Читать книгу Edible Pepper Garden - Rosalind Creasy - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеthe edible

pepper

garden

As I approached the fairgrounds, I asked myself how I was possibly going to eat all that chili and not burn up. This was my first chili cook-off, and I was a judge. How much chili does a judge eat? Do the folks make it really hot? I like spicy food, but I don’t have a mouth made of asbestos like some people I know. I had been to wine and produce tastings, but never a chili tasting. How could I possibly clear my mouth from one bite to the next?

I was early for the judging because I wanted to talk with the entrants about what they put in their chilis. As I entered the cook-off area, I was surprised at the festival atmosphere. The lawn was surrounded by dozens of carnival-type booths, all decked out. A couple of middle-aged ladies were cooking away in a booth labeled The Hot Flashes. On the sign for another booth was a giant can of Hormel chili with the international prohibited symbol across it—the Hormel Busters, of course. There were the Heart Burners, Chili’s Angels, Rattlesnake Rick’s, Earthquake Chili, and even a group dressed in camouflage garb proclaiming their chili Rambo Red. Hundreds of visitors were wandering around getting pointers, tasting the chilies, and buying drinks and mouth-watering bowls of chili. What fun!

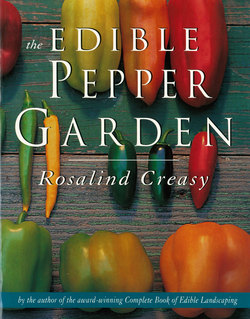

Peppers sweet and hot come in all shapes and colors.

When it came time to judge the chili, I joined twenty or so other judges in a hall. There, the officials explained the procedure. Cups of chili were laid out on a long table with only a number to identify each one. Between all the cups were trays of soda crackers and cut-up pieces of celery. (So that’s how you clear your palate, I thought.) There were also a few bowls of sour cream, used to put out the fire if a chili was too hot. And, of course, there was beer. For guidelines, we were told to ask ourselves first if we would want to eat a whole bowl of this chili. We were to look for depth of flavor—a lasting one—and a chili that wasn’t too salty and that certainly wasn’t sweet. We were to seek a traditional taste. And above all, we were not to talk or make faces. The only communication allowed was a warning to our fellow judges if we ran across a “killer chili”—one that was too hot.

Chilis Angels (above) otter some of their chili to folks attending a San Jose cook-off.

It would be nice to say I had such a sophisticated palate that I picked all three winners, but in fact I liked only one of the winning chilies. It amazed me that most of the chilies were fairly mild, that they varied greatly, but that the winners were quite similar and, furthermore, very salty. The winning chilies were dark red-brown, full of flavor, and smooth in texture.

How did this Yankee, who grew up never eating anything spicier than a gingersnap, wind up as a chili judge? Like many other Americans, for years I had ignored chili and chili peppers of all types. But as my tastes changed and I was exposed to more and more hot Mexican and Asian dishes, I gradually started to enjoy spicy foods. I even began making chili using a commercial chili powder. The result was good, but when my husband brought back separate chili spices from Texas and I started making chili with selected varieties of ground chilies, what a revelation! Chili peppers weren’t simply hot; they actually had complex and varying flavors. This appreciation of fresh ground chilies led naturally to the next step: growing and cooking with fresh green and red chilies of many different varieties. A whole new world had opened up.

This arrangement of peppers to the right was harvested at the Kendall Jackson Winery trial gardens in Santa Rosa, California. It includes over twenty varieties including ‘Yellow Cayennes,’ ‘Hot Cherries,’ ‘Poblanos,’ ‘Purple Beauty,’ pimentos, and many varieties of jalapeños.

all about peppers

For years, Americans were but a ripening away from great red, yellow, and orange bell peppers. Peppers were harvested in their unripe green stage because it was more efficient for farmers. Now we can choose from a rainbow of peppers and they are oh-so-much sweeter and juicier.

All peppers, both hot and sweet, are perennials in the genus Capsicum and, along with relatives such as tomatoes and potatoes, are in the Solanaceae family. Peppers originated in subtropical areas of South America and were eventually spread, probably by birds, over South and Central America. Over time they were transported by people to the far corners of the earth and quickly assimilated into many cuisines, often substituting for black pepper. Over the centuries, countless varieties of peppers have been bred to meet the tastes of many different cultures.

There are five species of peppers used for food, but the vast majority under cultivation today are Capsicum annuum, which includes both sweet and hot types. A few popular exceptions are C. chinense, which includes the notoriously hot habañero, and C. frutescens, which includes tabasco and some of the Asian hot peppers. There are also several wild species. In fact, chili peppers still grow wild in many areas of the southwestern United States through parts of Central America and are harvested by the native peoples there.

Sweet Peppers

Sweet peppers evolved from wild (hot) peppers and were bred for their vegetable characteristics, not for their heat. The sweet pepper most of us grew up with was the green bell pepper. Never the belle of the produce section, it nevertheless had its fans. All that has changed, however, as in the last two decades peppers have been transformed. Americans have fallen in love with peppers. Chili peppers receive the most press and are considered the “sexiest” (they even have their own society), but one look at any supermarket produce section reveals many more flashy sweet peppers than chilies. Since we grew up with only green sweet bell peppers, why, suddenly, can we choose from red, orange, brown, ivory, yellow, and even purple ones? What are these colorful peppers, and where they all come from anyway?

You’re going to have to bear with me here because the answer is a bit involved. First, the easy part. The great majority of green peppers are simply unripe peppers that would turn red if allowed to ripen. Most brown, ivory, lavender, and purple ones, too, are just different varieties of bell peppers, are also unripe, and would eventually ripen to red. Now the tricky part. Some yellow and orange peppers begin as green and turn to yellow or orange when ripe; others ripen to red. However, others start out as yellow or orange and keep their original color when ripe.

As to where they came from, for eons the red ones were but a ripening away from your kitchen. Historically, we Americans have been fairly undemanding about vegetables, and when farmers offered only the green, because they were more efficient to produce and ship, we didn’t clamor for other colors. In other parts of the world, especially in Eastern Europe and Italy, they’ve enjoyed red, orange, yellow, and ivory peppers for ages. (As an aside, Europeans favor elongated sweet pepper varieties over blocky ones.) Some of the new colors, especially the orange, ivory, and lavender ones, are modern hybrids bred to capitalize on the new interest in bell peppers.

