Читать книгу Chinese Houses of Southeast Asia - Ronald G. Knapp - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

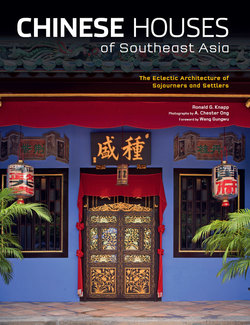

ОглавлениеThe streetside entry to the Kee Ancestral manor, Sungai Bakap, Malaysia, in the early twentieth century.

THE ARCHITECTURE OF SOJOURNERS AND SETTLERS

Migration has been a recurring theme throughout Chinese history, continuing to the present at significant levels. The dynamic relationship among push and pull factors has long motivated both the destitute as well as the adventurous in China’s villages and towns to uproot themselves in order to move to locations within China and throughout the world in search of opportunities. Settling on a new place to live by building a home, which Chinese called dingju, has always resulted from a complex combination of individual resolve, cultural awareness, and financial resources. Chinese Houses of Southeast Asia examines the products of these decisions and actions, the surviving eclectic residences of Chinese immigrant pioneers and many of their descendents who, for the most part, flourished in their new homelands while living in dwellings reminiscent of those in China. This book presents the eclectic nature of their residences in terms of style, space, and materials. A companion volume will focus on the full range of objects enjoyed by Peranakan families within their architectural spaces or settings—the rooms—of their terrace houses, bungalows, and mansions as well as the layers of ornamentation around and about these residences. It is clear that these families were proud of their Chinese heritage.

The maintenance of that which is familiar while adapting to new circumstances is a recurring theme in Chinese history. The pushing out from core areas into frontier zones, indeed the sinicization of both landscapes and indigenous peoples, is a dominant part of China’s historical narrative. While complete families and whole villages in China sometimes migrated without ever going back to their home villages, there also was a tradition of sojourning in which fathers and/ or sons left with the expectation of only a temporary stay away before returning home. In Chinese history, merchants and financiers from the Huizhou and Shanxi areas, especially, epitomize the concept of sojourning. The resigned sentiments of this concept for a sojourning merchant and dutiful household head from Huizhou can be sensed in the note: “Those like us leave our villages and towns, leave our wives and blood relations, to travel thousands of miles. And for what? For no other purpose but to support our families” (Berliner, 2003: 5). Like those from Huizhou and Shanxi, traders, peasants, and coolies from the southeast coastal provinces of Fujian and Guangdong sojourned and settled in far-flung places, including Southeast Asia.

This engraving shows the various types of boats plying the waters along the north coast of Java. Clockwise: Javanese prahu; Chinese junk; coastal fishing boat; and Javanese junk.

Reified by scholars as “mobility strategies,” sojourning, whether in metropolitan regions of China itself or to a distant outpost in Southeast Asia, was for most traditional families a well thought out and logical traditional practice that heightened aspirations, providing enterprising families with opportunities for diversifying sources of income and acquiring wealth. Sojourning took many forms. In the fifty years from the late nineteenth century to the middle of the twentieth century, for example, some 25 million peasants from the densely populated North China plain provinces of Hebei and Shandong traveled seasonally to the relatively sparsely populated areas of Manchuria in order to open up for cultivation what were essentially virgin lands. They were called “swallows” or yan by their kinfolk because of the seasonal rhythm of their sojourn (Gottschang and Lary, 2000: 1). G. William Skinner, in his presentation of mobility strategies in late imperial China, provides a contemporaneous description of the Hu family’s approach to sojourning that involved not only trade in salt and porcelain but also finance and foreign trade (1976: 345):

When a family in our region has two or more sons, only one stays home to till the fields. The others are sent out to some relative or friend doing business in some distant city. Equipped with straw sandals, an umbrella and a bag with some food, the boy sets out on the journey to a place in Chekiang [Zhejiang] or Kiangsi [Jiangxi], where a kind relative or friend of the family will take him into his shop as an apprentice. He is about 14 years old at this time. He has to serve an apprenticeship of three years without pay, but with free board and lodging. Then he is given a vacation of three months to visit his family, who in the meantime have arranged his marriage for him. When he returns to his master he leaves his wife in his old home. Every three years he is allowed a three months’ vacation with pay which he spends at home.

This strategy to acquire wealth, which was pursued by territorially based lineage systems in inland China, operated as well in the coastal villages and towns of southern Fujian, and later in Guangdong. In this coastal region, embayed river ports and their hinterlands were the principal homelands for peasants, laborers, and traders who set sail in junks along the coasts and across the seas into what was for some terra incognita, but for many others parts of well-known trading networks.

Beyond the borders of imperial China, no area of the world experienced more sustained contact with Chinese or in-migration of Chinese over a longer period of time than the region referred to today as Southeast Asia, and which the Chinese have historically called the Nanyang or Southern Seas. Characterized by landmasses, peninsulas, and islands of many sizes, this is a region of great complexity and vast expanses, yet significant interdependence. Most of the maps of Southeast Asia show the region as a pendulous outlier of mainland Asia at a substantial distance from both China and India. Yet, from a Chinese perspective, the Nanyang was a sea-based region where even the most distant islands could be reached by sailing along well-known and charted routes. The maritime system within which Chinese coastal traders operated actually spanned an area greater than that of the Mediterranean Sea. Including both the East China Sea and the South China Sea, the immense maritime region stretched 5000 kilometers from Korea and Japan in the north to the Malay Archipelago in the south, and 1800 kilometers from coastal China eastward, beyond Taiwan, to the Philippines. Perhaps as many as 80 percent of the 35 million who trace Chinese ancestry and live beyond the political boundaries of China reside today in the crossroads of Southeast Asia.

Topside activity on a Chinese junk as depicted in a circa 1880 engraving.

Although this colorful view of a Fujianese junk is off the coast of Nagasaki, Japan, similar vessels plied the routes throughout the Nanyang.

Arab, Indian, Japanese, and Chinese merchants arrived in the regional trading ports of Southeast Asia more than a thousand years before the appearance of the Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch, French, and English. Raw and processed silk was carried from China along the Maritime Silk Road westward through the Indian Ocean where it was exchanged for exotic items from Europe. Among the earliest concrete evidence of the direct trade between China and the western Indian Ocean was a ninth-century Arab or Indian shipwreck filled with Chinese ceramics that was excavated in 1998–9 off Beitung Island between Sumatra and Borneo (Flecker, 2001: 335ff). Moreover, beginning in the eighth century, residential quarters called fanfang for foreign traders from Western Asia were located in Chinese port cities, including Guangzhou (Canton) in Guangdong and Quanzhou (Zaytun) in Fujian as well as farther north in Ningbo (Mingzhou) and Hangzhou in Zhejiang. Exotic commodities such as ivory tusks, gold, silver, pearls, sandalwood, kingfishers’ feathers, pepper, cinnabar, amber, and ambergris, among many other precious goods, found their way to China from the distant lands via the southern sea trade.

In time, the polities within the Southeast Asia region increasingly were brought within the Chinese tribute system that peaked during the Ming dynasty in the fifteenth century. Zheng He, the Muslim Chinese mariner who carried out seven fabled expeditions between 1405 and 1433, traversed the region, reaching some forty destinations that stretched from the Horn of Africa eastward along the southern, southeastern, and eastern shores of Asia. Over the following centuries, many of the ports visited by Zheng He became hubs for Chinese trading networks as well as sites for Chinese settlement and development. Even today, many of these places recall in their historical narratives the visits by Zheng He six centuries earlier.

The South China Sea as well as the East China Sea to its north had well-charted and well-traveled routes—a veritable maritime system of trade routes—that linked small and large ports across a vast region.

