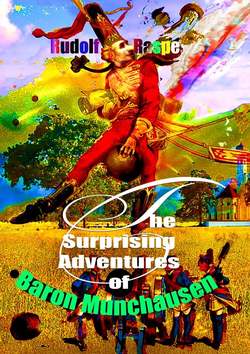

Читать книгу The Surprising Adventures of Baron Munchausen - Rudolf Raspe - Страница 12

TRAVELS OF BARON MUNCHAUSEN

CHAPTER XI

Оглавление_An interesting account of the Baron’s ancestors – A quarrel relative

to the spot where Noah built his ark – The history of the sling, and

its properties – A favourite poet introduced upon no very reputable

occasion – queen Elizabeth’s abstinence – The Baron’s father crosses from

England to Holland upon a marine horse, which he sells for seven hundred

ducats._

You wish (I can see by your countenances) I would inform you how I

became possessed of such a treasure as the sling just mentioned. (Here

facts must be held sacred.) Thus then it was: I am a descendant of the

wife of Uriah, whom we all know David was intimate with; she had several

children by his majesty; they quarrelled once upon a matter of the first

consequence, viz., the spot where Noah’s ark was built, and where it

rested after the flood. A separation consequently ensued. She had often

heard him speak of this sling as his most valuable treasure: this she

stole the night they parted; it was missed before she got out of

his dominions, and she was pursued by no less than six of the king’s

body-guards: however, by using it herself she hit the first of them

(for one was more active in the pursuit than the rest) where David did

Goliath, and killed him on the spot. His companions were so alarmed at

his fall that they retired, and left Uriah’s wife to pursue her journey.

She took with her, I should have informed you before, her favourite son

by this connection, to whom she bequeathed the sling; and thus it has,

without interruption, descended from father to son till it came into my

possession. One of its possessors, my great-great-great-grandfather,

who lived about two hundred and fifty years ago, was upon a visit to

England, and became intimate with a poet who was a great deer-stealer;

I think his name was Shakespeare: he frequently borrowed this sling, and

with it killed so much of Sir Thomas Lucy’s venison, that he narrowly

escaped the fate of my two friends at Gibraltar. Poor Shakespeare was

imprisoned, and my ancestor obtained his freedom in a very singular

manner. Queen Elizabeth was then on the throne, but grown so indolent,

that every trifling matter was a trouble to her; dressing, undressing,

eating, drinking, and some other offices which shall be nameless, made

life a burden to her; all these things he enabled her to do without, or

by a deputy! and what do you think was the only return she could prevail

upon him to accept for such eminent services? setting Shakespeare at

liberty! Such was his affection for that famous writer, that he would

have shortened his own days to add to the number of his friend’s.

I do not hear that any of the queen’s subjects, particularly the

_beef-eaters_, as they are vulgarly called to this day, however they

might be struck with the novelty at the time, much approved of her

living totally without food. She did not survive the practice herself

above seven years and a half.

My father, who was the immediate possessor of this sling before me, told

me the following anecdote: —

He was walking by the sea-shore at Harwich, with this sling in his

pocket; before his paces had covered a mile he was attacked by a fierce

animal called a seahorse, open-mouthed, who ran at him with great fury;

he hesitated a moment, then took out his sling, retreated back about

a hundred yards, stooped for a couple of pebbles, of which there were

plenty under his feet, and slung them both so dexterously at the animal,

that each stone put out an eye, and lodged in the cavities which their

removal had occasioned. He now got upon his back, and drove him into the

sea; for the moment he lost his sight he lost also ferocity, and became

as tame as possible: the sling was placed as a bridle in his mouth; he

was guided with the greatest facility across the ocean, and in less

than three hours they both arrived on the opposite shore, which is about

thirty leagues. The master of the _Three Cups_, at Helvoetsluys, in

Holland, purchased this marine horse, to make an exhibition of, for

seven hundred ducats, which was upwards of three hundred pounds, and the

next day my father paid his passage back in the packet to Harwich.

_ – My father made several curious observations in this passage, which I

will relate hereafter._