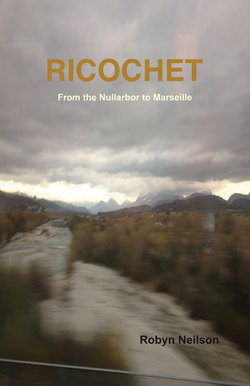

Читать книгу Ricochet - Robyn Neilson - Страница 2

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Prologue

ОглавлениеA lone woman sits at a scratched table in a bleak hut. Alone, but in rapture with all that is good and bad about love and solitude. She has attended to all the morning's chores, listened to La Bande Originale, and now is silent and uncertain of what to do next. The shutters are closed against the assault of the mistral. Being inside and still leads her to a kind of contemplation, an interrogation of loss: a haunting of her new husband and his family. Wondering dogs her. Not that at times she does not despise this her only friend, but she learns to be led.

Thus her memory meanders, like her wayward sewing threads: the weft of time weaving it into line, not as chronological time, but as sensory time. She imagines the donkey trails of old France, their meaning revived and rewritten each time she attempts that same route from one place to another. The woman wants to keep a record because she has little else to do. She imagines the writing will bring to her daily life a purpose; a semicolon against the unravelling. Nothing grand will be achieved, rather a steering away from the spectre of loneliness, the shadow of a spell, causing her to pause and draw deep breath in the place in which she stood.

That place is France; and three distinct places within, which she summons as if they are something she has swallowed. Where she begins the remembering is a derelict mobile home rented from gypsies. A hut with three views: the first being the outdoor latrine which she and her husband dug in turns, grimacing at the limestone, and over which she cobbled together a shelter; their second view being the cyclone fence of a rifle range which could not conceal the beauty of trees beyond it; and their third view, which she ingested without being close enough to savour or inhale, being the distant hills of Les Alpilles in their soft violet blue rise and fall, reminding her of home in Australia.

But Freya had had two previous homes in France. The first was Auriol, the second La Ciotat. She writes out of necessity: to explain to herself her alteration. To tell of how each place grew into her, grafting her. Finally she realizes that being untethered from home puts her on the path between all of her homes. It is along that path where Loup and she found each other, deserted each other, and where she later returned, believing that she might retrieve what they had lost. The woman alone. Her ego resisting the idea that she is no longer young, clings to the idea that memory is the salve to prepare her for what is to come.

Freya suddenly finds her beginning. She shoves her chair back on the faux-timber plastic floor, pleased with the result of her morning’s sweep and scrub, and strides a couple of metres to their bed, squeezing sideways between the bowing wall and her side of the bed to retrieve her secreted ‘emergency’ two litre bottle of water, and her laptop which she hides under the mattress. She boils water on the camping stove, inhales deeply the aroma of her Orange Pekoe Broken Tea Leaves, (the intriguing and exact title of the leaf tea she has triumphantly found in the distant Carrefour supermarché), and arranges her laptop on a pile of books on top of her bike box.

Freya decides she will write whilst standing.