Sometimes sojourning resulted simply because Chinese traders were forced to stay for many months at a time at distant emporia waiting for the seasonal shifting of the monsoon winds. Indeed, over the centuries, the seasonal reversal of monsoonal winds was critical in establishing the trade patterns of Chinese traders. From September to April, the winds blew from the northeast to southwest carrying sailing ships from China southward. From May to September, the flow was reversed with the arrival of the southwest monsoon. Following these same routes, Arab traders took as long as two years for a round trip to China. From the fifth to the twelfth century, “the skippers trusted—when venturing out of the sight of land, to the regularity of the monsoons and steered solely by the sun, moon and stars, taking presumably soundings as frequently as possible. From other sources we learn that it was customary on ships which sailed out of sight of land to keep pigeons on board, by which they used to send messages to land” (Hirth and Rockhill, 1911: 28). By the twelfth century, maritime navigation improved with the introduction of a “wet compass” or yeti luojing, a magnetic piece of metal floating in a shallow bowl of water. Zhao Rukua, also known as Chau Ju-kua, a customs inspector in Quanzhou during the Song dynasty, chronicled in his book Zhufan Zhi (Records of the Various Barbarous Peoples) the places and commodities known to peripatetic Chinese during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. It was in this way that Chinese sojourners and settlers populated distant lands in increasing numbers as both sojourners and settlers. Their tales of prospects and opportunities no doubt infiltrated the outlooks and hopes of others in their home village.

The greatest flow of Chinese migrants by sea occurred from the mid-eighteenth century through the early twentieth century. While Wang Gungwu describes four overlapping out-migration patterns from southern China to Southeast Asia, only two will be discussed (1991: 4–12). Huashang, Chinese traders/merchants/artisans, comprised the dominant and longest lasting pattern. Huashang during the early periods generally settled down and married local women even when they had a wife in China. As their businesses became more profitable, other family members might leave China and join them. Some Huashang returned to China, according to the rhythm of trade, chose a spouse, and then maintained separate households for their different families. The Huashang type of migration pattern was employed especially by Hokkien migrants from southern Fujian to the Philippines, Java, and Japan; the Hakka on the island of Borneo; and those originating in the Chaozhou region of northeastern Guangdong province. It is both a fact and a curiosity that the Huashang pattern of migration had been practiced for many centuries within China.

Huagong were Chinese contract workers who arrived between the 1850s and the 1920s, usually as sojourners who intended to earn money and then return to their home villages to live out their remaining days. Unskilled contract workers were usually referred to as coolies, an English loanword whose roots reside in many Asian languages, including the Hindi word for laborer, qūlī, and the Chinese term kuli, meaning “bitter work.” Huagong especially played important roles in the opening up of rubber and palm plantations in Sumatra as well as tin mines and plantations along the Malay Peninsula. Substantial numbers of Chinese contract workers/coolies or Huagong also migrated to North America and Australia where they worked as laborers in mining enterprises and in railway construction. As opportunities arose, some of those who arrived as coolies or traders eventually became storekeepers or artisans, while others became farmers or fishermen. Patterns of settlement and return, living and working, varied from period to period. Indeed, as described by Anthony Reid, “It is the curious reversals of the flow southward, periodically running evenly, occasionally gushing, sometimes tightly shut, more often dripping like a leaking tap, that provide the rhythm behind the historical interaction of China and Southeast Asia” (2001: 15). While many other broad and complex topics—the history of migration, reputed business acumen and entrepreneurship, acculturation and assimilation, as well as tortuous issues relating to loyalty and nationality—are important and worthy of study, they will not be explored in this book.

Descendants of both Huashang and Huagong are found today throughout the countries of Southeast Asia where popular lore as well as the memories of descendant families trumpet tales of once penniless males who came to “settle down and bring up local families” (Wang Gungwu, 1991: 5). Through what is called chain or serial migration, pioneers arrived first, then sent information about new opportunities to those back home, which then spurred additional migration from their home villages. The ongoing arrival of related individuals helped maintain connections between the original homeland and new locations. Indeed, for many, their hearts remained back in China, and they saw themselves as Chinese in a foreign land. Yet, circumstances often meant that dreams of returning home were thwarted, and sojourners became settlers, forced to “bear hardship and endure hard work,” chiku nailao, as the common phrase ruefully states it, dashing their prospects of “a glorious homecoming in splendid robes,” yijin huanxiang, also yijin ronggui, as someone who had made off well and could have a proud homecoming. To do otherwise, according to Ta Chen, “his unrecognized distinctions might be compared with a gorgeous costume worn by its proud owner through the streets on a dark night” (1940: 109).

While this book highlights the homes of Chinese who had done reasonably well in the places they ventured to, it is important to keep in mind that most Chinese and their descendants lived and continue to live in much more modest homes in these places. Significant numbers of arrivals and their descendants, of course, never broke the debilitating chains of poverty, living on as an underprivileged underclass, the hardworking but powerless who dreamed of a better future that was never realized. Coolies, peasant laborers, rickshaw pullers, trishaw pedalers, pirates, fisherfolk, even prostitutes and slaves, lived in the back alleys, on the upper floors of commercial establishments, and on sampans along the banks of streams without ever “settling down” or dingju (cf Warren, 1981, 1986, 1993, 2008). Voiceless in life, they left illegible traces of their subsistence lives.

Old gravestones, such as these found along the sprawling slopes of Bukit Cina (Chinese Hill) in Malacca, Malaysia, which is the largest Chinese cemetery outside China, indicate the name of the ancestral village of the deceased.

Homelands in China

While it is common for outsiders to describe migrants from China in terms of the province of their origin, most migrants, in fact, traditionally identified home as a smaller subdivision, as a county or village. In southeastern China, river basins and coastal lowlands, circumscribed by surrounding hills, mountains, and the ocean, formed well-understood units of local culture and identity, shared cultural traits that were affirmed with the population speaking a common dialect. For Chinese, the awareness of origins in terms of a native place has traditionally been as significant as consciousness of the connections to forebears via their surname and lineage. Indeed, old gravestones and ancestral tablets memorialize place-based identity even when the deceased was many generations removed from the family’s homeland. Children and grandchildren born in an adopted homeland, moreover, inherit the native place of their immigrant parents and grandparents. Native-place associations, called tongxiang hui, and lineage or clan associations, tongxing hui, traditionally served as ready reminders of the two most meaningful relationships Chinese individuals had with their broader world. The place-name origins of migrants thus signify more than a link to an administrative division, more than a reference to a mere location. Rather, native places connote a shared cultural context that clearly separates one migrant group from another.

Until the end of the eighteenth century, a majority of the emigrants from China originated from Fujian, a province with a rugged coast-line and a tradition of building boats for fishing and seafaring. The encyclopedic Shan Hai jing (Classic of Mountains and Seas), an eclectic two-millennia-old compendium of the known world, states: “Fujian exists in the sea with mountains to the north and west”, Min zai haizhong, qi xibei you shan. With limited arable land to support a growing population, the Fujianese turned to the neighboring sea, using small boats for fishing and seagoing junks for distant trade to the Nanyang where they exchanged manufactured wares for food staples. “The fields are few but the sea is vast; so men have made fields from the sea” is how an 1839 gazetteer from Fujian’s port city of Xiamen viewed the maritime opportunities afforded its struggling population during the last century of the Qing dynasty (Cushman, 1993: iii).

Referred to collectively as Hokkien, the local pronunciation of the place-name Fujian, the homelands of migrants can be readily subdivided in terms of at least three main dialects found in areas to the south of the Min River in this complex and fragmented province. Called Minnan or “south of the Min River” dialects, each is a variant of the others and is centered on one of the area’s three major ports: Quanzhou, Xiamen, and Zhangzhou. Although the three dialects are mutually intelligible to some degree, and are spoken in geographic locations that are relatively near to one another, the speakers of these dialects traditionally have seen themselves as belonging to distinct local cultures with dissimilar mores. In neighboring Guangdong province, another source region for significant numbers of migrants to the Nanyang, are other dialect-based communities: Chaozhou (Teochew, also Teochiu) and Hainan hua (Hainanese), which are also in the family of Minnan dialects, as well as Kejia (Hakka) and, farther west, those who speak Guangdong hua (Cantonese). One characteristic shared by all of these groups is that they occupy areas either adjacent to or connected by short rivers reaching the Taiwan Strait that connects the East China Sea and the South China Sea.

