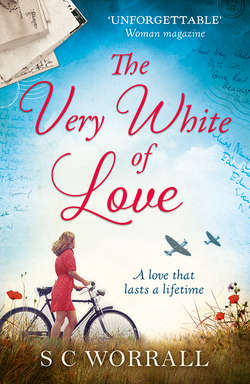

Читать книгу The Very White of Love: the heartbreaking love story that everyone is talking about! - S Worrall C - Страница 10

Оглавление19 SEPTEMBER 1938

Whichert House

Dear Aunt D.,

I’ve fallen madly in love with Nancy Claire Whelan. You’ve every right to laugh when you read that, but I’m terribly happy to have found someone so fond of me, who leaves everyone else I’ve met in the cold. I’m sure you’ve seen her riding her bicycle about town. She lives down the road from you at Blythe Cottage. She is an only child – and a redhead! Her father is in the Revenue Department of the civil service. She was at school in Oxford so she knows it well and she has also lived in France and Germany. She speaks the languages, she sings and acts, she’s intelligent, pretty and, a thing I envy her for, has a good and interesting job.

He lifts the pen and looks out of the window. Outside, a soft rain is falling. Just thinking of her makes him want to dance around the room. But he doesn’t want to tell his aunt everything.

Meeting her was a strange and fateful coincidence . . .

Martin opens his eyes. There’s a thudding pain in his head, as though someone has inserted a fist into the back of his skull and is trying to force the knuckles out through his eyeballs. He groans and rolls over. Fragments of the previous evening float to the surface of his alcohol-curdled brain, like bubbles in a pond. They’d started at the Red Lion, across the street from Whichert House, tankard after tankard of warm beer followed by shots of Bell’s. Hugh Saunders, who is also up at Oxford, had driven over from Gerrards Cross, one of a network of friends in south Buckinghamshire Martin got to know while staying with his Aunt Dorothy during the school holidays. As children, they rode bikes together, played golf and tennis, and later courted the same girls. A couple of old friends had also come down from Aylesbury. It’s the holidays. Four weeks away from Oxford University where Martin is about to start his second year. Four weeks with no essays to write or tutorials to attend. Aunt D. and the rest of the family are off fly-fishing in Scotland. He can come and go as he pleases, stay up as late as he wants, drink too much.

From the Red Lion they’d driven to the Royal Standard of England: a cavalcade of cars swerving down darkened lanes. Hugh bet him half a crown that he’d get to the pub first. ‘Nobody beats the Bomb!’ Martin shouted, as he leapt into his racing-green Riley sports car, pulled his goggles down and raced off down the narrow lanes, throwing the Bomb into blind corners at sixty miles an hour, Hugh’s headlights so close to his rear bumper that Martin kept thinking at any second Hugh’s Alvis would come crashing through the back window. On the hill down from Forty Green, the crazy fool had tried to overtake him! Their spoked wheels almost touching, it was all Martin could do to keep the Bomb from mounting the hedgerow.

At the Royal Standard, they’d laughed and told stupid jokes about girls, but mostly they had talked about cricket. At closing time, Martin invited everyone back to Whichert House, where they stayed up most of the night, drinking Irish whiskey until they passed out in the living room. As the birds began to sing, Martin climbed the stairs to the little, yellow-painted room in the eaves where he’d spent much of his childhood.

His eyelids are practically taped together. He squints at the framed painting on the opposite wall. A circus scene. A relic of childhood. During school holidays, he would lie here in bed counting the different animals. The tigers in their cage. The bear. The elephant on its chain. Now, his mouth feels like it has grown fur inside it during the night. His breath smells like a rotten cheese. He groans. Then he remembers. He has to get to the post before it closes.

‘Bugger!’ He leaps out of bed and throws on his clothes. ‘Bugger!’

Splashing cold water on his face, his eyes stare back at him from the mirror, like two piss-holes in the snow. He tries to smooth his tousled hair, to no avail, then races down the stairs, three steps at a time; grabs the parcel and rushes towards the front door. Scamp, Aunt D.’s Jack Russell, races after him, his claws scratching on the flagstones and barking at the slammed door.

