Читать книгу Helen's Story - Rosemary Fox - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

A Life Less Ordinary

ОглавлениеHelen is my second daughter and was born on 8 February l962. At the time, my husband David and I lived in Devon with our two-and-a-half-year-old daughter Suzanne in the bungalow which was to be our home for another few years. When Suzanne was born in 1960, my mother had come from Ireland on a visit to see her and decided to stay on for a while and to help me look after the baby. After a month or so we agreed that she should stay with us on a more permanent basis. At 64 she was tired of her farming life and wanted a change. Since I missed my job and wanted to go back to work, the arrangement was ideal for both of us. She stayed on until December 1961, which enabled me to continue my job as Secretary to the Directors of an engineering company until shortly before Helen’s birth. The company made turbine blades for aircraft and the Directors had been involved with jet engines since their first work with Frank Whittle, the famous inventor of the jet engine. As a secretary, my work was fascinating and I had contacts with all kinds of interesting people in the aircraft industry.

When my mother left in 1961, I missed her help but she had been starting to worry about her own home and the farm, which was being looked after by my brother and she wanted to take over the reins again. From then on until her death in 1977, she came back for occasional visits and we sometimes went over to see her.

David was an engineer working for a national heating engineering company. His work was interesting and well-paid, but when I stopped working we really felt the difference to our joint income.

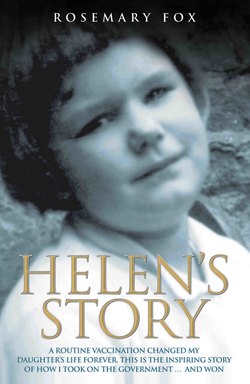

Helen was a chubby, happy baby who progressed normally until she was seven months old, when she had her first polio vaccination. She slept well, fed well and was altogether a pleasure to look after. We spent our days joining in local playgroups, visiting the pleasant beaches that were close by, or simply going out shopping, with Helen in her pram and Suzanne sitting on a pram seat.

The Health Visitor who had previously visited Suzanne came to see Helen about her immunisations when she was 3 months old, advising the triple (whooping cough, diphtheria and anti-tetanus) which she was given. We were advised to give her the polio vaccination, which she had in September 1962 at 7 months old.

If my mother had still been with me things might have been very different. The previous year, on hearing that we had been advised that Suzanne should be vaccinated against measles – a new vaccine according to the Health Visitor – my mother had said, ‘What on earth do you want to do that for? Children get measles and, if they are properly looked after, they recover.’

In private she had said to me, ‘For heaven’s sake don’t do it.’

I hadn’t argued with her.

Thank God I had listened to her as, years later, I was to discover that the measles vaccine in question was ‘on trial’ at the time and was later withdrawn following reports of deaths in vaccinated children.

When it came to the polio vaccination, however, Mother wasn’t there to advise.

At that time, the vaccine used was an injected Salk-type vaccine, a similar type to the American vaccine manufactured in this country by Burroughs Wellcome, both of which did not have the risk of leading to the disease, unlike the oral polio vaccine.

The day after the vaccination in September 1962, when I went to pick Helen up from her morning nap I found her pale and comatose. She had vomited over herself and her cot and, as I walked around with her in my arms, waiting for her to wake up, I was worried about what might have caused her sickness. I decided that if she took her midday bottle it would mean she was not too ill, and when she fed normally I stopped worrying. However, within a day, the vomiting became projectile, travelling at least 4 feet across the room from where she was sitting, which was so unusual that I phoned the doctor.

‘Leave it for a few days,’ he said,‘but if she continues to vomit like that, call me again.’

When he called a day or so later, he diagnosed pyloric stenosis, describing it as a condition in which the pyloric valve flips back the milk rather than allowing it to pass to the stomach. A simple operation would be needed, the doctor said, but first he prescribed some medicine which might cure the condition.

I had been told that my sister-in-law had suffered a similar condition when she had been about six weeks old and had had a minor operation which cured the vomiting, so although I wasn’t too happy about a surgical procedure, I wasn’t too worried about the vomiting, which stopped after the prescribed medicine had been finished.

Our bungalow was part of a development surrounded by other bungalows in which lived other young mothers and babies. Four or five of us got together each morning to form a playtime group for the children and to provide a coffee session for the grown-ups. Helen was eight months old and, with her sister Suzanne, joined in happily with the children’s games. Watching her crawling around and playing, I noticed that she would occasionally stop still for a second or two and then burp. The pyloric valve, I thought, was not quite right and I made a note to keep watching her so that I could check with the doctor to make sure she did not need that operation after all.

Then, one day, when she was 12 months old and was standing holding on to the window ledge, she turned and fell flat on the floor. I just thought she had lost her balance but a friend with whom I was having coffee at the time said very seriously,‘There is something wrong with her – go and see the doctor.’

Looking into Helen’s face as I picked her up, I was reminded of a girl who had been a classmate of mine when I was about 12 years old, who used to stop and stare during lessons and was said by the teacher to be having fits. Strangely enough, that girl used to position herself next to me to hold my hand when she felt a seizure coming on, and now my heart stopped, as I realised that Helen was probably going through the same thing – she must have been suffering from minor epileptic attacks since she first became ill at eight months.