These simple plans reveal the characteristic forms of residences found throughout Fujian. The white areas indicate the variety of tianjing, skywells that open up the buildings to air, light, and water.

Elongated two-storey urban residences in Guangdong include multiple skywells, narrow corridors, steep stairs, and stacked rooms.

Along the Fujian–Guangdong coast, there are countless areas that are known in the vernacular as qiaoxiang, literally “home township of persons living abroad.” The term qiaoxiang was used in the nineteenth century to apply not only to sojourners, temporary residents who were abroad, but also to those who had been away for generations. Those Chinese who left China were referred to as Huaqiao, a capacious term often translated as “overseas Chinese,” but essentially meaning “Chinese living abroad.” “Overseas Chinese” itself historically has been a descriptor of considerable elasticity, applying not only to those temporarily abroad but also to those who are Chinese by ethnicity but have no actual connection with China. Guiqiao, indicating those Chinese who returned from abroad, and qiaojuan, indicating the dependants of Chinese who are abroad, are expressions still heard today. Qiaoxiang, as “emigrant communities,” traditionally were bound by social, economic, and psychological bonds in which emigration became a fundamental and ongoing aspect of country life. While poverty and strife may have induced earlier out-migration, over time migration chains create a tradition of going abroad that propels outward movement. In some ways, overseas sites arose as outposts of the qiaoxiang itself, linked to it by back and forth movements of people and remittances of funds to sustain those left behind. Indeed, as Lynn Pan reminds us, “emigrant communities are not moribund. The men might be gone but, collectively and cumulatively, they send plenty of money back. Many home societies have a look of prosperity about them, with opulent modern houses paid for with remittances by emigrants who have made good abroad” (2006: 30).

As later chapters will reveal, individual qiaoxiang are linked with specific locations in Southeast Asia, indeed throughout the world. Emigrants from the Siyi or Four Districts of Guangdong province on the west side of the Pearl River, for example, favored migrating to the goldfields and railroad construction opportunities in California. Farther east and clustered around the port of Shantou, once known in English as Swatow, those who spoke the Chaozhou dialect sailed to Siam and elsewhere in Southeast Asia. Kejia or Hakka from the uplands beyond Shantou, and accessible to it via the Han River, spread themselves widely. The area between Xiamen and Quanzhou, more than other areas in Fujian, fed the migrant streams throughout Southeast Asia. Jinjiang, once a county-level administrative area just to the south of the port of Quanzhou, not only looms large as the homeland of countless migrants throughout Asia, it is the ancestral home of over 90 percent of those of Chinese descent in the Philippines. Each of these distinct qiaoxiang areas is noted for its own variant forms of vernacular architecture, which explains in at least a limited sense many of the differences in the residences built by migrants in their adopted places of residence. The section below highlights some of the common features among these vernacular traditions, while later chapters will reveal some of the differences.

Old Homes Along China’s Coast

Chinese dwellings throughout the country share a range of common elements even as it is clear that there are striking regional, even sub-regional, architectural styles. Given China’s vast extent, approximately the size of the United States and twice that of Europe, it should not be surprising that there are variations to basic patterns that have arisen as practical responses to climatic, cultural, and other factors. While there is no single building form that can be called “a Chinese house,” there are shared elements in both the spatial composition and building structure of both small and grand homes throughout the country. In addition, Chinese builders have a long history of environmental awareness in selecting sites to maximize or evade sunlight, capture prevailing winds, avoid cold winds, facilitate drainage, and collect rainwater. Details of these similarities and differences are considered at length in some of my other books (Knapp, 2000; 2005).

Adjacent open and enclosed spaces are axiomatic features in Chinese architecture, whether the structure is a palace, temple, or residence. Usually referred to in English as “courtyards” and in Chinese as yuanzi, open spaces vary in form and dimension throughout China and have a history that goes back at least 3,000 years. Courtyards emerged first in northern China and then diffused in variant forms as Chinese migrants moved from region to region over the centuries. The complementarity of voids, apparent emptiness, and enclosed solids is metaphorically expressed in the Dao De Jing, the fourth-century bce work attributed to Laozi: “We put thirty spokes together and call it a wheel: But it is on the space where there is nothing that the usefulness of the wheel depends. We turn clay to make a vessel; But it is on the space where there is nothing that the usefulness of the vessel depends. We pierce doors and windows to make a house; And it is on these spaces where there is nothing that the usefulness of the house depends. Therefore just as we take advantage of what is, we should recognize the usefulness of what is not” (Waley, 1958: 155).

While sometimes what is considered a courtyard is simply an outdoor space, a yard, at the front of a dwelling, a fully formed courtyard must be embraced by at least two buildings. Two, three, or four structures along the side of a courtyard create an L-shaped, inverted U-shaped, or quadrangular-shaped building type. Nelson Wu called such a composition a “house–yard” complex, with the encircling walls creating an “implicit paradox of a rigid boundary versus an open sky” (1963: 32). The framing of exterior space by inward-facing structures arranged at right angles to and parallel with the fronts of other buildings creates configurations that are strikingly similar to the character 井, a well or open vertical passage sunk into the confining earth. The proportion of open space to enclosed space is generally greater in northern China than in southern China, fostered by the desire to welcome sunlight in the north but to avoid its intensity in the south. As a result, courtyards found in southern homes are usually much smaller than elsewhere in the country.

Chinese in southern China use the term tianjing to describe open spaces within their dwellings, whether they are fairly large or indeed even mere shafts that punctuate the building. The term tianjing is usually translated into English as “skywell” or “airwell,” terms that are especially appropriate in multistoried structures where the verticality of the cavity exceeds the horizontal dimension. Atrium-like tianjing are found in Ming and Qing dynasty residences throughout central and southern China, including along the coastal areas. Tianjing evacuate interior heat, catch passing breezes, shade adjacent spaces as the sun moves, and lead rainwater into the dwelling where it can be collected. Adjacent to skywells, which are relatively bright compared to enclosed darker rooms, “gray” transitional spaces such as shaded verandas are common in Fujian and Guangdong. In order to reduce humidity levels that effectively lower the apparent temperature felt by the body, architectural devices such as open-faced lattice door panels, half-doors, and high-wall ventilation ports are employed in southern houses to enhance ventilation. Throughout Southeast Asia, where the sun is elevated in the sky year round and ambient temperatures are high, it is not surprising that immigrants from southern China continued to use tianjing in their new homes. Many examples will be shown in the chapters that follow.

Throughout southern Fujian and eastern Zhejiang, manors with front-to-back halls and perpendicular wing halls represent the typical fully developed residential form. This residence of the Zhuang family is located in the Jinjiang area of Fujian province.

Where building lots were restrictive and space was at a premium, Chinese builders traditionally adjusted the dimensions and shapes of their structures. In urban areas, narrow residences adjacent to each other along a street were constructed as long structures with small skywells punctuating the corridor-like receding building. Where it was possible to construct a more extensive residence, either narrow or broad parallel structures were constructed alongside a wider central unit. Over time, if wealth and family circumstances allowed, additional side-to-side wing units were added. Examples of this modularity and replication of enclosed and open spaces can still be seen throughout Fujian and Guangdong, indeed throughout China.