Bright sunlight makes Martin’s eyes wince. It’s been crazy weather. Spring, the coldest on record; June, the rainiest; now, England is hotter than Spain. He grabs his bike and pedals down the drive, parcel in one hand, handlebars in the other, shoots out onto the Penn Road, spitting gravel and almost colliding with a furniture van. The driver blasts the horn, shakes his fist. Martin waves a cheeky apology, pedals on. It’s only a mile. If he hurries, he’ll make the post office before it closes.

On the high street, stockbrokers with bellies that hang down like aprons waddle along proudly beside large, pink-skinned women with piano-stool calves. Shop girls in pencil skirts sashay arm in arm towards the Wycombe End – cheeky, giggling, up for it, as boys in boots and braces catcall after them.

Martin throws the bike against a lamppost, sprints towards the entrance of the post office, put his shoulder to the door . . . and falls through empty air, across the floor. What he sees, when he looks up, seems a hallucination caused by a malfunction of the nervous system due to his overly enthusiastic intake of alcohol. A Fata Morgana. A phantom, dressed in a loose, blue and white cotton dress, cinched at the waist with a crocodile skin belt. Slender neck. A dusting of freckles. Kissable lips. Very kissable lips. What he notices most, though, in those brief seconds, is the cascade of chestnut-coloured hair tumbling over her shoulders. And those eyes. Clear, blue and full of hidden depths, like a cove he once swam in off Cornwall.

‘I’m so sorry!’ He struggles to his feet, clutching the parcel to his chest. Flicks his hair out of his eyes. Gawps.

‘I think that’s what’s called a dramatic entrance.’

Her voice is bright, musical. Like a bell, or a harp.

‘I didn’t want to miss . . . ’ His furred tongue tries to form the next word, twists about in his mouth, like a worm doused with petrol.

‘The post?’ She tilts her head to where the line snakes back from the window.

He flounders, tries to look tough, manly. Like the matinée idol, Douglas Fairbanks.

‘Well, if you hurry, you’ll still catch it.’ The girl pushes open the door and flounces out.

Martin stares after her, noting the sway of her hips inside the blue and white summer dress; the proud, haughty bearing. He wants to dash after her.

‘Martin? Dorothy Preston’s nephew?’ A diminutive, white-haired woman comes through the door.

‘Hallo.’ He opens the door for her, stares over her shoulder. ‘Mrs Heal, isn’t it?’

‘Yes. How’s your aunt?’

‘Fly-fishing in Scotland.’ He holds up the parcel. ‘Sorry. Got to get this off to her.’

‘Do give her our regards . . . ’

He joins the queue. Seconds turn into minutes. It’s one of the fixed laws of the universe. When you enter a post office, no matter where it is, in what country, time moves at a different speed. Post office time. He checks his watch. The queue shuffles forward. If he hurries, she might still be out on the street. One minute, two minutes, three minutes. His head is going to explode.

‘Parcel to Scotland, please.’ Martin drums on the counter with his fingertips.

The counter assistant takes the parcel and weighs it. ‘That’ll be one shilling and five pence, please.’

Martin pulls the money from his trouser pocket, pushes it under the window and runs out. The postmistress calls after him.

‘You’ve given me two pence too much!’

But Martin is already out on the street. He looks left, looks right, grabs his bike and pedals off, scanning the crowds for that blue and white dress. Vanished. At the top of London End, he turns around and cycles back towards the post office, mutters to himself. This is really stupid, you know. You nearly knocked her over! She’s not going to talk to you. Don’t make a fool of yourself.

He turns and begins to cycle slowly back towards Knotty Green. A gleam of chestnut hair. A blue and white dress. He whips round and pedals furiously back down the street, almost knocking over a small boy in a school blazer. She disappears cycling down an alleyway. Martin follows, at breakneck speed.

‘Hey! Watch where you’re going!’ A heavy-set man in a trilby shakes his stick in the air. ‘Bloody idiot!’

‘Sorry!’ Martin waves an apology, charges on between high brick walls. She is there now. Up ahead of him, just twenty yards away. A couple comes out of a jewellery shop. Martin swerves to avoid them, tips over, crashes into the opposite wall. The bike falls to the ground, wheels spinning. The couple snicker and walk on. Martin leaps back in the saddle, pedals furiously on.

