Читать книгу Missing - Every Year, Thousands of People Vanish Without Trace. Here are the True Stories Behind Some of These Mysteries - Rose Rouse - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

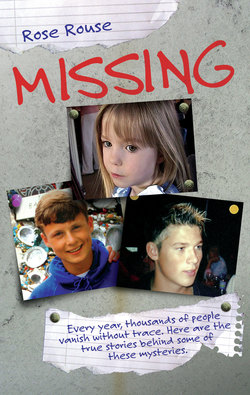

I Miss My Sweet, Gorgeous Son

ОглавлениеJo Gibson Clark has had more heartbreak in the last two and a half years than any mother should experience, ever. Her gorgeous, charming, adventurous 19-year-old son, Eddie, went missing on 24 October 2004, in Cambodia. It should never have happened. On that date, Eddie was supposed to be at lectures as part of his joint honours degree in International Management and Asian-Pacific Studies at Leeds University.

Jo lives in Hove with her second husband, Tony Clark, and had two other sons, Elliott, 28, and Max, 18, by her first husband, Mike Gibson. Mike was also Eddie’s father and, although the parents split up when Eddie was just 11, they remained on good terms and Mike would often pop over for Sunday lunch. Jo drove Eddie up to Leeds on 15 September 2004. ‘He seemed keen to get on with his degree,’ she says. ‘He’d done a gap year with friends and they’d travelled to Australia, Thailand, Burma, Laos and Cambodia, so Eddie seemed absolutely ready to study and said he valued his education. He appeared to be very keen to start his new course. I was really happy for him.’

Ever entrepreneurial, Eddie had managed at the last minute to talk his way into a university room right next to one of his old friends from Brighton, Josh. That really pleased him. And his mother. The room wasn’t great but it wasn’t too bad either. ‘It smelt like a hospital in there,’ says Jo. ‘And it had bars on the window, which I thought he’d find difficult to cope with, but we went out and bought rugs, throws, candles and lamps to give it a homely feel and he seemed fine. Josh, Eddie, Max and I all went out for a nice meal together and I kissed him goodbye, convinced that he was starting an exciting new phase of his life.’ That was to be Jo’s last face-to-face encounter with her lovely son.

Eddie had blond, spiky hair and was six feet tall. Not surprisingly, he was always a firm favourite with the girls and he was smart too, with A grades in his A-levels. Definitely a bit of a star. He seemed to have led a charmed existence and Jo fully expected him to continue in the same manner. However, he did have a streak of dare devil in him even when he was a young boy and perhaps that willingness to take risks caught up with him. ‘How could I have possibly guessed that I’d never see him again?’ she asks, still in a state of confusion about how and why he disappeared.

For the first week at university, Eddie seemed fine. He phoned both his parents regularly and told them all the news about fresher’s week and Leeds. They didn’t suspect anything was wrong at all. ‘He’d signed up to do sky-diving, which he loved,’ she says, ‘and joined a football team. He seemed contented and to be settling in.’

But the true picture wasn’t as clear as that. In fact, Eddie seemed to be hiding some deep confusion. At some point between 15 September and 4 October 2004, Eddie changed his mind about his course and being at university. He decided it wasn’t for him. But he kept this information to himself. He might have been afraid that his parents would feel he was letting them down, and he was never good at facing that kind of situation. He didn’t even tell his old friend Josh. ‘He wasn’t naturally secretive,’ says Jo, ‘but he didn’t like having to explain his actions or confronting things. He’d rather approach tricky situations like this sideways rather than head on. Also, once he’d decided on a course of action, he was single minded in his determination to carry it out. He’d always been like that.’

In fact, there were a couple of clues that all was not well just before 4 October, the date that Eddie took a flight to Bangkok via Dubai with £3,000 from his bank account. On Friday, 1 October, at 10.30pm, which was quite late for him to ring, he called his mother. ‘He said, “I just want to hear your voice, Mum,” which was very unusual,’ she said. ‘I was touched but I was also surprised.’

Then on Sunday, 3 October, she had another call from him. ‘He said, “Mum, I’m really unhappy about my course and I’m not sure what to do.” I told him not to panic, that it would all sort itself out. I knew he was sensible and I wasn’t really worried. I thought he’d work it out,’ she says. He rang again later that day and said that he was changing his course from International Management to Business and that he’d talked to the right professor about this. He added that his battery on his mobile was low, which meant he wouldn’t be phoning home for a few days.