The Tan Tek Kee Residence, Jinjiang

Migrants who departed Fujian and Guangdong were generally poor, leaving behind family homes that were simple and unremarkable. In some cases, however, where the family already had a home and migration by a son was part of a family’s strategy to further increase its wealth, there was usually hope that improvements in the residence would take place as remittances came from abroad. In the early twentieth century, travelers in the region noted the presence of emigrant communities because of the superior quality of the dwellings. Ta Chen states that these fine homes, traditional and modern, were “the most effective way to express one’s vanity.” Moreover, “an effective display of pride does not mean only a large house, but it has to have evidences of taste and culture. This may be supplied either by modernity or, on the contrary, by an ostensible show of liking for those things which traditionally stand for refinement.... The ideal of ‘complete happiness’... is not in fact anything new the emigrants bring back with them from abroad, but embodied in the folkways of the countryside. What they do contribute is financial ability to gratify these tastes and, sometimes, innovations which produce curious contrasts between old and new in the homes and the furnishing of homes” (1940: 110–11).

While there is no “typical” home of a migrant, the residence discussed below illustrates the dynamic nature of space in a fully formed residence of a family who sent their son to the Philippines. The dwelling expresses what Chinese broadly considered a fine home for harmonious family life during the late imperial period. It exhibits well the layout and materials of a traditional Fujian dwelling, as well as reflecting aspects of family organization, ways of living, and ritual requirements in one of China’s preeminent qiaoxiang in Jinjiang county to the south of Quanzhou. Because of deterioration over the past half-century and lack of documentation, however, it is not possible to ascertain with certainty the specific changes brought about by the remittances from their successful son.

This expansive residence was built sometime during the latter half of the nineteenth century either by the father or grandfather of Tan Tek Kee, who was born in the family home in 1900. Family lore recalls that Tan Tek Kee’s forebears themselves had migrated southward from Henan province in northern China, perhaps an explanation for the fact that descendants have been tall compared to their neighbors. Tan Tek Kee’s father is said to have gained fame and perhaps some modest wealth from his fishball business. Fishballs, made from minced fish mixed with other ingredients, are still a distinctive component of cuisine in Fujian, whether served in noodle soups or deep-fried, skewered, and served with various sauces. Raised by his elder brother and sister-inlaw, Tan Tek Kee married at the age of thirteen or fourteen before being sent to the Philippines in 1914 or 1915 with family friends surnamed Cheng, who served as his surrogate parents. Working first as a cook, then a courier, and then later a manager, he branched out on his own in the 1930s, even as he made many return trips to his family’s Jinjiang home and his birthplace. According to family custom, he retained some rights to the residence, which was sufficiently roomy so that the multigenerational families of his surviving siblings lived comfortably. The father of ten children, two of whom were adopted, Tan Tek Kee over time amassed sufficient resources to bring his wife to Manila where he died and was buried in 1966.

Resembling the typical architectural pattern seen on the previous page, the residence of Tan Tek Kee, also in Jinjiang, is much as it was during the late nineteenth century.

At one time, the home was a solitary structure surrounded by rice paddies, but as can be seen in the bird’s-eye view photograph, new-style multistoried structures have encroached upon it, diminishing to some degree not only its tranquility but also heightening its sense of being forlorn. Like other residences of this type, it was built with an overall rectangular shape, which could be considered square if one includes the walled open space in front. While its overall form remains today intact, renovation and dilapidation have altered its original appearance. In terms of the composition of its spatial elements, the three-bay central structure, with a generous square tianjing between the entry hall and the ancestral hall, has a pair of perpendicular structures that complete the quadrangular core. A second pair of parallel, perpendicular two-storied buildings was added to complete the layout. Each of the outer wings, called hucuo, is separated from the core building by a narrow longitudinal tianjing running from front to back, which could be entered directly from the outside via a doorway. Indeed, it would have been these two side entries that would have been used on a daily basis in the past, rather than the recessed central entryway, with its elegant didactic ornamentation.

From just inside a magnifi-cent entryway, which abounds in carved stone and brickwork, this view is across the first skywell looking towards the first hall.

Cut granite slabs, some of which are carved, were used throughout the residence for the foundation, steps, sills, and columns. Granite or huagangshi, a coarse-grained igneous rock known for being more durable than marble, was used in the core building. Readily available in the nearby mountains of the province, yet considered an expensive building material, granite has traditionally been employed as a building material in temples and fine residences throughout central and southern Fujian. (Today, parenthetically speaking, Fujian is a major source for polished granite countertops used in modern kitchens and bathrooms throughout the world.) The sunken entryway was created using interlocking vertical and horizontal pieces of granite of different dimensions. At the base of the entry portico, as well as inside the core structure, granite was used as flooring. After crossing the raised granite threshold, a visitor will note that the middle bay, including the full tianjing, is covered completely with granite dimension stone. Along the sides, granite slabs were used only to frame areas that were covered with kiln-fired red tile flooring. As the view from the entry hall through the tianjing to the main hall reveals, the tianjing was sunken, with drains to lead rainwater out of the home. Just beyond the tianjing and in front of the main hall, the level of the flooring was elevated to express the hierarchical importance of the hall.

Set upon carved granite bases, square granite columns with auspicious couplets carved into them, were placed around the tianjing. Atop each of these stone columns was fitted a short wooden column, linked together by mortise-and-tenon joinery, to lift the wooden framework supporting the roof. The horizontal and vertical wooden members as well as the elaborate wooden bracket sets still comprise an important ornamental aspect of the house that complements the hard stone beneath the feet. No room was designed to have more richness than the main hall, which was surrounded with solid wooden walls and sturdy hardwood columns. Sadly and tragically in recent years, the ridge beam that supported the roof rotted and fell to the floor, bringing down with it the wooden purlins, rafters, and roof tiles, and leaving the room open to the elements. What once must have been an imposing family altar with ancestral tablets atop it, has been replaced by a low table with a small collection of old photographs and votive pieces with a triple mirror above.

Throughout this region of Fujian, the exterior walls of many dwellings are constructed of either slabs of cut granite or composed only of red bricks, hongzhuan, made of local lateritic soils and fired in nearby kilns. The ancestral home of Tan Tek Ke, on the other hand, was constructed using both granite and red brick as structural and ornamental building materials. From a distance, the red brick of the façade and sidewalls appears to be laid with common bonds, yet on closer inspection it is clear that all of the red brick in the façade was used to serve ornamental purposes, with a number of different motifs. Adjacent to the entryway, the thin red bricks were decorated with a zigzag pattern of dark lines, which appear to have been painted on the bricks before they were fired. Surrounding each of the four granite windows are thin red bricks in a modified herringbone pattern with a box bond. Unlike Western bricklaying patterns, where stretchers vary to create named bonds, this Chinese pattern utilizes the wider top or face of the brick and the narrow header, which is darkened, to create the pattern. Carved bricks and tiles in geometric and floral patterns were also arrayed as a frame around the block of herringbone patterned bricks. Carved human figures were inset in five locations on each of two walls, but most are still obscured by a coating of white plaster. During the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, these carvings were plastered over as a precaution in order to prevent their destruction, but only several have been restored.

Granite, a widely available building material in the Quanzhou area, is used not only for flooring but also for columns and the bases of columns and is carved into ornamental panels.

Seven slender granite slabs are employed here to create one of the windows along the front wall, which is covered with thin red bricks.

Although the residence is generally in good condition, one area of serious damage resulted from the collapse of the main beam supporting the roof above the ancestral hall, which then opened the area to chronic water damage.

Along each side of the skywell, the eaves are supported by an assemblage of timbers, some of which are elaborately carved.

The gaze of a visitor approaching a residence of this type is drawn to the upswept ridgeline above the entry hall at the center of the complex, which is matched by a more impressive, and slightly higher, one on the main hall behind. This type of graceful ridgeline is called the yanwei or “swallowtail” style partly because it is upswept and tapered, but mainly because it is deeply forked at its tip. Each of the adjacent perpendicular buildings was constructed with a lower upswept ridgeline, with shed roofs that framed the sides of the central tianjing. These created a pair of flat rooftop terraces, which were accessible from below using stairs, outdoor spaces that once provided a place for quietude to enjoy the breeze in the evening or the moon at night. The relatively gentle pitch of the roofs was governed by the spacing ratio between the beams and struts that supported the roof purlins. Arcuate roof tiles, which appear like sections of bamboo, were used to cover the roofs. Today, the roof of one of the outer wing structures is undergoing renovation and currently only has a tar paper surface, which is held in place by bricks. What once was its symmetrical double on the other end of the house has been altered significantly with the removal of the original second floor and its replacement by a “modern” higher structure with a flat roof.

