Читать книгу Always Eat Left Handed - Рохит Бхаргава - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеchapter 1

The Pomegranate Principle

“Whatever happens, I can’t let them

see the inside of my book.”

This wasn’t what I expected to be thinking as I was getting ready for my first interview to launch my new book.

It was just weeks before Personality Not Included would go on bookstore shelves and already my months of planning were being pushed off track.

The day before, my publisher McGraw-Hill had sent me a sample of the dust jacket in advance of my planned book tour with a short apology that the actual book wasn’t quite ready yet. I had a cover, no book, and my first big interview was in less than twelve hours.

I was starting to panic. Should I cancel? Try to reschedule? Do the interview without the book?

Finally, I had an idea. I started combing through my bookshelf to see if I had another book that was about the same thickness and dimensions as my soon-to-be-completed book. I found one and wrapped the jacket over top to see how it would look.

It was a perfect fit.

Almost immediately, my mind filled with all the worst-case scenarios. What if I had to open the book during the interview? What if I had to read something from it? I was already imagining a moment when my entire charade would be embarrassingly exposed for the online world to see.

Still, I decided to do the interview anyway.

The next day I showed up to the interview and proudly held up my book cover, fitted carefully on top of a worn copy of Made to Stick. I made it through the interview without my secret being exposed.

Many years (and interviews) later, I realized just how silly my concern had been. No one ever asks you to read from a business book during an interview. And no one, from a brief look, can tell that the interior of a book doesn’t match the dust jacket anyway.

Of course, at the time I didn’t know any of that and my problem felt monumental. Looking back, the “secret” to surviving that situation was self-confidence. The kind of self-confidence I had been sorely lacking nearly a decade earlier when I had what I not-so-fondly remember as the worst meeting of my life.

how to fail miserably at selling your idea

The year was 1998 and I had an idea that I thought was going to change the fine dining industry. At the time, very few restaurants had a website and so I had come up with an idea to use the Internet to bring these restaurants into the 21st century (literally, since it was still two years until the year 2000!).1

My business model consisted of services (getting restaurants to pay me to build their websites) and media (creating an online directory of websites that would become the place for anyone to find a restaurant).

To start, I registered the domain name www.dc-restaurants.com for my directory and then started my efforts by going door to door in a part of Washington, D.C. called Georgetown to try and convince restaurant owners to pay me $200 to build their website. Everyone asked me the same question: “Why would any restaurant need a website?” It was, after all, still 1998.

After more than a dozen rejections, I decided to go to one restaurant and offer to build their website for free just so I could pretend I had a paying client and entice other restaurant owners to give me a chance. After I built that site, I listed it on my directory along with the handful of DC area restaurants who already had websites that I had found online. Then I visited a few more restaurants. Even that didn’t work.

As a last-ditch effort before giving up, I had an idea. What if I could convince the dominant Internet provider at the time to list my directory and drive traffic to it? Then I could show the restaurant owners how many people were visiting my site and all the potential customers they were missing. It seemed like the perfect plan to convert those skeptical restauranteurs.

Part of what inspired that plan was the convenient fact that the headquarters of America’s biggest Internet provider at the time happened to be right down the road from where I lived. After several calls, I managed to get a meeting with one of their regional directors.

A few weeks later, I walked into the lobby of the provider, which was already better known by its acronym: AOL. My big meeting started with some quick small talk, after which the director listened to my description of www.dc-restaurants.com patiently. I talked about the vision for the site. I talked about what I wanted to do for restaurant owners. I talked about how sure I was that AOL users would be very interested in finding restaurants online.

After quietly listening to me ramble on for about ten minutes, he said politely, “I understand what we can do for you. What can you do for us?”

Silence.

I didn’t say anything. I didn’t invent anything. I didn’t even move. I just sat there. I didn’t have an answer because I didn’t have enough confidence to recall all the work I had done before.

Looking back, I realize there were plenty of things I could have said.

