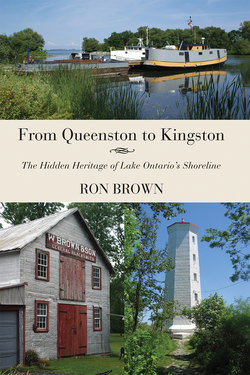

Читать книгу From Queenston to Kingston - Ron Brown - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroductionThe Shaping of the Lake

Lake Ontario’s shoreline is not old. In geological time it is but a newcomer. Exactly what the land looked like before the last ice age is anyone’s guess, but it was after the last great ice sheet finally trickled away that today’s lake began to take shape.

For about two hundred thousand years, massive glaciers moved back and forth over the land that is now Ontario, gouging gullies and depositing mounds of sand and gravel. As the ice began to melt, around twenty thousand years ago, the waters pooled behind the ice, creating lakes of varying shapes and levels. The earliest postglacial lakes formed to the western end of what is now Ontario, draining in a southwesterly direction. Later, as the ice continued to retreat northeast, the lakes found another outlet, and drained southerly through the Mohawk Valley of New York. At this time, the body of water that would one day become Lake Ontario, what geologists call Lake Iroquois, began to form. Due to the ice dam to the east, its level was much higher than Lake Ontario is today.

While at that level, the lake washed into glacial deposits, leaving behind a series of shore bluffs that today stand high and dry. As the ice sheet shifted from the east end of the lake, the water found a new outlet — down the St. Lawrence River — resulting in the lowering of the lake level. The land, suppressed from the weight of the ice sheet, remained low, and ocean waters moved into the area of today’s Brockville, bringing with them marine life. (The discovery of whale bones in these oceanic deposits gave rise to a myth of whales in Lake Ontario.)

When the ice left for good, the east end of the lake, now freed from that weight, rebounded, raising the levels at the western end of the lake and flooding existing river mouths. This inflow created lagoons along the shoreline that provided shelter for aboriginal villages, and later for the schooners and small boats of the early settlers. By then, Lake Ontario had assumed the configuration that it retains today — 311 kilometres long and eighty-five kilometres at its widest point. Of its nineteen thousand square kilometre surface area, more than ten thousand lie within Ontario, as does most of its 1,146 kilometres of shoreline.

When the ice melted, arctic flora and fauna flourished, creating a tundra-like landscape and paving the way for early aboriginal populations. Archaeologists have labelled these peoples as “fluted point” for the shape of their spearheads. These artifacts and a few burial mounds such as the Serpent Mounds on Rice Lake and the Taber Hill Mound in Scarborough constitute the scanty physical evidence that remains of those early populations.

Lagoons that formed the lake’s early harbours were a result of rising lake levels caused by the melting of the glaciers more than ten thousand years ago.

Human migration continued, and by the time the first Europeans arrived, the land north of Lake Ontario was inhabited primarily by the Huron people. The first Europeans had come looking for China, the land of silk and gold. In fact, Samuel de Champlain, when he first portaged his way up the rapids of the St. Lawrence in 1608, called them the “Lachine” Rapids, French for “China.” Guided by members of the Algonquian First Nation, he followed the traditional aboriginal route into the Great Lakes, up the Ottawa, across Lake Nipissing, and down the French River into Georgian Bay. Convinced he had at last arrived at the Pacific Ocean, he called it a mer or “sea.” But the absence of salt meant it was not the ocean he was seeking. Again, guided by his Algonquian friends, Champlain’s group made their way into Lake Simcoe, which he called Lac Taronto, and then followed the Kawartha and Trent River System into the Bay of Quinte. From here he crossed the lake to help his allies attack a Seneca village on the south shore of Lake Ontario, only to suffer a defeat that exacerbated the animosity between the Iroquois and the Algonquian.

When the French finally realized they were a long way from the riches of the Orient, they settled for fur, as well as trying to convert the indigenous inhabitants to Catholicism. Missions were established, such as the one on Georgian Bay, known today as Sainte-Marie among the Hurons, and Kente, on the Bay of Quinte. It was at Saint-Marie that the culmination of Iroquois incursions into Ontario in 1648 resulted in the deaths of Fathers Brébeuf and Lalemant and the near eradication of the Huron and the Neutrals.1

By 1670, six Native villages were in place along the lake’s north shore, including Ganestiquiagon, a Seneca village at the mouth of the Rouge River; Ganaraske, a Seneca site at the mouth of the Ganaraska River; and Quintio, at the neck of the Prince Edward Peninsula. Near Napanee stood the Oneida village of Ganneious.2 With the bulk of the Iroquois still south of the lake, these villages were small, and after 1701, when the French and Iroquois concluded a peace treaty, were abandoned. Once the Iroquois had left, an Algonquian group known as the Mississauga moved in along the lake from their lands north of Georgian Bay. Although their home territory remained farther north, they used the lakeshore primarily as seasonal hunting and fishing camps.

For the next half century, the French maintained a series of forts along the lake, largely as fur-trading outposts, though they were garrisoned to guard against the British, whose territory lay along the lake’s south shore. By 1758 the French had abandoned their outposts, and in 1763 the Lake Ontario shore became British.3

Twenty years would pass before full-scale migration swamped the lake. In 1783, Britain’s American colonies had won their independence and did not take kindly to those who had chosen to remain loyal to the British. These Loyalists were beaten, killed, or at the very least lost their property. To help resettle those who survived, by then officially called United Empire Loyalists, the British government laid out a series of townships, primarily at the east end of Lake Ontario and in the Niagara area, in which to disseminate free land as well as grain seed and farm utensils. During 1783–84, the government concluded agreements that would allow Loyalist settlements between Montreal and Trenton.