Traditional residences such as this have significantly declined in number over the past half-century, not only because of the disinterest of descendants and lack of maintenance but also because of deterioration due to age, dilapidation, and abuse. After 1949, especially during the class struggles associated with Land Reform, both land and housing were confiscated from landlords and merchants before they were redistributed to poor peasants. As a result, many grand residences, which represented the patrimony of Chinese living abroad, came to be occupied by destitute local families whose interest was more in shelter than preservation. While the 1950 Land Reform Law stated that ancestral shrines, temples, and landlords’ residences “should not be damaged,” and together with the “surplus houses of landlords... not suitable for the use of peasants” be transformed into facilities for “public use” by local governments, most began a process of corrosive decline that was accelerated during the transition to communes, which began in 1958. During this period, in which there was a craze for collectivized living, stately structures representative of China’s glorious architectural traditions—residences, ancestral halls, and temples—were transformed into dining halls, workshops, administrative headquarters, and dormitories, among other group-centered uses for the masses (Knapp and Shen, 1992: 47–55). Moreover, during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution a decade later, there was frenzied activity throughout the country that brought about the smashing and burning of ancestral altars and tablets, including substantial amounts of applied ornamentation handed down from the past. Ornamental and ritual elements made of wood, clay, and porcelain suffered the greatest loss, while those made of stone and brick managed to survive in significant numbers.

During what is known as the Reform and Opening-up Period in the decade after 1979, Overseas Chinese as well as local families, whose property in China had been confiscated during “the high tide of socialism” after 1949, were invited to apply for its return. Descendants from all over the world, including Southeast Asia, some of them generations removed from those who built the old homes, traveled to China in search of their family legacy. Families thus were able to assess what had been lost and what remained, while contemplating what to do with the property they once thought had been lost. Many stately old residences were quickly cleared of non-family members who occupied them, were cleaned of grime, and were repaired. In some cases, where furnishings had been removed and stored, they were returned, but in most cases furniture was not recoverable. Some families were able to reclaim their material links to their past, passing the structures on to family members still living in China. In other instances, overseas families provided funds for the restoration of a grand home with the title transferred to a governmental body or organization that promised to open the home as an historic site. The Chen Cihong manor shown on pages 262–7 is an example of this type of effort.

When the ancestral home of Tan Tek Kee was fully returned to the family, it had been stripped of all of its furniture and had suffered badly from lack of maintenance. The ritual heart of the residence in the main hall was derelict, with all of the tangible material elements long gone, and only faded memories remain. What once had been exquisite compositions of fine furnishings, ritual paraphernalia, paintings, and other art works, all had been lost. In recent years, the collapse of the central ridgepole above the altar opened the heart of the dwelling to water damage, which has accelerated its deterioration since resources have not been expended to make necessary repairs. The residence today is owned by descendants of Tan Tek Kee, who now must struggle with decisions about its preservation. While most of them today live comfortably beyond Fujian in the Philippines and Hong Kong, they have put forth substantial funds in an effort to both maintain and restore the patrimony of their forebear. Making decisions within an extended family about allocating resources and how the burden should be shared is not easy. Without the daily life and periodic ritual of the family that once occupied this fine home, and who gave it life, the structure today is a melancholy shell of its former splendor. Today, only a caretaker and his family now occupy the rambling old dwelling in order to keep it clean and protect it from vandalism while distant family members ponder its future.

New Homelands in Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, like other major realms of the world, as discussed above, is diverse and fragmented in terms of its physical and cultural geographies. The region can be divided fundamentally into two contrasting subdivisions: an Asian mainland that extends south from China, and an array of large and small islands that includes the world’s most extensive archipelago. Volcanic peaks, mountain spines, rugged coastlines, long rivers, short rivers, deltas, mangrove swamps, rich soils, and virgin forests are but some of the line-up of physical features that indigenous people and immigrants have adapted to.

It is likely that the Tan Cheng Lock residence on the right and the narrower residence on the left, which share an architectural style, were built at the same time in Malacca, Malaysia. Perhaps they were originally owned by a single family who later sold the units to different families.

Much of what we know of Chinese migration in Southeast Asia is fragmentary, with ebbs and flows guided both by imperial policy and individual decisions made by resourceful seaborne traders. During the Song dynasty in the twelfth century, the Ming dynasty in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, and throughout the Qing dynasty, which began in 1644, Chinese trading communities of various sizes and compositions emerged at scattered port locations throughout the islands and peninsulas in the Nanyang. Over time, what once were scattered and isolated became tied into commercial networks. The arrival of Europeans, first as traders and then as colonialists, as well as Japanese, brought about competition and rivalries even as Chinese traders flourished and arriving Chinese settlers increased in number. Enterprising Chinese immigrants, as later chapters of this book will reveal, commercially exploited the profuse variety of flora and fauna as well as minerals and metals, resources providing work and a modest livelihood for countless contract laborers and bountiful wealth to a smaller number of migrants from China. The plantation cultivation of rubber, coffee, sugar, and spices, in addition to the collection of birds’ nests from caves in the wild and exotic flora and fauna from the biodiversity-rich ecosystems, played key roles in these transformations. The sections that follow will examine the dispersal of Chinese migrants, emphasizing the disparate character of history and geography of various settlement sites, as a prelude to the featured residences in Part Two.

Malacca

In the area clutched between the Malacca River and the Strait of Malacca, a casual visitor sees old buildings lining the narrow streets that appear on the exterior to be quintessentially Chinese. Indeed, Chinese characters arrayed above the lintels and windows and on the door and shutter panels, as well as the bulbous red lanterns hanging beneath the eaves, all seem to proclaim that this neighborhood has deep roots as a place of settlement by Chinese immigrants and their descendants, perhaps even to the earliest days of Malacca. Looking more closely at the exteriors, however, one also observes Dutch-period architectural features, Victorian glazed tiles, eclectic façades of uncertain age and origin, Chinese protective amulets, rooflines that span East and West, among other elements that confound the observer’s judgment. Glimpses through the doorways of hotels, restaurants, shops, even residences, seem to affirm that the occupants are principally Chinese in origin.

Those fortunate to be invited into homes along the lanes see that many are quite similar to the shophouses and terrace homes found in towns in southern China in that they have prominent skywells—small courtyards—that open up the interiors to light and air. In many of these residences, moreover, there is an abundance of antique Chinese and Western furniture, a proliferation of symbolic Chinese ornamentation, a mélange of curios, art works, and bric-a-brac from China as well as Europe, and an occasional architectural detail that appears odd in a Chinese home. It is a fair to ask: what can old residences like these tell us of the lives, aspirations, and tastes of the Chinese, and others, who have occupied them?

These buildings and these streets in Malacca indeed are more than they seem at first glance. On closer examination, one is able to see a multifaceted and layered history of successive occupancy by different groups, with the Chinese being but one prominent part, over five centuries from the 1500s to the present. Historical geographers call the succeeding stages of human inhabitation of a location over intervals of historic time “sequent occupance.” The coming and going of a group, which entails using and abandoning areas and buildings, is a dynamic process of creating and modifying to meet different cultural norms. Indeed, any of the residences that appear to be Chinese are, in fact, transformed artifacts representing both added and deleted elements when compared to what was inherited from others. To help understand similarities and differences, Malacca needs to be looked at in terms of different temporal and spatial scales.