At this point, Jo wasn’t concerned because she thought he’d organised his change of course and that he was OK. ‘He was always so capable,’ she says. ‘I expected him to be OK. What I didn’t realise was that he’d already made up his mind to go back to Cambodia.’ Eddie was evidently in some turmoil about this decision. Much later, Jo actually discovered that he had bought a ticket to Bangkok the day before he called and travelled down to Heathrow. At the last minute, he’d changed his mind again and gone back to Leeds. This was when he’d talked to his mother, but hadn’t told her the full extent of his worries and plans. He was probably thinking that he was creating disappointment for his family and couldn’t face that.

On the Monday, Eddie bought another ticket and this time he got on the plane. Later, his parents found out that he’d stayed in Bangkok for a couple of days before crossing the border into Cambodia on 9 October. ‘Now I wonder if he was setting up a bank account,’ says Jo. ‘He was sensible with money. I can’t imagine him walking around with £3,000 in his pocket. That’s one of the things we’re still trying to investigate – what exactly Eddie did with his money.’

Eddie had been captivated by Cambodia during his gap year. With a group of school friends, he went to Australia, then to Thailand, Laos and Burma, but it was Cambodia that captured his heart. The combination of their tragic history – 1.7 million Cambodians were killed by the terrible Khmer Rouge between 1975 and 1979 in the infamous ‘killing fields’ – the poverty and the kindness of the people he met had a profound effect on him.

‘He met people who had no relatives because they’d all been killed by the Pol Pot regime and who had no money, yet Eddie thought they seemed much happier than people in the West,’ says Jo. ‘That made him question our value system here. He came back and threw out his Armani and Boss clothes. He didn’t see the need for them any more. He walked around in T-shirts, flip flops and shorts just like he’d worn over there. He didn’t like the greed he saw in the West.’

Finally, he seemed to have made the decision that it was more important for him to experience more of this kind of non-materialistic existence in Cambodia than to take his university degree course. He had a return flight booked for 1 November so he was planning to be away at least a month. Not that his family realised that any of this was happening. They thought that Eddie was happily ensconced in his hall of residence in Leeds. Jo did think it was a little strange that Eddie missed his brother Max’s birthday on that first Wednesday. He sent a card and a present but he didn’t phone. She tried to ring his mobile but there was no answer. She rang Josh and asked if he’d seen Eddie and he said he thought he’d seen him somewhere but Jo wasn’t reassured.

By the end of the week, Jo was in a terrible state. ‘I rang the university and asked them to break into his room,’ she says. ‘I was imagining that Eddie was lying dead in a pool of blood. Finally, they did get in and Josh reported that everything was still there except for a little satchel, a black holdall, his passport and money. Then, I knew that he’d probably gone abroad. I was incredibly shocked and worried.’

She rang the police, who were reluctant to do anything because Eddie was 18 and therefore free to make his own decisions. Then she phoned Missing People, who advised her to phone the Foreign Office to check if he’d left the country. It turned out that Eddie had mentioned to a couple of friends in Hove that he wanted to go back to the Far East, but none of them had taken him seriously.

Jo also phoned around the hospitals in Leeds, checking to see if Eddie was lying there injured. By 15 October, the family knew that Eddie had crossed the border into Cambodia. She turned all her attention back to the police, trying to get them to find out more information. But they weren’t prepared to do anything. Eddie had made the decision to go and that was that as far as they were concerned. ‘Mike wasn’t as worried as me at this stage,’ she says. ‘He thought it was just Eddie doing his own thing.’

Finally, on 20 October, Jo got an email from Eddie in Phnom Penh. ‘I felt the happiest I’ve ever been,’ she says. ‘I was so excited, so relieved and so incredulous all at once. I’d been emailing him three or four times a day, and the rest of the family and friends had been too, so he must have had at least a hundred emails. He apologised for going off without telling us and explained that university just wasn’t for him. He said he was coming back on 1 November and told me not to worry. He also said I was the best mum in the world and he was looking forward to seeing us all again. Then he made it clear that he wasn’t going to open his emails again because he wanted “to clear my head and decide what to do with the next three years of my life”.’

