Читать книгу Chinese Houses of Southeast Asia - Ronald G. Knapp - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

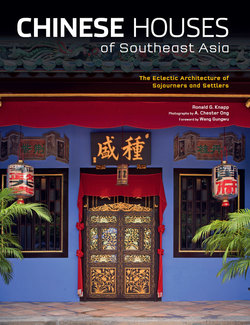

ОглавлениеTAN CHENG LOCK RESIDENCE

MALACCA, MALAYSIA

Late 1700s with subsequent changes

One residence along Malacca’s Heeren Street, today renamed Jalan Tun Tan Cheng Lock, provides an opportunity to unravel on a different scale some of the many layers of history and culture that have enlivened Malacca over the past three centuries. Tan Cheng Lock, a fifth-generation descendant of an eighteenth-century immigrant from China and a distinguished twentieth-century statesman whose leadership led to the establishment of an independent Malaysia upon the departure of the British, was born in 1883 at No. 59 Heeren Street. This residence had been acquired in 1875 by his grandfather, Tan Choon Bock, who willed it on his death in 1880 to Tan Keong Ann, his son and Tan Cheng Lock’s father. No reason is given in the grandfather’s will as to why the house was granted to the third son rather than his elder brother. In the preceding eight decades, the residence had passed through numerous hands before coming into the ownership of the Tan family, who have continued to maintain it for nearly a century and a half since then as their “ancestral” home. Today, the residence, renumbered No. 111, is important not only for its age and layered provenance but also for its historic association with an important man and his family.

Surviving probate records show that there was already a residence on this site in 1797, and extant title deeds, which are remarkable in their detail, trace each of the transfers during the nineteenth century. In 1801 the widow of Daniel Roetenbeek, Silviana de Graca, inherited the property upon his death, and then in 1804 gave the property to her son-in-law, Johann Anton Neubronner, a German, whose widow then inherited the property in 1815. It was owned by the Neubronner family until 1849 when the home was bought at auction by a Chinese named Yeo Hood In, a Malacca-born property owner then living in Singapore. The house was then resold in 1864 to Tan Loh Seng. In 1875, as mentioned above, the property was purchased by Tan Choon Bock, who had become quite wealthy as a pioneer in the tapioca and gambier business as well as being the founder of a major steamship company.

This date, 1875, is fully a hundred years after the arrival of Tan Hay Kwan, an immigrant from Nanjing county in Zhangzhou prefecture near the port of Xiamen in Fujian province, who is the progenitor of the lineage that was to produce Tan Cheng Lock. As a trader with his own junk who followed the alternating seasonal winds of the monsoon from his base in Malacca, Tan Hay Kwan’s commercial activity ranged widely, to Makassar in the Celebes, Bandjarmasin in Borneo, Rhio at the tip of the Malay Peninsula, nearby Penang and distant Australia, as well as the southeast coast of China (Agnes Tan Kim Lwi, 2006: 2; Tan Siok Choo, 1981: 20). Nothing is known of Tan Hay Kwan’s residence in Malacca or elsewhere, nor that of his son, nor even the home or homes that Tan Choon Bock lived in before 1875 when he purchased the late eighteenth-century property we now regard as the family’s ancestral home. Indeed, throughout the nineteenth century, affluent Peranakans, the offspring of Chinese and indigenous marriages, as well as recent arrivals from China who had the financial wherewithal, purchased many of the old Dutch merchant residences in Kampung Belanda (Dutch Village), thus transforming the area into a veritable Chinatown that has endured to the present day. There are no formal records of what renovation or rebuilding took place over these decades along the streets of the old Dutch town. Physical evidence, however, provides proof that some houses were merged and expanded. Others were modified in one way or other to accommodate family and commercial needs as well as carriages and horses.

The Tan Cheng Lock residence shares an architectural style with a building on its left. Both were built at the same time and were likely originally owned by a single family, who later sold the units to different families.

A close-up of the painting above the altar showing General Guan Gong, who is said to personify many virtues—courage, honor, integrity, justice, loyalty, and strength—and Zhang Fei, another loyal warrior and his comrade of the Three Kingdoms period.

