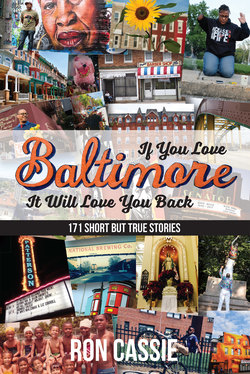

Читать книгу If You Love Baltimore, It Will Love You Back - Ron Cassie - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCatonsville

South Rolling Road

June 1, 2009

3. Breaking the Habit

Gloria Carpeneto was born as she puts it, “to a ritually-correct and card-carrying Roman Catholic” lower middle-class European immigrant family. Baptized four days later, Sept. 14, 1947, at St. Anthony of Padua in northeast Baltimore, she attended the parish grade school with four brothers and sisters and graduated from the all-girls Seton High School on Charles Street at a time when students were “still wearing nurses uniforms,” she recalls with a laugh.

When she accepted a vocation with the Sisters of the Good Shepherd in Peekskill, NY, it surprised her family. Not because she was becoming a nun, but because she was leaving Baltimore and moving to New York.

“As you much as you can, at 17 years old, hear a call from God, I did,” Carpeneto says. “The Sisters of the Good Shepherd worked primarily with women, victims of domestic abuse, and ‘delinquent’ girls. They were out in the world, and that was very attractive to me. Even as a teenager, I really liked social service work.”

But after two years, Carpeneto, then sister Gloria Ray, questioned if the ordered life was a good fit. “It was the way convents were organized at the time, the structure. I wasn’t happy with the system. It really pushed me back home.” By no means did she ever question her faith.

Her first job upon return was in the Chancery office of the Archdiocese of Baltimore and Lawrence Cardinal Shehan. In the evenings, she finished the undergraduate work she’d begun at New York’s Fordham University at another Jesuit institution, Loyola College.

“I didn’t question Church doctrine then, not the role of women in the church or anything,” she says. “Not like today when we talk about the ‘stained glass ceiling.’”

Indeed, she could not have imagined, 40 years after departing the convent, she’d hear a new religious calling, leading to ordination as a priest—as well as ex-communication by the Vatican.

Last summer, the petite, gray-haired, 61-year-old grandmother took part in a ceremony in Boston with two other women and claimed holy Orders as a Catholic priest. Several hundred supporters attended the July ordination, which the Archdiocese of Boston immediately denounced.

Despite facing ex-communication, Roman Catholic Womenspriests have ordained 35 female priests, seven deacons and one bishop in the U.S. since 2002. In Canada and Europe, where the movement began, they have ordained another 20 bishops, priests, and deacons, all in accordance with historic apostolic tradition, they maintain.

Together with Annapolis resident Andrea Johnson, who claimed Catholic priesthood in 2007 in a similar ceremony, Carpeneto leads Mass—outside the auspices of Archdiocese of Baltimore—on the third Sunday of every month at a Protestant church in Catonsville. Typically, 30 to 40 people, including men, women and families, attend services, and Carpeneto estimated 100 supporters receive their e-mail updates.

Some people have asked her why she and the other women didn’t just leave the official Roman Catholic Church and, for example, join the Episcopalian Church or another mainline Protestant denomination that ordains women to fulfill her calling.

“The simple answer of why I didn’t choose to leave the Catholic Church is that I’ve been a Roman Catholic since I was four days old. It’s not just my religion, it’s my culture, like Judaism is for Jewish people,” Carpeneto says. “All of us [in the women’s ordination movement] love the Roman Catholic Church and our choice is to reform from within rather than walk away.

“We’ve all said this is our family.”