Читать книгу Seeking God with Saint John Henry Newman - Ryan J. Marr - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

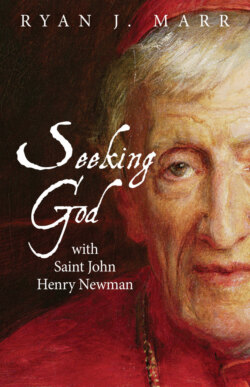

The Life of Newman

ОглавлениеAt the beatification ceremony for Blessed Dominic Barberi — the Italian Passionist priest who received Newman into the Catholic Church — Pope Paul VI took time in his address to touch briefly upon the enduring legacy of Newman. Specifically, the pope described Newman as one who, “guided solely by love of the truth and fidelity to Christ, traced an itinerary, the most toilsome, but also the greatest, the most meaningful, the most conclusive, that human thought ever travelled during the [nineteenth] century, indeed one might say during the modern era, to arrive at the fullness of wisdom and of peace.”17 Paul VI’s remarks memorably encapsulate the dramatic character of Newman’s arduous spiritual journey, which could succinctly be described as an unwavering search for the truth.

When Newman was born, on February 21, 1801, no one could have predicted that this infant would eventually become the greatest English-speaking Roman Catholic theologian of his time. Newman was born to practicing, though not overly zealous, Anglican parents — John and Jemima Newman (neé Fourdrinier). For our purposes, it’s unnecessary to dwell at length upon the details of John Henry’s childhood, except to note that there was nothing noticeably unconventional about his upbringing. Newman’s religious formation was largely in the mode of “Bible Religion” — a term that he used later in his life to describe “the national religion of England.”18 This way of practicing the Faith revolved around devotional reading of the Bible, both in a communal setting in church and privately at home. Whatever limitations there may have been to this approach, the Bible-centered religion of Newman’s youth would have a lifelong impact on his witness to the Gospel, as evidenced perhaps most markedly in the way that his sermons are saturated with the language of Sacred Scripture.

As a young man, Newman enrolled at Trinity College, Oxford. His time as a student was a mixed bag: Although he thoroughly enjoyed the intellectual stimulation of university life, he did not fit in socially, largely on account of his unwillingness to participate in the drinking bouts that occupied his peers. Social ostracization at the college had its advantages, however, in that Newman had ample time to study. Unfortunately, his studiousness backfired on him in 1821, when he drove himself to the brink of a mental breakdown by overpreparing for his examinations. As a result, he fared poorly on the exams, ending up off the honors list for mathematics and in the lower division of the second class — or “under the line” — for classics. Feeling himself an embarrassment to his family, Newman feared that his hopes for a fellowship at Oxford had been lost. In April of 1822, however, he received the surprising news that he had been elected a fellow of Oriel College. Apparently, Newman’s intellectual prowess as manifested in his written work had outweighed any concerns raised by his performance on the exams.

Newman later described his earning this fellowship as “the turning point of his life,”19 but it could just as aptly be considered a key turning point in the history of the Church of England. For it was during his time as a fellow at Oriel that Newman became the de facto leader of the Oxford movement. This was an effort led by several key Oxford figures to return the Church of England to its Catholic roots, by integrating some pre-Reformation devotional and liturgical traditions into contemporary Anglican practice. The Oxford movement leaders also mounted a protest against the incursion of state authority in the decision-making of the Church. In their view, the Church as an apostolic community was accountable to God alone. Permitting the state to have any role in ecclesiastical governance was, for them, a compromise of the Church’s fundamental identity. Newman and his Oxford movement confrères disseminated their ideas through a series of pamphlets, or Tracts for the Times, which is how they came to be known as Tractarians.

For a time, the Tractarians made significant headway in bringing about the reforms they sought, but eventually Newman lost his zeal for this effort — in part because of the negative reaction to one of his published tracts (Tract 90), but even more significantly because he started to doubt his conviction that the Church of England was truly catholic and apostolic. During the 1830s, Newman had pressed the argument that Anglicanism struck a via media between the errors of Protestantism on one side, and the excesses of Romanism on the other. At this stage in his life, Newman claimed that the Church of England was apostolic because it held fast to the creedal commitments of the early Church. In his view, Protestant communities neglected key parts of the apostolic tradition, while Roman Catholicism added to it. However, certain developments in the late 1830s — including the Church of England’s decision to share a bishopric in Jerusalem with Lutherans — caused Newman to reconsider the whole question of where the one Church of Christ could be found.20 Over the next few years, his doubts accelerated, such that by 1841 Newman was on his “deathbed” regarding his membership in the Anglican Church.21

The following year, Newman withdrew with some of his closest friends to Littlemore, outside Oxford, where he and this circle of followers began to practice a form of life that closely resembled traditional monasticism. On September 25, 1843, he preached his last Anglican sermon, “The Parting of Friends,” at the quaint parish church he had designed in Littlemore. Two years later, on October 9, 1845, he was received into the Roman Catholic Church by Father Dominic Barberi, who was serving during that time as a missionary in England. Newman said his entry into the Catholic Church was “like coming into port after a rough sea.”22 Despite undergoing many personal trials in the years that followed, he never regretted his decision to swim the Tiber.