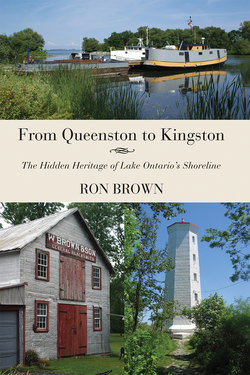

Читать книгу From Queenston to Kingston - Ron Brown - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 3Lake Ontario’s “West Coast”

Starting in the west end of Toronto, the Lake Ontario shoreline bends noticeably. From its east–west orientation east of the city, it angles markedly to the southwest, making that section of the shoreline in effect the lake’s west coast. The shore is low-lying and flat. During the last ice age, as the ice lifted from the east end of the developing water body, the bedrock there rebounded, causing the water level at the west end of the lake to rise. As it did, it began to flood the river valleys that had formed as the ice retreated. Such flooding formed several shallow lagoons at the river mouths.

These provided shelter for early vessels, and small commercial harbours developed. West of Toronto these lagoons formed at Sixteen Mile Creek, Bronte Creek, and the Credit River. While all three have their sources above the Niagara Escarpment, only the Credit attains any significant size.

According to Chapman and Putnam,1 the shoreline between Hamilton and Toronto was the result of the earlier and higher Lake Iroquois. The old lake deposited beaches of sand and gravel above the current lakeshore (later used by settlers as building materials). The soil, while light, does not enjoy as long a frost-free growing season as do the lands along the Niagara Peninsula, and therefore tender fruits could not be grown here successfully, though many did try. Apple orchards and strawberry fields, however, were very successful, but in the end could not survive another peril — urban sprawl.

Even as the ports at Dundas and Hamilton were growing and shipping out lumber and wheat, the area between York and the head of the lake remained less developed. Until 1820, the mouths of Sixteen Mile Creek and Twelve Mile Creek remained in the hands of the Mississauga. Only after the Mississauga granted them to the Crown were the vital river mouths opened for settlement.

Although a rough aboriginal trail followed the lakeshore, no route existed for stage travel until 1832, when Ontario’s lieutenant governor, Sir John Colborne, ordered the construction of a road along the shore of the lake. By 1836 the river mouths had been bridged, and stages began rolling between Dundas and York, a journey that could take up to two days.

The entire west coast of the lake is now urban; that trend is not new. In 1855, the Great Western Railway laid its tracks toward Toronto from Hamilton, giving rise to a string of stations only a short distance inland. Following the First World War, as Toronto and Hamilton grew, and traffic between them increased, a new highway opened along the shore, the Hamilton Highway. This hard-surface road spurred more development, and the little ports evolved into summer resorts and commuter towns.

The greatest stimulus to sprawl was North America’s first limited-access freeway, the Queen Elizabeth Way (QEW), which opened to traffic in 1939. Throughout the 1950s, as car ownership became universal and suburbs took over the farmland, the perils of sprawl and congestion loomed ominously in the future. Today, with no open space left along Lake Ontario’s west coast, and with the QEW almost constantly gridlocked, that future has arrived. Still, within that sprawl and traffic, heritage survives: some of it preserved and promoted; some less obvious, or simply hidden.

Wellington Square

Today it is better known as Burlington. In 1798, Mohawk Joseph Brant received a grant of over 1,400 hectares along the shore of Lake Ontario as a reward for his service to the British Army during the American Revolution. Following Brant’s death in 1807, his land was sold back to the Crown. One of the early developers of those lands was Joseph Gage, who named the site Wellington Square, after the Duke of Wellington, hero of the Battle of Waterloo (1815). As settlers began to flow into the region, Wellington Square grew from a cluster of sixteen simple homes in 1817 into a community of four hundred residents by 1845.