‘Hallo again!’ he says, as he draws level with the girl. She stares through him. ‘The post office? I was the person . . . ’

‘Who almost knocked me unconscious?’ She pedals on.

‘I know. I’m so sorry, I . . . ’ Martin races after her. ‘Could I buy you a cup of tea?’

‘Not today.’ The girl increases her speed.

‘What’s your name?’ He draws level with her bicycle.

She eyes him warily.

‘I’m Martin. Martin Preston.’ He holds out his hand.

‘Pleased to meet you, Martin Preston.’ She increases her speed. ‘I’m Nancy.’

‘Have you got a surname?’

‘Everyone has a surname!’ She pedals off, with her beautiful, freckled nose in the air.

Martin starts to follow but is blocked by a lorry. When he looks again, she has disappeared.

Back at the house, Martin wanders around the garden, distracted. Scamp follows, sniffing, digging, peeing. The vegetable patch is bursting with fruit and vegetables. Martin stops by a tomato cane and pulls a fruit from the stalk. Raises it to his nose, smells it, then bites into it. The juice spurts into his mouth. ‘Nancy.’ He rolls the name around on his tongue, goes back into the house and picks up the phone, then dials his friend Hugh Saunders’ number.

‘Hugh? Yes. Martin.’ He pauses, unsure whether to proceed. ‘Look, I know this is going to sound ridiculous, but I just met this girl in the Old Town.’

‘Another one?’ Hugh chuckles.

‘Yes, another one.’ Martin laughs. ‘But this one, well, made quite an impression.’

‘That’s what you said about the last one, dear boy.’

‘I know.’ Martin laughs. ‘Thing is, Hugh, I didn’t get her name. Or at least, not her surname.’

‘So, what’s she called?’

‘Nancy.’ Martin sighs. ‘That’s all I know. Auburn hair. Blue eyes. Pretty. Very pretty.’

‘So how can I help?’ Hugh asks.

‘You know everyone around here . . . ’

‘I wish. But, sadly, I don’t know any Nancys.’

‘No?’

‘Sorry I can’t help.’

‘Oh, that’s all right. I’m just being foolish.’

‘Wouldn’t be the first time.’ Hugh chuckles. ‘How about a game of tennis to distract you?’

‘Tennis would be great.’

‘Tomorrow at eleven?’

‘Perfect.’ Martin puts down the receiver and stares out into the garden, thinking of the girl with the auburn hair.

That night, he dreams he’s back in Egypt, in the Khan el-Khalili souk, in Cairo, where his father was posted for many years as a high court judge. The air smells of spice and sweat. Crowds throng the narrow passageways. He’s jostled from side to side. Up ahead of him, he spots the girl from the post office, pushes his way through the crowds. He can see her chestnut hair up ahead of him. He starts to run. But his feet won’t move. It’s like running in quicksand.

Martin is an orphan of the Empire. His father, Arthur Sansome Preston, was a tall, flamboyant man with a long, angular face, silver moustache, and a taste for expensive clothes. He died a year ago. But even when he was alive, he was mostly absent from Martin’s life. Apart from trips together with his parents in the summer, usually to hotels in the Swiss Alps, they spent little time in each other’s company. His father’s life revolved around his work as a judge in Cairo, his racehorses, and the never-ending round of diplomatic parties. On the rare occasions they were together, they didn’t get along.

Since he was a schoolboy, Whichert House and Aunt Dorothy, his father’s sister-in-law and as unlike him in her warmth and cosy domesticity as it is possible to be, have been the fixed points of his childhood: the only place in the world he thinks of as ‘home’. Tucked away down a shady lane, with gable ends and brick chimneys, it’s a family house in the true meaning of the word, built around the turn of the century, by Aunt D.’s husband, Charles Preston, a successful lawyer with a practice in London.

Whichert – ‘white earth’ — is the name for the mixture of lime and straw used in the construction of the outer walls, a method unique to Buckinghamshire, which gives it the feeling of being, literally, part of the landscape. In the summer, the garden is a riot of flowers as bees drunk on pollen move among the blooms and the cries of ‘Roquet!’ mix with the clink of crystal goblets filled with champagne or Aunt D.’s legendary elderflower cordial.