Eddie gave her the impression that this was something he had to go through on his own. Of course, Jo was overjoyed to hear from her son, but she also wanted to let him know what she’d been going through. She emailed him back. ‘Oh my God, promise you will never do that again. You have no idea how worried I’ve been and what thoughts have been going through my mind. I can’t wait to see you. I’m not angry with you and it doesn’t matter about university. You are bright and everything will be fine.’ Jo is not sure whether Eddie ever read it.

She received one more email four days later. ‘He said he was definitely coming home on 1 November,’ she says, ‘and he was ready to come because he’d seen enough of the poverty and deprivation over there.’ It was enough to reassure her and convince her. Jo was looking forward to having her son home in her arms again. Both parents were determined to be there at Heathrow when Eddie got off that flight.

They drove up together from Sussex. Jo was so excited about seeing and holding her son after so much anxiety over his safety. At 7.15pm, travellers started to come through from the flight from Bangkok. Jo and Mike were right in the front of the exit doors ready to give him a huge welcome. But ten minutes later there were only a few stragglers with backpacks left. And none of them was their son. The doors shut and these two parents had to face the nightmare reality that Eddie was not there. He had not come back.

‘I felt torn apart,’ says Jo. ‘My emotions just went into overdrive. Waves of shock and terror ripped through me.’ She ran over to the British Airways desk and asked them to check whether Eddie had boarded the flight in Bangkok. She was allowed to know, but only because she worked as a member of British Airways ground staff and was able to show them her security pass. They confirmed that Eddie hadn’t got on the plane. Jo had thought her living hell was about to end – tragically, it was just about to start.

Jo later confessed that, on the way to the airport, she’d had a faint suspicion that Eddie wouldn’t arrive, while Mike was still convinced that Eddie would be back in his own time. At home, Jo couldn’t hold back the pain and anger any longer. She wrote Eddie an email that was incandescent with rage. It read, ‘I can’t believe the pain you are putting us through. We were so looking forward to seeing you. I can’t believe you would be so selfish. You don’t know what it is like to be a parent and go through this. Make contact with us. Let me know you’re OK.’

Naturally, Jo was absolutely desperate to hear from her missing son. She wanted to tell him everything she was feeling and how hurt she was. She wanted to communicate with him and hear what was happening to her boy. But in fact, she never heard another word from Eddie. The next day, feeling terribly guilty, she sent him another email apologising. Meanwhile, Mike was still confident that Eddie would come home when he was ready. ‘Remember,’ he would say, ‘Ed hates fuss and confrontation, and having to explain his actions. He’ll be home in his own time.’

To keep her mind occupied, Jo busied herself with activities connected to finding Eddie. She phoned prisons in Thailand to see if he could be there – although she is quick to point out that she always warned Eddie about people planting drugs on him and that he was never interested in drugs. She also phoned the Buddhist centres in Cambodia. ‘I thought Eddie might have decided to clear his head there,’ she explains. ‘I even found a professor who specialised in Buddhism who was going there. He said he’d check them out for me but on his return he told me that it was very unlikely that Eddie was in that sort of centre. Not many Westerners can take that sort of regime, which includes cleaning rotas and being up at 4am, plus they also only speak Cambodian.

Jo also sent out a chain global email saying she was looking for her son and asking if anyone had seen him. She got emails back but no real news. Eddie had kept detailed dairies of his gap year, so Jo read them now, looking for names of hotels in Cambodia and then emailing them to see if Eddie had stayed there recently. She was incredibly industrious. But she didn’t have any luck.

Christmas 2004 was approaching and they were all convinced that Eddie wouldn’t miss it. But, horribly, there was no word from him. Now his father and eldest brother Elliott decided to take action and flew out to Cambodia to try to find him. ‘It was a dreadful Christmas,’ says Jo. ‘We had my mother over and she’s eighty-seven. We hadn’t told her about Eddie because we didn’t want to worry her. But now I had to tell her. She took it better than I thought she was going to, but I suppose she lived through two wars when people went missing regularly. Telling her somehow made it official. It made me feel in total despair.’

Unbelievably, Mike and Elliott arrived in Phnom Penh and the tsunami happened on the same day. All the police officials with whom they had wanted to find and discuss Eddie’s disappearance had been diverted to Vietnam and Thailand. However, they did manage to put ‘missing’ posters up everywhere.