Certainly this chameleon aspect of peppers is interesting, but for the cook it has further ramifications. An unripe green or purple bell has a strong pepper taste and is somewhat sour. In contrast, a ripe red pepper has a rich, more complex pepper flavor and a mellow sweetness. Wendy Krupnick, one-time garden manager of Shepherd’s Garden Seeds, said it best: “Unripe bell peppers taste like a vegetable; ripe ones taste more like a fruit.” And as any nutritionist knows, ripe peppers have more vitamins as well.

[terminology]

A note about terminology. The word chili, used alone, can refer to the wonderfully tasty and spicy dish made with hot peppers and tomatoes. However, the word chili is also used to refer to peppers. The spelling of the word denoting the pepper depends on a number of factors; it may be variously written chili, chile, or chilli, as in chili peppers, chile peppers, chilies, or chiles. All are correct, as they are common names derived from various locales. For the purposes of this book, I chose to use the terms chili and chilies.

To experience the color shift as they mature, we laid out three different color stages of peppers, from unripe on the left, to ripest on the right. ‘Cal Wonder’ and ‘Gypsy’ are in the top row; a purple ornamental, ‘Yellow Cayenne,’ and ‘Early Jalapeño’ are in the middle row; and ‘Sweet Banana’ and ‘Golden Bells’ are on the bottom.

Blocky bell peppers are the most popular sweet peppers in America. Some of the red and yellow bells have been around for many years, but the lilac, white, and orange bells have been bred in the last few decades.

Hot Peppers

The hotness of hot peppers comes primarily from capsaicin, a pungent and irritating phenol. This chemical is located in the chili pepper’s placental tissue, which is found in the light-colored veins on the walls of the pepper and around the seeds. Until fairly recently, the average American gardener ignored chili peppers, so our plant breeders and seed people did not give them much attention. Consequently, most of these fiery cousins are less domesticated than the sweet bell pepper.

While there is an expanding collection of selected chilies, and even a few hybrid jalapeños and poblanos, the less-domesticated chilies differ from bell peppers in a number of ways. The less-domesticated ones are often slower to germinate, and some grow more slowly. A few need very warm weather. Others are more disease resistant than most bells. Chili plants are generally taller, more open, and rangier than bells. Some varieties hold their fruits on top of the leaves in a decorative way, but most produce fruits that hang down. Certainly among the most beautiful vegetables, chili pepper fruits can be large or small, and round or elongated. Unripe, they can be green, black, yellow, orange, white, or purple. Like their bell cousins, they ripen through a range of colors including orange, or even brown, but most become red. Chili peppers range in hotness from mild to scorching.

Whenever I talk with gardeners and chefs about chilies, the conversation eventually turns to their heat. And the question always arises, What makes the same pepper variety fiery hot one time but mild another? Most of us have planted the same variety and had it come up mild one year but quite hot the next. In discussing this inconsistency with seed people, I learned that there can be different reasons for the variation. Most agreed that the main reason was climatic differences. A somewhat mild chili pepper, for example, might get hotter than usual if grown under the stress of hot and dry conditions. A large difference, however, would be very unusual. A jalapeño might be milder one year than another, or milder in a wet climate than a dry one, but it would still be quite hot, and a mild chili such as an ancho will never be extremely hot.

Another factor affecting the hotness of chilies involves different strains, or subtypes, of the same variety. All jalapeños are not created equal. A generic jalapeño from the nursery, or ordered from a seed company, can vary widely depending on which strain is offered. (For a discussion of varieties and why they vary, see page 41 in “The Pepper Garden Encyclopedia.”)

Putting aside the above minor variations, what everyone really wants to know is, Which variety is the hottest? A number of tests have been used over the years to determine how hot a pepper is, the oldest being the Scoville Organoleptic Test, in use since 1912 (see page 9 for more information on the Scoville test). Recently the Official Chile Heat Scale has become popular, which rates chilies on a 0 to 10 scale with bell peppers as 0 and habañeros at 10; jalapeños rate 5, cayennes 8, and chiltepíns 9. Craig Dremann has created his own hotness scale, based on his testing, which he includes in his Redwood City Seed catalog to help you choose your peppers.

‘Large Thick Red Cayenne’ is one of many types of cayennes and is very hot.

Throughout much of the American Southwest, wreaths and ristras of chili peppers are hung on doors and from house eaves to signify prosperity.

The aforementioned scales are all based on human perceptions of heat and are all helpful but obviously subjective. More uniform, objective testing has been done at New Mexico State University using a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) machine. Instead of human perceptions, it records the quantifiable amount of numerous capsaicinoids in an individual pepper. While we think of just one chemical as responsible for the heat, in fact, any one hot pepper contains a number of related capsaicinoids, each with its own characteristics. Some sting instantly, while others take time to bite and build slowly. Some affect the tongue, while others burn the back of the mouth. Their flavors differ as well. Some are described as fruity, while others are musky or smoky. The HPLC machine can quantify the chemicals in only one pepper at a time, and because peppers differ from season to season and plant to plant, it really just gives us a ballpark number. Of course, the question still arises, Which is the hottest? According to Dr. Paul Bosland, who has access to this machine, no matter how many chilies he tests, the habañero always tops the scale.

While the question of how hot a pepper might be is fun to discuss, a very hot chili pepper such as the habañero or ‘Tepin’ can actually burn you. Craig Dremann recommends that if you’re going to eat a chili pepper you’ve never had before, you should taste it very, very carefully. When he tries a new pepper, he bites into it very slightly with his teeth, and then gingerly tastes the top of his teeth to see what is happening. He then proceeds gradually to bite through the skin and then finally into the chili pepper itself. He avoids using his tongue and lips until he knows the pepper is sufficiently mild.

No matter which variety you choose, peppers hot or sweet enliven the meal and are beautiful in the garden. As gardeners, we have a fabulous choice of peppers, and the mightiest chef can only sigh and yearn for such a flavor-filled option. The following sections will make all your chili dreams possible.

A bountiful basket of the colorful pepper harvest.

[Scoville Units]

In 1912, Wilbur Scoville, a pharmacologist, developed a test to determine the capsaicin content of a hot pepper. He dissolved exact amounts of chili peppers in alcohol diluted with sugar water and had a panel of at least five tasters rate the heat. The hotness was recorded in multiples of one hundred Scoville units. While obviously subjective, this rating did give a rough idea of how hot a pepper variety might be. Today, we analyze peppers’ heat using more scientific methods, with a high-performance liquid chromatography machine. The machine-produced numbers are then converted to Scoville units.

