas of turning it into an antiques shop – ridiculous notion. We have far too many of those already and the house is too far off the beaten track to make it worthwhile.’

Miss Boston emerged from the kitchen and smiled up at Jennet. ‘Well, goodnight, dear,’ she said.

The next day was Saturday and the beginning of the folk week. Early in the morning the two children raced round the West Cliff, looking at the odd assortment of people who were turning up. They spent an interesting half hour watching cars and vans squeeze through the town while they tried to guess what sort of people were inside.

There were morris dancers, a whole gaggle of bagpipes, long-haired hippies with guitars and peace stickers, a fleet of flutes and penny whistles, a group of mummers dressed in the most outlandish costumes Ben had ever seen, and even two belly-dancers.

Whitby was heaving with people. Jennet laughed as she realised how true Aunt Alice’s words had been – there were a lot of bearded men and they all seemed to have the same sort of clothes on. It was like some kind of uniform: a good thick jumper with a clean white shirt underneath, then brown corduroy trousers and, for the really serious, the ultimate accessory was a pewter tankard, attached to the belt.

A jolly, fat lady with cheeks like two beetroots clambered, with difficulty, out of a beaten-up old Mini. Then she leant in once more and hauled out an accordion as big as a coffee table. She beamed at the children as she passed by. Ben stared after her eagerly. This really was the most extraordinary place he had ever been – something always seemed to be happening.

The morning shadows dwindled and lunchtime drew near. Ben’s stomach growled and he reluctantly agreed with his sister to head back home. The town was seething, its streets thick with enthusiasts, musicians, tourists, and the poor locals trying to do their Saturday shopping. It took an incredibly long time to reach the bridge and crossing that was another Herculean task.

Jennet sighed with relief as the narrow streets of the East Cliff closed round her, but even here the crowds were phenomenal. She gripped Ben’s hand tightly in case he was washed away on the tourist tide and launched herself into the flow.

It was while she was passing the small post office in Church Street that a thought came to her, and she dragged her brother inside. It was jam-packed with people but if she didn’t do this now she would probably forget.

‘What are we doing here?’ Ben demanded. ‘I want my dinner.’

‘I’m going to send Aunt Connie a postcard,’ Jennet replied, gently pushing through the bodies till she came to the rack.

‘Can’t I go home now? I’m starved.’

Jennet ignored him and studied the collection of cards. It was a picture of the abbey that she eventually chose and she squirmed with it through to the counter. Strangely enough, nobody else seemed to be buying anything. Jennet put her postcard down and looked through the glass at the postmistress.

‘Can I have this and a first class stamp, please?’ she asked.

The woman was about fifty. Her greying hair resembled a dilapidated haystack and the sides of her mouth twitched nervously. Jennet eyed her neat, beige cardigan. There was a crumpled tissue poking out from one sleeve, in case of emergencies. There was no wedding ring on the woman’s finger and Jennet guessed that here was one of the town’s spinsters, and smiled unconsciously.

The postmistress blinked in confusion, not sure why the girl had smiled at her. Up went her ringless hands, fluttering before her like frightened birds.

‘A stamp,’ the woman repeated in a flustered voice as she searched under the counter. ‘Dear me, no – television licence stamps.’ She twiddled with the chain around her neck, attached to which were her glasses. ‘Oh fly!’ she muttered. ‘I had them a minute ago.’

Jennet smiled again. The woman was a terrible ditherer; how had she ever got the job?

‘Ah,’ came a grateful sigh, ‘there you are, you terrible thing.’ She pulled a large book of stamps towards her and put on her glasses before wading through it.

‘There you are, dear,’ the woman breathed wearily. ‘That’s forty-five pence, please.’

Jennet counted out her change and while the woman waited, the tissue flashed out and dabbed at her nose, then was just as speedily consigned to the sleeve once more.

Jennet took her stamp and postcard, thanked her and looked round for Ben. He was not there. Then from the street came a terrible commotion; a car horn was blowing harshly and voices were raised in anger. Jennet put her hand to her mouth and ran outside, thinking the worst.