Martin is roused from his dream by a scratching at the door. He opens his eyes, looks at his watch, then clambers out of bed, pulls on his shorts and shirt, slides his toes into the sandals then opens his bedroom door. Scamp hurls himself across the room. ‘No jumping, Scamp! Down!’

Still rubbing the sleep out of his eyes, Martin goes downstairs to the kitchen and fishes a stale loaf out of the bread bin in the pantry. He is home alone. Even Aunt D.’s termagant cook, Frances, is on holiday. He takes a knife and scrapes off a spot of blue mould, cuts a slice of bread, makes coffee. Black. Lots of sugar. Then he grills the bread on the Rayburn, slathers it with butter and Aunt D.’s home-made damson jam, then switches on the wireless.

The Foreign Minister, Lord Halifax, is talking about the Sudetenland. Chamberlain has just agreed to Hitler’s demand for a union with all regions in Czechoslovakia with more than a fifty per cent German population. But many people believe the crisis won’t end there. Martin listens attentively, then downs his coffee, fishes a packet of Senior Service cigarettes out of his shorts’ pocket, taps it with his finger, turns it upside down, peers into it, pulls a face.

‘Fancy a walk, old boy?’ Martin asks the dog.

Scamp races along beside the bicycle, his stubby legs working frantically to keep up. At the tobacconist, Martin buys three packs of cigarettes and the Sunday paper. He puts the paper in the basket on the front of the bicycle, unties the Jack Russell and prepares to get in the saddle. But the dog stops abruptly, spreads his back legs and squats. Martin drags him onto the street. ‘Good boy.’

A bicycle passes. Martin swivels. It’s the girl with the chestnut hair. Serene in the saddle as a paddling swan. Martin yanks Scamp’s leash, starts to run after her, but the dog is still doing his business. The girl smirks. Martin sets off in pursuit, dragging the long-suffering pooch along on his backside. Up ahead, he watches as she dismounts in front of a bookshop.

Martin sprints along the pavement and stops beside her, panting. ‘Hallo . . . ’

She turns round. Fixes him with those limpid, blue eyes. ‘Oh. It’s you.’

‘Che bella fortuna di coincidenza. What a wonderful—’

‘I know what it means.’ She looks back into the window of the bookshop.

‘It’s Petrarch.’

‘Really?’ Her voice is mocking, mischievous. ‘So you speak Italian, Martin Preston?’

She remembers his name! But he pulls his face back from the brink of a far too excited smile, points into the shop window. ‘Poetry? Or prose?’

‘Poetry.’ She starts to go inside the bookshop. ‘And prose.’

‘Do you like Robert Graves?’ His voice is almost pleading.

‘He’s one of our finest.’

‘He’s my uncle.’

Her eyes flicker with curiosity. ‘Do you write, too?’

‘Badly.’ He grins. ‘Mostly overdue essays. You?’

‘Notebooks full, I’m afraid.’ She laughs self-consciously and holds out her hand. ‘Nancy. Nancy Claire Whelan.’

‘Can I, er, buy you that cup of tea, Nancy Claire Whelan?’ he stammers.

She studies him for a moment. ‘I think I’d like that.’ She smiles. ‘The books can wait.’

They find a tearoom in the Old Town, packed with elderly matrons eating scones and cucumber sandwiches. Martin and Nancy install themselves at a table by the window, so Martin can keep an eye on Scamp, who he has tied up outside. They order a pot of tea.

‘Shall we have some scones as well?’

‘Tea is fine.’ Nancy unties her hair and lets it fall over her shoulders. Martin watches, mesmerized. ‘Thank you.’

A waitress in a black and white pinafore sets the tea on the table. Martin pours.

‘It’s so amazing . . . ’ He checks himself, tries to sound less jejune. ‘Meeting you like this. Again.’

Nancy takes some milk. ‘Was it a coincidence?’

‘Well, sort of.’ Martin blushes. ‘I suppose I was . . . looking for you.’

Nancy smiles. ‘How old are you?’

Martin is caught off-guard by her directness. ‘Nineteen,’ he says, flustered. ‘Almost twenty.’