Those writing about the old residences in Malacca sometimes point to purported Dutch architectural influences, perhaps to provide incontrovertible “proof ” of Dutch origins and dates for buildings. These include the use of iron wall-anchors, archways, stone corbels, fired bricks and roof tiles, recessed cupboards, even steep staircases (De Witt, 2007: 145–9). While Dutch building traditions very well may have employed them, most of these architectural elements also have been a part of the repertoire of building practices in southern China, not only with residences but also with temples and palaces. Traditional masons and carpenters in China and those who migrated, as with vernacular builders elsewhere in the world, were fundamentally pragmatists who would alter their materials and methods to meet local conditions. In Malacca, it is certain that the inherited building conventions brought from the varied homelands of immigrants, including Dutch and Chinese, were adapted to local conditions, factors that were facilitated by the overlap of common ways of doing things. Moreover, as wealthy Chinese acquired older homes once occupied by the Dutch and other Europeans, they frequently employed craftsmen from China to make modifications that expressed not only the practical needs of the Chinese occupants but also to embellish them with the types of calligraphic and pictographic ornamentation found in finer homes in China. In addition, Peranakan culture thrived in the fine residences along Heeren Street as the Victorian era came to an end, a time when new layers began to be added to the homes that not long before had been dressed in Chinese adornment. Now, floor and wall tiles imported from England, mirrors and glass from Italy, prints and objets d’art from throughout Europe, and furniture of many styles, including the increasingly popular Peranakan brown-and-gold carved teak furniture gilded in gold leaf, which was made locally rather than imported, were added. Even as these changes in the material culture of the residences were taking place, the observance of Chinese rituals continued during annual celebrations such as the New Year and the festivals related to rituals for the dead, such as Qingming (Clear and Bright) on the fifteenth day after the vernal equinox, and Zhongyuan (Hungry Ghost Festival) on the fifteenth day of the seventh lunar month.

Dominating the entrance hall is an altar table with images of various deities as well as a painting of Guan Gong and Zhang Fei. The characters yiqi above the altar translate as “righteousness.”

The spacious vestibule-like sitting room is just beyond the entrance hall. While the tables and chairs in this room are Western in style, the wall decorations are all Chinese. The embroidered wall hanging with figures representing the Three Stellar Gods, Fu, Lu, and Shou—Good Fortune, Emolument, and Longevity—was given to Tan Cheng Lock’s son, Tan Siew Sin, on the occasion of a birthday.

On the right is one of a pair of lattice windows that act as a screen filtering the view through the doors from the entrance hall into the interior. Circular stairs to the second floor rise within the alcove.

An assemblage of deities on the altar table.

Punctured by a rectangular skywell, a shaft that reaches up through the second storey, this bright space is filled with pots of ornamental palms of various sizes. The elongated wall is covered with historic photographs and horizontal commendation plaques.

Isabella Bird, the noted Victorian globetrotter who visited Malacca in the late 1870s, caught glimpses of the rising prominence of Chinese families, a milieu that Tan Cheng Lock was born into (1883: 133):

And it is not, as elsewhere, that they come, make money, and then return to settle in China, but they come here with their wives and families, buy or build these handsome houses, as well as large bungalows in the neighbouring coco-groves, own most of the plantations up the country, and have obtained the finest site on the hill behind the town for their stately tombs. Every afternoon their carriages roll out into the country, conveying them to their substantial bungalows to smoke and gamble. They have fabulous riches in diamonds, pearls, sapphires, rubies, and emeralds. They love Malacca, and take a pride in beautifying it. They have fashioned their dwellings upon the model of those in Canton, but whereas cogent reasons compel the rich Chinaman at home to conceal the evidences of his wealth, he glories in displaying it under the security of British rule. The upper class of the Chinese merchants live in immense houses within walled gardens. The wives of all are secluded, and inhabit the back regions and have no share in the remarkably “good time” which the men seem to have.

“Many of the women who lived there vied with each other for the distinction of having the finest set of jewellery, the most exquisite clothes, the best nyonya ware, and the most magnificent furniture. They also tried to out-do each other in culinary skills and beadwork—both attributes for every nyonya girl” (Tan Siok Choo, 1983: 51). Today, visitors to Malacca can experience this culture by visiting the private Baba-Nyonya Heritage Museum outfitted in an adjacent pair of nineteenth-century terrace houses. Once homes of prominent families, some properties have been refashioned as boutique hotels—Hotel Puri and Baba House Hotel—where visitors can experience the richness of Peranakan culture. Along the street is a smaller but well-restored old terrace house that has been elegantly transformed into a bed-and-breakfast called The Snail House.

