Читать книгу Seeking God with Saint John Henry Newman - Ryan J. Marr - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

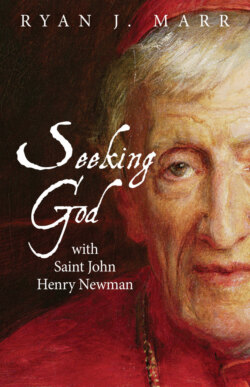

Newman’s Catholic Years

ОглавлениеAs intimated in the previous section, Newman’s time as a Roman Catholic was characterized by a series of personal difficulties and professional disappointments. Newman began seminary studies in Rome in the fall of 1846, before being ordained to the Catholic priesthood on May 30, 1847. After a period of ministry in England, he relocated to Dublin in 1854 to serve as the first rector of the newly established Catholic University of Ireland, only to resign from that position a few years later, on account of the stress that he was experiencing and also because he sensed that the Irish bishops were not fully supportive of his vision for the institution. At the end of that decade, Newman found himself increasingly under the microscope of the English hierarchy due to an article that he had written recommending that bishops consult the lay faithful on matters of doctrine. Bishop Brown of Newport even went so far as to report Newman to Roman authorities on suspicion of heresy — a charge that wasn’t completely cleared up until several years later. Newman also had to fight a frivolous lawsuit leveled against him by a corrupt ex-priest, lost his closest friend to an early death, and regularly butted heads with the primate of England — his sometime friend and fellow convert Archbishop Henry Manning.

The list could go on, and things got so bad that, for a time, many Englanders wondered whether Newman would return to the religious communion of his youth. When Newman got wind of this rumor, he squashed it forcefully, writing that he had never “had one moment’s wavering of trust in the Catholic Church since [being] received into her fold” and adding that he had still “an unclouded faith in her creed in all its articles; a supreme satisfaction in her worship, discipline, and teaching; and an eager longing and a hope against hope that the many dear friends whom I have left in Protestantism may be partakers of my happiness.”23 For Newman, the Catholic Church was first and foremost a gracious gift given by God in order to bring us salvation, but she also exists, he believed, to sustain us through the storms of life. To commit oneself to life in the Church, therefore, is part of what it means to practice trust in God’s providential care.

This abandonment to Divine Providence that Newman practiced constantly informed his thought about life in the Church and, in turn, the counsel that he gave to others regarding how to live as members of the Body of Christ. As an example, we can look at how Newman navigated the events surrounding the First Vatican Council (1869–1870), which was an exceedingly trying time for him. At this council, a certain group of bishops sought to ratify a strongly worded statement regarding the pope’s power to teach infallibly (i.e., without error) on matters of faith and morals. In their view, such a definition would reinforce the Church’s teaching authority and thus help to protect Catholics against the winds of philosophical skepticism that were sweeping across Europe in the nineteenth century.

Since becoming Catholic, Newman had believed in the pope’s infallibility as a theological opinion. Nevertheless, he thought that this group of bishops was acting recklessly by insisting on a strongly worded definition without giving due attention to the complexities of Church history and without showing sufficient concern for the consciences of those who had difficulty with the idea. In short, Newman thought the Church needed more time to work out a definition of the doctrine that clearly specified the limits of infallibility in light of certain historical instances that appeared to stand in tension with the idea — for instance, the fact that a few popes had privately held theological convictions that were later condemned by the Church.

When the bishops at Vatican I ended up approving a definition of papal infallibility, Newman said that he was pleased with its moderation. He believed that the extreme party had not gotten its way but that the Holy Spirit had again guided the Church in her deliberation over a disputed theological question. Though Newman was relieved, in the years following Vatican I numerous friends and acquaintances looked to him for counsel as they struggled to make sense of the definition and its implications. And this gets to the key point for our purposes. Rather than dismissing their concerns, Newman encouraged these individuals to turn to God when they were troubled in conscience by what they were witnessing in the Church. In an 1871 letter to Alfred Plummer, for instance, Newman wrote:

Another consideration has struck me forcibly, and that is, that, looking at early history, it would seem as if the Church moved on to the perfect truth by various successive declarations, alternately in contrary directions, and thus perfecting, completing, supplying each other. Let us have a little faith in her, I say. Pius [IX] is not the last of the Popes — the fourth Council modified the third, the fifth, the fourth. … Let us be patient, let us have faith, and a new Pope, and a re-assembled Council may trim the boat.24

In other words, God has guided the Church this far amid many ferocious storms, and we can trust that God will continue to guide her in the years to come. Our belief in the indefectibility of the Church — i.e., that the gates of hell will not prevail against her (see Mt 16:18) — does not rest on the greatness of our strength, or on the natural gifts of our bishops, but solely on the promises of God. It is God who preserves the Church, and thus, we should seek to have the kind of patience that Newman recommends whenever we find ourselves disturbed by the circumstances around us.