The chart to the left gives approximate Scoville unit readings for some of the more popular peppers.

| SCOVILLE HEAT SCALE | |

| Pepper Variety | Scoville Units |

| Habañero types | 100,000-300,000+ |

| Chiltepíns | 50,000-100,000 |

| Thai | 70,000-80,000 |

| Cayenne, aji, tabasco | 30,000-50,000 |

| Serrano, hot cherry | 15,000-30,000 |

| Jalapeño, Fresno | 5,000-15,000 |

| Ancho, pasilla | 1,000-1,500 |

| ‘NuMex Big Jim,’ ‘Anaheim’ | 100-500 |

| Sweet bells, pimientos | 0 |

the Creasy pepper gardens

My 1990 pepper garden took over the entire front yard and was interplanted with flowers for drying and for beauty. Both were harvested at about the same time and the bouquets were hung from the garage rafters to dry. The peppers were enjoyed fresh of course, but the bulk was either given to a food bank, frozen, or dried in the dehydrator.

I have an unusual vegetable garden—it’s smack dab in my suburban front yard. Twenty-five years ago, I was forced to garden “around front.” Our backyard was hopelessly filled with large trees—a redwood, pines, and a fruitless mulberry—and between the shade and the root competition, a vegetable plant didn’t have a chance. In those days “veggiescaping” was considered verboten, and when I first planted vegetables around front, I felt forced to plant them surreptitiously in a narrow strip along the front lawn—hiding them among tall flowers. Fortunately, I was studying landscape design at the time, and it wasn’t long before it occurred to me that my frilly lettuces, ruby chards, most herbs, eggplants, and my pepper plants were every bit as beautiful as many so-called ornamentals and I could grow them in full view. Of course, planting them in long boring rows and covering the plants with old bleach-bottle cloches wouldn’t cut it in the front yard, but well-grown vegetables planted in decorative patterns, or interspersed with flowers, I knew would be lovely.

It was in this same time frame that I was developing my concept of edible landscaping, which was later to become a book; thus my front flower border became part of my many design experiments. For a few years, I experimented with background borders of artichokes, chard, tall chili pepper varieties, and beans; middle borders of sweet peppers, eggplants, carrots, and bush peas; and front borders of parsley, strawberries, lettuces, and small ornamental peppers. As the years progressed, I found I needed more and more space for vegetables; the long narrow beds weren’t big enough and they limited my designs. So, every year the beds got larger and were reconfigured and the lawn got smaller. Finally, about fifteen years ago, the genie was completely out of the bottle, the remaining lawn came out, and I appropriated the entire front yard to grow vegetables and herbs to research varieties for my book Cooking from the Garden. That year, I trialed 110 varieties of vegetables in the front yard, and both my husband and the neighbors thought the garden quite wondrous. Once convinced I could make a vegetable garden a social success, I have since grown over thirty different theme vegetable and herb gardens in our front yard. (Since I garden in USDA Zone 9, that includes both winter and summer plantings.) One season, I planted a Native American garden, yet another year I chose a salad theme, and so on.

The 1990 Pepper Garden

In the summer of 1990, I decided that while over the years I had planted many pepper varieties, it was time to explore peppers in depth, and I planned a pepper garden in the beds near the driveway where they would get lots of heat. To intersperse color among the pepper plants, I selected many different types of flowers that dry well for bouquets.

In January, I ordered seeds of twenty varieties of peppers, six special dry flowers, and some choice cutting flower varieties, all by mail. Pepper plants take a long time to get sizable enough to plant outside, so I started them in mid-February, about ten weeks before I planned to plant them outside—namely, in early May. This is at least a month earlier than I start my tomatoes and most of my other vegetables and flowers. I started most of the pepper seeds in potting soil in flats, others in quart containers. I planned for a plant each of most of the bells and hot chilies and a half dozen ‘Anaheims’ and two pimientos so I would have enough peppers to roast. To get the seeds to germinate quickly, I placed them in the oven of my gas stove, which has a pilot light that maintains a temperature of about 80°F when I leave the door ajar. In reading the germination information on the seed packages of both ‘Tepin’ and ‘Chili D’Arbol,’ I noted that instead of sprouting in the usual seven to ten days, they can take from fourteen to twenty-one days; therefore I planted them in their own container.

As soon as the pepper seedlings emerged, the containers were moved onto my kitchen table and under florescent lights. (Two varieties failed to germinate. I assume, because eighteen varieties germinated easily, that the seeds of the ones that didn’t were either too old or hadn’t been handled properly by the grower or seed company.) After the seedlings produced their first set of true leaves (the leaves that appear after the first seed leaves), I moved each plant into its own four-inch-square container and fertilized them with quarter-strength fish emulsion. (You’re right, the kitchen smelled awful for a day.) A month or so later, I moved them up into one-gallon containers and repeated the fertilizer. By mid-April, the plants were ready to go outside, and I lined the containers up along an east-facing garage wall to get them acclimatized to the sun and nighttime temperatures. I also found a few pepper plants at the nursery that I wanted to try, and added them to my collection, which now numbered twenty-one.

In early May, my crew and I planted out the peppers. After six years as a vegetable garden—one that had been mulched and babied every year—the soil they were to be grown in was already in great shape, filled with organic matter, and the beds and paths were in place. The peppers were to be planted in three long rows separated by existing brick paths. Flowers—namely, different colors of statice and gomphrenas and tall varieties of zinnias, cosmos, and lavatera—were spotted around. Drip-irrigation lines were already in place along the beds, and the individual strips of laser line were snaked around and among the transplants and held in place with ground staples.

We had a cool but sunny May and early June, and the peppers were off to a slow start. Once the soil finally warmed up in mid-June, we applied a few inches of compost for a mulch, and in the heat most of the peppers finally took off. The peppers that lagged behind were some of the sweet bells. By mid-August, I had plenty of green jalapeños, serranos, and ‘Anaheims’ and a few ‘North Star’ and ‘Yolo Wonder’ green bells to harvest, but it wasn’t until mid-September that the bulk of the peppers started to really produce. And produce they did.

I wouldn’t say I had a great harvest, but I had all the peppers I could possibly use and then some. Twenty-seven plants produced baskets and baskets of peppers, and the harvest lasted through October. Most of the bells were used in salads, peperonata, on the grill, and in numerous soups and stews. A lot were also shared with friends, family, and the local food bank. The very hot peppers—‘Tepin,’ ‘D’Arbol,’ and ‘Thai Hot’—produce lots of peppers, and a little goes a long way. Most of these, and all the different paprika peppers, I dried in my dehydrator to be enjoyed as seasoning throughout the year. To keep them safe from the pantry meal moths that I had in abundance (I found out later that there are pheromone traps that control these kitchen pests), I put the whole dried peppers in plastic freezer bags, labeled them, and put them in the freezer. I had planted six ‘Anaheim’ and two pimientos, and they produced four big grocery-store bags full of peppers over a six-week period. My daughter-in-law Julie and I spent hours every weekend roasting, peeling, and cutting them into strips so that they could be frozen in freezer bags. Although we said at the time that we would probably never use them all, both of us ran out of them by June. (We both got spoiled because all winter long we were able to make a great meal quickly; from roasted pepper soup for Christmas to a lunch of bean burritos; all we needed to do was reach in the freezer.)

