Читать книгу Ricochet - Robyn Neilson - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

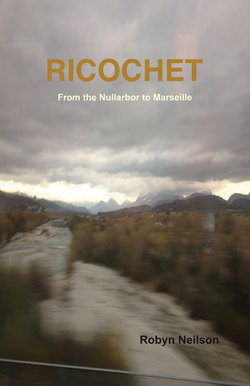

Our Wedding, December 2008, Descartes Bay.

Оглавление“A fantastic figure he always was, half of fun and half of diabolism; with a very slight alteration, he might have sat and stared down, on the top of the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris.” Karen Blixen, ‘Out of Africa’

Our Wedding is the third thing, which happened a decade later, in a remote Lighthouse in far southwest Victoria. Every minute of those years of separation, I never doubted that Loup was the man. His conviction turned out to be equally tenacious. But it was not until the morning of my 51st Birthday, nine years since we last saw each other, as we awoke in our tent on the side of a French mountain, that Loup finally proposed. Five months later, we had appeased the quaint French legalities; ‘publishing the bans’ of our intended marriage in the local town hall where Loup resided. It was my job to organize the rest, as Loup was tied up with work in France. The week before the big day, I picked Loup and his older brother Pascal up from Melbourne Airport at 2.30am. It was Christmas Eve.

We drove in the dark up the hills of the Dandenong Ranges, where we would rest for two days. And that is where I first got to know my brother-in-law. Along with Maya, my husky who formed a quick attachment to Pascal, we stayed up talking until 4.30 a.m. When Loup and I awoke late, Pascal was sitting out in the sun, shirt off to feel the full impact of the Australian summer, Maya curved into his side. Pascal appeared modest in character, but not in body. His body was his temple, his vanity, which he worked into a sculpted muscle machine. Unlike his little brother, who took for granted his slender boyish bones and their inherent athleticism.

We took two days to reach my cottage by the sea. Two days and nights of consolidating a friendship. I did not realize then, just how little time Loup and Pascal had spent together in their homeland as young men or adults. This was a rare time of reconnection for the brothers. However things turned sour when we reached my house. Whilst I had been absent, the rampant garden had pleased itself, and then fallen prey to a windstorm. As had the flies and ants and spiders, sprawled on every surface of the house. I swept and chided. Then got the mower out. Of his own accord, Pascal strode into the shed, found saws and rakes and started attacking the wayward shrubs and fallen branches. Working flat out to get everything in order before my family descended for their one and only visit, I mowed and raked, pruned and raked. Pascal sawed and chopped, hauled and piled. Loup on the other hand sat inside. Dusting off and cleaning all my photos with slow precision. But I could not understand his timing. Went wild with frustration. Not knowing yet how much Loup detested gardening.

‘Please honey, can’t you see the mess out here? Dad will be horrified; can’t you come out and help us? Leave the photos, we can all do that tonight when it’s dark!’

Loup quietly got up, put the photos back on the bookshelf, looked at me with disgust, and if I’d looked more closely, hurt, and left.

He did not return for hours. A promising prelude to our marriage in two days.

Managing the next day to somehow put that behind us, we went to see our minister, a childhood friend happy to offer us a ceremony unfettered by my childhood zeal. She was curious to know if we had discussed or written our vows.

‘What are they?’ asked Loup, ‘Oh, you mean where the woman has to obey the husband and stay, for better or for worse?’

We were not sure whether to laugh at the anachronism, or the fact that Loup was serious. Seven years later, one of his standard lines is ‘for what did I marry you, if not to fetch my glass and serve me?’ The French in him plays with the assumption; the cynic in him applauds the joke. And the angelic part off him inspires the will in me to do it. I look back and the laugh is on me; that day before our marriage, because I do serve and sweep and wash for Loup, for better or for worse. And therein lies the rub chaffing away the gift of my emancipation. Unless of course there is the invitation to do a deal: ‘une bonne pipe’ in exchange for a job done.