‘From the diaries, I could see Eddie had had a relationship with a girl in Bangkok. Mike and Elliott managed to find her but they discovered he hadn’t gone back to visit her this time,’ she says. ‘But she started to help us too.’ They talked to bar owners and went down to beaches where travellers hang out. Cambodian girls would say they’d seen him, but these sightings all proved to be untrue. Yet Mike and Elliott came back still positive, still thinking he was there somewhere, they just hadn’t found him yet.

Unable to stay at home when the others had been in the country where Eddie had gone missing, three weeks later, Jo and Tony flew to Phnom Penh. They met up with the British embassy’s vice consul who explained that Westerners would often get picked up by ‘taxi’ girls, who would totally look after them in return for being financially supported. ‘He said Westerners often occupied this unreal, bubble world, which was lovely, very peaceful and cheap. Then there were the local drugs like yabba, an opium derivative, which would keep them permanently high. Lots of Westerners apparently end up living out here for ten years just to escape life at home,’ says Jo. Presumably, the embassy official was suggesting that Eddie could have made that choice too.

However, Jo couldn’t see Eddie getting into drugs. He liked being in control too much, plus he was really into his health. ‘Unlike my other boys, he was always shopping for fruit and vegetables,’ she said. ‘He really cared what he put in his mouth.’ Jo had an aim on her trip and it was to get on TV and in the newspapers over there. ‘I wanted as many people as possible to be aware that Eddie was missing,’ she says.

Unlike her son, Jo hated Cambodia. ‘It is the worst place I’ve ever been to,’ she says. ‘I saw all the pretty girls there and the beaches, but underneath there is such a basic need to survive that people will do anything for money. There is also a feeling of immorality that maybe came from the Pol Pot era. It feels as though people will do anything, however ruthless, to survive. We went to one of the backpacker’s hangouts and it was horrific, filthy and full of drug addicts – it was vile. We looked to see if Eddie’s name was on the register, but it wasn’t. I was so shocked by these places. Parents would never let their children go there if they knew what they were like.’

Jo managed to get a lot of coverage on TV, radio and in the newspapers. Expats offered help, Cambodians also came forth and offered information, but Jo was only too aware that the latter were often just interested in the cash being offered. One Cambodian man said to her, disturbingly, ‘You realise that people get killed here for fifty dollars and the killers simply bury the bodies.’ The horror of the possibilities in a country with such a corrupt underbelly hit her, but Jo refused to give up. ‘I was crying, I felt so sick,’ she says. ‘We also tried police stations, which was another horrible experience. The police there have gold teeth and crisp, green uniforms, but they don’t inspire any confidence. Basically, they won’t do anything without being paid. Everyone wants to be paid. It’s very demoralising.’

She did find a man called George who did sincerely offer to help. He was an American lawyer who put posters up and contacted hotels to see if Eddie had been there. There was also Gareth, a lovely Welsh man who Jo happened to ask for directions when she was walking along the beach. He recognised her voice because he’d heard her do a radio interview there about Eddie. ‘Are you Eddie Gibson’s mum?’ he said immediately.

‘I was so excited that he knew who I was, it made me feel hopeful. He has turned into a friend and helped out a lot,’ she says.

But mostly she was approached by shifty characters who were obviously after money. Which made her search even more distressing. There was one man who was Israeli and, she says, looked like Colonel Gaddafi. He promised he’d find Eddie, but she didn’t even consider taking him on. ‘I was still going to bars and half expecting Eddie to be sitting there,’ she says.

Leaving Cambodia without any concrete news about Eddie was extremely tough for Jo. ‘I was so sad,’ she says, fighting back the tears. ‘I felt as though I was leaving my Eddie there. That was so difficult emotionally.’

Back home, she kept getting emails. Most were from Cambodians claiming to have news of her son, but they were obviously lying. They were all insisting, of course, that they needed money to help. Then Jo received an email from a Korean girl called Constance who was living in Phnom Penh. She was a friend of a Cambodian girl called Ami, who had apparently been having a relationship in October with Eddie. At last, this was the possibility of a real breakthrough. Jo allowed herself to become a little hopeful of finding out the truth.