At one scale, there is a sequence represented by the successive arrival in Malacca of different nationalities, some more powerful than others, but each leaving significant imprints on the landscape. Once a small and remote fishing village inhabited by indigenous Malays, Malacca began to develop as a port in the fourteenth century under the leadership of Parameswara, a Srivijayan prince from Sumatra. The Portuguese arrived in 1511, surrendering control to the Dutch in 1641 for a century and a half of development, before passing the region to the British in 1795, with a Dutch interlude again from 1818 to 1824, at the end of which the Dutch returned Malacca to the British in exchange for territory in Sumatra. Each of these occupancies was overlain by the arrival, presence, and activity of Muslim Arabs, Hindus from the Gujarat and Tamil regions of today’s India, and, of course, Chinese from Fujian and Guangdong provinces. All of these interacted with indigenous Malays. Moreover, the rise of Penang in 1786 and Singapore from 1819 onwards was accompanied by Malacca’s slipping in importance as a trading center with its relegation to a relative backwater. One result of this new status was that the layout of the town and its solid buildings, which passed from one group to another, were for the most part not destroyed but survived to be occupied and were then transformed by different residents.

As will be seen with later examples, the entryway of many Chinese homes differs little from temples in terms of form and ornamentation, such as Malacca’s Cheng Hoon Teng Temple, whose origins go back to the 1640s and is Malaysia’s oldest Chinese temple.

The expansive three-bay structure of the Cheng Hoon Teng Temple is made possible because of an elaborate wooden structural framework. This is a view towards the main and side altars.

Built early in the twentieth century on the northern outskirts of Malacca, in Tranquerah, this narrow terrace residence houses a multigenerational family. The façade is richly decorated with stucco patterns and calligraphic ornamentation. Just inside the entryway is a round table with a formal grouping of furniture with mother-of-pearl inlay. Beyond this area is a sky-well framed with fluted columns, which are painted to match the façade.

After having been used as a storehouse for antiques for thirty years, this two-storey terrace house along Heeren Street in Malacca was purchased in 2003 by a couple who have restored it and opened it as a bed-and-breakfast inn.

Between the early nineteenth and the twentieth century, Singapore shop-houses were transformed in height and width as well as style.

When the Portuguese arrived, they constructed a pentagonal fort on the south side of the Malacca River, while some joined Gujaratis and Tamils on the north bank where they lived in simple dwellings built from easily available materials such as timbers, mud, and thatched nipa palm called attap. Towards the end of the sixteenth century, successful merchants began to build more substantial houses in an area that was favored by cool breezes from the sea and came to be called Kampung Belanda or “Dutch Village.”

After disastrous fires that accompanied the Dutch siege in 1641, in addition to constructing residences and other buildings in Malacca’s administrative and commercial center, the Dutch laid out along the north side of the river a somewhat rectangular street plan with two major roads running parallel to the coast, which were intersected by minor ones. In this area, increasingly wealthy Dutch and other settlers constructed brick and stone homes with their backs aligned along the sea and their fronts along a road called Heerenstraat or “Gentlemen’s Street,” which was later renamed Heeren Street by the British. In time, multistoried residences, which were narrow in the front and elongated as they receded towards the water, were built, then no doubt modified from time to time to meet changing needs. Similar, but generally less grand homes were built along Jonkerstraat, an inland road parallel to Heerenstrat. While some of the elements of these evolving houses drew upon experiences the Dutch had in colonies elsewhere in the tropics, the residences also reflected the designs known to Chinese masons and carpenters who did much of the actual construction using common building practices in use in China. The intersecting of Dutch and Chinese patterns in the organization of space, building structure, fenestration and roofing of many residences along these narrow old roads is indisputable yet still, to some degree, remains a puzzle.

The successive arrival of Portuguese, Dutch, and British colonialists and the roles played by Indian and Chinese mercantile immigrants brought about Malacca’s transformation into one of the region’s most important entrepôt by virtue of its strategic location on the Strait of Malacca. The multicultural heritage of Malacca has bequeathed not only a remarkable vitality to an arguably significant historic city but also a mixed assemblage of heritage buildings. The destruction of old buildings, unbridled land reclamation, construction of high-rise buildings, and inattention to traffic management, all in pursuit of short-term commercial gains, have contributed to diminishing Malacca’s frayed multicultural past. While the preservation of Malacca’s exceptional material heritage remains imperiled, significant elements of the city’s Chinese heritage remain.

The recently restored Cheng Hoon Teng Temple, whose origins go back to the 1640s, and Bukit Cina (Chinese Hill), an expansive cemetery that dates to the mid-fifteenth century, both exemplify the rich links between China and the Malay Peninsula. Marriage and concubinage involving males from China and local women gradually brought about a distinct community known as Peranakan Chinese, whose porcelain, cuisine, clothing, architecture, language, and literature are prominent aspects of their culture. Peranakan Chinese residences in Malacca as well as in Singapore and Penang, the original three Straits Settlements, include not only eclectic terrace homes, which are also called town-houses, but also ornate villas and mansions.

Four Malacca residences are featured in Part Two, which together provide insights into the historical, geographical, architectural, and social aspects of life in Malacca from the eighteenth into the early parts of the twentieth century. The restored shophouse at No. 8 Heeren Street (pages 42–5), which once served as a kuli keng, literally “the quarters where coolies live,” provides a simple spatial template for the succession of larger homes built later. No Peranakan Chinese Malaysian is better known than Tan Cheng Lock, whose ancestral home, also on Heeren Street (pages 46–57), reveals Dutch features plus multiple layers of Chinese and Western influences. Two buildings associated with the Chee family are discussed: one was built in 1906 to memorialize Chee Yam Chuan, the notable forebear of the lineage (pages 58–63), and another the late nineteenth-century residence of Chee Jin Siew (pages 64–9) that provides a glimpse of a substantial home that has undergone only limited restoration. While each of the townhouses, shophouses, and villas in Malacca is unique, they share common aspects that can be gleaned from looking at their façades, floor plans, and ornamentation.

Singapore

Cities like London, Rome, Paris, and Beijing, and even younger cities such as New York and Singapore, are veritable museums of changing architectural styles in which old residences and other structures encapsulate in their physical forms the dynamic nature of individuals, families, and communities. Scattered homes and buildings together tell the story of each city’s evolution and, to some degree, national history in microcosm, from humble beginnings to their flourishing as commercial or governmental centers. Old residences, in particular, help tell the story of once prominent families, even the whole era in which they lived, giving contemporary visitors an opportunity to experience, within the confines of four walls, how life was lived in times past. Through the massing of architectural form and structure as well as building style, including external features and interior spaces, the tempo and character of daily life of times past can be made understandable for the curious visitor. Furnishings and ornamentation point toward what a family valued, providing windows into understanding what their hopes and aspirations for themselves and sometimes even their descendants. This is as true of the homes of the wealthy as it is for those struggling to find a place of modest comfort for their families.

Established by the British East India Company in 1819 on the site of a fishing village on an island at the tip of the Malay Peninsula, the trading post that became Singapore emerged in the nineteenth century as a strategic hub of British commercial and military power in Asia. Sir Stamford Raffles, acknowledged as the founder of Singapore, outlined early on a town plan some three kilometers wide along the sea and two kilometers inland, with priority on creating efficient docking and unloading facilities along the Singapore River. In order to forestall the emergence of disorderly settlements, a plan was proposed that created a segregated layout defined by ethnic subdivisions: a European Town, a Chinese Campong, Chulia Campong for ethnic Indians, Campong Glam for Malays, and an Arab Campong. “Campong” is the Anglicized form for the Malay word “kampong,” which means a hamlet or village. As an entrepôt that welcomed traders, planters, and coolies, Singapore subsequently thrived with the arrival of immigrants from China, India, Malaya, and elsewhere, in addition to a significant number of enterprising Peranakan Chinese from Malacca and Penang.

