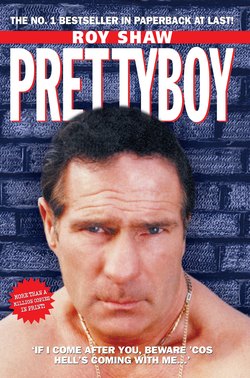

Читать книгу Pretty Boy - If I Come After You Beware 'Cos Hell's Coming With Me - Roy Shaw - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеI ARRIVED AT THE HOME OF ROY SHAW, known as the hardest man in England, on a hot summer day. I looked around at the security protecting his property; closed-circuit cameras monitored my every move. I pressed a small buzzer and waited. Almost immediately, a voice growled over the intercom, ‘Who is it?’

I waved into the security camera and smiled. ‘It’s me, Kate Kray.’

The heavily barred electric gates swept majestically open to let me through. Standing on the driveway was a shiny red Bentley Corniche with a personalised number plate. Next to it was a royal blue Mercedes sports. If that doesn’t just about say it all, then what does?

Although this was the first time I’d been to Roy Shaw’s home, we’d met before on 6 November 1989. The reason the date is so prominent in my mind is because it was the day I married Ronnie Kray, and was the day I was introduced to Ron’s world – the underworld.

Each and every one of the 200 guests dressed in wide-shouldered suits introduced themselves to me in turn. I met them all – hoodlums, bank robbers, enforcers, murderers – but one man who introduced himself was different from the rest, I could feel it the moment I met him. His name was Roy Shaw. I knew instantly he was a formidable man, extremely menacing and very, very dangerous.

We met on the odd occasion at benefit nights laid on by gangsters for gangsters who were doing time. I never got into an in-depth conversation with Roy, it was more a case of a kiss on the cheek, a hug and ‘How’s the Colonel?’

The last time I saw Roy was at my husband’s funeral in March 1995. On that sad day, there were over 50,000 mourners pushing and shoving for a better view of the cortége. Security was tight, and amid the mayhem I noticed Roy Shaw pull up in his Bentley alone. He got out and was dressed in an irridescent electric-blue suit. He straightened his tie and walked towards a wall of security men. As he approached, they stepped back, parting like the Red Sea to let him through. Not one of them challenged him – they daren’t.

Three years on, I arrived at his home to interview him for a book I was in the middle of researching about the toughest men in the country. As he showed me into his lounge on that hot, sunny afternoon, I sat on his sofa and sipped an ice-cold drink and listened as he started to unravel his harrowing life story. The more I listened, I became convinced that Roy Shaw was a cut above the rest in the violent dog-eat-dog world in which he lived.

It was a story that needed to be told, and within a week the contracts were signed and I began to write Roy’s story as he told it.

As each day, and then each week passed, and as the interviews progressed, we slowly peeled away the layers that Roy had built up over the years to protect himself. There was layer upon layer of madness, sadness, indifference, hate and, most of all, anger, that needed to be resolved. Roy went through the gamut of emotions, reliving the highs and lows of his life. He laughed at times, and cried, and was embarrassed by neither.

As we stripped away the protective shell, for the first time in his life Roy bared his soul. There were times when he had difficulty in expressing himself, and understanding why he was such a violent, angry young man.

But that’s just it – there were no reasons. I would like to be able to say he was so violent because of something specific, an underlying problem or a justifiable motive – but I can’t. There is no justification, none whatsoever, for Roy’s violence, and he would agree. He doesn’t blame his childhood or society, and doesn’t try to avoid the truth, because the buck stops with him. Roy laid down his own boundaries for himself and never overstepped the invisible mark, or allowed anyone else to. He has his own priorities which have made him strong, and he has examined his own experiences, good and bad, very carefully, and learned from them.

Every Wednesday and Friday I visited Roy at his luxurious home in Essex. He was always ready and waiting for me with a smile. His greeting was always the same, warm and sincere, but looking into Roy’s face, and particularly deep into his eyes, Roy’s unique character blazed through. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again, his eyes are cold and expressionless, and would look more at home on a great white man-eating shark. They’re small and are closely set above a corrugated nose. Roy appears to stare with an unnerving intensity into a secret world of hostility and hatred.

