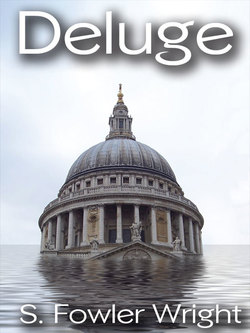

Читать книгу Deluge - S. Fowler Wright - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPREFACE

TO THE SECOND EDITION

The issue of a second edition of this book, before its sequel is published, provides an earlier opportunity of answering some of the criticisms which it has provoked, most of which were based upon the supposition that it was written in a spirit of propaganda, which is a mistake.

It was, in fact, written somewhat randomly, allowing circumstances and character to develop to what ends they would, which is the way of life, and should, I think, be that of fiction also. Its conclusion—if such it can be called, being the event of a critical moment, which must work out its further and most uncertain issues—was neither foreseen nor intended.

Imagining a quite probable physical incidence, and certain people to be involved therein, I was only concerned to observe the interaction of character and circumstance, under conditions which would never be exactly duplicated. If such people, under such circumstances, would not act in such manner, the book is open to legitimate criticism, but not otherwise. As to that, readers must judge for themselves. But the actions must be regarded as individual, not typical.

One American reviewer challenges me definitely on this ground, stating that no woman would act as Helen does in the last chapter, and that I show ignorance of feminine psychology. Women may be as inevitable as the moon, but, like her, they act with a delusive appearance of inconstancy, and the error may not be mine.

A woman has just brought an action against her husband in the Turkish courts on the ground that he failed to take a second wife within a reasonable interval after his marriage to herself, which she had a right to expect from one in his social position. Does he suppose, she asks, that she will be content to consort with servants indefinitely?

I notice that this line of criticism reaches me only from American sources. “A frequent change of wife,” in Sir Owen Seaman’s delightful phrase, is one of the basic privileges of American citizenship, which we of the old world, bound to our monotonous loyalties, can only admire from a distance; but they are extremely particular that neither they nor their neighbours shall have more than one at a time.

I am puzzled by both these characteristics. I have a strong preference for keeping the wife I have, and if my neighbour were to tell me that he has half a dozen I should hear him with sympathy, but my mind would not be disturbed by any violent reaction. It might be supposed that an American citizen, having emerged once or twice from the disaster of marriage, would prefer to take his remaining wives in bulk rather than seriatim, and get through them as quickly as possible. Perhaps he would; and the objection may be on the side of the women only. A woman commonly has a retail mind.

In England, one (otherwise too-kindly) reviewer considers that the book contains evidences of “ferocious prejudices.”

Now I am not without prejudices (who is?), but if I were told that I have fewer than any other inhabitant of these islands, I should be less surprised than if almost any other singularity were alleged against me.

I believe that human life has some value; and I am prejudiced in favour of populating the British Empire.

I am equally prejudiced against walking across Oxford Circus with my eyes closed at midday, and reducing our fleet while our land goes out of cultivation, although I realise that either folly may be perpetrated without inevitable penalty following.

I am prejudiced in the belief that the death of one careless chauffeur daily in the hangman’s shed, however regrettable, would be less so than is the death of seven careless pedestrians daily on the open road. (The actual road fatalities in England now number fourteen a day, not seven, but half of these are motorists who kill themselves or each other.)

I am also prejudiced against the opinion of the Home Secretary that the perils and abuses of road traffic will increase indefinitely, because I have not observed that it is in the nature of pendulums to continue to swing in the same direction.

But my prejudices are very few, and are easily challenged. I am prejudiced in the beliefs that the earth is spherical, and that Marie Stopes is intellectually subnormal, yet if I were told that she is capable of a logical argument, or that the earth is flat, I should approach either proposition with an alert curiosity and a very open mind.

A correspondent reproaches me for alluding to “the mercy of another war” as though it implied either callousness or stupidity. War is, in many aspects, the supreme evil; and to initiate it is the supreme crime. It may be strongly, though not conclusively argued, that it is incompatible with Christianity under every circumstance. But there are evils of peace, also, which are no less deadly because they are slower and less dramatic in operation; and if war be permanently avoidable without national degeneration, we must carry the high spirit of conflict into the years of peace, which we have failed to do.

