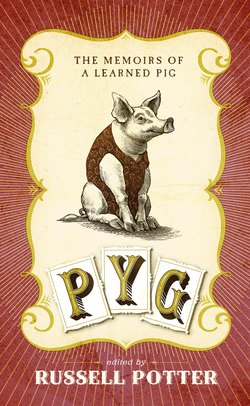

Читать книгу Pyg - Russell Potter - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

When in Rome, do as the Romans. This adage, instilled within human children at a tender age, ensures the extension of a measure of courtesy and understanding to those whose ways are alien to one’s own, and to that degree it is surely a Wise saying. But—and here I speak from painful experience—most who thus employ it scarce understand it. To demand that Humans regard other humans as being like themselves requires little Effort; such sympathy within the species is no more than any other Race of beings expects without a thought. For it is only among humans that other humans seem less than human; among Pigs (or any other Animal, I am sure), such conceits are utterly unknown. Indeed, I believe that throughout the Animal Kingdom, even and especially when one creature attacks and kills another, there is greater Courtesy extended, in each knowing the other to be a living, breathing thing much like itself, than the ordinary Human extends even to his Friends.

I myself was born in or about the year 1781 (as near as I have been able to ascertain), on a farm near Salford, a place not far from the great city of Manchester; so close to it, in fact, that I have since been told it has nearly become a Suburb of that Town. In my own day, its Character was entirely Rural, with a criss-cross of hedgerows and pastures such as would be found in the most remote corner of the country. The whole Region was once known as the Hundred of Salford, which was practically a County in its own Right, and might well have become ‘Salfordshire’ had things worked out differently. My own birthplace was adjacent to the ancient manor of Boothes Hall, just to the North of what is now known as Boothstown, which still preserves something of its original character. My farm lay at the end of Lower New Row, though in my day it had no such name but was called, after its only destination, Lloyd Farm Lane. Mr Francis Lloyd was the owner of this farm and, after the fashion of the local Romans, my owner as well.

Mr Francis Lloyd was a Moderate man in every way: he was Moderately successful as a farmer, Moderate in his politics, Moderate in his treatment of his children, and Moderate in his drinking (which was limited to a Dram before dinner, excepting Sundays). He was not, alas, so Moderate in the treatment of his animals, but that would have been no surprise to his fellow Romans—animals was animals, and one would no more think of extending mercy or kindness to them than one would to a shrub, a stone, or a bit of Tallow. It was not that such creatures had no feelings—surely they did—but only that their feelings were simply not of account. The Squeal of a Piglet was doubtless the expression of some feeling or another, but most of all it was a Noise, a thing to be filtered out of one’s hearing, much as the creak of a floorboard or the sound of wind in the trees. Mr Francis Lloyd raised Pigs to make money, same as he raised Barley or Cows—save that, in the case of the Cows, it was their Milk that was wanted rather than their Blood.

With some animals—horses, mostly—it has been the habit of Men to name, and keep some account of, a creature’s Dam and Sire, if only to make a sort of Mathematics of success; a good Dam might be joined with a famous Sire to make another Champion to win the garland at the next St Leger Stakes. But when it comes to Pigs, men have long felt that there was little sense in naming them, as their only moment of Note was most commonly their being served for Supper, and found more flavourful or delicate than their predecessor—every one of them nameless save by such Ephemeral sobriquets as Loin or Roast. In such a realm of infinite and infinitely replaceable Parts, a row of Dinners one after another, the idea of naming any one such meal appeared as absurd as naming a toenail-clipping, or a Fart. On occasion, when some children from the neighbouring village came to call and wanted to see the pigs, the old Gaffer might call out cheerily to ‘Grunter’ or ‘Stripe’, but as soon as the moment had passed, the name was as forgotten as the dirt at the bottom of a bucket of pig swill. For who did not grunt, or had no stripe? We ourselves might as well have called men ‘Two-legs’ or ‘Hair-head’.

In my own case, it is difficult to say exactly when I acquired my name. For, at the time ‘Toby’ was first bestowed upon me, it was as much a Noise to me as my grunts were to my masters; I had no idea of Language, or any association between such sounds and my own Being. That Gift was later Bestowed upon me by a bright young lad of the name of Samuel Nicholson, Mr Lloyd’s nephew, who was at the time living at his uncle’s Farm. Sam was fond of pigs, and even without the aid of Language, this was instantly discernible to every Inhabitant of the Sty. Our Elders, who had lived long enough to see the previous generation sent to Slaughter, were of course more cautious than myself and the other younger Pigs, who swarmed about the edge of the Sty in competition for a proffered carrot. And, for reasons that to this day I cannot precisely Determine, Sam took a liking to me, and I to Him. Soon, he would Spy me out as soon as he neared the rail, and begin each Visit with some special treat—a slab of Cabbage, some Greens, or a slice of Turnip—intended only for me, after which he would toss a few kitchen scraps to the rest.

In part no doubt due to this favourable Treatment, I quickly grew to be the largest and ruddiest of my Farrow (a word then used to Signify the Pigs born alongside one). Sam was delighted with this, as indeed was Mr Francis Lloyd himself, though for Opposite reasons. For his part, Sam fancied that I would, after the fashion of a household Pet, soon come to his Call and form the sort of Intimacy that is common (for example) between Boys and Dogs; whereas Mr Francis Lloyd fancied that I might win the Ribbon at the Salford Horse and Livestock Fair, and earn him a considerable Bonus per pound besides, when the time came after to sell me. As for Sam, he was, as I should express it now, of that very Age which cannot quite Peep over the Sill of adulthood but believes it to be little more than an Extension of childish existence—only on Tip-toes. Thus he had no conception whatsoever of these his Uncle’s plans. And as for the Uncle—why, if there was a thing he thought Less of than his nephew’s connections with one of his Pigs, I cannot imagine it.