This view across the rooftops of Singapore’s Telok Ayer area, the heart of Chinatown, in 1870 reveals the nature of urban shophouses at the time.

In the early years, in addition to Chinese merchants and artisans, Chinese peasants arrived in increasing numbers to open areas to the north and west of the port city for the production of gambier and pepper, which, as we will see, contributed to the wealth of Chinese businessmen resident in Singapore. An 1879 survey of the manners and customs of Chinese in the Straits Settlements tallied some 200 different occupations pursued by immigrant Chinese. While the intent of many Chinese newcomers was to return to China, many settled in the new homelands. “Many did not go back to China,” according to Victor Purcell, “because... they were too poor, but some did not return because they were too rich and dared to leave their property and their interests” (1965: 254).

Many of the early dwellings inhabited by Fujian and Guangdong immigrants in the Chinese Campong were flimsy Malay-type structures raised on stilts above the marshy ground. In time, this area expanded over four phases from the 1820s into the 1920s into what today is known as Chinatown, a robust commercial and residential district of eclectic shophouses of various designs. Paradoxically, Singapore’s “Chinatown” is but a single neighborhood in a country that is predominantly populated by the descendants of immigrants from China.

The elongated Singapore shophouse, which has been called an Anglo-Chinese vernacular form by Lee Ho Yin, provided working and living space for merchants, artisans, and service-oriented firms (2003: 115). Over the years, shophouses evolved in terms of relative scale while maintaining features such as the linear covered veranda known as the “five-foot way” and the presence of at least one interior skywell. Built contiguously in blocks separated by party walls, there is a lively rhythm to the columns, pilasters, shutters, and ornamentation of the façades of adjacent Singapore shophouses, with elements that are Chinese, European, and Malay.

Early in the twentieth century, some Chinese in Singapore constructed raised bungalows along the sea coast that resemble Malay rumah panggung.

The spacious raised veranda on the home shown above is a comfortable place throughout the day.

Constructed in 1896 by Goh Sin Koh, a timber and shipping merchant, and demolished in the the 1980s, this residence was the last expansive manor in Singapore in the architectural style of southern Fujian.

The eclectic style of the multifunctional Singapore shophouses in Telok Ayer, the heart of Chinatown, was in time carried over to their cousin, the purely residential structures called terrace houses or townhouses. By the later decades of the nineteenth century, as increasing numbers of new migrants arrived from China, Chinatown became overcrowded and unhealthy. Some Chinese merchants began to consider moving beyond their place of livelihood to more residential neighborhoods that were being developed, first in areas adjacent to Chinatown and before long elsewhere across the island. Nearby areas along Neil Road, Blair Road, Spottiswoode Park, and River Valley Road, then in the Emerald Hill area, once a nutmeg plantation, and later in the Joo Chait and Katong areas in the eastern part of Singapore, all became new centers of Chinese residential life. In these areas, a mélange of building types, predominantly shophouses and terrace houses, took root in varieties that defy easy summary (pages 80–9). As other Chinese families moved to the eastern section of the island early in the twentieth century, some built raised bungalows that evoke the Malay-style rumah panggung along the seacoast. Constructed on piles with a broad veranda and abundant fenestration, the design of these bungalows allowed air to move under and through them, thus increasing comfort for those living within. In addition, the possible flooding during high tides was mitigated by elevating the residence.

Several terrace houses are presented in detail in Part Two. Among the most interesting is the multistoried Wee family residence on Neil Road (pages 90–101), which was initially built as a two-storey structure between 1896 and 1897 that was subsequently raised to three storeys. More than a century old, this residence provides not only entry into the lives of an old Singapore family but also provides a template for understanding the layout and use of a typical terrace house. In 2008, after a successful restoration, the residence was opened as the Baba House Museum. Other terrace residences in the Emerald Hill, Blair Flat, and River Valley Road areas are also featured in Part Two.

During the nineteenth century, a coterie of tycoons, merchants with extraordinary wealth and power, emerged in Singapore. One of the most celebrated was Hoo Ah Kay, usually referred to as Whampoa (Huangpu) after his place of origin in Guangdong and the name of his father’s firm, Whampoa & Co. Whampoa was described as the “most liked Chinaman in the Straits,” “a fine specimen of his countrymen; his generosity and honesty had long made him a favorite,” and “a very upright, kind-hearted, modest, and simple man, a friend to everyone,” who was known for his “sumptuous entertainments” (Buckley, 1902: 658–9). He acquired a neglected garden on Serangoon Road about four kilometers outside town, where he built a “bungalow,” a magnificent country house, as well as an aviary and “a Chinese garden laid out by horticulturalists from Canton,” which became a “place of resort for Chinese, young and old, at the Chinese New Year” where “the democratic instincts of the Chinese would be seen, for all classes without distinction would mix freely and show mutual respect and courtesy” (Song, 1923: 53–5). Whampoa gained fame also for the dinners he hosted that included Westerners and Chinese at the estate he called “Bendemeer,” the name of a river in Persia mentioned in a poem written in 1817 by Thomas Moore that was popular at the time. There appears to be no record of how Whampoa referred to the garden in Chinese.

Although this photograph was taken in the early twentieth century, all of these shophouses along Chulia Street in Penang were built much earlier, in the nineteenth century.

Tan Seng Poh, Seah Eu Chin, Wee Ah Hood, and Tan Yeok Nee, among other wealthy nineteenth-century Chinese businessmen built between 1869 and 1885 what Singaporeans once called the Four Mansions. Tied to one another to homelands in the Chaozhou area of eastern Guangdong province, they built Chinese-style mansions that survived well into the twentieth century. Today, only the residence of Tan Yeok Nee, the subject of a chapter in Part Two (pages 70–9), remains.

In the 1980s during urban redevelopment in the Kampong Bugis area, the last grand courtyard residence in Singapore in the architectural style of southern Fujian was demolished along Sin Koh Street, which itself was obliterated. This expansive red brick residence, with its swallowtail roofline, which is reminiscent of the home of Tan Tek Kee in Jinjiang discussed above, had been built in 1896 by Goh Sin Koh, a timber merchant who also was in the shipping business. Although records are incomplete, Goh’s grand home at some point was transformed into an ancestral hall for his family and others from their home village in Fujian. The only surviving images of this sprawling and derelict residence were taken in the late 1970s when the building was being used to store lumber.

Penang, Medan–Deli, and Phuket

Penang and Medan–Deli, one on the Malay Peninsula and the other on the island of Sumatra on opposite sides of the funnel-shaped Strait of Malacca, as well as Phuket along the Andaman Sea farther north, have a history of economic and social interdependence. Hokkien traders and settlers reached all three areas in the distant past, well before the late nineteenth century when the numbers of Chinese arrivals increased substantially. In 1786, after the British naval officer Francis Light negotiated with the Sultan of Kedah to cede Pulau Penang, the island of Penang, to the East India Company as a dependency of India for the annual payment of £1,500, Penang began its transformation from being a mere maritime roadstead to a thriving commercial center. Penang began to thrive first, serving as a kind of “mother settlement” that helped spawn and then sustain distant satellites commercial towns like Phuket and Medan–Deli and inland areas on the mainland, such as Sungai Bakap, and in the northern portions of the island of Sumatra where plantation economies thrived.

Legions of Chinese, especially from Fujian but also other areas of China’s southeast coast, as well as Indians, Malays, and Europeans quickly transformed the developing townscape of George Town, named in honor of King George III, and, once it was ceded in 1798, the fertile plains of Province Wellesley, named in honor of the Governor-General of India, across the harbor on the mainland. Indeed, within months of Light’s initial transaction, he was already remarking that “Our inhabitants increase very fast—Chooliahs (Tamils), Chinese, and Christians; they are already disputing about the ground, everyone building as fast as he can.” Eight years later, he boasted (“Notices of Pinang,” 1858: 9; quoted in Purcell, 1965: 244):

Early shophouses in the coastal Sumatran town of Tanjungpura, which was connected to Medan by a railway.