Bell peppers, paprikas, and lots of New Mexico types and hot chili varieties filled my harvest baskets from late August to late October.

As we pulled the plants out in late fall, I analyzed their health and how the individual varieties had performed and tasted. I came to the conclusion that most of the bell pepper plants looked sparse and didn’t produce as they should have (not that we needed any more), and none looked as vigorous as the many chilies. Further, some of their lower leaves were very pale. In my experience, that means not enough nitrogen, and while all the books I’d read said not to feed them heavily, the next time I planned to give them more nitrogen. For grilling, I most liked the flavor of the anchos and pimientos, but I was disappointed in the productivity and flavor of the purple bells—when I served them in their unripe purple stage, they tasted like green bell peppers. The biggest surprise was the flavor of the ‘Almapaprika’ pepper; it was sweet, hot, and the essence of pepper. This thick-walled, slightly hot pepper was bred in Hungary for eating fresh, and it tastes terrific that way, but I also dried it for the spice paprika. Because of its thick flesh, it had to be cut in thin slices and dried in a dehydrator, and when it was ground it tended to clump, but who cared, what flavor!

The 1998 Pepper Garden

The 1990 pepper garden was so much fun, I decided to grow another, but this time in a whole new space out by the street because the soil in the driveway beds had become contaminated with nematodes (tiny parasitic critters that invade a plant’s root system and stunt their growth), to which most peppers are susceptible. The drainage was poor in the beds along the street, so I had wooden planters built and a commercial soil mix delivered to fill them. Fortunately, a friend was visiting at the time who is a soil-consultant, and when I told him I usually had problems when I imported soil, he offered to test it. (When you purchase soil from garden supply houses, you seldom know the quality because it depends on where the soil was dug and what was mixed into it.) The analysis showed that the new soil was extremely high in sulfur and boron and practically off the chart in potassium. On the good side, the pH was 7.5, and the soil was high in organic matter and nitrogen. You can see that if I’d had no soil test and added a standard balanced fertilizer, I would have added even more potassium and nitrogen, and my peppers would have been stunted or would not have bloomed because of the excess nitrogen. My soil guru prescribed a specific amount of limestone to lower the potassium and tie up excess boron. We added the amendment and mixed it in and added no other fertilizers.

It was the year of El Nino and that spring we had record-breaking rain—including thirty days of rain in a row for a total of 40 inches—unheard of in our arid climate, which averages 15 inches a year. Needless to say, it was a bad spring for getting peppers off to a good start, and I lost 90 percent of my seedlings—all but a few ‘Golden Cayennes’ and ‘Figaros.’ I had started the peppers in February as usual, and by April they were big enough to be transplanted to one-gallon containers and moved outside. There, they languished for six more weeks in cold wet weather. (Next year, I get a cold frame.) By the time we were able to plant in mid-June, most of the peppers either had succumbed or looked too pathetic to plant! I decided to abandon my pepper project. But then a trip to a few nurseries yielded a surprising number of interesting pepper varieties. Counting a lovely unnamed yellow ornamental pepper that I purchased at midsummer in a florist’s shop, I ended up with one plant each of seventeen varieties and two plants each of the cherries, ‘Figaros,’ and ‘Golden Bells.’

My 1998 pepper garden was created in raised beds out at the street and welcomed all who visited. The driveway beds I had used before were planted with marigolds to control a nematode infestation. The rest of the yard was filled with vegetables and herbs.

The raised beds along the street (above), were filled with peppers. The varieties growing in the bed include ‘Figaro’ pimento, ‘Hungarian Wax,’ ‘Italian Long,’ ‘Thai Hot,’ ‘Golden Bell,’ and an unnamed yellow ornamental pepper growing in a container. Two easily grown bell peppers, ‘Gypsy’ and ‘Cal Wonder,’ (below) grow in another bed.

There is considerable evidence that marigolds of all types help deter nematodes. And because most varieties of peppers are quite prone to nematodes, we interplanted the peppers with dwarf marigolds to be cautious. (The driveway beds were also planted with twelve different varieties of marigolds.) When we pulled the gardens out in the fall, there was no nematode damage on the pepper roots (nematodes cause knotlike swellings on the roots and generally deform them) and the driveway beds seemed clear as well.

Considering the very late start in planting the peppers and the questionable soil mix, the pepper garden did well. It produced baskets full of peppers, again far more than we could use. The stars this season were the sweet ‘Figaro’ pimientos; the ‘Golden Bells,’ which were enormous, sweet, and plentiful; the big, juicy, and flavorful ‘Jalapeño Frienza’; and the cherry peppers. The cherries were new to me, and I really enjoyed them pickled and stuffed for “shooters” (see page 78). I missed being able to roast our usual poblanos and ‘Anaheims’ from seasons past; and we still don’t fully appreciate habanero peppers because they’re too hot! All things considered, though, the peppers really came through, the harvest was delightful, and it was such a beautiful garden, cars would slow down to check it out. Who says you can’t landscape with veggies?

1990 Pepper Garden: Twenty-Three Varieties

Sweet Peppers

‘Big Red’

‘Chocolate Bell’

‘Culinar’

‘Golden Summer’

‘North Star’

Paprika

Pimiento

‘Purple Beauty’

‘Sunrise Orange’

‘Vidi’

‘Yellow Bell’

‘Yolo Wonder’

Hot Peppers

‘Almapaprika’

‘Anaheim’

‘Chili D’Arbol’

Jalapeño

‘Mexibell’

‘New Mexico’

‘NuMex Big Jim’

‘Paradicsom Alaku Zold Szentesi’

Serrano

‘Tepin’

‘Thai Hot’

1998 Pepper Garden: Twenty Varieties

Sweet Peppers

‘CalWonder’

‘Figaro’

‘Golden Bell’

‘Gypsy’

‘Italian Long’

‘Orange

King’

‘Shishitou’

‘Sweet Banana’

Hot Peppers

Chiltepín

‘Fiesta’

‘Golden Cayenne’

Habañero

Jalapeño

‘Jalapeño Frienza’

‘Red Cherry’

Serrano

‘Thai Dragon’

‘Thai Hot’

‘Variegata’

‘Yellow

Ornamental’

how to grow peppers

Peppers are substantial plants and many, including the New Mexico types and bells, need sturdy supports or they tend to fall over in the wind. A path between rows gives access to the plants for weeding, maintenance, and harvesting.

