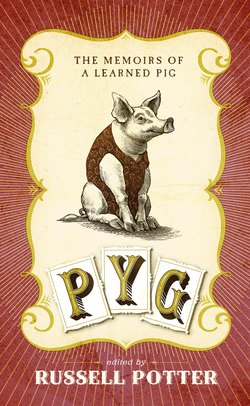

Читать книгу Pyg - Russell Potter - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление5

In the time of the Spanish Inquisition—a History with which I later became Acquainted by these same means—it was customary, before Torturing those accused of Heresy, to show to them the Instruments of their Agony. Many were so overcome by the mere Thought of these implements being used upon them that they at once Confessed to whatever charges the Inquisitor might name, heedless of how by every Word they were thus Damned. Well I knew that Mr Bisset possessed the power of commanding Animals to do his will, but the Means by which he obtained this power were yet a Mystery. The charm of his voice, his pleasant outward demeanour, the food he prepared and set before us, these were surely the chief Rewards that he employed, but what were his Punishments? As these letters and numbers swirled before me, I Resolved, if it were Possible, never to discover what it was that my new Master would do if I did not follow his Commands. And, of course, that was what all the other Animals before me had doubtless done, out of the same Conviction I presently felt, that such a discovery must be as Terrible as the rewards were Pleasant—and that would have been Terrible indeed.

Our routine, which began that Day, never varied. Mr Bisset would point to a card upon which was written a letter or number. He would then Name this card, using several slight indications together: a motion with his eye to the proper card, a pattern of clicks (say, one click and two clucks), and then a third sign, which was a common Word in English. These words did not begin with, or in many cases even include, the letter in Question, but were the sort of words one could easily use in a sentence without drawing any special Attention to them. Words such as ‘Presently’ or ‘Shall’ or ‘Receive’ or ‘Answer’—each of them a cue for a letter, such as J, O, H and N (which are in fact just the letters they represented). He would vary the signs he used, sometimes clicking quietly just under his breath, sometimes employing the words in a Sentence, such as ‘Presently you shall receive your Answer.’ At first the signs were always accompanied by his pointing out the correct letters on each card, after which I would approach the shelf on which they were laid, and pick up each in my Mouth, then drop it on a chalked square on the floor, in the order in which they were Demanded. Once I had perfectly memorised this routine, he would gradually withdraw his other Signs, employing his Eye only. It was remarkable to me that I nearly always Understood his intent, a Phenomenon I can only account for by Supposing that these oft-repeated Routines had established a sort of Intuitive understanding between us.

This whole system, I soon realised, was designed to enable him to carry on with whatever Patter he liked, all the while sending me a clear set of Signals as to the Cards I was to choose. If there was ever any doubt, a brief but imposing glance in the direction of the card wanted, was all that was needed. Which it was unlikely ever to be, for we rehearsed for at least an Hour every day, for the better part of three Months, at the end of which time I had so Completely attuned myself to this Procedure that I could perform it quite without Hesitation or even Thought of any kind. Indeed, whenever Sam chanced to use one of the words that were my signals, I was placed in great Distress, until I could relieve it by fetching the proper letter. By this means, quite by accident, I found that I was able to communicate with Sam, and he with me; he quickly made up a set of smaller cards by hand-writing letters and numbers on squares of pasteboard and, by practice, managed to learn the same Signals my master had Designated for them. Sam’s delight in our Discovery was unbounded, and each Night after Mr Bisset had gone to Rest, he would run me through my Letters.

All this, of course, while it gave me great facility in Spelling any word upon Command, made me no more enlightened about their Sound or Meaning than a Blind man who had learnt his way among the Shelves of a Library; a great Feast of the World’s knowledge was set before me, and yet I could not partake of so much as a single Crumb. My Benefactor at once set to work to correct what he regarded as a most unkind oversight by demonstrating for me the Sounds of each letter and word, and how they came together to make human Speech. He would speak, then spell his meanings, and follow this by spelling out a Word in silence, and have me puzzle out the whole. Well I recall the very first word I learned, and it will come as no surprise to you, my Patient Reader, that this word was S-A-M.

