Читать книгу Burning Down the House - Russell Wangersky - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFOUR

Some firefighters preferred the jump seats, the two seats that left you facing backwards behind the driver, your back already settled into the racked breathing apparatus so you could pull the straps into place tight and stand up with a jerk, the cylinders settled into place on your back. Winter or summer, in Wolfville I rode the tailgate of the lead pumper if I could get there in time. I liked the tailgate, liked the way it flung me upwards every time the rear wheels went over a big bump—like the back row of seats in the school bus—and I liked the way I was right there, ready to put my armthrough the loose loop at the bottom of the attack line. Pull that loop and two hundred feet of yellow fabric hose would spill off the pumper in a heap, more than enough to reach most fires, even with the pumper at a safe distance.

Enough hose to let me stand there just out of reach of the flames for those first few moments when I was waiting for water, while the pump operator yanked open the toggle for the discharge and filled the hose, one hundred pounds per square inch of water coming out the nozzle. I’d brace myself, feet wide apart, hose curled into my stomach, waiting for the urgent hiss of air that meant water was on the way.

I was learning all the time—and not all of the lessons were about the mechanics of fighting fires, either. Plenty of the lessons were simply about the rules of being a firefighter, and that’s different.

In a fire at a hardware store, one of the Wolfville fire captains, Jim Sponagle, had a panel of vinyl wallpaper peel off its glued backing and drape itself, burning, over the top of his helmet and the facepiece of his breathing gear. When he pawed at the burning paper, it would only come away in smears, so that he was looking out through a nimbus of fire. His gloves were covered in burning vinyl too.

A hardware store can become a frightening maze in a hurry. It’s strange how quickly the ordered rows of sale items can start reaching for your sleeves and for your air tank hoses. As a shopper, you’d never worry about bumping into the shelves while walking the narrow aisles, but it was amazing how the straight line you would walk along without touching anything could become a narrow slot that was almost impossible to navigate.

A hardware store fire was the first occasion I ever heard spray paint cans exploding, a bright, sharp crack of overheated metal, and then the deeper whumps as gallons of house paint blew their lids all along a shelving unit. It was a kaleidoscope of sound, that fire—the explosions, the crackling wood, the body slam of the plate glass front window suddenly reaching its thermal limit and blowing out all over the parking lot in great, long, reaching shards.

Later on, when we were outside putting water in through the broken front window, we heard the rifle and shotgun bullets exploding, small uneven fusillades of ammunition. By then it was the kind of fire that firefighters call a “surround and drown,” the kind where you set up the big hoses and pour water on from the outside until the smoke devolves through black and brown and yellow to the thin, winning white of steam, water on hot charcoal.

No one talked about the sheer wonder of it, about the explosions that shot the paint can lids roaring upwards, about the thud you could feel inside when they blew, or even about the way the great gouts of paint shot straight up and burst into instant bright flame in the superheated air above. No one mentioned the way the column of black smoke stood out alien against the bright blue of the sky, or how, from a distance, that same smoke drew your eye the way an asterisk does at the end of a word, footnoting the sky.

At another store fire, my partner and I were crawling on our hands and knees, dragging a hose towards the back of the building, towards the glow of a fire that had started in a storeroom. Then the flames burst out and ran back across the ceiling above us before we could get to the seat of the fire, before we could even crack the nozzle and hear that first eager rush of air. It moved fast, boiling out and above us in an upside-down wave. As the ceiling lit on fire, we started crawling backwards, and I got the other firefighter’s boot square in my face mask. We detoured along the outside edge of the office, glass shattering and bottles bursting, the room suddenly full of smoke and noise.

That was frightening enough. I can imagine how much more frightening it must have been for Captain Sponagle, working the same kind of fire scene and ending up wearing wallpaper, seeing only fire through his mask. It must have been terrifying, all that vinyl-fronted paper stuck to his face like burning glue.

But we didn’t talk about it. All our conversation was practical and thorough, and I learned repeatedly that, when it came to talking, no one really did it at all. Captain Sponagle found a way to talk about the experience to new firefighters, as if a face full of burning wallpaper could actually be pretty damned funny, the kind of story others could trot out every few months or so, blaming him for ruining the facepiece of the breathing gear.