Like every gardener, I must admit I succumb now and then to impulse buying at the nursery. However, like most gardeners who have spent much time growing peppers, I have learned the hard way that my most successful pepper plantings result from planning and doing my homework. So, before I (or you) touch shovel to soil, here are two critical questions that need to be answered:

1. Where is the best place in the yard for my peppers?

2. What are the best pepper varieties for my climate?

When you have the answers to these two questions, you are well on your way to growing a bounty of beautiful peppers.

Planning Your Pepper Garden

Peppers are tender perennial plants, and only a few varieties have the slightest tolerance for frost. Consequently, most gardeners grow them as warm-weather annuals. They need warmth and sunshine and good soil drainage. Find a place in your garden with at least 8 hours of sunlight a day (except in extremely hot areas, where afternoon or some filtered shade is best). Then test the soil to make sure it drains well. Many of the diseases that affect peppers are caused by poor soil drainage because peppers are quite susceptible to root rot. If you think you might have a problem, the section “Preparing New Garden Beds and Adding Soil Amendments” on page 19 gives information on testing your soil for drainage.

Peppers needn’t be alone in their perfect spot. You can add them to a vegetable garden, interplant a few peppers among your ornamentals—particularly your summer annual flowers—or design a new garden. In addition, many peppers do wonderfully in containers or in large planter boxes—which may be necessary if your soil drainage is poor or your soil has fungus or nematode problems.

If you become excited enough to plan a fabulously large pepper garden, there are design considerations, including bed size, paths, and maybe even fencing. Once you plan a garden of a few hundred square feet or more, you need to provide paths, and the soil needs to be arranged in beds. Beds are best limited to 5 feet across, which allows the average person to reach into the bed to harvest or pull weeds from both sides. Raised beds of mounded soil (6 to 8 inches high) are great for peppers because they warm up more quickly in the spring than flat beds do, and they drain well too. Paths through any garden should be at least 3 feet across to provide ample room for walking and using a wheelbarrow. Protection is often needed, so consider putting a fence or wall around the garden to give it a strong design and to keep out rabbits, woodchucks, and the resident dog. Especially tall fences, over 8 feet in height, are needed if deer are a problem because they are great jumpers, and once over, they love to nibble pepper plants to a nubbin, even the really spicy ones!

The number of pepper plants you plan to grow needs thought. Home gardeners don’t need a full flat of jalapeños, no matter how good a deal they get at the nursery. Better to put in two or three plants of a few varieties each year until you find those you most enjoy and that grow best in your garden. With many pepper seasons under my belt, I find that to match the way I cook, and with the number of peppers I give away, I need a minimum of three plants each of pimiento and ‘Anaheim’-type peppers for roasting; a few plants of yellow, orange, red, and lilac bells for colorful salads and soups; a few Cuban and ‘Italian Long’ sweet peppers for frying; a few paprika peppers for drying; three or so plants of jalapeños for chipotle and using fresh; and only one plant each of the blazo serrano, chiltepíns, de árbol, and habanera types because a little heat goes a long way in my family.

Selecting Pepper Varieties

When you choose your peppers, consider not only your dinner table, but also your climate, growing season, sun exposure, and local pests and diseases. You can save yourself much grief by growing the varieties proved best for your region. In the “The Pepper Garden Encyclopedia,” I have noted, whenever possible, the regions where a variety usually does best and where it may have problems. Check also with your local master gardeners’ organization or with the closest university extension service. I realize, of course, that it is often in a gardener’s nature to want to experiment. When you do, it helps to keep good records so that you can repeat your triumphs.

As a general rule, if you are a beginning gardener and looking for sweet peppers with the least problems, choose peppers that produce the smaller fruits because some of the very large bells need optimum conditions to produce well. Some excellent sweet peppers that have been bred for short seasons, such as ‘Gypsy’ and ‘North Star,’ are perfect for beginning gardeners. Gardeners in northern climates and high elevations also need to look for peppers that will tolerate cooler temperatures and/or short-summer growing seasons. Gardeners in hot, humid areas require plants that tolerate diseases, heat, and humidity. See pages 31 and 32 for information on growing peppers under those conditions. Also remember to look at the days-to-maturity numbers and select peppers that will fit into your growing season. (Days to maturity means the number of days it takes a transplant six to eight weeks old to reach a mature green stage. It does not mean from time of seeding. An additional two to six weeks, depending on variety, are usually needed for the pepper to ripen fully.) I always allow leeway because actual days to maturity will vary with the weather. Cool nights, in particular, slow ripening.

Jody Main, my garden manager, shows off the pepper harvest from our 1998 garden.

Certain types of peppers grow better in particular areas. Some of the wild chiltepíns, for instance, are triggered to bloom when the days get short in early fall, and in a short-summer area you won’t get peppers before frost hits. Further, according to pepper gurus Dave DeWitt and Paul Bosland, in The Pepper Garden, “...the New Mexican varieties grow well in the Southwest but not that well in the Northwest and Northeast. Bells and Habañeros do not grow as well in the Southwest as they do in other regions.” In sections to follow, I address the particular challenges of growing peppers in cooler, short-summer regions as well as very hot ones.

If you are lucky, or if you only want to grow a few red bell pepper plants and a generic jalapeño, say, you may be able to obtain your pepper plants locally as nursery-grown transplants. If, however, you become a certifiable “chili-head,” or if you live in a climate that is borderline for peppers, you will need to obtain your plants or seeds by mail order to get a good, much less a great, selection. Fortunately, peppers are quite easy to start from seed. Most seed companies carry a few interesting pepper varieties, but others specialize in peppers and offer a lifetime of choices. See the Resources section, page 102, for numerous recommended seed and plant sources.