We had to be careful, of course, that I did not vary from my Routine with Mr Bisset, or give him any Idea that I in fact had come to understand the Letters I had previously arranged in ignorance. And yet it did Amuse me to see the sorts of things he had me Spell—given Names were most common among them (John, James, Susan, Alice, Charles and so forth, in great variety), along with words that were meant to answer some simple question, such as Y-E-S, N-O, P-E-R-H-A-P-S and N-E-V-E-R. There could be no more doubt that I was intended for a Show, and a show whose chief Attraction would be to display my seeming-knowledge of the Names of those in the Audience, and my seeming-answers to their Questions.

I must admit that, despite the monotonous nature of these exercises, I took a better Conceit of Myself from this time, imagining the Fame of being such a Notable performer—but then, of course, I thought back to my Prize at the Fair, and how it had been given to my Owner rather than to Me. After all, would it be Man or the Pig who would most surprise the Crowd?

At the same time, with Sam as my tutor, I was embarking on a Course of Study that, though Elementary for any Human child, was Extraordinary for a Pig. Among the books in the Study in Mr Bisset’s house, Sam found a tattered copy of the Fables of Aesop, in the Translation made by Samuel Croxall for the use of the eldest Son of Viscount Sunbury, who had been at the time just Five years of Age. It featured small wood-cuts at the Head of each tale, which were of great help in my Understanding their Sense, and since the Characters within were all represented as Animals, I readily learnt their names. It struck me at once that these so-called Animals were far more Foolish in their nature than any in my Acquaintance, but I soon realised they were but Figures, standing in for the Folly of Man—and, as Men are very foolish, the stories were many, and a great source of Pleasure. I should note here that our usual Practice was for Sam to read the tale aloud, directing me to the New or harder words as he did so, and repeating them until he was sure I had their Sense. By this means, we proceeded far more Quickly than if, as Human children do, I had to manage to Speak before I could Read.

Before long, we could see the signs that Mr Bisset was at last Preparing to set his Show before the Public. By turns, the Cats, the Dogs, Finches, Monkeys, a Hare and, finally a group of Turkeys were all led into the Practice room and marched through their routines at double-time. All had been instructed along similar lines to those I had experienced, with Repetition being the Key, and a series of soft, sharp signals the Prod for them to go through their Paces. The doors were now left open, and I was able to see the Monkeys dance, walk a tight-rope, and play a Barrel-organ, observe the Cats at play upon their Dulcimers and regard the poor Hare beating a drum with a Mallet attached to his Tail. The only group of Animals that had no training as such was the Turkeys, and here I must confess that Mr Bisset hit upon an expedient that did him little Justice, and would have greatly Dimmed the applause had anyone Known of it: he simply placed them in a small wire enclosure, the floor of which was heated to the point where it became uncomfortable to Stand, and the efforts of these poor Birds to avoid scalding their Feet produced the ‘Country Dance’ advertised.

Each day of the week that followed, we were visited by a constant stream of tradesmen with their vans, who delivered specially built cases for the Animals, loads of fresh Straw, canvas dividers and drop-scenes, and stacks of handbills printed on brightly coloured paper. A large wagon, hitherto covered and hidden in a far corner of the Barn, was brought forth, and carefully painted and refurbished. A much-Splattered man with an immense bucket of brushes appeared one morning; although a carriage-painter by trade, he fancied himself a far worthier artist than that, and approached the task at Hand with the gusto of a minor Michelangelo. On each side of the wagon, he painted several oval cartouches depicting scenes of Mr Bisset’s performing Animals; I am somewhat Ashamed to say that I was Delighted to find Myself the subject of the central, and largest of these. ‘THE REMARKABLE SAPIENT PIG,’ he wrote in letters of red edged with gold, and had I the ability not merely to Read but to Speak, I am certain I could have given him the Shock of a Life-time, by quoting those very words back to him. The next day, the word was given out—or the Sense of it, at any rate—that we were to Leave on the Morrow, and once again, I wondered at the capacities of the World, and at the Strange and Singular path my way through it had so far Taken, and appeared very likely to take Again.