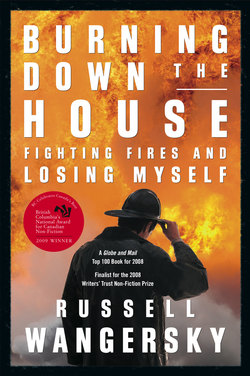

Читать книгу Burning Down the House - Russell Wangersky - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPrologue

Firefighting was something I had dreamed of doing, something I had thought was an impossible goal. I was always small for my age and nearsighted to boot, not at all the physical type fire departments generally demand. I would watch the fire trucks passing the Halifax house where I grew up, and if the trucks stopped close enough and their sirens cut off I’d head out to hunt for the fire. I read books about firefighters, living vicariously through the words, sure that I would never be able to do that work myself.

As a result of chance and timing, I got to fight fires, and eventually both my size and my eyesight became their own kind of advantage. Small and light, I fit into many places where larger firefighters couldn’t work—inside crushed cars, in confined spaces, in any spot where bulk hindered. My poor eyesight also had a peculiar benefit: while some people become claustrophobic in breathing gear and smoke, I was used to working without depending on my eyes. I was already accustomed to navigating by sound, to listening, to understanding that my eyes could lie.

Fighting fires and going to accident scenes is a sensory wonder, the most amazing and visceral experience anyone could ask for, but what had been a dream became a kind of personal nightmare, as bit by bit the underpinnings of wonder and heroics fell away. I was left with horrors I still live with now, horrors that can, occasionally, sneak up on me when I don’t expect them, smashing my confidence and leaving me unable to control my temper or my fears.

At first I believed it would all be simple: people would call us, we would arrive on a scene with our training and our equipment, and we would help, because that was what we were supposed to do. The truth is infinitely more complicated than that, and helping sometimes ends up being far more subjective than it ever seems on paper.

I didn’t actually help as much as I thought I would be able to. More than anything else, many actions were, in retrospect, best attempts and half measures. Bit by bit I realized that the heroic gloss of firefighting hid—at least for me—more and more self-doubt with every passing fire and accident scene.

It wasn’t that way at first. Only a few months into firefighting, I found myself in that very brief honeymoon where I actually believed I knew everything I needed to know. I believed that, between my equipment and the training, I had more than enough to keep myself safe. It’s a feeling that would occasionally come back over the years I was fighting fires, but it was one that was always quickly dashed. Whenever you’re up, there’s going to be something to knock you down; you can do your best with physical safety, but you can’t always deal with the rest. They don’t make equipment to protect your mental health, although the fire service has gotten far better over the years at providing counselling and care for its members.

Each step into the fire service took me two steps farther away from everyone else’s world, farther into a place that few people besides emergency workers will truly comprehend. I took every step wide-eyed with wonder, as careful as I could be not to break any unwritten code; firefighters have their own superstitions and fears, and it’s easy, early on, to step into mistakes you know nothing about.

I don’t know exactly when the nightmares started, I just know I didn’t expect them and that they haven’t stopped—and I wonder if they ever will. I know they are made from the building blocks of hundreds of fire calls and accidents, from the mundane to the horrifying, but I don’t know which specific calls are the cause, or how the pieces will end up fitting together. I know that I can expect, regularly, to be jarred out of sleep, terrified, and that I may never fully escape the damage done. Within the first few months on the trucks I was seeing people ripped apart into their constituent bits, a sort of deconstruction that makes you look at your own hands and feet differently. Before I turned twenty-four, I would see how a 100-kilometre-per-hour head-on crash could break both a person’s wrists so that their hands hung limp as if they were cloth, forced to fold against the bias. I would see people with their heads torn off. High-speed rollovers. Fuel tanker wrecks. I’d witness the way camper trailers blow apart into quarter-inch plywood splinters when they roll over at high speed on the highway.

I learned quickly that when I was with other firefighters, there were things I was allowed to talk about and ways that I was allowed to talk about them. There were other things I just wasn’t supposed to mention.

When I finally stopped firefighting I was close to forty, the deputy chief of a thirty-member department. When I started I was twenty-one, and about to get married. Most people at twenty-one are getting ready for their life, told to hope for happily-ever-after and a fairy-tale ending. At twenty-one, you should be looking at clean wallpaper and fresh starts; I was seeing broken limbs and people taking their last few breaths after a cardiac arrest.

The job caught up with me eventually, and, inside my head at least, it hit me far more harshly than I think I deserved.