I could have mentioned the research I had seen about how more and more consumers were looking online for restaurants but that there was no directory of restaurants in our area yet. I could have told him about the few successful directories like mine that I had found in other cities which seemed to be thriving. I could have even told him about how I had researched AOL and knew they didn’t have a directory like this one already.

Unfortunately, none of those facts came to mind, because I was too nervous. I failed because I didn’t have the confidence or knowledge to be able to come up with a good answer to his reasonable question in the moment when I needed it.

After what seemed like an eternity, I finally said I would think about it and get back to him. I quietly thanked him for his time and escaped the room as quickly as I could. That was officially the worst business meeting of my life.

It would be easy for me to excuse my lack of confidence as a natural result of my age and inexperience. I used to think that if I had just been older and more experienced, perhaps I could have succeeded in that meeting.

Yet it seems like everywhere we look today, there are entrepreneurs who start billion-dollar overvalued “unicorn” companies and make the rest of us feel like underachievers, no matter how old we are.

Is it possible that some people just seem to earn their self-confidence faster than others? And if so, what do they know that everyone else doesn’t?

the pomegranate principle

The answer comes from a fact you will quickly discover if you ever happen to search the Internet for advice on how to deseed a pomegranate. On the Internet, everyone seems to have a theory for the correct way to do this frustrating task.

The only thing all these self-declared experts agree on is the wrong way: slicing it in half and picking out the seeds individually. Instead, one popular video suggests cutting it in half and whacking the back of each half with a wooden spoon (highly entertaining but messy). Another illustrates how you could cut it into sixths and slowly peel it apart (precise but hard to do exactly right).

Finding divergent advice like this online is something we encounter often. The challenge is knowing which advice to follow.

The Pomegranate Principle: In a world filled with conflicting advice, the ultimate skill is building and learning to trust your own intuition.

Intuition can seem like an example of a big complex thing that is hard to intentionally improve. It isn’t.

The truth is, intuition is built from the tiny observations that we all make every day. When you get a “gut feeling,” it is an example of your brain using a memory from your past to help explain the present. Scientists call this pattern matching and human brains are great at it.

That’s why it pays to focus on the details—no matter how small or insignificant. What if tiny little “life hacks,” like learning how to deseed a pomegranate, were the real secret to improving your intuition?

Life hacks like using club soda to soak up a red wine stain. Or turning on a seat heater to keep takeout food warm in your car. Or rubbing a walnut on damaged wood furniture.

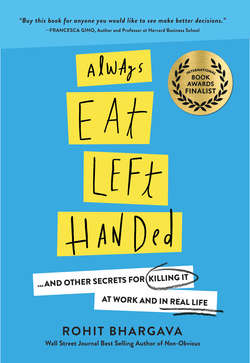

In Always Eat Left Handed, you will read about fifteen simple but useful ideas like these. To organize them, the book is divided into four parts.

The first part is called Think Better. It is all about encouraging you to be more observant, invest in yourself and how to be resilient after failure. The second part is Work Better and focuses on how to succeed in the professional workplace. You will learn about why it matters to have professional empathy and integrity, and why job descriptions and being on time are both overrated.

After that, the third part of the book is all about how to Communicate Better and offers a deeper look at the backstory behind my illogical disgust for cauliflower, why you should interrupt often and the power of simplifying and telling better stories. Finally, the fourth part includes ideas for how to Connect Better, including the unexpected benefits of cross-dressing and why you might want people to steal your ideas.

Each of the secrets is shared through the lens of a personal story, with minimal buzzwords and told as briefly as I could make it. For each, you will also get real actionable advice for how to put that idea to work in your personal or professional life, and why it matters.

When you are left handed, you are forced to see the world just a bit differently than other people. Regular everyday items like scissors or can openers just don’t work for you.

Being left handed means you have to get better at finding your own solutions to life’s tiny problems. That is a mentality we can all embrace, no matter which hand we happen to prefer.

So let’s get started learning how to do it.