Participating in a social event is not Loup’s forté, let alone his own wedding. Although he had been spared many of the arrangements; even choosing our rings together. Over the phone between France and Australia, we had both agreed on simple and inexpensive. So Loup suggested plumbers O-rings would be perfect. He was not joking. When I found myself in front of a Melbourne jeweller who was talking French on the phone to his cousin in Strasbourg, Loup’s hometown, I thought this must be a sign. I put on hold a matching pair of bands. However, they did not appeal to Loup. Now with only twenty-four hours to go, we raced off to a local jeweller, so that I could avoid an O-ring, and help purchase something more meaningful. Or at least more beautiful. We found an antique style ring, and for Loup, his simple band.

Loup had volunteered for one task; to design and print our invitations. One of his ideas proved offensive to my Australian friends… the facetiousness of his French humour, too much. A favourite game of mine is ‘Hang the Butcher’. I badger Loup to play it in his language, as a way of improving my vocabulary. He does not enjoy it as much as I. Hence, Loup used the stick figure image of himself hanging in a noose, and me looking on with a smug smile, as our wedding invite. Even friends whom I thought had a caustic wit didn’t laugh.

One might conclude, along with Zena and my mother when they suggested that ‘perhaps I had persuaded Loup into marriage’, that in fact they and the sceptics were right. My own insecurities needed no further encouragement, so when I put this to Loup, he sighs, bored by the doubting,

‘Freya, have you ever known me to do something I haven’t wanted to do? I have thought about this for a very long time…je suis sûr et certain. Je crois dur comme fer. Firm as iron. By the way, chérie…?’

This is true, that Loup is immovable; truer than any other discovery I have since made about him. Once, out of the blue years later, when I was chopping up timber palettes to feed our pot belly in the hut, Loup looked up from his calculator and said,

‘I have only one regret Freya, that I didn’t marry you sooner.’

Despite all of these seeming contradictions, our day dawned: a brush of bold blue after a week of grey. A brisk south-easterly ruffled the white caps way out to the horizon. Friends and family worked together to create a feast at the foot of the Lighthouse…. fabulous in every way. We had a guide who might have swaggered off a galleon centuries ago, to take us all up to the big light. Thirty of us in heels, bow ties and hats, champagne flutes teetering, silken scarves, and me dressed up in my grandmother’s cotton lace petticoat. Our excitement floated, our best fabrics furling up the steep spiral stairs. We burst out as if from a chimney, the daylight on top blinding. Clutching the iron railing outside as the wind blew each hair-do asunder, we huddled against the curve of the white stone, small children clinging to the legs of our fathers, our gaze steeled by the sea pounding below. We put our fingers to our faces, wiping away the wet spume as it buffeted high in white puffs. In unison, we gasp as someone yells,

‘Look there, Blue Whales!’

Mesmerised by their plumes of spray… by the magnitude beneath that we figured to be a mother and two calves, surprisingly close in.

‘That is a real sign, the best wedding gift’, says our whale biologist friend. ‘Our team has been searching for a month; we knew they’d arrived from Antarctica, but we couldn’t sight any! And here they are… for you.’

Little did I know, that around the other side of the narrow balustrade, another gasp ensued. Our guests watched in disbelief as Pascal leapt, agile as a monkey, up onto the railing, camera in hand. He was not holding on to any support. Nothing. Nothing at all to prevent him from plummeting the sixty feet below onto the rocks, down through those flimsy white puffs of spray, his corporeal temple to be dragged away in shards by the unknowing waves. Preserved in an Antarctic iceberg. Or carried under a container ship that Loup and I have since watched leaving our sister cities, Melbourne and Marseille. To end as un grain de sable in a La Ciotat sandcastle.

Loup and I learn of Pascal’s tightrope act later.

‘Pascal has always shown off like that….’ says Loup, matter-of-fact. ‘He’s always taken risks, walked out beyond where there was no scaffolding…. Tempting fate.’

But those who saw Pascal balance on that Lighthouse railing on the day of his little brother’s wedding, did not see this as an act of bravado. They saw it as an act of a man for whom the idea of death was ho-hum. We did not know then how intimate death and Pascal had become.