Preparing New Garden Beds and Adding Soil Amendments

Let’s assume that you’re hooked on peppers, and planting a variety here and there no longer fills the bill. You now want to grow a pepper garden with many different types. How do you proceed? First you choose a very sunny spot and prepare the soil. If you are one of the few gardeners on the planet with a vacant piece of beautifully loamy soil with good drainage, it’s a snap. You just mark out the rows, turn under a little compost, form the paths, and plant. If you’re like the rest of us mere mortals, however, you have to start from scratch. This means removing a piece of lawn or removing large rocks and weeds. If you’re taking up part of a lawn, the sod needs to be removed. If it is a small area, this can be done with a flat spade. Removing large sections, though, warrants renting a sod cutter, If the area is a weed patch, unfortunately, you will need to dig out any perennial weeds, especially perennial grasses. It’s a pain, but you really do need to sift and closely examine each shovelful of soil for every little piece of their roots, or they will regrow with a vengeance and crowd out your pepper plants. Once the lawn, rocks, and weeds are out, and when the soil is not too wet, you need to spade over the area. If your garden is large or the soil is very hard to work, you might rent a rototiller, When you put in a garden for the first time, a rototiller can be very helpful. However, research has shown that continued use of tillers, or regularly turning the soil over by hand, is hard on soil structure and quickly burns up valuable organic matter if done repeatedly.

Now it’s time to take note of what type of soil you have and how well it drains. Is it rich in organic matter and fertility? Is it so sandy that water drains too fast? Or is there a hardpan under your garden that prevents roots from penetrating the soil or water from draining? Hardpan is a fairly common problem in areas of heavy clay, especially in many parts of the Southwest with caliche soils—a very alkaline clay. You need answers to such basic questions before you proceed because peppers grow best with as little stress as possible and their roots are prone to root rot in waterlogged soil. If you are unsure how well a particular area in your garden drains, dig a hole there, about 10 inches deep and 10 inches across, and fill it with water. The next day fill it again. If it still has water in it 8 to 10 hours later, you need to find another place in the garden that will drain much faster, amend your soil with a lot of organic matter and mound it up at least 6 to 8 inches above ground level, or grow your peppers in containers. A very sandy soil, which drains too fast, also calls for the addition of copious amounts of organic matter.

Find out, too, what your soil pH is. Nurseries have kits to test your soil’s pH. (The most reliable soil tests are done by soil-testing labs. For recommendations, call your local university extension service or ask at the nursery. In addition to giving you the pH, they can also analyze your soil type and nutrient levels at quite a reasonable price. This will give you a much better idea of the amounts and kinds of nutrients it needs.) Peppers need a pH between 6.0 and 8.0 and grow best between 6.7 and 7.3. An acidic soil below 6.0 ties up phosphorus, potassium, and calcium, making them unavailable to plants; an alkaline soil tends to tie up iron and zinc. As a rule, rainy climates have acidic soil that needs the pH raised, usually by adding lime, and arid climates have fairly neutral or alkaline soil that needs extra organic matter to lower the pH.

Most soils need to be supplemented with organic matter and nutrients. The big-three nutrients are nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K)—the ones most frequently found in fertilizers. Calcium, magnesium, and sulfur are also important plant nutrients, and all plants need a number of trace minerals for healthy growth, among them iron, zinc, boron, copper, and manganese. Again, a soil test is the best way to see what your soil needs.

For peppers, most soils will benefit from an application of 4 or 5 inches of compost, 1 or 2 inches of well-aged manure, a phosphorus source such as rock phosphate or bone meal, and kelp meal to provide trace minerals and potassium. If you have done a soil test, you will know more precise amounts. (In future years, you will be able to decrease the amount of additives.) If a soil test indicates that your soil is too acidic, it’s necessary to “sweeten” your soil with applications of finely ground dolomitic limestone. (Avoid hydrated lime, quick lime, and slake lime.) To determine the amounts of phosphorus source, kelp meal, and lime, follow the directions on the packages. (If you wish to add fresh manure, it’s best to add it in the fall because it needs a few months to decompose. In that case, wait until spring to add any additional compost and fertilizers.) Add a few more inches of compost if you live in a hot, humid climate where heat burns the compost at an accelerated rate or if you have very alkaline, very sandy, or very heavy clay soil.

Good advance planning makes for a more productive and healthier pepper garden.

All vegetables need nitrogen for healthy growth. For peppers, how much nitrogen you add is tricky. Peppers grown in a soil overly rich in nitrogen give you lush leafy growth but not much, if any, fruit. On the other hand, with too little nitrogen, the leaves are small and pale, the plants produce few fruits, and those produced are subject to sunscald because the leaves are too small to cover them. According to the majority of gardening books now available, on most soils, aged manure supplies sufficient nitrogen to get peppers growing well. I would agree with that advice when it comes to planting small chilies like chiltepíns, serranos, or de árbols. But my experience with most of the big bells and most hybrids, in particular, has shown me that they need ample amounts of nitrogen. I always scratch into my already fairly rich soil, a handful of blood meal around each plant when I transplant them, and my plants produce a lot of large fruit and lush leaves. Since establishing this routine, I’ve spoken with a lot of seed people and professional growers on the West Coast and they all agree. They all give extra nitrogen to their big bells and hybrids to make sure the peppers get off to a strong start. (Maybe most of the pepper information comes from East Coast growers, and it’s different there.) If you have very sandy soil or one unusually low in nitrogen, I would certainly add an organic source of nitrogen such as fish meal, blood meal, or chicken manure when transplanting your peppers.

Once the plants are growing well and the first fruits are set, most growers agree that all peppers need a supplemental fertilizing with nitrogen to assure a continual supply of healthy leaves. (See “Maintaining Your Peppers,” on page 24.) Experiment in your own garden and see how much nitrogen your peppers need. If your soil is already a very rich loam or otherwise high in nitrogen, then nitrogen fertilizer may not be needed. All in all, in my experience, I have found peppers to need more nitrogen than their cousins the tomatoes, which are infamous for not fruiting when overfed. The goal is to give your peppers enough nitrogen to have a good covering of healthy green leaves but not so much that you grow pepper “trees” with little or no fruit. For an even more in-depth discussion of the pros and cons of nitrogen for peppers, see “Nutritional Deficiencies” in Appendix B, page 99.

Potassium, and especially phosphorus, fertilizers work best when incorporated into the root zone. When you add them, sprinkle them evenly over the soil and incorporate them thoroughly by turning the soil over with a spade, working them, and any mineral and organic amendments, into the top 6 to 10 inches. Nitrogen fertilizers, on the other hand, quickly leach out of the root zone and into underground water sources. They are best sprinkled over the soil just before or after planting and lightly scratched into the surface.

Once all the amendments have been incorporated, grade and rake the area. You are now ready to form the beds and paths. Because of all the added materials, the beds will now be elevated above the paths—which further helps drainage. Slope the sides of the beds so that loose soil is not easily washed onto the paths. Some gardeners add a brick or wood edging to outline the beds. In addition, some sort of gravel, brick, stone, or mulch is needed on the paths to forestall weed growth and prevent your feet from getting wet and muddy.