As for our own experience of the Church, today we are less likely to fret over such issues as papal infallibility or the political machinations that took place at Vatican I, but, for different reasons, it can still be difficult to live as a member of the Body of Christ. Alongside the challenge of intellectually making sense of the Faith, contemporary Catholics may struggle with the hypocrisy that we see in the Church or with the abuse perpetrated by some who were appointed to be our pastors. Regardless of which factors cause you to question your faith, Newman’s example can serve as a source of inspiration. Newman dealt with heavy-handed bishops, and at times he was troubled by the narrow-mindedness that he perceived on the part of certain outspoken Catholics.25 But he never contemplated leaving the Church. Besides his sense that God was ultimately in control, Newman was also convinced that Christianity was inherently a social religion. In terms of living out the Faith, then, there are no Lone Ranger disciples. We come to know the love of God not in spite of but precisely through our communion with our brothers and sisters in Christ. As Newman once observed, “the love of our private friends is the only preparatory exercise for the love of all men.”26 And there is no more intimate form of friendship, arguably, than walking together as baptized members of Christ’s Body. Life in the Church is far from perfect, but by remaining committed to the family of God, we will learn to sacrifice our selfish desires in humble submission to others who are themselves imperfect.

Newman did not merely preach these ideas; he also modeled them — most notably, in his leadership of the Oratory community of priests that he established in Birmingham. Since its founding in 1849, the Birmingham Oratory has been a shining testimony to Newman’s theology of friendship, which is rooted in shared worship of the Triune God. From Newman’s vantage point, the love we have for our friends and our relationship to God are inextricably bound together. As 1 John 4:20 warns, “If any one says, ‘I love God,’ and hates his brother, he is a liar; for he who does not love his brother whom he has seen, cannot love God whom he has not seen.” In a similar vein, Newman wrote:

Should God call upon us to preach to the world, surely we must obey His call; but at present, let us do what lies before us. Little children, let us love one another. Let us be meek and gentle; let us think before we speak; let us try to improve our talents in private life; let us do good, not hoping for a return, and avoiding all display before men. Well may I so exhort you at this [Christmas] season, when we have so lately partaken together the Blessed Sacrament which binds us to mutual love, and gives us strength to practice it. Let us not forget the promise we then made, or the grace we then received. We are not our own; we are bought with the blood of Christ; we are consecrated to be temples of the Holy Spirit, an unutterable privilege, which is weighty enough to sink us with shame at our unworthiness, did it not the while strengthen us by the aid itself imparts, to bear its extreme costliness.27

Newman’s pastoral heart shines forth brightly in this exhortation. For him, heeding the call of God meant, first and foremost, embodying a life of meekness, mutual love, and unassuming beneficence toward others. By following this “little way,” Newman did end up “preach[ing] to the world,” but he did not start with this latter accomplishment in view. He began with friendship and humble service to others and then trusted God to multiply the fruits of these small offerings, and God clearly did.

In 1890, after nearly seven decades of humble service in the kingdom of God, Newman passed away after a brief bout with pneumonia. In his will, Newman had made provisions for a small memorial plaque to be installed at the Oratory, upon which were inscribed the words Ex umbris et imaginibus in veritatem — “Out of shadows and images into truth.” After a lifetime of seeking the truth, Newman had finally reached his home, the loving embrace of his heavenly Father. The epitaph that Newman chose for his funerary marker was eventually incorporated into the collect for his feast day; it is a moving prayer that can be offered for a variety of intentions, but especially when asking for the grace to imitate his example:

O God, who bestowed on the Priest Saint John Henry Newman the grace to follow your kindly light and find peace in your Church; graciously grant that, through his intercession and example, we may be led out of shadows and images into the fulness of your truth. Through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son, who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever.28