Not too far from the Deli River, the Guandi Temple (Temple to Guan Gong), which was built in the late nineteenth century, has the same structure and layout as a southern Fujian house.

The Chinese constitute the most valuable part of our inhabitants; they are men, women, and children, about 3,000, they possess the different trades of carpenters, masons, and smiths, are traders, shopkeepers and planters, they employ small vessels and prows and send adventures [sic] to the surrounding countries. They are the only people of the east from whom revenue may be raised without expense and extraordinary efforts of government.... They are indefatigable in the pursuit of money, and like the Europeans, they spend it in purchasing those articles which gratify their appetites. They don’t wait until they have acquired a large fortune to return to their native country, but send annually a part of their profits to their families. This is so general that a poor labourer will work with double labour to acquire two or three dollars to remit to China. As soon as they acquire a little money they obtain a wife and go on in regular domestic mode to the end of their existence.

The “Chinese Quarter” in Medan early in the twentieth century reveals wooden shophouses on the right side of the road and masonry ones, most likely built later, on the left.

This Malay-style residence, which is elevated on wooden posts and roofed with attap, was constructed for use by the Chinese supervisor of a plantation in Deli, circa 1885.

Late in the eighteenth century, well before Chinese began to arrive in significant numbers, Light had already seen the potential value of Phuket in Siam, today’s Thailand. Using Phuket’s common name at the time, he commented that “Junk Salong 45 miles long and 15 broad, is a good healthy island, has several harbours where ships may careen, wood and water safe in all seasons, but it will be six or seven years before it is sufficiently cleared and cultivated to supply a fleet with provisions, it is exceedingly rich in tin ore and may be fortified at a small expense; it belongs to Siam. The inhabitants tired of their slavery are desirous of a new master” (“Notices of Pinang,” 1858: 185). Throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth century, shophouses in the style of those built in Penang as well as mansions in what is called Sino-Colonial style were constructed in large numbers in Phuket.

The northeastern coast of Sumatra, which lay across the Strait of Malacca opposite Penang, had received only limited visits by Chinese traders who previously only focused on the potentiality of sites along the east coasts of the strait. Some had come to Laboehan (Labuan) at the mouth of the Deli River, which had been the seat of the Sultan’s power; but there is little evidence of early Chinese settlement there. However, once the Dutch proclaimed their territorial claims to northern Sumatra in 1862, setting in train the opening of the area to large-scale plantation agriculture organized by a variety of European and American firms based upon export crops such as tobacco, rubber, coffee, and oil palm, there was an extraordinary demand for coolie labor that could only be satisfied by immigrants. At first coolies were brought from Penang and Singapore before hundreds of thousands were recruited directly from China and Java using intermediaries who resided in Penang. Because of the insalubrious environment at Laboehan, a decision was made to build a modern planned town at a site called Medan, some 10 kilometers inland, which was connected by rail to the port at Laboehan. By 1917 Medan was described as the “queen city of the island of Sumatra,” “a charming city, brisk and bustling in its business quarters, surrounded by pretty suburbs, with a sanitary system equal to that of any English town. It has two fine hotels, a railway station of handsome architecture, a racecourse, a palatial club, sports ground for football and land tennis, a cinema theatre, and all the modern attributes of an up-to-date centre” (quoted in Buiskool, 2004: 6). Even the Sultan of Deli built an imposing istana or palace, which was designed by a European architect, in Medan.

While Penang began to lose some of its prominence after Raffles founded Singapore in 1819, its role as a regional center continued to expand, especially after it was joined with Malacca and Singapore in 1826 to form the Straits Settlements. Initially, Penang was the capital of this far-flung network governed by the East India Company, but in 1832 the rapidly developing Singapore eclipsed Penang as the seat of government. In 1867 the tripartite Straits Settlements commercial entity became a Crown Colony under direct British colonial administration. Through strategic alliances, which were often based on Chinese dialect relationships, business increasingly was transnational, going beyond the British Straits Settlements to the Netherlands Indies, Siam, Burma, as well as ports in eastern India and southern China. Interestingly, not all of the linkages were by sea. Transpeninsular overland trade routes from Pattani, Nakhon, and Songkhla on the east coast of southern Siam linked Penang on the west coast to Bangkok’s thriving commerce. Merchandise was carried by caravans of elephants in five days along easy pathways that formed a kind of land bridge, a “vein of commerce” of enormous utility, the length of which came to be known as the “Kedah Road” (King, 2002: 96–7).

By the last quarter of the nineteenth century, there were as many as 200 Chinese merchants “plying the seas and accumulating wealth” in the region straddling the Strait of Malacca and beyond, with Penang as the hub (Wong, 2007: 107). The so-called “Penang’s Five Major Hokkien Clans,” Bincheng Fujian wu da xing—Tan, Yeoh, Lim, Cheah, and Khoo—especially, were major players in developing the regional, indeed even transnational enterprises involving tin mining, revenue farming, coolie recruitment, and shipping. Diversifying into the wholesaling and retailing of staple foodstuffs, daily needs, and furnishings made in China and Europe not only met but also stimulated demand by consumers and brought wealth to merchant families. The prosperity generated from these economic activities altered expectations about housing, hygiene, comfort, and education, among other aspects of modernization, in areas where immigrants from Europe, China, India, and elsewhere mixed.

This rambling mansion on Krabi Road in Phuket was built in the middle of the twentieth century by Phra Phitak Chyn Pracha, a Sino-Thai who made his fortune from tin.

As the population swelled in Penang, Phuket, and Medan, shophouses of various types were built and rebuilt to meet the evolving commercial and service needs of residents along newly planned streets that spread beyond the town core. Sumptuous residences and government buildings, some of which were quite grand, as well as Christian churches, also increased in number. As affluent merchants gained wealth from plantation agriculture, mining, and shipping in the mid-to late nineteenth century, bungalows and mansions of substantial proportions and eclectic styles were also built in each of these regions. In addition to the broad range of residential structures, Chinese settlers also continued to renovate existing or build new Daoist and Buddhist temples, which universally were modeled after those in their hometowns in China. Buildings to meet the needs of their thriving clan associations, usually called kongsi, also increased in number. Bricklayers and carpenters from China arrived to erect many of these structures, some of which were constructed using fired bricks and roof tiles carried as ballast on trading ships outbound from China. Because of the richness of the hardwood forests in Southeast Asia, timber was usually sourced locally.

In the sections that follow, examples of each of these housing types are presented. In Penang, a late nineteenth-century shophouse associated with the peripatetic efforts of the revered Chinese leader Sun Yat-sen, is presented as typical of a building typology of great significance (pages 114–19). Chung Keng Quee, one of the principal tin magnates of the Straits Settlements (pages 102–13), and Cheong Fatt Tze, an extraordinary multinational entrepreneur who amassed fortunes from mining, plantation agriculture, banking and shipping (pages 128–39), built in Penang a contrasting pair of mansions that share many underlying themes. One special feature of Chung Keng Quee’s home, as will be discussed later, is that he had a spacious private ancestral hall built adjacent to his home. Constructed as the nineteenth century came to a close, these grand residences evoke the styles of the late Victorian era during a period of increasing global interdependence when eclectic decorative arts styles were in fashion throughout the world. Significantly, in the case of homes discussed in this book, there was a concomitant resurgence of pride by well-to-do Chinese in the culture of their ancestors. For many, it was essential that craftsmen from China were “imported” to design and fabricate multifarious forms of applied ornamentation and furnishings in order to assure authenticity, even as they sought fixtures and art works from Europe to express modernity.

This rundown shophouse along Thalang Road in Phuket was restored recently as China Inn Café & Restaurant.

Deteriorating and restored buildings, each of which remains imposing and said to be in Sino-Portuguese style, are found throughout Phuket.