Starting from Seed

Peppers need a long growing season—up to 120 days from seed to maturity for some varieties. The seeds must have warm soil in which to germinate, and seedlings need warm temperatures for growth. It is imperative in most regions to start your plants indoors and move them out into the garden only after the weather has warmed. Starting seeds inside also gives seedlings a safe start away from slugs, birds, and cutworms.

Start your seeds, in clean flats, peat pots, or other containers with drainage holes, eight to ten weeks before you plan to set them out in the garden. You do not want to transplant them before the soil is reliably warm, which is probably May in much of the country but much earlier in warmer areas, such as along the Gulf Coast and low deserts. In my USDA Zone 9 climate, we have no frosts after early March, but it is May before the weather gets consistently warm, so I start most of my peppers in the middle of February, earlier for some of the slow-growing wilder varieties. Folks in the warmest winter climates often start their peppers in January. I seed mine in either the plastic pony packs that I recycle from the nursery, or in compartmentalized Styrofoam containers variously called plugs or speedling trays (available from mail-order garden-supply houses). Whatever type of container you use, the soil should be 2 to 3 inches deep. Any shallower and it dries out too fast, and any deeper is usually a waste of seed-starting soil and water.

All containers, equipment, and surfaces should be clean. If you have had a history of damping-off, a fungal disease that kills seedlings at the soil line, then disinfect everything as well. Also, if you are a tobacco user, wash your hands well with a strong soap or disinfect them with rubbing alcohol. Tobacco products may harbor tobacco mosaic virus, which can be passed on to your seeds and plants.

Make sure to use a loose, water-retentive soil mix that drains well. Good drainage is important because soil kept too moist can lead to damping-off disease. Resist the temptation to use garden soil. Commercial starting mixes are best since they have been sterilized to remove weed seeds and fungus diseases; however, the quality varies greatly from brand to brand, and I find that most lack enough nitrogen, so I water with a weak solution of fish emulsion when I plant the seeds and again a few weeks later. (Some sources claim that early fertilizing with nitrogen encourages damping-off disease. I have not experienced this, but if you have had this problem, wait until your seedlings are established before fertilizing with a nitrogen fertilizer.)

Renee’s Garden seed company offers a mix of three varieties of cayenne peppers—red, yellow, and purple—all in one package. She dyes them before packaging so you can tell which seeds will produce what color pepper.

Fill your containers with potting soil and smooth the soil surface. (Some gardeners like to premoisten the soil.) Plant the seeds about inch deep and 1 inch apart. Pat down the seeds, and water carefully and lightly to settle the seeds in. With a ballpoint pen or permanent marker, write the name of the species or variety and the date of seeding on a plastic or wooden label and place it at the head of each row.

Keep the seedbed moist but not soggy. Water gently with lukewarm water sprinkled from a watering can, or use a turkey baster to apply the water. Some growers like to cover their seeded containers loosely with plastic, in which case the containers do not need to be watered as often, but you must watch them closely and remove the plastic as soon as germination starts. Germination rates tend to be better when seedbeds are watered from above than when the containers are set in water to be absorbed from below. Bottom watering tends to keep the soil too cool.

Pepper seeds usually germinate best when the soil temperature is in the range of 70°F to 80°F. (They can tolerate higher temperatures, from 90°F to 100°F, and may even germinate faster at those temperatures, but the number of seeds that germinate is usually lower.) Putting the seed trays on the top of your refrigerator may help. However, most gardeners have the best results by using heating cables under their seedling trays. These heating systems need a thermostat to control the temperature (some systems include one). These are available from garden-supply houses or can be ordered from many of the suppliers listed in the Resources section. I don’t normally use propagation mats, because I get great results by putting my seed trays in my gas oven with the door ajar, where the pilot light keeps the seed-starting soil in the preferred temperature range. This method does not work with the newer gas ranges that do not have a pilot light.

Seedlings a few weeks old have been thinned and fertilized.

The peppers are moved into two-inch containers once they develop true leaves and the faster-growing ones are moved up to one gallon pots. At this stage they are almost ready for planting and can “harden off” in the cold frame.

Check your seed containers every day for germination and moisture content. The seeds of some pepper varieties are slow to germinate, and some may need special treatment—especially if you are starting seed from wild plants. If saving seed yourself, make sure the pods have fully matured before harvesting the seed. If germination rates are still low, or the seeds take longer than two weeks to germinate, you might try soaking the seeds in warm water for 2 or 3 days before planting; or soaking them in a 10% bleach solution for 5 minutes and then rinsing them well.

Once your seeds have germinated, it’s imperative that they immediately be given a quality source of light; otherwise, the new seedlings will be spindly and pale. A greenhouse, cold frame, sun porch, or south-facing window with no overhang will suffice, provided the area is warm (about 70°F during the day and 60°F at night), receives plenty of light, and is not drafty. Or you can get very good results by using cool-white fluorescent lights, which are available from home-supply stores or from specialty mailorder houses. The lights are hung just above the plants for maximum light (no farther than 3 or 4 inches away) for 16 hours a day and are raised as the plants get taller.

Fertilize your seedlings weekly with a quarter-strength solution of fish emulsion, and continue to water them gently. Once all your seedlings are up and have two sets of leaves, you can let the surface (about 1/2 inch) of the soil dry out between waterings. Test with your finger to see how moist the soil is. Overwatering can encourage damping-off.

If you have seeded thickly and have crowded plants, thin out the weaker ones. Thinning is important because crowded seedlings do not have room for sufficient root growth. It’s less damaging to do the thinning with small scissors. Cut the little plants out, leaving the remaining seedlings an inch or so apart. Once seedlings have at least two sets of true leaves (the first leaves that sprout from a seed are called seed leaves and usually look different from the later leaves), move the seedlings up to a larger container, such as a 4-inch pot.

Transplanting Your Peppers

Once the peppers you have moved into 4-inch pots are 3 to 4 inches tall and have several sets of leaves—and the weather is warm—transplant them into the garden. Ideally, the peppers should be just at the bud stage and the weather nicely warm. (They should not have open flowers. If they do, pinch the flowers off when transplanting them.) I know from experience that if I get too anxious and set the peppers out too early, when the weather and soil are too cool, the plants just sit there waiting for warm weather, become stressed, and often don’t catch up all season. The ideal time to transplant peppers is when all danger of frost is past, nighttime temperatures are reliably in the mid-50°F range, and the soil has warmed up.

