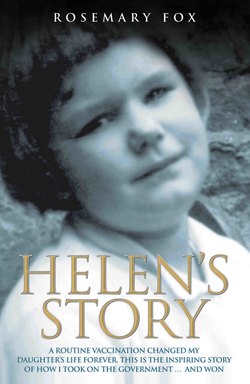

Читать книгу Helen's Story - Rosemary Fox - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Association

ОглавлениеHelen was the only vaccine-damaged child I knew at the time, and I wondered how I might track down any of the children mentioned in the published reports, in order to meet their parents and hear their stories.

At around that time, a party was arranged by the manager of the playgroup for disabled children which Helen attended and, while sitting watching the children enjoying themselves, I saw another young girl whose behaviour seemed to be very similar to Helen’s. She, too, looked completely normal, but in a roomful of quiet children she was running around in circles just like Helen. Her name was Joanne Lennon and when I asked her mother, Rene, what had been the cause of her disability, I was amazed when she said ‘polio vaccination’. It then occurred to me that I had details of at least two cases as a starting point in my search for others.

The easiest way to contact other affected families was to have a story published in the press, but knowing that this might not be easy, because of the fear of the public media being branded irresponsible, I thought our local newspaper might be a good place to start, if, indeed, they were prepared to write the story.

Celia Hall, now the medical editor of the Telegraph, was the Health Correspondent for the Birmingham Post at the time and I phoned her to discuss the possibility of an article about the two girls. She agreed to meet Joanne’s mother and myself and, after a long talk about the background to the girls’ condition, agreed to cover the story. At the time, I think she, too, was conscious of the criticism it might attract from the medical profession but, as the tattered yellow memo slip in my file which she brought with her shows, she had done her homework. Celia had first checked to see if there were any expert references to reactions to vaccination, and had brought with her what was listed as ‘Dr Millar’s Patent Preventative Reading List’. In this was listed a series of references to conditions linked to the aftermath of various vaccines, all of which confirmed that vaccine damage was a reality and something which would bear discussion. Again, it was clear that details of damage following vaccination had been available for many years and what was surprising was that the public had never been informed. Her detailed article about Helen and Joanne appeared in the Birmingham Post on 26 June 1973.

Under a large headline reading, WHOSE BURDEN? there were photographs of Helen and Joanne and details of the reactions which had caused their damage. The article stated:

‘It said on Helen Fox’s clinic card Protect YOUR child by vaccination … For Helen the irony of that sound advice is bitter.’

It went on to describe the development of Helen’s convulsions, the numerous visits to doctors and specialists. The article told the story of her life up to 1973 when it became clear that, despite suggestions from some doctors that she might not live beyond the age of 8; and despite suggestions from a Health Visitor to ‘send her away as she will ruin your life and that of your other children’, Helen had settled down and was attending a special school in Stratford upon Avon.

‘She is now obedient but she does like running away,’ stated the article. ‘Her father is now building the garden wall a foot higher to stop her getting out because when she runs, she’s off!’

‘“Joanne was an adorable baby,”’ the article said, quoting her mother Rene.

At 13 months, Joanne had a polio vaccination and three days later was critically ill, had a violent convulsion and was rushed into hospital. She stayed there for six weeks suffering constant convulsions and Rene was told her baby would be a degenerate. When the convulsions stopped Joanne slept for hours and one day when Rene went to see her she thought Joanne looked so normal sleeping that she was filled with hope until Joanne opened her eyes and was, ‘just a babbling child, not seeing or hearing.’ She was eight when the article was written and her mother described her then as ‘a pretty little girl. Most of her problems can be solved with a kiss.’

Referring to an article in the British Medical Journal which was arguing for a compensation scheme for vaccine damage, Celia Hall added that we now wanted to form a society so that from a position of strength we could put pressure on the Government for a compensation scheme.

Helen was then eleven years old. Seeing the story in print brought home to me again the tragedy which had resulted from my consent to vaccination without any knowledge of risk. It also strengthened my resolve to do something positive about it.

Rene and I had agreed that I would deal with the secretarial side and the publicity, while she would provide backup and moral support and together we would set up meetings with other parents.

The Guardian followed the Birmingham Post’s lead with another detailed article about the girls and my proposed campaign for them and, as a result of these two articles, I received 28 letters from parents with a similar story to tell. A total of 28 cases was, I thought then, quite a considerable number, but little did I know of the hundreds of letters which were to pour in in the coming months.

It was during the interview for the Birmingham Post that a name for the fledgling campaign group was decided on – The Association of Parents of Vaccine Damaged Children. It is undeniably a long title that doesn’t lend itself to an interesting abbreviation, and there were criticisms of it from time to time from the media. The families involved, however, came to know it as ‘The Association’, which continues to be its informal title to the present day.

Reading through the first batch of letters was incredibly upsetting. We were used to coping with our own tragedies but, thinking they were fairly unique, it was a shock to find how many other families were suffering as well. Most wrote about convulsions; some had children who were partially paralysed. I was aware that the letters were mostly from local, very literate families and it was obvious that I needed a popular newspaper to contact parents nationally. At that point, Jean Carr of the Sunday Mirror phoned to say that she was interested in the story and wanted details for an article. The article appeared one Sunday in August 1973.

