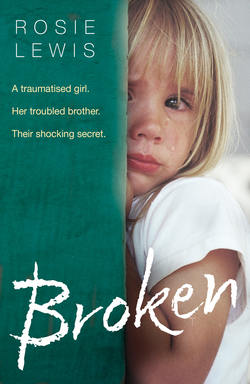

Читать книгу Broken: A traumatised girl. Her troubled brother. Their shocking secret. - Rosie Lewis - Страница 13

Chapter Seven

ОглавлениеSwirling grey clouds hung low in the sky as we drove towards Millfield Primary the next morning. As luck would have it, Megan’s nursery opened fifteen minutes earlier than Archie and Bobbi’s school, so I had been able to drop her off with confidence that I’d make it to Millfield on time.

It was Tuesday 6 January, Bobbi and Archie’s first day back at school after the holidays, and I had woken everyone earlier than usual in anticipation of a major fall-out in getting Bobbi dressed. With careful avoidance of any ‘lifting leg’ instructions, it wasn’t the battle I’d anticipated, as it turned out, and by 8 a.m. everyone had been tucking into their breakfast.

The Jason comment aside, I still knew little about Bobbi’s past – my gentle attempt to encourage her to talk about her fears of punishment batted away last night by a loud screechy song – but there was every reason to suppose that she had been neglected from birth. There were all sorts of likely triggers to her panicked behaviour, some I would only ever be able to guess at.

The smell of sour milk, for example, might set off a hysterical reaction in a child who had lain untended in their cot for hours at a time. I knew that some children in foster care flew off the handle whenever they were cold, the sensation reminding them of the terror they felt as babies, when they had been left to go to sleep without clothes or blankets. For others, loud music caused fear, or shouting, or being smiled at in a certain way; a once-used code from Daddy signalling that it was time to join him upstairs. Trauma triggered behaviour was unpredictable by its very nature; I knew it would take some time to decode.

At a red light I glanced at Bobbi in the rear-view mirror as she made an infernal noise. She looked smart in her uniform and older somehow. I had bought two new sets of uniform for each of the children when I finally made it to the shops yesterday, my mother stepping into the breach so I didn’t have to drag Bobbi around town in her PJs. ‘They’ve been as good as gold,’ Mum announced on my return, a twinkle in her eye. It was often the way with the children I looked after. They seemed to sense the genuine warmth beneath Mum’s firm exterior and responded well to her gentle attentiveness. As an unwanted replacement of their birth mother, it often took longer for me to gain a child’s trust.

‘Maybe you could try being a bit firmer,’ Mum had whispered to me on her way out. My mother holds firmly to the view that punishment and retribution are the most effective means of keeping children on the straight and narrow. Though rarely openly critical, I often got the feeling that she believed my own system of using positive praise, consistency and continuity alongside a careful balance of love and discipline was ridiculously soft.

I rolled my eyes at my brother, Chris, who had popped by to pick Mum up and drop her and Megan to the leisure centre for her swimming lesson. When Bobbi had seen Chris on the doorstep she froze. A few seconds later she had wrapped herself around his shins and was planting rapid kisses on his knee.

Stunned, Chris gave her head a quick pat and threw me a ‘What’s this all about?’ look. I raised my eyes and pulled her gently away. ‘Bobbi, this is my brother but you don’t know him yet. We keep our cuddles for people we know well. Okay, poppet?’ I began to wonder whether she had some sort of attachment disorder. Unscrupulous abusers seemed to have internal radar for vulnerable children like Bobbi. Foster carers are taught to gently dissuade children from being overfamiliar to reduce their risk of sexual exploitation. Bobbi’s random friendliness was yet another concern to add to the list in my diary. I was glad that the siblings’ social worker was due to visit this morning so I could discuss it with him.

‘See, there. That’s where I come out, Rosie,’ Archie told me as we crossed the colourful springy tarmac of the playground. He pointed to an archway at the far end of the brick building in front of us. ‘I’ll be there at half past three, but Bobbi comes out five minutes earlier.’

‘I know, honey. You’ve said.’ The prospect of returning to school seemed to have cracked his facade. He had been fidgety all morning and extra fastidious, straightening every wonky item in his sight. ‘I’ll be here, don’t worry. You enjoy your day.’ He nodded soberly, ruffled the top of his sister’s hair and then picked his way through a crowd of children. Not a single one of them turned to greet or even acknowledge him as he passed. My heart squeezed at the sight. Children in care often struggle to make and maintain friendships, their ability to form relationships compromised by their early experiences.

The Early Years play area was separated from the main playground by a multi-coloured fence. Inside the confines I could see a sand pit, climbing frame and, at the far end, a race track with buggies and cars lined up neatly on the starting line. Part of the playground was shaded by enormous sheets of coloured canvas fixed to tall posts, designed to look like sails on a ship. It was a bright, welcoming space, but one that was failing to work its magic on Bobbi. At my side, she was clinging onto my hand so tightly that I could feel her fingernails digging into my palm.

A young woman with crinkly red hair tied into two long plaits appeared at the Early Years gate, ready to welcome the Reception children in. ‘Hello, nice to meet you, I’m Rosie,’ I said, doing my best to stay upright with Bobbi now clutching at my legs.

The teacher smiled uncertainly. ‘I’m Miss Granville,’ she said, giving Bobbi a wary, almost fearful look. Any help I was hoping for in coaxing Bobbi away from me wasn’t forthcoming, so I went into the classroom with her and gently disentangled myself there.

‘That’s so thoughtful of you,’ the receptionist said when I dropped in my contact information details. ‘I think we have these on file already though. The MASH team were in touch yesterday.’ A motherly-looking woman with a round face and greying hair, she lowered her tone and leaned closer to the glass partition she was sitting behind. ‘Those poor children. It breaks your heart, doesn’t it? I don’t know how you do it.’

Almost every serious case review triggered by the death or serious injury of a child previously identified as being at risk had highlighted a lack of information sharing as a major failing. Multi-Agency Safeguarding Hubs (MASH) were considered the solution; a co-located arrangement of agencies – social services, police, health and education, with close links to probation, youth offending teams and mental health. It was thought that by bringing the agencies together, information sharing, intelligence gathering and networking would vastly improve. The results were noticeable. Now, if police are called to an incident of domestic violence and children are living in the house, their schools are notified before 9 a.m. the following day. Forewarned of the trauma the child may have experienced, teachers are now in a better position to understand distressed or difficult behaviour.

I thanked the receptionist and made to leave, but before I’d reached the door I heard a tapping sound. I turned to see a tall, bespectacled woman with dark hair at the glass. ‘Rosie, sorry,’ she called through a grille in the window. ‘I overheard you introducing yourself. I’m Clare Barnard, the SENCO. Have you got time for a quick word?’