And this piece of information turned out to be real. It transpired that Eddie had been staying with Ami from 9–24 October. The lovely Welshman, George, was duly dispatched to find Constance and to try to locate Ami through her. He did. Eddie had, it turned out, met Ami during his gap year at a club in Phnom Penh called the Heart of Darkness (ominously named after the Joseph Conrad novel that inspired the film Apocalypse Now). Eddie was obviously keen on her because he went back to see her on his second visit. Ami and Eddie hung out together, she stayed in his room at different hotels, he visited the small wooden shack where she lived with her parents and they seemed to have had a sweet relationship.

Over these couple of weeks, Ami’s father died and, because she had no money, Eddie paid for the funeral. There was even a video of the funeral, which Jo eventually got hold of. ‘For me, finding Ami was the biggest breakthrough,’ she says. ‘Eddie is on that video and he doesn’t look like he’s on drugs or anything. He looks like Eddie. He has his arms round Ami from time to time and they look as though they were close. Eddie was obviously trying to help her out. At her father’s wake, they look very happy together.’

Not long afterwards, Mike went back to Cambodia with Eddie’s godfather. They met up with Ami and asked her questions about what Eddie had done during that time. She confirmed that she had been with him until 24 October. The other significant person was a young man called Trip. Eddie had befriended him on his first visit. ‘Trip hangs around the border next to Thailand,’ says Jo, ‘and he organised for Eddie and his friends to go to Angkor Wat, which is when they became friends. Trip is one of the individuals Eddie had talked about when he came back to England. Mike even eventually got the police to interview him, but he did not have any information.’

Meanwhile, Ami told them that Eddie had said he was going to Thailand with two friends after he left her on 24 October. He promised her that he would come back to see her in three weeks time. Ami also told Eddie’s father that they had been thinking of living together and even having babies. ‘He would say that,’ says Jo, ‘because he didn’t want to be unkind. He had a string of different women around the world, so I don’t take that too seriously.’ The wooden shack where she lived had not had any improvements made to it. Ami wasn’t living the high life. Of course, during this time, the possibility that Eddie had been murdered remained.

In November 2005, Mike went out again and this time met the Prime Minister of Cambodia. Jo and he had the idea that the best course of action would be to get some British detectives out there to do an investigation. They were disillusioned with the Cambodian police and thought the British would do a better job, but Cambodian protocol dictated that they had to have a Prime Ministerial invitation. They were successful. ‘Mike also met up with a private detective from Australia who said he could help us,’ she says. ‘We ended up taking him on and he’s been on the case now for two years. But he hasn’t come up with anything useful and we have paid him a lot of money.’

Neither Mike nor Jo went out to Cambodia in 2006. They left the enquiries to the private detective. And finally in the June of that year, a team of British detectives did go out to look for Eddie. ‘This was great news for us,’ she says. ‘We had to work so hard to enable it to actually take place. In fact, it was the first time ever that British police had been allowed in the country. That felt like a major coup.’

The British detectives were there for two weeks and Mike and Jo were sure they would find out what had happened. ‘They were a crime investigation unit,’ she says, ‘so they knew what they were doing and they did interview a lot of people.

‘But in the end, frustratingly, they concluded that they didn’t know what had happened and they didn’t come up with any new information.’

Jo was disappointed but decided to take no news as good news. Maybe Eddie’s still there, she thought to herself, and too scared to come home. Even as a small child, Eddie had been adventurous. He was in and out of cupboards at home.

‘That was the beginning of his personality,’ says Jo. ‘He also always used to make people laugh. Eddie was always the centre of attention without quite meaning to be.’ As Eddie grew up, he was also fearless. He was always willing to take risks. At school, he was a character, intelligent but often in trouble. ‘Like when he was a teenager, he went on a school trip to France and the teachers couldn’t find him or his friend. He was eventually found in the girls’ changing room. Not that the girls minded. He was a mischievous boy but everyone loved him.’

However, Eddie went on to get ten GCSEs, mostly As and Bs, then three As at A-level in Business Studies, IT and Communication Studies. ‘He worked really hard for them,’ says Jo. ‘All his friends would be on the beach but he’d shut himself in his room so he deserved his results. When he wanted to be, he was utterly focused. In this case, he wanted to beat Elliott’s results. Elliott got two Bs and a C, so Eddie had to do better. He was competitive with himself. He was very happy to have succeeded but he didn’t brag; that wasn’t his style.’

