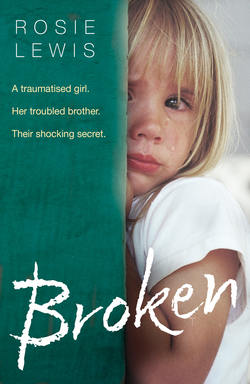

Читать книгу Broken: A traumatised girl. Her troubled brother. Their shocking secret. - Rosie Lewis - Страница 11

Chapter Five

ОглавлениеThe next day, Friday 2 January, began peacefully enough. I woke at just after 5 a.m. to the gentle sound of glass bottles clinking against doorsteps as the milkman made his deliveries. Hoping for half an hour to myself, I got up immediately and went downstairs. Mungo greeted me, tail wagging, in the hall and followed me as I switched on the computer and went into the kitchen. I made myself a coffee and fussed him while I waited for it to boot up.

With the steaming drink at my side and Mungo at my feet, I sat at my desk to type up the previous day’s notes into my foster-carer diary. Foster carers are expected to keep detailed daily notes for each child they care for, recording such things as times and dates when babysitters are used, incidents of difficult behaviour and potential triggers, periods away from home, illnesses, medication, doctor’s visits, meetings, any disagreements that may have occurred – either with the child, their birth family during contact or with professionals – damage, theft, or involvements with police, and then email them at the end of each week to the child’s social worker for uploading onto social services’ computer system.

Record keeping is an important part of a foster carer’s role, not only to protect against possible allegations (emailing the diaries provides the foster carer with proof that nothing has been added to the record or altered at a later stage) but also to provide a detailed history for the child in the future, should they choose to read their file when they reach adulthood. When I’d finished, I set the table for breakfast so that it was ready for the children as soon as they came down.

Megan was first to rise, if you discounted Bobbi’s six wake-ups during the night. As Joan had mentioned, she talked a lot in her sleep, and every hour or so she called out to me. The first time I went in she complained that she didn’t like the dark, so I put a couple of plug-in night lights in the room. I went back to bed and she called me ten minutes later to tell me that the teddies I’d arranged around her bed were too starey. I collected them up and put them in the hall but she still woke an hour or so later.

I went in to her each time and reassured her she was safe, but no sooner had I gone back to sleep than she was calling out again. The noise woke Megan several times as well, who was finding it difficult to sleep anyway because of a stomach ache. I gave her some Calpol and a hot-water bottle to ease her cramps, but she still tossed and turned, groaning whenever Bobbi called out. Tucked away in the top bunk, Archie somehow slept through the entire racket.

‘Morning, my angel,’ I whispered, lifting Megan into my arms. ‘How’s your tummy this morning?’

She frowned, her disturbed night all forgotten. She cuddled close as I carried her downstairs, her head resting on my shoulder. I could feel the hard plastic of her hearing aid pressing into my skin and felt a swell of pride at her resourcefulness; over the last week or so she had taken to fitting the aid herself each morning. Sometimes she forgot to switch it on, but negotiating it into her ear was a feat in itself.

I told her how clever she was and she beamed – her reaction evidence that she had managed to switch it on. I gave her some milk and we cuddled up on the sofa, the soft fur of Mungo’s head warming my feet. I buried my head in Megan’s hair, relishing the opportunity to hug her while she was in a sleepy state of early morning calmness, and so unusually still. It was still only half past six and I was hoping to spend at least half an hour of one-to-one time with her, as I had always tried to do with Emily and Jamie when they were younger. Megan, it seemed, had other ideas.

‘No, sweetheart, let them rest,’ I said, when she slipped off the sofa and tried to pull me upstairs. ‘Let’s make the most of some Mummy and Meggie time.’ She didn’t look entirely convinced on the merits of just having me to play with, but she acquiesced. We read Felicity Wishes, one of her favourite books of the moment, and then we read it again.

Just as I was about to embark on a third reading, there was a thump overhead. Mungo’s ears pricked up. Megan was off the sofa and at the bottom of the stairs within a few seconds. As I followed her up the sound of arguing reached me, followed by another loud clunk.

Megan stopped short at Archie and Bobbi’s bedroom door. At first I thought she was respecting the house rules and was about to congratulate her for being so vigilant, when I caught a glimpse of the room. All of the clothes that I had folded neatly away in the drawers were scattered all over the floor. The wardrobe doors hung open, the clothes inside dangling precariously from their hangers.

Lidless felt-tip pens were strewn here and there, two upended water bottles leaking over them and creating a rainbow effect on the beige carpet. And just visible at the edge of all the mess, I could see a few food wrappers sticking out from under the bed. Megan and I exchanged mutually shocked glances.