Tan Cheng Lock, the Man

Tan Cheng Lock is best known in Malaysia as a statesman because of the prominent role he played with other political leaders such as Tunku Abdul Rahman and V. T. Sambanthan in negotiating independence from the British, his promotion of Malaysia as a multiethnic state, and as the founder and first president of the Malayan Chinese Association. The Tan ancestral home was the venue for much discussion about issues relating to obtaining independence from the British.

A true son of Malacca, Tan attended Malacca High School, an English-medium institution established in 1826 after the Dutch ceded the city to the British, before furthering his education at the Raffles Institution Singapore. After graduating, even before turning twenty, he was invited to stay on and teach young boys at the Raffles Institution. As one of the few Chinese in the Straits Settlements with a Cambridge School Certificate, he was a voracious reader of European literature, philosophy, and history, as well as translations into English of books about Chinese culture. Although he taught at Raffles Institution from 1902 to 1908, “he was out of his depth teaching unruly schoolboys,” according to his daughter Agnes, and was urged by his mother to look for a future in rubber, a crop and industry that in time was to flourish in British Malaya (Agnes Tan Kim Lwi, 2006: 2). With the help of his cousin as well as close friend and businessman, Chan Kang Swi, Tan Cheng Lock created several firms that ran labor-intensive plantations of the Hevea brasiliensis or rubber tree, which produced the seemingly magical elastic latex called “rubber.” Commercial planting of rubber trees had only begun in the Malay States in 1895, with soaring expansion of acreage between 1905 and 1911 to meet increasingly robust world markets, just when Tan Cheng Lock was seeking a new challenge. The United Malacca Rubber Estates, which was established in 1910, brought him some prominence, and he was appointed in 1912 as a member of the Malacca Municipal Council by the British authorities. In time, his involvement in social issues ranged from condemning the use of opium, a major source of revenue for the British in Asia, and countering the common Chinese practice of polygamy by encouraging monogamous marriages.

Tan Cheng Lock’s study is aligned along a wall adjacent to the skywell, with a plaque proclaiming “Honor Results from Actual Achievements.”

An elaborate ornamental lattice screen runs from wall to wall between the skywell and the ancestral hall.

In 1913, at the age of thirty, Tan Cheng Lock married Yeo Yeok Neo, an heiress whose father had arranged the union. Tan Cheng Lock and his wife had five children, a son and four daughters. Tan Siew Sin, Tan Cheng Lock’s only son, who was born in the Heeren Street family home in 1916, also became a distinguished public servant, serving as Malaya’s first Minister of Commerce and Industry before becoming Malaysia’s first Minister of Finance from 1959 to 1974. Four daughters, Lily (Tan Kim Tin), Nellie (Wee Geok Kim), Alice (Tan Kim Yoke), and Agnes (Tan Kim Lwi), were born into the household. Tan Cheng Lock’s attention to the teachings of Confucius is well known, especially the emphasis on the filial duty of remembering ancestors through periodic ritual. Even with Tan Cheng Lock’s business and political careers underway, according to his granddaughter, he was “relieved of the necessity of having to earn money in less salubrious ways,... [and] set about increasing his wife’s inheritance” (Tan Siok Choo, 1981: 24). Because of his civic activity, he was appointed an unofficial member of the Legislative Council of the Straits Settlements in 1926, and in 1933 a member of the Executive Council of that body.

Lee Seck Bin, Tan Cheng Lock’s mother, who recognized her son’s unhappiness as a teacher and urged him to consider venturing into the rubber business where he thrived.

Late nineteenth-century photograph of Tan Keong Ann, Tan Cheng Lock’s father, who is shown here wearing a mixture of clothing, including a Chinese-style jacket, a Western-style fedora and leather shoes.

Wearing Malay attire, Tan Cheng Lock is standing with his only son and three daughters.

With a three-character board above it proclaiming “Hall of Filiality,” the Tan family ancestral altar holds the ancestral tablets of three generations, including Tan Cheng Lock and his wife, Tan’s parents and their son, Tan Siew Sin. Above the altar is the ancestral portrait of Lee Chye Neo, the wife of the progenitor Tan Hay Kwan. On the left wall are images of Tan Cheng Lock’s grandparents. The furniture, brought from Hong Kong on the occasion of daughter Lily’s wedding in 1935, is a mixture of traditional Chinese forms with Western elements.