Back then, everything was a first for me—and that was the first time I wondered whether everyone, from probationary firefighter up to fire captain, could be afraid. But no one ever said a word. We didn’t talk about being scared—and I certainly wasn’t going to say anything, not when I was surrounded by many guys who could, it seemed, do anything. My job was to listen and learn, and I was like a sponge, soaking up everything the other firefighters said—and noticing the things they didn’t mention as well. No one talked about fear and, more than that, we didn’t talk about mistakes either.

And it would stay that way.

After a fire call, I’d make sure the trucks were cleaned up and the straps on the air packs were fully extended and the Pepsi machine was full, and I’d move around the other firefighters, all of them loose-limbed and relaxed and leaning against the counter while they drank their coffee.

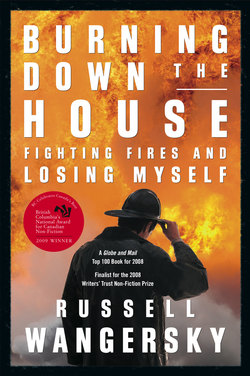

There is a picture of me that was taken that first summer firefighting. In it, I look strangely too narrow for my own body, as if I had finished growing but hadn’t yet found a way to put any substance into myself. In the picture, I’m leaning against the brick side of Wolfville’s train station, a station like a hundred others Canadian National built across the country, small-roomed and Victorian, with steep, gabled slate roofs, the slates set on the diagonal so that they look like diamonds or, when wet, the side of a lizard.

Jutting out from under my sweater, the object closest to the camera is my pager, a big rectangular Motorola that went everywhere with me. Every time the pager dug into me, every time I realized it was there, I would hope it was on the verge of going off. I’d already started doing the little planning flick in my head that would go on for years—deciding how I’d get to the fire station if the pager went off, how long it would take me, whether I’d be able to get there in time to catch the first truck before it rumbled away.

I look posed, leaning against that wall, and I realize now that I look remarkably unprepared for anything. Smug, as if I was sure I already knew everything there was to know, a look that was at the same time betrayed by the soft, unformed edges of my face. A face still forming up, halfway to the face it would eventually be, but already holding hints of what might be strain.

Back at the truck, the fire chief was blunt.

“Noxzema job,” he said gruffly, meaning he’d swipe a finger into a blue bottle of Noxzema and fill both his nostrils before he got close to the body, in an effort to keep from being hit too hard by the stench of the early stages of putrefaction. It doesn’t take long in summer, not when it’s someone who’s been out in the weather for three days or so.

Noxzema sounds like a practical-enough solution, but it is never really as easy as that; there’s no simple way to keep it all away, especially not that smell. The smell of death is something we all seem hard-wired to shy away from. If you smell it and have no idea what the stink is, you’ll still be overcome with the urge to stay away. It can overwhelm curiosity, and it’s a smell that clings, that sticks in your nose the way burnt cedar does, as if certain-shaped molecules find certain-shaped receptors and can’t seem to disengage.

Then there’s “the body” itself. I learned to use general, less human terms, and even those words get updated, changing over time as people fight over what’s suitable. You can almost place a firefighter’s training in time by what words he uses. Once, the people injured at accidents were called “victims.” I still fall back on that one. Then they became “casualties,” because “victims” always sounded like whoever you were talking about was already dead. But what we really needed was a good, neutral description. It’s easier when the person is just “a body,” a simple thing like a couch or a table or a box spring, instead of “the baby” or “Elizabeth” or anything that makes you think of warm skin.

It was a small clearing, hardly more than twenty feet square, a small notch in the forest sloped precipitously enough that, by sitting at the top edge, the spruce and pine below didn’t reach high enough to block my view of the valley. It was the kind of place you trip over sometimes by chance, far enough away from the path that you can imagine no one else has ever been there. The kind of place you might hold in your memory as a respite, as its own relaxation; the kind of place that, once found, you would go back to over and over again, either in person or in memory. The place you and a girlfriend would visit some afternoon and always remember. A postage stamp of the world that becomes your property by its mere discovery.

She had a blanket and a knapsack—the remains of a picnic, an empty pop bottle and wrappers. A few stuffed animals, and her jacket, folded neatly in a square. Pill bottles. She had taken off her shoes— brown flat shoes, the leather in a woven waffle pattern across the toes.

After we left, someone would have gathered up all the personal effects and litter, and in a week or so the grass would slowly have found its way back upright, looking as untrammelled as ever.