A large old Bentley was attempting to plough down Church Street and the driver was being none too gentle. Jennet found Ben on the pavement, laughing at the surprised and angry looks of the people who were thrust aside. A girl in a bright orange and purple dress that had little mirrors sewn around the hem shouted equally colourful abuse at the occupants of the car and shook her tambourine at them furiously.

Once Jennet had got over the relief of finding her brother in one piece she shook him roughly and angrily told him, ‘Don’t you ever, ever do that again! Do you understand?’

But Ben was not really listening. He was still staring at the car, which had pulled up outside the post office. The driver was a bluff Yorkshire man in grubby gardening clothes, but on his head he wore a chauffeur’s cap. He got out and walked to one of the rear doors.

‘’Ere we are, madam,’ he said gruffly as he opened it. Both Ben and Jennet peered inside to see who his passenger might be.

A large, flabby lady in a silk print dress and a fur stole stepped heavily on to the pavement. Her hair was a pale peach colour and there seemed to be an inch-thick layer of make-up covering her face. Her lips were smeared a sickly orange to match her rinse, but it just made her look ill. She wore a necklace of pearls and her podgy hands were bejewelled with rings.

Jennet thought she looked like a fat pantomime fairy. Ben began to giggle as the apparition waddled gracelessly towards the post office and brushed past them. Her perfume was incredibly pungent – he could almost taste it.

The woman peered down her nose at the children and gave a peculiar excuse for a smile. Ben scowled. This was one of those phoney acknowledgements, the sort the Rodice used to dole out. Jennet nodded at her and shuddered as she wobbled into the post office; there had been lipstick all over her teeth.

‘Come on,’ she said to her brother, ‘let’s go and have lunch.’

They found Miss Boston already in the kitchen making ham sandwiches for them and, as they sat down to eat, they told her what they had done that morning. The old lady listened attentively, clucking now and then in wonder or approval. She laughed as they described the morris dancers and sucked in her cheeks at the disgraceful behaviour of the Bentley.

‘That Banbury-Scott woman really is too much!’ she snorted. ‘Thinks she owns the town, she does.’

‘You know that fat lady with all the kak on her face, then?’ asked Ben, forgetting his manners.

Aunt Alice spluttered at this description, pursing her lips and raising her eyebrows to disassociate herself from it. ‘Yes, I know her,’ she said. ‘She just happens to be one of the wealthiest women in the town. Married well, you see – married twice, actually, but both her husbands are dead now. Mrs Banbury-Scott is a very important person; her home is one of the largest and probably the oldest around here.’ Miss Boston sighed wistfully and took another bite of her sandwich.

‘She’s very fat,’ Ben said again.

Jennet kicked him under the table but Aunt Alice nodded in agreement. ‘Yes, she is a bit of a pig,’ she admitted. ‘Far too greedy, I’m afraid.’

Ben chuckled with surprise and appreciation – he had not expected her to agree with him.

‘I didn’t like her,’ said Jennet flatly.

‘Not many do,’ confided Aunt Alice, ‘but because she’s rich they put up with her. Very useful to have her on the board of this and that if she makes a contribution to the funds now and again. Of course she’s got terribly above herself – putting on airs and graces. She might be able to fool some of them round here with her fancy ways but I remember what she was like before she got married. Plain Dora Blatchet she was then, father lived in the yard opposite – simple fisherman.’ She leaned back and stared into space for a moment. ‘Oh, but she was a lovely creature then – prettiest little thing in Whitby. Another cruel trick of age.’

Ben licked the crumbs off the plate and looked round for something else. Miss Boston gave him an apple but he looked at it woefully; he had been hoping for some chocolate biscuits.

‘She can’t have any real friends, then,’ said Jennet thoughtfully. ‘How awful to be liked just because you have money.’

‘Oh, but she does have friends, dear,’ Aunt Alice quickly put in. ‘There’s Edith Wethers, the postmistress, Mrs Joyster, Tilly Droon and . . .’ here she paused, then added guiltily, ‘. . . and there’s me. In fact Mrs Banbury-Scott will be coming here tomorrow evening. Our ladies’ circle meets once a month.’

She cleared the plates away while Jennet puzzled over her words. The way Aunt Alice had mentioned the ladies’ circle was strange, as if she was embarrassed and did not want to talk about it.