With few natural harbours along Lake Ontario’s west coast, the three wharves at Wellington Square were exposed to the waves, as were the individual wharves at Port Nelson to the east and that at Port Flamborough in Aldershot. William H. Smith, in 1851, noted:

Had Wellington Square possessed the advantage of a good and well sheltered harbour, it would have become a place of considerable importance, it being a convenient shipping place for a large extent of back country. As it is its progress is but slow, and property does not appear to have risen greatly in value. For a short time during each spring and fall, while Burlington Bay is locked up with ice, the steamboats run from Toronto to the Square from whence passengers and the mails are conveyed by stage to Hamilton.2

In 1855, the Great Western Railway extended its tracks from Hamilton to Toronto, locating its station several kilometres to the north of Wellington Square. In 1875 the Hamilton and Northwestern Railway laid its tracks right along the beach strip and through the centre of the town, bringing with it hoards of vacationers. Joseph Brant’s house, which was still standing at that time, became a tourist hotel known as Brant House, which offered croquet, dancing, ice cream, and twenty acres of gardens. Shortly after, the Hotel Brant opened next door and outdid the old Brant House by offering fine dining, electric lights, and elevators.

But the rail age also meant that the ships were now bypassing the west coast ports in favour of the larger facilities at Hamilton, thanks in large part to the improvements on the Burlington Canal. In 1873, when Wellington Square incorporated as a village, the name was changed to Burlington, its population having swelled to eight hundred. Among its industrial assets were grain warehouses, a carriage factory, and a wire factory.

Agriculture changed from grain-growing to the growing of apples and market garden crops, all of which could now be shipped by train, year-round, to the growing urban markets of Toronto. The Canadian Canning Company replaced the grain elevators at the foot of Brant Street. A short-lived streetcar line linked downtown Burlington with Oakville and Hamilton, but by the 1930s was gone. The opening of the QEW in 1939 and the post-war boom in suburban growth changed the face of Burlington, from that of a rural community to that of a suburb. The opening of the Ford Motor Plant in nearby Oakville led to more housing, and, in 1974, Burlington became a “city.”

Guests relax on the veranda of the popular Brant Hotel in Burlington. The hotel was one of many that lined the lake in the area of Burlington’s beach strip

Burlington’s heritage preservation has been hit and miss. Brant Street contains a few early buildings, such as the Queen’s Head and Raymond hotels. Halstead’s Inn, now a private home that stands at 2429 Lakeshore Road, may have been operating as early as 1830. And in 1979, a coalition of heritage-minded citizens managed to convince the council of the day to change its mind about demolishing a row of heritage homes along the lakeshore in favour of new development. Sadly, nothing remains of Burlington’s waterfront industries, but the area is now benefiting from a massive makeover that includes new walkways, breakwaters, and businesses.

Port Nelson

Situated at the foot of the Guelph Road, Port Nelson offered the backcountry farmers an outlet from which to ship their lumber and wheat. In 1851, William Smith described it as “a mere shipping place, containing about sixty inhabitants, doing but little other business. There are storehouses for storing grain for shipment, and a considerable quantity is exported.”3

The community was so named for being the port of shipment for Nelson Township (which, like Wellington Square, was named for a British war hero, Horatio Nelson.) The Guelph Line road linked the port to communities farther inland, such as the farm hamlet of Nelson on Dundas Street and the mill town of Lowville on Bronte Creek. It was not unusual during the height of the shipping season for grain carts and lumber wagons to line up along Guelph Line, awaiting their turn at the dock. During one busy season the little wharf handled more shipments than the much larger port of Hamilton.

Port Nelson also had lumberyards, saw- and planing mills. A small network of streets was laid out at the intersection of Guelph Line and the Lakeshore Road, comprising Market, St. Paul, 1st, and 2nd streets. Interspersed among the homes of the post-war era are a few older houses that date from the days when Port Nelson was a busy port.

A small lakeside park at the foot of Guelph Line does little to recall the times when the masts of tall ships would tower above the Port Nelson pier. There is no record of whether small piers stood at the foot of either Walkers Line or Appleby Line, although both roads were early farm roads that linked the lake with the farmlands to the north. As access to the lakeshore became easier with the arrival of the auto, wealthy business people began to buy up the shoreline and build some of the period’s grandest summer retreats.

East of Port Nelson stands one of the west coast’s grandest heritage homes, the “Paletta Mansion.” Whoever thought that “money couldn’t buy happiness” didn’t count on the wealth of Cyrus Albert Birge. It was Birge’s Hamilton foundry, the Canada Screw Company, that merged with four other companies in 1910 to form the mighty Stelco. Following his death, his wealth passed to his daughter, Edythe Merriam MacKay.