A week went by and then, on the following Monday morning, the telephone rang very early. It was Jean Carr asking me to go down to the Mirror offices to help to answer the hundreds of phone calls and enquiries which had poured into the Mirror since my article had appeared. Parents from all over the country were phoning to tell their stories and nearly all said they thought they were the only ones to whom this had happened. Listening to what they had to say, and later reading their letters, I needed no further convincing that what I was about to embark on was fully justified. Far from being a ‘one in a million chance’, as the Department of Health liked to call the possibility of damage from vaccination, what I and many other parents had thought of as something which had unfortunately happened to our child alone had been a far more common occurrence. By the end of 1973, I had received around 280 letters from parents. Nearly all said ‘I thought I was the only one’ and ‘I have been a voice crying in the wilderness because no one would listen when I said vaccination caused the damage’.

The vaccinations mentioned covered all of those in routine use at the time – measles, smallpox, oral and injected polio vaccine, rubella (given at school), BCG, and the triple of diphtheria, tetanus and whooping cough. Three out of every four letters indicated the cause as being the triple, and most blamed the whooping cough part of the triple, which was the reason why whooping cough vaccination became the most talked about during the campaign.

At that stage, with a list of 280 families anxious to take part in the Association’s campaign, I selected a number of replies from parents living in Warwickshire and asked them if they would like to come to a meeting in Birmingham to talk about starting a campaign for our children. About 12 people agreed and one was able to arrange the use of a small church hall.

I recall it was a pleasant summer evening and I picked up Rene on the way to Birmingham and we talked excitedly about what looked like a promising start to our fight for our daughters.

David had to stay at home to look after the rest of the family as did Joanne’s father. While it was very easy for families with ‘normal’ children to arrange babysitters or leave their children with strangers, this was never the case for those of us with children who needed special care. Not only would we be worried about whether they would be looked after properly but it was not easy to find people prepared to look after them. It is only in recent years that a greater awareness of disability has created a greater willingness on the part of the public generally to accept disabled people as being no different from anyone else. In the seventies, however, this was not the case so mothers and fathers had to split the babysitting between them.

Having arrived at the hall and introduced ourselves to the other parents, we spent some time telling each other our stories and I explained how I wanted to go about setting up a campaign group. We talked about how difficult it was to get doctors and professionals to accept that vaccine damage was real. The most common statement from parents writing to us was, ‘I was a voice crying in the wilderness’ i.e. no one would take what they were saying seriously. So the first thing we had to do was to collect and publish reports from experts who knew what we were talking about. We then had to go to the Government and tell them that if some European countries – such as Denmark, Germany, Hungary, Norway and Japan – were taking responsibility for the damage created and paying compensation to the sufferers, there should be a similar scheme for our children.

Our aims were set out as:

1. To establish the reality of vaccine damage

2. To seek some kind of insurance of the scheme in order to protect the rights of those who were damaged

As a novice group our aims were not clearly worded and were later to be corrected by Barbara Castle, who pointed out that insurance was for future events and would not cover for any past events. What we were really saying was that we wanted to prove that our children were vaccine damaged and we wanted the State to make special provision for them.

It was decided that parents would be asked to contribute £2 each to fund the work that would be necessary but it was also decided that we would not be a very formal group with detailed rules and regulations. It was agreed that I would act as Honorary Secretary, calling on others in the group for help as necessary, and also that we did not want to get involved in the minutiae of rules about meetings, quorums, members’ voting rights and all the other aspects of formal constitutions. As a campaign group, we would not qualify for charity status and, since all our efforts would be concentrated on the work involved, we would not have any care/welfare/advice role which might divert our efforts.

Our one concession to formality was the decision to have account details audited annually to ensure there could never be any suggestion that collected funds were incorrectly handled, and one parent whose daughter had reacted to a measles vaccination, but had fortunately recovered, offered her help as Treasurer. All monies went to her and were audited and we stuck strictly to our auditor’s advice that we should never seek or accept large sums from external organisations or raise more than the amount needed to cover postage, phone calls and travel expenses.

The decision taken not to have a formal constitution proved to be very important years later when some parents formed a splinter group and wanted to take over the running of the Association and the campaign, expecting to see a constitution with rules which would enable them to do so. Stories abound of groups in which a few members become dissatisfied, criticise the founders and go over their heads to the other members seeking their votes for a change in the constitution which would allow new leaders to be appointed. Where this succeeds, it must be a very bitter blow for anyone who has worked hard to get a project off the ground and running successfully, only to be dismissed at the whim of a few dissatisfied people. Although such a possibility never occurred to me when making the original informal arrangements for our group, I was very glad much later on that our arrangements made it impossible.

Following our Birmingham meeting – and with nearly 300 reports from parents all over the country – I wrote to ask if any parent would like to act as an Area Secretary to keep in touch with parents in their region. Part of their job would be to pass on information quickly and to encourage the parents in their area to keep in touch with their Members of Parliament. I thought that this arrangement would work much better than an elected committee governed by rules and regulations. 13 parents from various parts of the country agreed. This arrangement worked well until the first breakthrough in 1979 when the Vaccine Damage Payment Act was passed.

Scotland already had its own campaign figurehead in Helen Scott, whose son had been damaged by smallpox vaccination and she had been fighting for him. Her case load was to increase greatly when news of our campaign spread and Scottish parents wrote with their stories. Helen continued to lead the campaign with parents in Scotland and was a valuable source of information and help over the years. In Northern Ireland, the parent of another victim of smallpox vaccination provided a contact for parents there which meant that the campaign now covered the whole of the UK.

These informal arrangements not only proved to be highly effective but also removed the possibility of any friction arising from arguments or differences of opinion among members of an elected committee. It was to be 25 years later that such a committee was formed and almost immediately led to arguments and upsets.