‘Is it a party?’ Ben asked with interest.

Miss Boston gave a nervous laugh and shook her head quickly. ‘Oh no, Benjamin,’ she said. ‘Just a collection of dreary old women like me – extremely dull, I’m afraid.’

Jennet looked across at her brother. It was obvious they were not wanted at this meeting and she wondered what they were supposed to do during it.

By a strange coincidence, Aunt Alice was thinking exactly the same thing. The old lady stuck out her chins and chewed the problem over in her mind. It would never do for the children to find out what happened at these meetings and discover her little secret, she told herself. Jennet watched her and suspicion began to form in the back of her mind, but for the moment she said nothing.

The rest of the afternoon was spent listening to the various little pockets of folk music that sprang up wherever a clear space could be found. Ben enjoyed this immensely and joined in the clapping and cheering. There was so much to see that the time passed very quickly and the children were exhausted by the time they eventually clambered into their beds.

Another loud chorus of screeching gulls startled Jennet out of her sleep the next morning. She glanced at her watch: it was half past six. With an exasperated groan she turned on her side and lifted the edge of her bedroom curtain.

The day was wet and windy, with gulls riding the gusts and circling overhead. Jennet’s room looked out on to the yard but nothing stirred there. She fumbled with the catch and opened the window.

At once the drizzly Sunday morning crowded into her bedroom. The clamour of the sea birds rang in her ears and the warm wind blew salt and rain into her face. From somewhere, the delicious and enviable smell of frying bacon tantalised her senses. Quickly pulling her clothes on, Jennet stumbled downstairs to make her breakfast.

In the kitchen she found that Miss Boston was already up and about. She had evidently just returned from her morning walk, as her white hair resembled the collection of sheep’s wool and twigs on the hall table.

‘Hello, dear,’ she said, looking up from the kipper on the plate before her. ‘Sleep well?’

Jennet nodded. ‘Yes, thank you.’ She slotted a piece of bread into the toaster and decided it was time to ask what had been preying on her mind. ‘Aunt Alice,’ she began casually.

The old lady pulled a fishbone from her lips and glanced up. ‘Hmmm?’

‘When will your friends be coming today?’

Aunt Alice coughed and hastily covered her mouth. ‘Gracious!’ she exclaimed in a fluster. ‘I must have swallowed a bone by mistake – tiresome thing!’ She took a drink of coffee, wondering all the while what the girl would ask next. ‘They usually arrive after tea, Jennet dear,’ she answered eventually. ‘Why?’

‘I just wanted to know if you wanted Ben and me around,’ Jennet replied as the toast popped up. ‘We could stay upstairs, if you like.’

Miss Boston took hold of Jennet’s hands, which by this time were holding the butter knife and the toast. ‘Oh, do you think you could, dear?’ she said gleefully puckering up her wrinkled face. ‘That really would be such a help. Some of the circle are not very fond of children and we do need to concentrate, you see.’

‘Don’t worry,’ Jennet said. ‘I’ll take Ben on a long walk this afternoon to tire him out. You won’t hear a peep from him all night.’

‘Oh, you are considerate, thank you again.’ But Miss Boston’s face as she bent her head over her plate once more seemed far from happy.

The girl turned back to the toast and grinned. She had guessed correctly: the ladies in the circle were secret gamblers.

Nothing titillates old ladies more than gambling for money, be it Bingo or Bridge. Jennet decided that Aunt Alice was being so furtive because she was too embarrassed to admit it. She crunched through her breakfast and stared out of the window. I wonder what they play? she thought to herself. It must be cards, she decided. Gin Rummy or Whist, perhaps, or maybe even Poker. The thought of all those old women sat around a table playing Poker like cowboys in a wild west saloon greatly amused her. She imagined Mrs Banbury-Scott in a ten gallon hat and nearly spat out the toast with her laughter.

Aunt Alice frowned to herself. Could Jennet have found out somehow? Perhaps it was not too late to cancel tonight’s meeting. She took another gulp of coffee and fixed her eyes on the remains of the kipper as though it were to blame in some way. I must make this the very last meeting of the circle, she insisted to herself. It will get too dangerous if the children become involved – especially for Benjamin.