I picked my way through the rubbish. Megan followed. She stood next to me, hands on her hips. ‘What’s happened here?’ I asked, trying to keep my tone neutral. Between the ages of eighteen months and seven years, children are convinced that they are responsible for everything that happens to them. This so-called magical thinking, a natural phase of development, leaves children convinced that they are responsible for their own plight when they come into care. Instead of placing any fault with their parents, they assume that they are not worthy of being loved. I was worried that if I made a big deal of it, I could add to the toxic shame the siblings probably already felt. Besides, in my experience, most everyday upsets resolved themselves quickly if ignored.

Bobbi, still in her nightdress and pull-up nappy, was sitting in amongst the mess with a few pens clasped in one of her hands, the rabbit I had given her in the other. She looked blank, as if I hadn’t even spoken. I took another step towards her, noticing as I did that her picture had been torn from the wall, a few fragments of jagged paper left behind. The drawing, I presumed, lay somewhere beneath her. I wondered who had taken it down, and why. I looked at Archie, who was already dressed and standing by the window. He was staring into the garden, his face angled away.

‘We’ll clear this up later,’ I said firmly. By messing up the room, there was every chance that Bobbi had been unconsciously re-creating her home environment. Home might have been an awful place to be, but it was familiar and probably strangely comforting. Having noticed Archie’s fastidiousness, I had already decided that Bobbi was responsible for the mess. ‘Now, who’s ready for breakfast?’ I asked. Archie turned to me in surprise.

Bobbi jumped up. ‘Me! I am! I want cornflakes and toast and yoghurt and chocolate.’

‘I don’t know about chocolate!’ I said, laughing. ‘Right, we must all try to keep quiet as we go down. Emily and Jamie want a lie-in today. Bobbi, let’s get you sorted.’ The smell from her soiled nappy was overpowering, even from where I was standing. I wanted to shower her down before we went downstairs.

‘No, I want breakfast now.’ Bobbi’s tone was flat but insistent.

‘Yep, soon. Let’s go the bathroom and get you cleaned up first.’

She eyed me defiantly. Sensing a sharpening of the atmosphere, I turned to Megan. ‘Meggie, would you like to go and choose yourself something to wear?’ She nodded enthusiastically and trotted off to her room. I craned my head around the door and called out: ‘Don’t forget, it’s winter!’ She loved getting herself dressed but more often than not she’d appear wearing a swimming costume or a pair of hot pants, even on the iciest of days. ‘Right,’ I held out my hand. ‘Come on then, pickle, let’s sort you out.’

‘Nooooo!’ Bobbi yelled, her cheeks turning puce. ‘I want food!’

‘Tell you what. I’ll go to the bathroom and wait for you. If you come within ten seconds I’ll give you a sticker. Archie, you go downstairs whenever you’re ready. Emily found The Chamber of Secrets when she came in last night. She’s left it on the table for you.’

Archie tiptoed around the mess to the landing, still looking a bit taken aback. Clearly he was expecting a different reaction to the one I’d given.

Bobbi scooted after him but I caught her around the middle and lifted her up, careful not to touch her full nappy. ‘Gotcha,’ I said playfully, trying to avoid her kicks while not breathing too deeply; her nappy really did smell bad. She dropped the rabbit and lashed out, catching my cheek in the exact spot that had only just scabbed over. My skin prickled and stung. ‘Let’s try and stay calm,’ I said, my own adrenaline kicking in.

‘Nooooo!’ she screeched again, pummelling my face and neck with closed fists as I carried her to the bathroom and knelt in front of her. ‘Kind hands, Bobbi,’ I said, my voice sounding strained as I fended her hands away. She clawed at my arm by way of reply, her nails digging at the bare skin on my wrist until tiny spots of blood appeared.

‘Bobbi, you’re safe, sweetie. No one’s going to hurt you. Let’s just calm down and get you cleaned up.’

She was screaming so hysterically that I wasn’t even sure she heard me. Even if she had been able to process what I was saying, part of me knew that ‘calm down’ probably didn’t mean much to a child who had grown up amid chaos. ‘Be kind’ was a meaningless instruction to someone who had, in all likelihood, been mistreated since birth. I knew that. But with adrenaline surging through my veins, it was difficult to think of anything else to say but ‘calm down’.

I took a few deep breaths and realised that I was staring at her, probably with a horrified expression on my face. I forced myself to look away. ‘I’m going to cut you!’ she screamed, still trying to run at me. ‘I’m going to cut your cheeks and twist them off your ugly face.’

