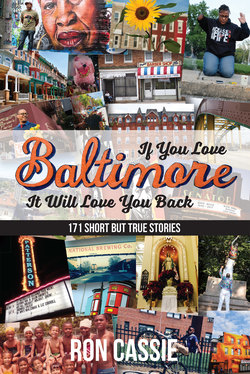

Читать книгу If You Love Baltimore, It Will Love You Back - Ron Cassie - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеMiddle East

McElderry Park

May 19, 2009

2. Old Heads

At dusk in the 3100 block of McElderry Street in East Baltimore, Dante Barksdale grabs a bullhorn. In baggie shorts and work boots, a hoodie pulled over his shaved head, Barksdale, whose very name is associated with violence in the city (courtesy of the HBO series The Wire), strides into the intersection of McElderry and North Robinson streets, stopping traffic.

Forty-eight hours earlier, a young man was shot on this corner.

Barksdale addresses everyone within earshot: the women looking on from their front stoops, a group of older men standing near a car, store owners peeking outside, and his target audience—the teenagers and twentysomethings in white T-shirts milling about. His demeanor is deadly serious; his voice is filled with urgency. “Life is precious,” Barksdale shouts. “Let’s not make funerals a part of our lives. Everybody has a purpose. We want the streets to be safe.”

The cadence of his speech becomes rhythmic, almost poetic: This is not a jungle, this is our home/We have to live in harmony, not carry guns/Stop the shooting, stop the killing.

Now in his mid-30s, Barksdale bounced around dock and construction jobs after serving a 10-year prison sentence for heroin and cocaine distribution. For the past 18 months, he’s been a full-time outreach worker with Safe Streets, an innovative two-year-old City Health Department initiative aimed at reducing the leading cause of death among males aged 15 to 34 in Baltimore City: homicide.

Barksdale leads a march around the block, with a gathering group of community activists, outreach workers, neighbors, and youngsters in tow. “Put away the guns,” he implores. “Put away the guns. ”

Modeled after Chicago’s CeaseFire, a program credited with substantially reducing shootings and homicides in the roughest Windy City neighborhoods, Safe Streets hires ex-offenders who are turning their lives around and trains them as mediators and outreach workers. They work in the same streets they once ran, establishing relationships with men and women considered at high risk of getting shot—or shooting others.

“We cut through all the bull crap and put the light on all the bad stuff,” says Barksdale. “[We] tell them the truth. Like prison: no air conditioning, no girls, and you’re under a whole lot of pressure in jail, dog. I tell them, ‘They steal your peace of mind in there.’”

He goes on: “They’re thinking, ‘I can get a pack [of coke], get rid of that in five days, and then I can get me some clothes.’ The only thing is, you might not be alive when that pack is done. Seven grams of cocaine, maybe you make $500 or $600, but before you finish it, you might have a bail of $50,000. I wake them up.”

Barksdale says many of the friends he grew up with are dead or in prison. Both facts haunt him, as that cycle continues. “I don’t like it when I see the same things happening,» he says. “I didn›t like it even when I was a part of it. But this is still my neighborhood, and that›s my motivation. I want to make my mother proud today, allow her to hold her head up. Maybe I can help save someone.»

His first night canvassing, Barksdale spotted about 16 young men standing in the middle of a street, blocking a Lincoln Town Car. In what was a potentially violent standoff, two guys had stepped outside the car and one remained inside. Barksdale recognized a few of the participants.

“I’m thinking, ‘This doesn’t look right,’” he recalls. “But I keep walking up. I keep walking and I’m smiling—I am not afraid of nothing—I mean, I grew up on these same streets. And I’m handing out Safe Streets literature, telling everyone I’m from Safe Streets and asking, ‘What’s going on here?’”

One of the two guys standing by the car told him it’s about, “What this girl said.”

“What this girl said? ” Barksdale asked. Then, he laughed at the