Tan Cheng Lock, the Residence

The Tan Cheng Lock ancestral residence is a notable structure replete with furnishings, ornamentation, and memorabilia that declare his appreciation and understanding of the several cultures within which he lived. Although Tan Cheng Lock could neither speak nor read the Chinese language, his home celebrates the power of the written word in Chinese culture and gives evidence of the high regard in which the Chinese community in pre-and post-independence Malaysia held him. The ground plan of his residence, approximately 10 meters by 68 meters, is similar to those of other larger houses along the seaside section of Heeren Street. Set back from the street, the two-storey façade is separated by a shed-like roof that creates a streetside veranda paved with large terracotta tiles, a passageway known as a five-foot way and a requirement imposed by British planners. This type of setback with a veranda is not common in China. Just inside the double-paneled entryway is an entrance hall dominated by a high rectangular altar table accompanied by a square offerings table. Both of these are set in the central portion of a wall that has doorways on both sides. Formal sets of chairs and tables line the walls. Couplets and auspicious four-character phrases adorn the room. The two-character phrase yiqi, meaning “Righteousness,” is hung just below the ceiling and above an old painting of the Daoist deity General Guan Gong, also known as Guan Yu, who is said to personify many virtues—courage, honor, integrity, justice, loyalty, and strength—and Zhang Fei, another loyal warrior and his comrade of the Three Kingdoms period. A wooden panel on a stand has images of all Three Brothers of the Peach Orchard, Guan Gong, Zhang Fei, and Liu Bei, who were celebrated in the Romance of the Three Kingdoms as individuals who shared a desire to serve their country in difficult times. Two large paintings and calligraphic hangings, which face each other across the room, add both formality and brightness to the space.

Pastel portraits of Tan Cheng Lock’s parents, Tan Keong Ann and Lee Seck Bin, are given pride of place along this wall. The settee, which is constructed of hongmu, known in English as black-wood, has three marble inserts in the shape of peaches, emblems of longevity.

Looking up in the second skywell, one sees wooden louvered shutters with an ornamental panel beneath comprising linked wan characters that also symbolize longevity.

Just beyond the doors is a spacious vestibule-like sitting room with a round marble-topped table. While the furniture in this room is Western in style, the wall decorations are all Chinese. Of particular note is a large celebratory piece of embroidery that was given to Tan Cheng Lock’s only son, Tan Siew Sin, on the occasion of one of his birthdays. At the center of the piece and along the top are figures representing the Three Stellar Gods, Fu, Lu, and Shou—Good Fortune, Emolument, and Longevity—together with an unidentified woman, perhaps an attendant. Arrayed along the sides are the Eight Immortals.

A pair of beautiful lattice windows acts as a screen filtering the view through the doors from the entrance hall into the interior areas. A central door then leads from the sitting room into an elongated room punctured by a rectangular skywell, a shaft that reaches up through the second storey. This bright space is today filled with pots of ornamental palms of various sizes. An informal setting of a table with four light chairs contrasts with the rows of formal hardwood chairs that stand along the walls. Throughout this area the walls are covered with historic photographs and horizontal commendation plaques. On the right, tucked into an alcove and reached through an archway, is a spiral staircase leading to the second level. A study with a desk and bookcases filled with classic texts is aligned along a wall adjacent to the skywell. Above the desk is a commendation plaque presented to Tan Cheng Lock proclaiming “Honor Results from Actual Achievements.” A fine example of a Milners Patented Fire Resisting safe stands beside the desk. On top of the safe is a signed photograph presented by Chiang Kai-shek to Tan Cheng Lock in 1940, which is propped up by a bust of Robert Baden-Powell, the founder of the Boy Scout movement in 1907.

Just beyond the first skywell is an ornamental lattice screen running from wall to wall that frames a sitting room dominated by the Tan family ancestral altar with three characters, xiaosi tang, meaning Hall of Filiality, on a horizontal board above it. The three ancestral tablets, also called ancestral soul tablets, within the receptacle are those of Tan Keong Ann and his wife Lee Sek Bin; the ancestral soul tablet of Tan Cheng Lock and his wife Yeo Yeok Neo, and at the lowest level, the ancestral soul tablet of Tan Siew Sin. Above the altar is the ancestral portrait of Lee Chye Neo, the wife of the progenitor Tan Hay Kwan. On the left wall are images of Tan Cheng Lock’s grandparents, Tan Choon Bock and Thung Soon Neo, in frames with oval mounts, while on the right wall are pastel portraits of Tan Cheng Lock’s parents, Tan Keong Ann and Lee Seck Bin. The furniture in this room, which mixes traditional Chinese forms with Western elements, includes low-back armchairs and settees made of hongmu with marble inserts. The furniture was brought from Hong Kong on the occasion of daughter Lily’s wedding in 1935. Each of the settees has three marble inserts in the shape of a peach, a symbol of longevity. On the side walls, each with an elaborate framed mirror and among the photographs of family members are paintings and four horizontal commendation plaques presented to Tan Siew Sin with celebratory phrases: “Benefit the Country and Workers,” “Carrying a Heavy Responsibility Over a Long Period,” “Pillar of the Nation,” and “Merit is in Educating the Young.”