The doctor was concerned and helpful when I went to see him to explain my fears. He remembered my visit after the vaccination but, like a lot of other doctors at the time who had never heard of vaccine damage, he had not regarded it as significant. He arranged blood tests and stool tests, but all were clear. He then started coming to the house occasionally hoping to see Helen during a seizure but, of course, it was always five or ten minutes after he left that the seizure started.

By the age of 18 months, the seizures had become major convulsions from which Helen has never recovered, and it was then that the round of hospital visits to consultants and specialists began; doctors of all kinds tried to discover the underlying cause of her condition and then determine what, if anything, could be done to cure it.

Having a sick child was bad enough, but constant visits to clinics and specialists added greatly to the distress. Every visit held the promise of a diagnosis or of a treatment which would cure the condition, but they just became causes of extra upset. Waiting around to see the specialist, undressing and weighing a fractious child because nurses wanted details for their records, all in a crowded waiting room full of other upset children and weary mothers was a nightmare. Finally getting to the specialist’s room and sitting while he asked umpteen questions about the medical history, the medication, the child’s behaviour, and then ultimately being given little more than a further appointment in a few months’ time was immensely disappointing. Yet back we went time after time for further appointments hoping for some breakthrough.

These visits to specialists continue to the present day, although they are not so focused now on finding a cure, but are still necessary to assess and treat the various conditions which are created by Helen’s disability. Her anti-convulsant drugs need constant monitoring; her allergic reactions to various substances need classifying and treating; and the fractures she has suffered in falls during epileptic seizures have required surgery. She is very fortunate nowadays in that she is under the care of a concerned specialist who sees her regularly to check her medication and refers her for any special treatment she needs.

We went from specialist to specialist trying to find a cure until, in the end, we realised there was no cure and that coping with the condition as positively and practically as possible was the best way forward. Yet we learned something from each specialist: Dr Haas, at the Children’s Hospital in Exeter, was the first to see Helen at 18 months old, and told me pyloric stenosis couldn’t happen at 7 months. The pyloric vomiting was, he said, a sign of brain disturbance. This revived all the concerns I had about Helen’s sudden illness after the vaccination and the damage it caused, which I mentioned to every doctor and specialist I saw in the following years. All disputed that such a thing was possible:‘Vaccination is protection,’ they said, and could not possibly be a source of damage.

The visit to Dr Haas coincided with the date on which I was due to give birth to my third baby but I was so anxious to get expert help for Helen that I went ahead with the meeting. I think I did warn him that I might have to leave in a hurry, and he was very considerate! As it turned out, the baby arrived three days later on 3rd August and was given my mother’s name, Rosanna.

Helen next saw Dr Ounsted at the Park Hospital in Headington, Oxford, when she was five years old. He was carrying out a study into ‘naturally occurring convulsions in childhood’ which was part of the reason he was interested in her case. The hospital provided accommodation for visiting mothers with young families and I stayed there with Helen and my youngest daughter, Rosanna, for five weeks while the doctors carried out their tests. The possibility of brain surgery was discussed, but having been told by Dr Ounsted that Helen had the same chance of being cured, of suffering further damage or simply of there being no change, we dismissed the idea.

Helen was then referred to Dr Brian Bower, an Oxford specialist and, for the first time, there was a breakthrough in what up until then had been the mystery of Helen’s change from a happy, healthy baby to a brain-damaged one. Dr Bower focused on my concerns about Helen’s vaccination and subsequent illness. He was, I discovered, studying reactions to whooping cough vaccination and had published a paper, along with Dr PM Jeavons, in the British Medical Journal in 1960 about children admitted to Great Ormond Street suffering severe illnesses within 24 hours of inoculation.

At the time of Helen’s injection and reaction, I knew very little about vaccination. I had previously worked as secretary to the directors of an engineering company and had heard the Technical Director complain from time to time about the injections he had before travelling abroad, some of which made him ill. I knew also that there had been publicity about the Salk polio vaccine in America and rumours of damage and deaths following its use, but when I asked my Health Visitor about this, she said not to worry, ‘you know what the Americans are like’. In my ignorance, I agreed with her, feeling that Americans were probably not as carefully organised and cautious as the authorities in the UK were.

Again, it was years later when I discovered that at the time of Helen’s vaccination in 1962 the Department of Health had decided to stop using Salk Vaccine and were promoting a new Sabin live virus vaccine instead. Clearly it hadn’t been available at Helen’s clinic at the time and she had been given the Salk: what difference, if any, it might have made if the Sabin had been available we will never know but even that vaccine is known to give polio to a small percentage of children.