The end of the war left us with a Government assuring us that we were too tired for further effort, and ordering the retreat to be sounded. We were to reap the blessings of peace, but we were to make no effort to cultivate them. We were to talk about homes for heroes rather than to exert ourselves to build them. We were to recover prosperity, not by hard work, but by increasing each other’s wages indefinitely.

Naturally, privations followed.

Pitiless taxation and currency manoeuvres may have kept some parts of the nation in continued comfort, but for the community as a whole they proved an obstructive curse. Such are the common sequels of prolonged war, and the politicians who are responsible for them will tell us complacently that they are inevitable. But is there any historical record of the difficulties of post-martial years being attacked with the national spirit which is provoked by the impact of a dangerous enmity?

Consider the question of housing. The end of the war found us deficient both in quantity and condition. There was no proper accommodation for the millions of men who were returning to civil life from tent and trench and shipboard. There were no roofs beneath which they could form the homes which the nation needed, with the women who were waiting for them, or whom they had married already. Can it be said that we were lacking in the labour or skill to build the houses they needed, or that it was beyond possibility to procure the necessary materials?

Suppose that at the crisis of war, in the spring of 1918, these houses had suddenly been realised as a condition of victory. Suppose that we had known certainly that if half a million houses could be solidly erected in six months we should win the war, and if there were one short we should lose it. Would Mr Lloyd George have been content to make a “homes for heroes” speech, and then such a bargain with those who were expert to build them as would enable them, from brickmaker to bricklayer, to live comfortably while working slackly, and to debar anyone else from assisting their operations?

Would it have been tolerated, had the result of the war depended upon their occupation, that thousands of houses, whether large or small, should have been held empty to satisfy the private greed of their owners?

There are many instances of nations that have maintained themselves through centuries of successful war. In all history, there is no record of any nation that has retained its character or vitality through centuries of successful peace. If we would venture that higher and harder enterprise with reasonable hope of achievement, we must first recognise its conditions and dangers, which we show no disposition to do, and we shall need some better guidance than will come from the muddled wobblings of Dean Inge, or the vicious cowardice of the gospel of Marie Stopes.

We need not observe these facts in any spirit of pessimism, for they are only formidable the while we fail to observe them. But it would be foolish to ignore their significance. It is not a trivial circumstance that the English post-office, which once prided itself on the certainty with which it would deliver any communication entrusted to it, however badly addressed, now takes an equal pride in the ingenuity with which it can find reasons for failing to do so. But it will not be the first time that England has seen evil days and survived them.

Quiet, uncomplaining, oppressed with a weight of taxation which is without excuse, as it is without precedent, shamefully told that the payment of these exactions is more important than their children’s lives, there are still in England, unless my faith is mistaken, a million of uncorrupted homes, where children are received with love, and privations are met with courage.

The pressure of unjust taxation may yet find a Hampden to resist it. A materialistic “science” may yet rouse a prophet to deride its superstitions, and to denounce its counsels of degradation.

However cunningly entrenched may be the bureaucracy which controls us, it is a fundamental law that it cannot endure unless its spirit be one of service rather than of acquisition.

Feudalism was impregnable until its ideal of service faltered. The monasteries would have endured until today, had they been content to express the ideality which conceived them.

Our “captains of industry” may become the rulers of their race, or they may end beneath the feet of a howling mob. The decision does not rest with the mob, nor with chance, nor with a settled destiny. It rests with them. If they be more concerned for their own wealth than for the welfare of those they lead, even the stupidity of the Labour party (which is almost absolute) will be sufficient for their undoing.

We may contemplate the probability that our civilisation may be swept away by physical catastrophe, and be succeeded by a period of simpler and more primitive life, from which new complexities will develop, without pessimism, and, if we understand the nature and purpose of human life intelligently, without regret.

Even if this civilisation were realised as the highest that the earth has borne, and could it be freed from various sinister practices, (such as that of usury), which are so woven into its fabric that it may be doubted whether it could survive their removal, we might still contemplate its conclusion with equanimity, or even with satisfaction.

Having won a game, we do not desire to remain static in victory. We clear the field for the contest which is sure to follow. But whether our civilisation be of such quality that it could be accounted pessimistic, from any standpoint, to anticipate its destruction, is not beyond argument. It might be considered evidence of an exceptionally sanguine temperament.

—S. Fowler Wright