Ben was sleeping soundly with his ammonite clasped firmly in his hand. He had been dreaming of snakes and dragons all night – he was the valiant hero who slew them. The dream was just coming to a ridiculous conclusion, as his usually did, with a grand parade of headless serpents wriggling behind him on brightly coloured leads whilst he fed cat munchies to the heads bouncing round his ankles.

‘Ben, Ben,’ shouted one of the heads, ‘wake up, you lazy lump!’

He rolled over and pulled his bedclothes higher.

Jennet was in no mood for this today. ‘Wake up, thickhead!’ She dragged the blankets off him and he flapped about like a headless serpent himself. Then he glared at his sister and brought his bottom teeth over his lip to show annoyance.

‘You and me are going for a long walk today,’ she told him sharply. ‘So come downstairs and help me make a packed lunch.’

‘Where we going?’ he asked, wishing he could stay in bed all day. But she had already left the room.

The drizzling weather was soon blown inland and by midmorning the sky was blue. Aunt Alice waved the children off, but her heart was troubled and she watched them leave with a guilty look on her face.

It was late when they returned, making their way through the town. The children crossed the bridge to the East Cliff and wearily tramped up Church Street.

‘My dears!’Aunt Alice sighed with relief as they opened the front door. ‘You’ve been gone an age, I was beginning to worry.’ The old lady stared at their tired faces and tutted. ‘My goodness, you are a dozy pair, and look at the state of you both. I’ll turn the immersion on so there’ll be plenty of hot water.’

Some time later Ben lounged in his bed. He had been fed, had bathed himself and was now reading a brand-new comic which Miss Boston had bought for him. It was a warm night so he had only put on his pyjama bottoms. The sheets were crisp and clean, smelling of the linen cupboard, and he felt new all over as he wormed into them, tired and contented. From the bathroom he could hear Jennet stepping out of the bath and downstairs Aunt Alice was setting out her best china cups on a tray. She was humming to herself and the sound drifted up to his room.

Ben’s window did not overlook the yard so he missed the arrival of the old lady’s guests. A sharp knock on the front door vibrated through the cottage and startled him. He sat up and listened to see if he could hear who it was as Miss Boston let the newcomer in. A brisk, abrupt voice dragooned up the stairs – that must be Mrs Joyster, he thought to himself. Just then his own door opened and Jennet, wrapped in a towel with another turbaned around her wet hair, looked in.

‘Was that the army woman?’ he asked her.

Jennet glanced behind her and shrugged. ‘I think so,’ she said. ‘Now, have you got everything you want? You’re not to go downstairs tonight, do you understand?’

Ben nodded but Jennet recognised the look in his eyes and waved a warning finger towards him. ‘If you so much as sit on the top step there’ll be trouble, OK?’

Ben threw himself on his back and raised the comic over his head sulkily. Jennet closed the door and went to her own room. She heard some more guests arrive, and recognised Miss Wether’s voice and that of Miss Droon.

The postmistress was sneezing and asked for a glass of water. ‘I just can’t sit next to Tilly tonight,’ came the muffled twitterings. ‘All that cat fur brings on my – achoo!’

Jennet smiled to herself; the tissue would have its work cut out tonight. She dried her hair and began thinking about the card sharps downstairs. This time she wondered what the stakes were – just how much did the old dears play for? Perhaps it was only ten or twenty pence. What if it was more than that – a pound or two? Maybe the gambling fever was so strong that a whole week’s pension was frittered away in one night. A new idea came to her as she tugged at a tangled clump of hair with her brush. What if Aunt Alice was in league with the others to swindle Mrs Banbury-Scott out of all her money? Jennet smiled at her own fanciful imaginings and just hoped the cards would favour Aunt Alice tonight. It was probably nothing worse than a game of Happy Families, she concluded, putting the hair-brush down.

The light faded outside Ben’s window and the shadows deepened in his room. The boy fell into a light, uneasy sleep which was invaded by unpleasant dreams. In them he was walking down a long, narrow corridor which seemed familiar, but he couldn’t think where he had seen it before. His feet were heavy in the dream and though his legs were moving he never got anywhere. Beads of sweat pricked Ben’s forehead as he turned over and his breaths came in short gasps.