Everything about Roy spells violence. His shoulders start underneath his chin and spread outwards like a rugged mountain. Touch him and he feels like a rock. He is 15 stone of squat, solid muscle which knots and bulges under his silk shirt when he moves. How he looks, and how he actually is, I found to be a contradiction in itself.

Roy is always a pleasure to be with. He has endearing qualities that, for whatever reason, men of today rarely possess. He is one of the old school, and knows how to treat a lady. He would open doors and step back to let me through, take my coat for me, watch his Ps and Qs in order not to offend me, because it’s not tough or clever to be uncouth. In short, he’s a true gentleman.

The first day I interviewed Roy, he asked me what I liked to drink. From then on, he always added it to his shopping list. Somehow, I always had trouble imagining Roy Shaw pushing a shopping trolley around Marks & Spencers. But he does. Every week. And each time, he’d buy me something special – a cherry or a chocolate cake – which he’d serve on a monogrammed tea plate with the initials ‘RS’ emblazoned on the edge in gold.

I teased him one day by asking him if he’d stayed at the Royal Swallow hotel. He laughed and told me not to be saucy. You only have to scratch the surface to discover that Roy has a dry sense of humour, like the time when he told me he had bought a memory book. When I asked him why he’d bought a memory book, he said that he’d become quite forgetful. He added that it had cost him about £200. I asked to see the book, particularly as it had cost a small fortune, but he shrugged, laughed, and said he’d forgotten where he’d put it. We shared a number of these light-hearted moments while writing his chilling and disturbing story.

Initially, Roy found it difficult talking about himself. He was shy and awkward with me, but after a couple of visits he relaxed and started to open up. He’d protected himself for so long and had never let anyone get close, or see him vulnerable and exposed.

As we were writing this book, he regressed back to childhood and relived every moment, and while talking we stumbled across what I believe to be the trigger for Roy’s deep-rooted anger.

He was badly bullied as a boy, and his father was killed when he was ten. That’s when he had his heart ripped out, leaving him, as some would say, heartless. Roy never dealt with his grief, and from that day on, he pulled up the shutters, battened down the hatches, and cocooned himself in his own world, never allowing himself to be hurt again.

Word on the street soon spread that I was writing Roy’s biography, and everyone had their own story to tell about him, each tale more violent than the last. After describing each violent episode in minute detail, most would whisper, ‘But don’t tell Roy I told you.’

I have written five crime books and I write regularly for a crime magazine, so no amount of violence fazes me. I’ve become hardened to it. It’s true of most cases I’ve researched that there are usually only one or two incidents in a book around which everything else revolves; the rest is descriptive colour, or padding. What makes Roy Shaw’s story different is that no padding was required. In fact, I had to water down instances of sheer brutality because I don’t believe in writing about violence for violence’s sake.

Boys will be boys and men will be men. They all like to poke fires, chase girls and fight. If the truth be told, the majority of men only fight once in a blue moon, if at all. Roy has had a fight almost every day of his life. It comes as naturally to him as breathing.

What is missing from this book, because words do not do them justice, are Roy’s many gestures. On numerous occasions during our conversations, he’d leap up from his seat and demonstrate with clenched fists exactly how he’d whacked someone, or emphasise the venomous thrust when stabbing a victim. But he never did this to brag or show off. It was simply so I could get it exactly right. It was then I saw Roy Shaw come alive when he re-enacted his many murderous acts.

Roy says he is a businessman now and has retired from his profession – violence. The word ‘retirement’ is not applicable to men like Roy; it’s more suited to accountants or lawyers. Gangsters don’t retire – they’re more like legendary cowboys, slowly fading away into the background, because you can never retire from what or who you really are. Roy Shaw is an enforcer and always will be.

At the end of writing this book, I asked Roy if there was anything he wanted to say to the men he’d hurt or the boxers he’d punished in the ring. Perhaps he’d like to take the opportunity for a word or two of regret, explanation or apology? Roy pondered on that thought. I looked into his piercing blue eyes, waiting for some words of wisdom:

‘Mmm .. yeah …’ he nodded. ‘Fuck ’em.’

Kate Kray 2003