The master bedroom facing the street has circular ventilation ports along the top register of the wall. The Art Deco furniture was purchased in London for the marriage of Tan Cheng Lock’s daughter Lily in 1935.

Prior to the Second World War, the formal space housing the ancestral soul tablets marked the boundary between the public and private areas of the residence. Non-family members rarely were permitted to go beyond the formal halls and single skywell in the residence. The doorway on the left side of the altar leads to a small bedroom, which was created by adding a wall to a wider open area, which then became a narrower passageway. Within this small room is a cupboard that is identical to one along the wall of the passageway on the right. Beyond this passageway are the two remaining skywells, spaces for family dining and informality. In these areas, as with the other skywell in the front, it was possible also to capture and store rainwater. While most houses on Heeren Street in the past had two wells, the Tan household only had one and that was located in a bathroom. Both of the skywells today are landscaped with abundant greenery. Looking up, one sees the louvered windows that can be opened on the second level. Just below the louvered panels is a geometric ornamental panel with duplicated representations of the running wan character, an inverted swastika meaning “longevity.” Two bathrooms, a pantry, and a kitchen are also found in this area in addition to a steep staircase leading upstairs. In a circular masonry planter in the third skywell is a tall jambu tree with evergreen leaves that produces a red bell-shaped edible fruit called lianwu in Chinese and wax apple in English. Family lore recalls that this thriving and productive tree was planted when Tan Cheng Lock was born. At the far rear end of the house is a second dining area and a terrace, which early on had been the place where children ate. In recent years, this space was renovated as a two-level apartment for a housekeeper and her children. When the residence was built early in the nineteenth century, this rear area extended out over the sea below and was supported by pilings. A trapdoor in the wooden floorboards could be lifted for reaching a small boat moored below. In the nineteenth century, the area began to be silted up and in recent decades infilling was accelerated that pushed the shoreline some 200 meters away from the old houses.

The upstairs area covers fully two-thirds of the ground floor, with two of the skywells opening up the rooms on that level as well. This private area has two large bedrooms with adjacent sitting rooms. Until Tan Cheng Lock’s daughter Lily was married in April 1935, the front bedroom had been the bedroom of his younger brother, Cheng Juay and his wife. In preparation for the marriage, fashionable new furniture for the bridal chamber was brought from London via Singapore.

The second floor sitting room showing a doorway into the bedroom. Above each window is a painting of a fruit with symbolic associations: on the left is an odd fruit called foshou or “Buddha’s Hand,” whose names is homophonous with good fortune and longevity; on the right is a pomegranate with its red seeds exposed that expresses the meaning of abundant posterity.

Unlike Chinese custom where the daughter-in-law generally married in to the home of her husband, Tan Cheng Lock and his wife Yeo Teok Neo chose to follow local Baba custom of matrilocal residence and live with her mother, Yeo Tin Hye, in Tranquerah. This continued even after the birth of their eldest daughter Lily. Their son Siew Sin and daughters Alice and Agnes, however, lived at the ancestral residence on Heeren Street with their grandparents, Tan Keong Ann and Lee Seck Bin, as well as with Cheng Juay, Tan Cheng Lock’s younger brother and his wife. Nellie, the second daughter, was adopted at birth by Tan Cheng Lock’s sister, who was childless. Living arrangements such as this met practical considerations and revealed the strength and flexibility of an extended family. Meanwhile, Lee Seck Bin, the matriarch, urged her husband to find a larger house that all could live in. Such a house was found six kilometers north of Heeren Street in Klebang Besar facing the Strait of Malacca. After 1947, when Tan Siew Sin married Catherine Lim Cheng Neo, this became the home in which he raised his three daughters. Today, along Jalan Klebang bordering the sea one can still see some of the large mansions built by prominent Peranakan families at the turn of the twentieth century.

Portrait of Tan Choon Bock, Tan Cheng Lock’s grandfather.