Another blast of adrenaline shot through my veins. I wondered what on earth she had experienced to come out with things like that. I fended her off, my mind flashing to the pictures in her room. I took a calming breath, grateful that at least Megan probably couldn’t hear any of what was going on.

‘Bobbi, I’m going to hold you close and help you to feel better.’ Being out of control was terrifying for a child. As I reached out I knew she would fight against me, but I also knew that she needed to understand that I was the one in charge. The sooner she realised that I would keep her safe, the calmer she would feel.

Enfolding her flailing arms with one of my own, I turned her around and pulled her onto my lap so that her back was pressed against my middle. Almost immediately I felt a warm trickle of liquid on my thigh as the contents of her nappy seeped through her nightdress and over my jeans. Simultaneously, the overwhelming stench of excrement hit my nostrils. I held my breath, trying not to gag.

She thrashed around on my lap, arching her back and trying to launch another assault. As gently as I could – I was anxious not to mark her skin – I held onto her wrists and cuddled her close. ‘There, it’s alright, I will keep you safe.’ I tried to force my mind away from the growing brown stain on my jeans. Eventually her screams turned to sobs and her struggles subsided, her body pliable enough for me to gently rock her to and fro.

When she fell silent I stayed where I was. If I moved too early she was likely to remember her anger and start all over again. Besides that, her stiffened features were softening and, with a sting of pity, I realised that she’d probably never been babied before.

In the early days of placement, when children are railing against the sudden changes that have been foisted upon them, it’s sometimes difficult to return their aggression with affection. One of the best pieces of advice I’ve been given is to ‘fake it until you make it’. It’s near impossible to love a stranger, especially an abusive one, but when you go through the motions of caring for someone, genuine affection usually grows. As the adult, it was up to me to forge a loving attachment with Bobbi.

After a few minutes I eased her gently to a standing position and rose to my feet. Wordlessly, I knelt on the side of the bath and sprayed down my jeans using the hand-held shower head, aware of her hiccoughing sobs behind me. I worked hard to extinguish the look of disgust from my face as I got a nappy bag out of the cupboard and lifted her into the bath. Despite the low soothing noises I was making, she reeled away when I reached for her nappy, her fingers clasping the waistband so tightly that her knuckles were turning white. I felt a slow rolling sensation in my stomach.

I thought back to one of the courses I’d recently attended, when our tutor told us to interpret any difficult behaviour as an expression of fear. I knew that bedwetting and soiling wasn’t unusual in victims of sexual abuse – the smell of urine and faeces an unconscious attempt to make themselves less appealing to their abuser – but the fact was, lots of children Bobbi’s age still wet the bed. Soiling was more unusual, but perhaps she had been frightened to venture out to an unfamiliar toilet on her own.

‘Do you like bubbles, Bobbi?’ I asked gently, reaching for Megan’s pot of bubbles on the windowsill. I blew a few bubbles into the air above her head. The effect was instantaneous. Her face lit up and then she reached out and took the pot from me. Engrossed in her efforts to blow more bubbles, she was distracted enough for me to remove her nappy and shower her down.

Megan was waiting outside the door when I opened it. I felt a surge of guilt but she looked up at me with an expectant smile and I realised that she probably hadn’t heard a thing. Most of the time I felt sad about Megan’s hearing difficulties and would gladly have shared my own with her if I possibly could have, but, I have to admit, on that morning it was more of a blessing than a curse.

‘Here we are, guys,’ I said twenty minutes later, after washing and changing into a clean pair of jeans. I placed a sand timer on the table. ‘I have a challenge for you. We’re going to see if we can chew every mouthful of our cereal for thirty seconds. The time starts when I turn the timer over, okay?’

Archie, who had been reading, looked up from his book. ‘Yay!’ Megan exclaimed, grinning at the others. ‘I can. I can do it!’ I wasn’t sure whether Bobbi had even heard me. She started on her Weetabix without even looking at the timer, scooping another huge spoonful into her mouth a few seconds later. My heart sank. I had introduced the ‘game’ to all of them, but Bobbi was the one most in need of it.

From the wrappings over their bedroom floor, I suspected that both Archie and Bobbi had already eaten something. I hadn’t noticed anything missing from my own cupboards so assumed that they must still be working their way through food that had been hoarded at Joan’s. I planned to tackle them about it in a day or two – I didn’t want them to keep food in their rooms – but I wanted them to feel a bit more secure before I removed that particular safety blanket.

‘Bobbi,’ I said, ‘you can turn the timer over first.’ She stopped chewing and looked at me, her cheeks pouched with food. Archie dug into his cereal and held the spoon in front of his mouth, staring at the timer with focussed intensity.