The ruins of the early French fort, Fort Frontenac, have been unearthed in downtown Kingston.

After the first influx tapered off, more followed, taking up the shoreline between Trenton and Toronto. Upper Canada’s first lieutenant governor, John Graves Simcoe, arrived in 1792 and relocated the legislative capital from Newark (now Niagara-on-the-Lake) to what is now Toronto Harbour and named the site York. Further treaties with the Mississauga between 1787 and 1805 freed up more land for settlement between Trenton and Toronto. Meanwhile, the Mohawk followers of Joseph Brant took up territory along the Grand River and on the north shore of the Bay of Quinte, between today’s Shannonville and Deseronto, today the Tyendinaga First Nation Territory. Although the Missisauga retained some small areas along Lake Ontario for fishing, the bulk of their population wound up on reserves in the Rice Lake and Kawartha Lakes areas, as well as on a parcel near Brant’s Six Nations settlement on the Grand River.

To provide the new arrivals with a steady supply of building materials, the government ordered sawmills to be built at Kingston and on the Humber and Don rivers at York. Industry gradually took hold as gristmills appeared, as well. Wharves were built into the lake to ship grain and lumber, as often as not by the individuals who just happened to own that shoreline. Fishing at the time was very much an individual occupation, and usually consisted of lakeshore farmers setting nets close to shore to provide for their needs and those of their neighbours. As more migrants arrived, more industry developed. Distilleries were constructed in conjunction with the gristmills. Ontario’s first steamboat, the Frontenac, was launched at Finkle’s Tavern in Ernestown (now Bath) as was its first brewery. Steamboats appeared and gradually replaced the wind-powered schooners, giving the larger harbours an advantage over the little coves and lagoons. Towns selected as district and later county administrative seats grew larger.

Still, transportation remained difficult. Lake travel was seasonal, while roads were usually muddy quagmires. Simcoe opened roads to Lake Simcoe and the Thames River in the 1790s while Asa Danforth gamely carved out a winding road from York to the Bay of Quinte. His trail proved to be poorly located and unpopular with settlers, and was replaced with a straighter Kingston Road in 1817. Still, stage travel between Kingston and York could take anywhere from three to five days.

Much changed with the arrival of the railways. While such projects had been proposed as early as the 1830s for Hamilton and Cobourg, the first steam-powered rail operation did not commence until the early 1850s. The Grand Trunk Railway (GTR) and Great Western Railway (GWR) followed the shore of the lake, while resource lines like the Cobourg and Peterborough, the Central Ontario, the Kingston and Pembroke, the Bay of Quinte, and the Midland railways tapped into the hinterland. Communities that acquired a rail link added foundries and factories to their roster of industries. By this time the lumber industry was losing its supply of logs, but farming and fishing became more specialized.

Canals also altered the industrial landscape: the Desjardins Canal linking the lake with Dundas opened in 1837; the Welland Canal linking Port Dalhousie with Lake Erie opened in 1828; the Rideau Canal opened between Bytown and Kingston in 1832; and the Murray Canal connected the Bay of Quinte with Wellers Bay in 1889. Locks were improved along the St. Lawrence, permitting ever larger vessels to enter the lake, and forcing many small ports to close. During the Prohibition era of the 1920s, many of these hidden coves returned to life, as fishermen made their late-night runs, carrying boatloads of whisky and beer to the thirsty Americans.

As cities and towns grew, so did the workforce. Seeking respite from their smoky urban environs, city dwellers sought out bucolic lakeside retreats, even if just for the day, and the tourist boom was underway. Beaches and waterfronts soon became the haunt of amusement parks, pleasure grounds, and “casinos” or dance halls. Places like Port Dalhousie and Hamilton Beach, along with Sunnyside, Hanlan’s Point, and The Beach in Toronto, all hosted major amusement parks, while smaller grounds were common nearly everywhere.

By this time, the many sturdy forts that protected Ontario against possible American attacks had either been downgraded or had fallen into outright ruin. Some were rebuilt or restored as Depression-era make-work projects, while Fort Henry and Fort York housed prisoners of war during the Second World War. The end of that conflict ushered in the auto age, one that would once more transform the towns and cities along the shore. In addition to the shoreline railways, there were now high-speed highways, with the Queen Elizabeth Way becoming North America’s first limited-access freeway in 1939. By 1955, the Toronto Bypass was on its way to becoming the 401, and piece by piece connected Toronto with Kingston and beyond.

As railways changed from coal to diesel, the coal boats no longer called, and tracks were lifted from most of the lake’s port lands. Kingston, Deseronto, Belleville, Trenton, Cobourg, Port Hope, and Whitby all lost their rail links to the lake. New industries preferred truck-friendly locations by the highway and away from the antiquated harbour sites. The fishing industry all but vanished, with only a handful of fishing boats still operating in the Prince Edward County area. Many municipalities were pondering the fate of their waterfronts, and several undertook major overhauls, ripping up old wharves and replacing them with marinas. Warehouses and grain elevators made way for hotels and condominiums — Kingston and Toronto being the main culprits here. In many locations, public access was restored and rebuilt, allowing for a renewed era of waterside recreation. Cobourg, Hamilton, Toronto (despite its wall of condos), and Burlington are prime examples of such concerted efforts. Others, such as Port Darlington and Deseronto, await their turn.

Despite the waves of sweeping change that have altered the Lake Ontario shore, its heritage lingers today; some well-known and heavily promoted, some known to only a few. In these pages, I hope to open a modern-day window on the evidence of Lake Ontario’s hidden heritage, all the way from Queenston to Kingston.