In 1930, on five and a half hectares at the mouth of Shoreacres Creek, Mrs. MacKay hired architects to design a grand stone mansion that would give her and her family the finest views of Lake Ontario that her father’s money could buy. The three-thousand-square-metre palace was designed by Stewart Thomas McFie and Lyon Sommerville. Other structures on the property include a 1912 gatehouse, a child’s dollhouse, and a stable. The dollhouse was not your average child’s toy either — it came equipped with both electricity and running water.

The mansion was restored by the City of Burlington in 2000 and can be rented from the city for conferences, banquets, and weddings. Now fully modernized, the three storeys still retain seven fireplaces and a grand staircase. A four-hectare “discovery trail” along the creek allows hikers the opportunity to observe birds and rare plant life. The gatehouse now contains a welcome centre and art studio, while the former stable is now the Tim Horton’s Learning Loft, offering youth camps and environmental programs.

The history of the property dates back more than two hundred years to the time when a grateful King George III granted the land to War of 1812 heroine Laura Secord.

Bronte

From the “Paletta Mansion,” Lakeshore Road traces an historic path, at times offering glimpses of the lake through small waterside parkettes, but for the most part cut off from those views by the endless rows of housing. The view opens up once more at the mouth of Twelve Mile Creek, where the port of Bronte developed.

The port was founded in 1834, and William Smith found Bronte a “stirring” little village in 1846 — one that contained grist- and sawmills, a store, and two taverns, and was home to about one hundred inhabitants. He made no mention of any port activity. Five years later he estimated the population as being about two hundred, and noted four sawmills along the creek. By this time the port had begun to develop, and in 1850 it shipped out six hundred thousand metres of lumber and over eighty thousand bushels of wheat, oats, and barley. More than two thousand cords of cordwood were picked up to fuel the lake steamers. The Bronte Harbour Company was formed in 1856, and shipping and boat-building began to dominate the harbour. Continuing the trend of Wellington Square and Port Nelson, the post office took the name Bronte in honour of Admiral Horatio Nelson, British war hero, and holder of the Duchy of Bronte.

With the arrival of the Great Western Railway in 1854, the port activity switched from exporting lumber and farm products to commercial fishing. From 1890 to 1950, more than a dozen fishing boats operated in the harbour, where the shore was lined with shanties and net-drying racks. With stonehooking4 a growing industry, the port also became home to a small fleet of stoneboats. One of the more prolific builders of the stonehookers was Lem Dorland, who between 1880 and 1885 launched five stonehooking schooners, including the Madeline, Rapid City, and Mapleleaf. By the 1950s, many of the commercial fishermen had moved away, and yachts began to take over the harbour.

Today’s urban growth has utterly altered the face of Bronte. Condos have replaced most of the historic storefronts, and new waterfront development has removed most traces of the historic port. Few heritage buildings have withstood the onslaught. One that remains is “Glendella,” built in 1845 as Thompson’s Hotel. It was originally constructed by Ned Thompson on what was called the Old Lake Road, and served for many years as a stagecoach stop. The arrival of the railway put an eventual end to stage travel in the area, and “Glendella” went on to serve as a grocery store and post office before resuming its role as a summer hotel. In 1987 the building was designated under the Heritage Act, but the act, as worded then, was utterly toothless, and twenty years later the building was threatened with demolition or removal to pave the way for still more condos. Luckily, an agreement was reached, allowing it, along with the old wooden police building and post office, to remain on site. The buildings will form a heritage square within the condo complex.

One of the other structures to survive is “Stoneboats.” Built in 1846 out of Dundas shale hauled from the lake, it was originally the home of one of Bronte’s prominent stoneboat captains. Today it is a restaurant.

On July 21, 2007, as part of the waterfront redevelopment, a fishermen’s memorial was unveiled. The granite stone, two metres high and four metres long, has laser etchings that depict images of a local fisherman named Thomas Joyce and smaller scenes from Bronte’s days as a busy fishing port. The new waterfront offers extensive walkways, a replica lighthouse, and a busy marina. On the west side of the harbour (a much more tranquil side) stands the Sovereign House. Built in 1825 by Charles Sovereign,5 it was relocated a short distance from its original site to a wooded promontory known as the Bronte Bluffs. The building, which was occupied briefly (1910–15) by Mazo de la Roche, author of the Jalna series of novels, is open to the public and offers period displays and travelling exhibits. Located at 7 West River Street, south of Lakeshore Road, it also houses the offices of the Bronte Historical Society.