There was an interesting debate in the House of Lords in December 1982 about the rights of vaccine-damaged children which told some of the story of Salk vaccine. Lord Hailsham, then Lord Chancellor, speaking on behalf of the Conservative government and arguing against any special provision for those who were damaged, said,

‘I will tell a very short anecdote if I may to illustrate why I say that.’[that vaccination is not a public policy]. He went on to say that 30 years previously he had been placed in the position of having to decide ‘whether to import a thing called the Salk vaccine … The argument for importing it was that there was only a very small quantity available of a British vaccine which was safe and therefore if I did not import it there would be a large number of children who would not have any vaccine at all … The argument against importing it was that there had recently occurred a thing called the Cutter incident as a result of which in the United States … a number of children had not only caught polio from the vaccine but had died from it or had suffered permanent injury.’

Having sought advice from the Medical Research Council about whether, in view of the Cutter incident, it was safer for a child to be vaccinated or not to be vaccinated, he was told that it is much safer to run the risk of vaccination than not to run the risk.

‘Therefore I challenge the view which has been put forward – and accepted I think with too great a facility by nearly every speaker in this debate – that the mere fact that the Government are on the side of vaccination gives the disabled child who suffers from the vaccination a better chance than the child who suffers and who has not been vaccinated and as he is only 3 years old has no responsibility at all who has caught the disease and who suffers permanent disability from it.’

Dr Bower agreed to look into Helen’s case and collected her vaccination and medical records. He then gave us his opinion that the polio vaccination at seven months old and the illness which followed were the probable causes of Helen’s condition. I was concerned at first that ‘probable’ was not a very definite diagnosis, but Dr Bower explained that it meant that it was the nearest thing to certainty in cases like vaccine damage which could only be assessed after the event.

Driving home after the consultation with Dr Bower, my husband and I first talked of our relief at finally knowing for certain what had caused Helen’s brain damage.

‘Just imagine,’ I said, ‘after all these years wondering about Helen’s vaccination, we now know we were right to blame it for Helen’s condition’

We both went on to wonder if there was anything we could do about it and David said ‘We have let seven years pass and I wonder if something could have been done earlier to help her.’

For years, I had wondered whether anything I had done had harmed my daughter, or whether simple things like the food she ate, or even silly things like the material in her clothes and shoes, could be causing reactions. It is surprising how one’s mind can come up with all sorts of ridiculous explanations for a condition which has no name. Now I had a specialist supporting my theory, and my suspicions about the vaccination had been fully justified; I was not mad to consider the vaccination as being the cause of Helen’s disabilities, and I could at last ‘put a name’ to her condition. Only then could I begin to get on with accepting her condition and making the best possible provision for my daughter’s future security and happiness.

My initial relief soon turned to anger at the realisation that her vaccination had changed her from a healthy to a disabled child. I had taken a healthy child to a clinic on the advice of a Health Visitor acting for a Health Authority carrying out the wishes of a Government Health Department, having been told that it was to protect Helen’s health but without any warning of any possible risk. What I had not been told and did not fully realise was that Helen was just a statistic in the immunisation process – one child among thousands who had to be vaccinated to meet the Health Authorities’ programme of wiping out disease and preventing its return, the success of which depended on getting the largest possible number of children vaccinated. It seemed to me that, somewhere along the line, the need to protect the rights of any child who might be injured in this way had been overlooked, so I decided for Helen’s sake and for the sake of any others in her position to start an investigation, which turned into a campaign.

Today, Helen is 43 years old. For the past ten years she has been happily settled in a small residential home with a high level of caring and qualified staff. She has constant family contact and home visits. The decision to place her in the home was another heartbreak for Helen’s father and me, but knowing that we would most probably die before her, we had to make sure that she was happily settled in another ‘home’ while we were still alive and able to satisfy ourselves that she was happy and well cared for. Some parents cannot cope with arranging residential care for their children and hope that brothers and sisters will eventually take over the care. There are others like us who feel that care is best placed in the hands of a statutory authority which ensures long-term continuity.

Helen is a happy, affectionate young woman and, although she does not speak, she understands what is said to her. She is one of five residents in her care home and has a settled routine. They take her shopping, walking and on interesting day trips. An aromatherapist goes to see her once a week and there are outings to sensory rooms which she finds relaxing.

Twice a week, she goes to a special day centre run by social services. The brilliant staff organise many activities such as swimming and riding. Recently they told me they were taking her ice skating – which was really surprising! They explained that they took the wheelchairs on the rink and the carers skated around with them. I am told Helen loves it, as do the others.

Without all her very caring helpers, she would not be able to do any of these things and I am constantly reminded of how much we, her parents, and Helen herself, owe to the wonderful people who are prepared to take on the care of disabled people.

She continues to take anti-convulsant medication which has reduced the number of her severe seizures, but it is clear that both the medication and the seizures have had a disastrous effect on any chance she may have had to develop normally. She has a lovely face with a completely normal expression and it is difficult sometimes for others to understand that she is brain damaged. She cannot look after herself; left alone in a house full of food, she would not know how to feed herself or ask for help.

The greatest worry to all parents of the disabled is what will happen to their children after they have died. At least we know that Helen is happy in her home, that she has caring staff to look after and love her and that she has two sisters who will make sure she continues to be well and happy.