Читать книгу Deluge - S. Fowler Wright - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER V

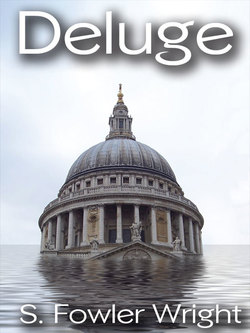

Claire Arlington stood on the edge of what had once been a steep hillside in the Upper Cotswolds. Now it was lapped by a tide that rose within eighty feet of the summit.

Steep though the slope might be, it was still green with the sparse Cotswold herbage, which grew so thinly that the white chalk showed between it, and yet the sleek, long-barrelled cow that grazed on the cliff-top was evidence that it was not lacking in nourishment.

Claire was not thinking of cliff or cow, but gazing with troubled eyes upon the desolation of a quiet sea.

Looking north, there was no sign of land, though a whitening of broken water here and there beneath her told of shallows which a lower tide would leave uncovered.

There was no sign of the Malverns. If any of the higher lands of Wales had escaped the deluge, they were too low or too distant for her sight to reach them.

Only to the north-east was there at times a doubtful hint of land. If she were only sure—She was a strong swimmer. Once she had tried to cross the Dover Straits, and had been baulked by the tide when within but a short distance of the French coast. If she could only be sure that land were there—or of how far it might be.

It was but a few weeks ago—she had not counted the days, for count of days had ceased to matter—since she had spent long hours of darkness floating as best she might amidst the buffeting of continual waves, to find, when the dawn came that she was drifting fast towards a vision of green land, and then to realise that the current which bore her near would sweep her past it, and then to battle backward, yard by yard, until the sun had risen high above the horizon, and she was aware at last that she was clear of the current’s force and each tired stroke decreased the distance to the waiting land.

Then the land on which she climbed had seemed the most blessed thing for which a living creature could pray; and now she loathed it, so that death itself might seem less bitter.

Death? No; her heart told her that she had no will that way, whatever life might mean.

She stood there for a long time silent, gazing at the sea, the while her mind went back to recollection of all that had happened since she had survived that night in which so many millions must have perished.

Her husband among them—there was no possible hope that he could have lived. An invalid, awaiting an operation in the nursing home in Cheltenham, she would have been with him on the previous day, if the great storm had not made it impossible. She felt no keen regret. The horror had been too great. It had numbed her mind. And she knew that though she had loved him in a way, and there had been no differences between them, the bond had not been as strong as she had been taught such bonds should be. Pity rather than love—pity for a man maimed and disfigured in the prime of life—and then he had been querulous, and exacting, and jealous—so she knew, though she did not let the thought take form. But she was glad that the baby had not lived—for she could not have saved it—and how she had grieved when she had been told—but who could have foreseen?

Yes, there was no chance that he lived; not Cheltenham only, but all the land beyond—Ireland, perhaps—had gone. It was only a few days ago that a south-west wind had risen, and she had watched the great Atlantic rollers sweeping past, and felt the high surf drench her, even at that height, as she had seen and felt upon the Cornish headlands in the days gone by.

Yes, that life had left her, with all its obligations, all its occupations, its loves and friendships—perhaps she would have regretted them more keenly had not the new urgencies—but anyway, they were gone, and here she stood—free.

Free!—a fierce anger lit the sombre gaze of wild grey eyes, and strong teeth bit a bleeding lip as the thought stirred her. She was the Eve—perhaps the only Eve—of the new world, and her sole thought was of risking life itself to reach that doubtful streak of land, and so escape her heritage—or perhaps to gain it?

If she could only be sure that land were there! For she knew quite clearly that whatever life might hold she did not mean to die. Then did she mean to yield? Like a trapped mouse her mind went backward and forward to find escape from a problem which gave her no solution.

She recalled how she had climbed the hill from the bay where she had landed, and found a cleft in the hilltop where three cows crouched and shivered, and how they had come to her, as though for protection from the terror of a failing world, and she had drawn milk from one of them, and slept on the short turf in the warmth of the rising sun, and wakened to know that the noon was past, and to find the cows in a recovered serenity grazing quietly around her (and the cows were hers, let Jephson say what he would!), and so, with another meal of new milk to ease the thirst with which she woke, and clothed only in the bathing dress in which she had landed, she had set out to explore the land that the floods had spared, and seek for further food, and garments, and shelter for the night to be.