If warm weather has not yet settled in and your peppers are ready to be transplanted, move them to larger containers (at least 1-gallon size) while you wait for the weather and soil to warm. Some gardeners with superior growing conditions, in a greenhouse or such, deliberately start their seeds early to extend their short growing season, and move their plants up to ever larger pots until weather permits putting them outside.

When transplanting peppers out into the garden, first prepare the soil well by working in lots of organic matter and adding organic fertilizers.

Make a hole and place the transplant so it will be at soil level.

Put in a label, and gently press down around the plant. If you are using drip irrigation, install it at this time.

Young plants started indoors should be “hardened off” before they are planted in the garden. This means placing the containers outside in a sheltered place a few hours a day for a week or two, leaving them a little longer each day to let them get used to the differences in temperature, humidity, and air movement. A cold frame is a good holding area for hardening off seedlings. Turn off the heating cable and open the lid more each day.

Occasionally I buy pepper transplants from local nurseries. Before setting these or home-grown transplants out in the garden, I check to see if a mat of roots has formed at the bottom of the root ball. If it has, I remove it or open it up so the roots won’t continue to grow in a tangled mass. I set the plant in the ground at the same height as it was in the container, pat the plant in place gently by hand, and water each plant in well to remove air bubbles. (I never have problems with cutworms that destroy young seedlings by girdling the plant at the base, but if I did, I would place cardboard collars made from paper-towel tubing around the stems to protect them when I planted the peppers.) I space plants so that they won’t be crowded once they mature. When peppers, or any vegetables, grow too close together, they become prone to rot diseases and mildew. (On the other hand, gardeners in hot arid or high-altitude areas can benefit from planting peppers closer together because the overlapping foliage protects the fruits on nearby plants from sunburn.)

I plant most pepper varieties about 2 feet apart, in full sun. Small, short ornamental peppers like ‘Fiesta,’ ‘Variegata,’ and ‘Super Chile’ I plant 1 foot apart and in front of larger varieties, and the spreading tall cultivars, like ‘Bolivian Rainbow’ and wild chiltepíns, I plant 2 1/2 feet apart and behind shorter varieties. I water the plants well at this point, sprinkling the soil gently for three or four applications, letting the water be absorbed between waterings. If I’m planting on a very hot day or the transplants have been in a protected greenhouse, I shade them with a shingle, or such, for a week or so, placed on the sunny side of the plants. If the weather turns cool, I place floating row covers over the plants. Once they are planted, I install my irrigation laser or ooze tubing—see “Watering and Irrigation Systems,” page 93, for more information—and if the soil is warm I mulch with a few inches of organic matter. I keep the transplants moist but not soggy for the first few weeks.

Most pepper plants benefit from staking, which I do soon after planting. I have found that peppers in general are brittle and their branches break readily. The taller plants with large peppers, in particular, often lean over from their own weight, and their branches are easily broken by wind or the weight of the fruit. To support them I use recycled wooden stakes, but wire cages, or constructed wooden cages, also work. When using a stake and twine on any type of plant, I apply the twine in a loose figure eight, with one half of the eight around the stake and the other around the plant’s stem. I try not to bunch the foliage when tying twine around a plant, as this can cause disease due to lack of air around the leaves. I also avoid tying the twine tightly around the stems because that tends to strangle the plant as the stem grows larger. In addition, a plant will be stronger if it is allowed to move some with the wind.

Maintaining Your Peppers—Watering, Fertilizing, Weeding, Mulching

As a rule, peppers need to grow rapidly and with few interruptions in order to produce well with few pest problems. Once the plants are in the ground, monitoring for nutrient deficiencies, drought, and pests can head off problems. It helps to keep the beds weeded because weeds compete for moisture and nutrients. Some pepper experts suggest pinching off the first blossoms on each plant, which is said to encourage the production of more fruit in the long run. Sometimes I do that, other times I don’t have the time or can’t bear to put off the harvest. I’ve yet to document the differences.

In normal soil, peppers usually need a supplemental feeding of organic fertilizer soon after the first fruit has set. Apply a balanced organic vegetable fertilizer or an organic nitrogen fertilizer (such as fish meal, fish emulsion, or blood meal) according to the directions on the package. Scratch dry fertilizers into the soil around the plants and water in well.

Once the young pepper is in the ground, water it in gently. I usually apply the water at least three times to make sure the whole root ball gets wet.

If the soil is insufficiently warm, mulch the plant with a few inches of compost. If it’s still cool, wait a few weeks. If you have cutworms, place a cardboard collar around the transplants.

Peppers need regular watering but not too much—most pepper problems are caused by overwatering or poor soil drainage. In most cases, a drip-irrigation system is preferable to overhead watering. In extremely hot climates, overhead sprinklers are sometimes used to cool down plants and soil. See Appendix A for more information on watering, drip-irrigation, and weeding.

The large hybrid bell peppers, New Mexico chilies, and jalapeños usually need staking (above) or the branches break from the weight of the fruit and plants can blow over in the wind.

Peppers don’t need their own garden. Here, ‘Golden Bells’ were planted in a little garden (above) in the same type of soil and on the same drip lines with zucchinis, popcorn, and tomatoes. A few months later (below) they had all filled in and were doing well.

In warm climates, applying a thick organic mulch can increase your pepper yield as well as save you time, effort, and water. Mulching also helps keep weeds under control. See page 28 for information on maintaining and mulching peppers in cooler climates.

Preventing Pests and Diseases

In most climates, peppers have far fewer pests and diseases than most vegetables. The key to most pepper problems is prevention, which is my emphasis here. If you do develop pest and disease problems, there is information in Appendix B on how to identify and control them.

One of the keys to preventing pepper problems is to understand the role of beneficial organisms in our gardens. Peppers do not grow in a vacuum, and we need to consider the entire ecosystem in which they are grown. This concept was made most clear to me the year the State of California mandated that my county be sprayed with malathion for control of the dreaded medfly (Mediterranean fruit fly). Within a few weeks after the helicopters sprayed our neighborhood, most of my vegetables were infested with insects and my peppers were no exception—they were so covered by aphids and whiteflies that the leaves drooped. I ended up taking out all my vegetables because they were so overrun with pests. Most years I seldom if ever see an aphid or whitefly on my peppers, much less have a problem. That year, nature was completely out of balance, because malathion is a broad-spectrum pesticide and consequently killed off the beneficial insects as well as the pests. Unfortunately, most beneficial insects have a much slower recovery rate than pest insects. Sadly, it was two years before the insect population returned to normal.