He knew there was something behind him but he could not turn his head round to look. He could feel its presence dogging his every footstep, its eyes burning into his back; he sensed the tension in the air as it prepared to spring. A howl boomed inside his head, a weird, unearthly sound that slashed the watchful night. With a hideous growl, the unseen beast bore down on him.

The boy whimpered in his sleep, trapped in a nightmare which was rapidly approaching its gruesome end. His face was screwed up in fear. ‘Go away,’ he mumbled tearfully, ‘make it go away!’

But the horror continued. The creature was snapping at his heels and with a shriek he called out, ‘Mum! Mum!’

Ben found himself sitting up in bed, drenched with sweat. The room was dark, yet he could make out the figure sitting beside him quite clearly.

‘Mum,’ he whispered.

The figure smiled at him, as any mother might do to comfort her child in the night. Ben put his arms out to embrace her but she rose and backed away. It was then that he remembered she was dead.

He rubbed the sleep from his eyes and wondered how he could have mistaken this vision for something real. A thread of silver light ran around her outline, flickering like sunlight over water. His mother opened her mouth, but Ben could not hear the words she was speaking. He averted his eyes quickly when he saw the pattern on the wallpaper through the darkness where the roof of her mouth should have been. He knew there was nothing to fear but it unnerved him and he found himself wishing she would leave. Watching his own mother mouthing dumbly like an actress in some crackly silent film was horrible.

The boy hid his eyes and waited for her to disappear – his visitors usually left if he ignored them. But when he looked up she was still there. She had moved to the end of the bed and was kneeling down with her face turned sadly towards him. She had stopped trying to talk, as if she realised that it was upsetting him. Instead, she shook her head at her son with that gentle smile on her lips which he remembered so well. That was better; Ben smiled back at her. She then inclined her head towards the door, beckoning Ben with her hands.

Puzzled, the boy clambered out of bed and shivered; his sweat had become cold and he was chilled. Stepping up to the door, he looked up at the shade of his mother and asked her with the expression in his eyes what she wanted.

The figure pointed at the door knob. Trembling, Ben reached out a hand, slowly opened the door and peered out.

He was totally unprepared for what was on the other side and gasped in disbelief.

There, crammed on the small landing, was a multitude of ‘visitors’. They were sitting on the banisters and crowded down the stairs. Ben could only shake his head and stare; he had never seen this many together before. The ghosts of over a hundred people were there. There were young faces and old, some wearing old-fashioned costumes and others dressed in clothes more familiar to him. But they all seemed to be waiting for something. A long line of them trailed down into the hall and gathered outside the closed parlour door.

Although Ben did not understand why he saw his ‘visitors’, they sometimes seemed as real and ordinary as the rest of the world – the Rodice’s husband had been one of these. But he could tell these forms were phantoms. Some of them were transparent as glass, whilst others were just indistinct shapes made of grey mist.

As he opened the bedroom door a little wider to get a clearer view, they suddenly became aware of him and all their faces turned in his direction. For a moment Ben felt afraid and he pulled himself back into the bedroom. But his qualms disappeared as the light which flickered around the apparitions welled up and illuminated the stairwell from top to bottom with a beautiful radiance.

The blaze lit his face and he glanced up to find his mother. She was no longer at his side and it was some moments before he caught sight of her again in the hall below, motioning for him to follow.

Ben stepped on to the landing and instantly regretted it. Every soul rushed towards him. They gathered thickly round, pressing in on all sides, their eyes imploring him to help them. They wrung their hands piteously before his face, their expressions desperate with the need to communicate with the living. He never actually felt them touch him, but it was suffocating all the same and he hated it. It was like being surrounded by beggars and knowing you had nothing to give them. The pleading faces were images of sorrow and regret that burnt into him, and a claustrophobic panic began to bubble up inside. He had never experienced anything like this and it frightened him; what were these spirits doing here and what did they want? It was as if they had been dragged here against their will and were beseeching him to release them.

‘I can’t hear you,’ he wailed helplessly. ‘Stop it, stop it!’ The boy closed his eyes tight shut and struggled along the landing. He had to escape from this clamouring madness and he groped for the door to Jennet’s room. The throng of spirits parted before him like scythed corn.