‘What?’ Bobbi asked thickly, dropping her spoon into the bowl.

‘The sand timer. Turn it over and chew your next mouthful until the sand runs out.’ Her eyes flickered with interest as she reached out, turned the timer over and plonked it down again. All three of them scooped up their cereal and began chewing.

Bobbi’s mouth worked, her eyes flicking competitively between her brother and Megan. ‘Done it, Mummy!’ Megan shrieked, as the last grains of sand filtered through the timer. Archie grinned then flipped the timer over again. Watching the timer intently, they tucked in again.

I sat with them and joined in, trying and failing to make each mouthful of my porridge last the full thirty seconds.

‘That was a really nice breakfast, Rosie. You’re the best cook.’

I smiled. ‘Thank you, Archie.’

‘I want more!’ Bobbi shouted, adding ‘please’ when I gave her a look. Another helping and two glasses of milk later, she was still ‘starving’. I told her she’d had enough, repeating my mantra about there always being enough food for her at Rosie’s house. A flurry of protests followed but I shook my head, turned the television on and started clearing the table. Megan and Archie went and sat on the rug and watched cartoons, Mungo rolling around on his back between them. Ecstatic with all the attention, his tail thumped noisily on the floor as they tickled his middle.

Bobbi grabbed my wrist and shook it. ‘Rosie, I need more, I do, Rosie, I do!’

‘You can have some fruit soon, and they’ll be lots more food for lunch and dinner. They’ll be plenty of food today, tomorrow, the next day and every day that you’re here, I promise.’

Her mouth drooped at the edges as if she didn’t believe a word of it but she sloped off her chair and stamped across the room. Mungo sprang to his feet before she reached the rug and trotted off to hide under the coffee table.

After clearing away the breakfast things I decided to try and tackle Bobbi’s knotted hair. She hadn’t allowed me to wash it in the bath the previous night and it was matted at the ends where she’d slept on it slightly damp. Without saying a word, I planted two doll’s styling heads on the rug, one in front of each of the girls, along with a hairbrush for each of them and some styling accessories.

Bobbi swooped, scooping everything up for herself. ‘There are some for you and some for Megan,’ I said, returning half to Megan, who was watching Bobbi peevishly.

‘My dolly doesn’t want these anyway,’ Bobbi said sulkily, sweeping her half back to Megan. ‘She has a bad headache.’

‘Does she now?’ I went to the first-aid cupboard and pulled out some old, out-of-date bandages and plasters. ‘Perhaps she needs some of these.’

Bobbi looked thrilled. While Megan covered her doll’s head in hair clips and lipstick, Bobbi covered hers from top to bottom in bandages.

Absorbed by the cartoons and the doll, she didn’t protest when I got to work on her hair. She kept shuffling forward on her bottom though, only stopping when she was about a foot from the television. I hauled her back each time, wondering whether her eyesight was all that it should be. I made a mental note to book an appointment for her at the opticians.

I used a wide-toothed comb on her hair, trying my best not to pull on the tangled ends. It was as I worked my way back towards the nape of her neck that I noticed something unusual – the back of her head was almost entirely flat. My heart lurched. I knew that since the ‘back to sleep’ campaign had been launched to reduce the number of sudden infant deaths, more babies had developed flattened spots on their skull as a result of laying in the same position in their cots or car seats, but Bobbi’s was an extreme example, her scalp devoid of even the merest hint of a curve. I felt a swell of sympathy for the baby she had been, probably left alone for hours, perhaps even days at a time.

When I’d finished I sat at the table on the opposite side of the room and added a note in my daily diary about Bobbi’s flattened scalp to the growing list of worries accumulating beneath her name. The opposite page, the one for her brother, was blank. I wrote ‘Archie’ at the top and drew a line underneath it. There hadn’t been a single incident of difficult or even mildly challenging behaviour from him since he’d arrived.

Even so, I was hoping to speak to Danny Brookes, the children’s social worker soon. I had missed a call from him earlier that day. He’d left a message on my mobile to give his name as my point of contact, but when I’d called back, his own answerphone had kicked in. I fired off a quick email to the fostering team listing my concerns and asked them to forward it onto Danny. What I wanted to say about Archie, I couldn’t exactly put my finger on. My eyes drifted across the room and settled on the children, all sitting cross-legged on the rug. Beneath his thick crop of hair it was difficult to tell whether Archie’s scalp was flat like his sister’s. In fact, beneath his smooth facade it was tricky to work out anything about him. I picked up my notebook and pen again and, beneath Archie’s name, I filled the space with a large question mark.