His gap year was a huge success. Eight of them, girls and boys, all old school friends, went off travelling together. Eddie was always a bit of a wheeler and dealer so he made money for his trip by selling whatever he could on eBay. He’d go to car boot sales, he’d buy his friends’ unwanted possessions and he’d make money from them. When Eddie wanted to do something, he would make sure it actually happened.

One of Jo’s favourite memories is of joining Eddie in Australia earlier in 2004. ‘He was there as part of his gap year and it was his birthday. He was 19 so Tony and I went over to visit him there, ‘she explains. ‘Mike and Max had already been. Eddie had bought a Cadillac while he was there and they’d travelled up the east coast to Cairns and stayed quite a few weeks in Surfer’s Paradise on the way. He loved Australia but he was really looking forward to some real travelling in the Far East.’

In fact, Jo had some of the happiest days of her life with him there. ‘I took Eddie to the hairdressers. He wanted a few blond highlights put in. He was so handsome and charming, and all the stylists clustered around him. I felt immensely proud,’ she says. Afterwards, they lunched beside Sydney Opera House and talked and talked. ‘He was my son but he was also my friend,’ she says movingly. ‘He held my hand in his enormous hands. It was so sweet.’

Jo also took him to hospital because he’d broken his wrist up on the Gold Coast and it needed more attention. ‘Eddie told me that he’d broken his wrist playing football on the beach,’ she says. ‘But five months after he’d gone missing, I found out from his friends that he’d actually fallen twenty-five feet from an apartment onto the beach. They were having a party and the balcony was very low, which explains why the break was so bad. I’m sure Ed didn’t tell me these details because he didn’t want me to worry.’

After that, he and his friends went off to Bangkok, Laos, Burma, Vietnam and Cambodia. As his family was to discover, it was Cambodia that really affected him. ‘The people there have nothing,’ he would say when he got back, ‘but they are happier than us with everything.’ It was an attraction that cost him and his family very, very dearly.

In January 2007, Jo and Mike went back to Cambodia once again. ‘We’d just had another Christmas without Eddie, ‘she says, ‘and I really felt it would be good to get on TV and radio out there again and appeal to everyone as a mother who was being tormented by the disappearance of her son. I wanted to implore anyone who knows anything to come forward. I want to stop living in limbo and discover what happened to Eddie. Even if he’s dead, it’s better than living like this.’

His parents offered US $20,000 for information. ‘We decided to put a figure on the money,’ she says, ‘so it’s more real to people. That’s a lot of money in a country where the average policeman earns just US $300 a year. We desperately hope it will tempt people to tell the truth. Someone must know something.’

Jo’s biggest fear is that someone killed Eddie for his money. He had £3,000 when he left the UK, but what did he do with it? Jo really wants to establish how he was carrying his money and if he had traveller’s cheques or had opened a bank account out there. This information will help them form an opinion at least about whether Eddie was simply murdered for his cash.

‘I don’t know how discreet he was with it. He was always very careful with money,’ she says, ‘but life is cheap in Cambodia and, as a result of so much violence and death in their culture, people are hardened to killing.’

At the moment, Jo and Mike cannot move forward. They still do not know what happened to their son. It seemed that he was planning to leave Cambodia and go to Thailand, perhaps to catch his flight home. However, there is no evidence that he ever left Cambodia. They’ve been up to the border between Thailand and Cambodia and seen how lawless it is. But they still don’t know if Eddie made it there.

Jo keeps his room at home unchanged. It’s full of souvenirs from his trips. She treasures them for his sake and reads his diaries to keep herself feeling close to him. They have great support from friends and family. His brothers raise money by doing sponsored runs and providing the cash to fund the private detective. Everyone is doing their bit. But all of this doesn’t alter the unpalatable reality. They still don’t know what has happened to Eddie. ‘Sometimes, I look at the email from him that says he’s going to clear his head and decide what he’s going to do for the next three years, ‘she says, ‘and wonder whether he will just walk back in the door this October.’

In the meantime, Jo, Mike and their family are not giving up. They’re intending to go back to Cambodia again this year and put more pressure on the Cambodian police. There are more questions to be asked. The police haven’t spoken to the passengers who sat next to Eddie on the way out there – did he say anything to them? Jo is not about to stop searching. And she never will.