There it was, the doorknob. He fumbled for a moment, opened his eyes and flung himself inside.

‘What’s up?’ asked his sister in mild surprise. She was reading one of Aunt Alice’s books in bed and had obviously not heard a thing. But once she saw how pale and frightened her brother was, she hastily put the book down and held out her arms to him.

‘Oh, Jen!’ he howled, throwing himself at her. ‘They won’t leave me alone, Jen, I can’t hear what they’re trying to say. Tell them to go away, will you? I’ve never seen so many of them before.’ He sobbed into the large T-shirt she used as a nightie and the rest of what he said was unintelligible.

Jennet stroked his hair and tried to soothe him. It was a long time since Ben had had one of his turns and she wondered that he should have one now – he seemed to be so happy here.

‘Are you . . . are you seeing things again, Ben?’ she ventured.

He nodded into her shoulder. ‘Mum’s here, too,’ he cried. ‘There’s so many, Jen.’

Jennet pushed him away from her and looked steadily into his eyes. For a moment all her old suspicions about his visions had flooded back, but no, he was really scared. ‘Don’t worry,’ she told him calmly, ‘I’ll take a look outside and make sure there’s no one there.’

She got up and crossed to the door but Ben sprang past her and slammed himself against it violently. ‘Don’t go out!’ he begged. ‘You’ll let them in!’

Jennet was beginning to get worried; he had never been this terrified before. She wondered if she ought to go and ask Aunt Alice’s advice. Would she mind the interruption? This certainly seemed urgent enough.

‘Don’t worry, Ben,’ she said, pulling him from the door. ‘I won’t let anyone in, I promise.’

The boy backed towards the bed as she turned the knob and opened the door. She could see nothing out there – but he could. On the landing the crowd of souls raised their arms and surged forward. Ben screamed and collapsed on the bed.

Jennet was horrified. She raced down the stairs, calling for Aunt Alice at the top of her voice. Up to the parlour door she ran and, without knocking, thrust it open and charged inside.

A red light fell on her. For a moment the girl was confused by it, but as she looked around to find its infernal source, the truth of the situation she had stumbled into was revealed.

Seated at the round parlour table was the ladies’ circle: Miss Wethers, Mrs Joyster, Miss Droon, Mrs Banbury-Scott and Aunt Alice. They were all holding hands and looked extremely startled by Jennet’s entrance. She had interrupted a seance.

For a second Jennet could only stare back at them. Miss Wethers made an uncomfortable squeaking noise and pulled her hands away from the table to reach for a tissue.

Aunt Alice sucked her cheeks in guiltily. ‘Oh dear,’ she began, but did not know what else to say.

Jennet was speechless. She watched as Mrs Joyster tutted at her inconvenient arrival and left the table to switch on the main light. Then she leaned over the small lamp which had been fitted with a red bulb and clicked it off. ‘We’ll get no more tonight,’ she huffed disagreeably, and fixed the girl with a withering glare.

Anger quickly replaced the surprise which Jennet had at first felt. All this time Aunt Alice had deceived her! She felt cheated and used – the old woman wasn’t interested in her at all, she just wanted Ben because of his gift. Her resentment welled up until she could contain it no longer.

‘I hate you!’ she stormed. ‘You’re nothing but a load of old witches!’

She slammed the door shut and stomped upstairs to pack her things and Ben’s. They weren’t going to stay in this house any longer; she didn’t care where they went just so long as they got away.

‘Who was that?’ asked the fat Mrs Banbury-Scott, as she reached over to a plate of scones and crammed one into her gaping mouth,

‘That young lady has completely ruined the sitting,’ repeated Mrs Joyster, snorting in disgust.

Another scone disappeared into the Banbury-Scott cavern. ‘Most disagreeable child. Mmmmm . . . didn’t I see her outside the post office yesterday?’ She paused to give her tongue an airing as it came across a most peculiar taste. ‘What did you put in your jam, Tilly darling – catnip?’

Miss Wethers stared at the closed door unhappily. ‘Oh my,’ the mouse whined. ‘She didn’t seem very happy.’

Aunt Alice wiped her moist eyes. ‘No, she didn’t, did she?’ And the old lady covered her face in shame.