Nancy sips her tea. He notices how she talks with her eyes almost as much as her lips. If she is amused, her eyes narrow, like a cat’s. Surprise is communicated by a subtle raising of her eyebrows. When she laughs, her eyes flicker with pleasure. Each mood, the tiniest oscillation of emotion, is registered in those eyes, an entire semaphore of signals and reactions, which he is learning to decode.

‘How old are . . . ?’ Martin checks himself. Never ask a woman her age.

She glances over the top of her cup. ‘Twenty-two.’

‘Do you live here?’

‘Yes. My father is a civil servant. Inland Revenue.’ She puts her cup down. ‘How about you?’

‘My father . . . ’ He hesitates. ‘Died.’ Through the window Martin sees a lorry full of soldiers. ‘Last year.’

‘I’m sorry.’ Nancy looks out of the window and registers the soldiers. ‘What about your mother?’

‘She lives in Wiltshire.’ Martin butters a scone. ‘In a nursing home.’

‘So what brings you here?’

‘My aunt lives in Knotty Green. I’m staying with her for a couple of weeks before term starts again.’ He looks across at her, proudly. ‘Oxford.’

‘What are you studying?’

‘Law and Modern Languages. Teddy Hall.’ He grins sheepishly. ‘A minor in partying.’

‘First year?’ Nancy smiles.

‘Second!’ Martin insists.

Nancy stares out of the window, with a dreamy expression on her face. ‘I used to live in Oxford.’

‘Where?’ Martin’s face lights up.

‘Cowley.’ She pulls a face. ‘Not exactly the dreaming spires.’ Pauses. ‘By the Morris factory, actually.’

‘That almost rhymes.’

‘What does?’

‘Factory. Actually.’

Nancy laughs. ‘It’s a very nice factory. Actually.’

They laugh together, eyes meeting, then withdrawing, touching again, withdrawing. Like shy molluscs.

‘Where in Knotty Green?’

‘Whichert House?’

‘That Arts and Crafts house? Opposite the Red Lion?’ Nancy’s voice is animated.

‘You know it?’

‘I cycle past it all the time. I love that house!’

‘It belongs to my uncle, Charles, and my aunt.’ He arches an eyebrow. ‘Dorothy Preston?’

‘That’s your aunt?’ Nancy reacts with surprise.

‘Yes. Do you know her?’

‘My mother does.’ Nancy pauses. ‘From church.’

‘Small world!’ Martin smiles at the coincidence. One more connecting thread linking them together.

Nancy lifts the teapot and refills their cups. Martin watches the golden liquid flow from the spout. Looks up into her eyes. Holds them. Like a magnet.

They meet at the same tearoom every day for the next week or go for long walks around Penn. They are creating a story together, a narrative of interconnected threads and confessions, and each meeting adds a new chapter to the story. In between their meetings, Martin mopes about like a lovesick spaniel. He can’t concentrate. The books he is meant to be reading for the new term are left unread. His face takes on a distant, faraway look, as though he’s been smoking opium. But he is under the influence of drug far more powerful than opium: a drug called love.

One day, they take the footpath towards Church Path Wood.

Conversation has progressed beyond the mere exchange of biographies. Today, they are on parents. His mother’s ill health and depression since the death of his father. Her mother’s asthma. His special affection for his sister, Roseen. And how his parents farmed them out to boarding school when they were living in Egypt.

‘That must have been so hard on you.’ She squeezes his hand.

‘Aunt D. was more like a mother than my real mother,’ he says as they stop at a kissing gate. Nancy steps inside, Martin leans against the wooden rail. ‘Sent me socks and marmalade. Posted my books when I forgot them. Spoiled me rotten in the hols.’

‘And your father?’

‘He was the black sheep of the family: “a bounder”, I suppose you’d say.’

‘Why?’ Nancy’s eyes widen.

‘Not sure.’ Martin chews on a grass stalk. ‘Gambling? Drink? Whatever it was, he was barred from joining the family law firm.’

‘Which is why he ended up in Egypt?’

‘That’s it. High court judge. President of the Jockey Club.’ Martin pauses. ‘My father basically preferred his racehorses to his children.’ He pulls an ironic grin, which can’t quite disguise the residual hurt.

One of the few things Martin’s father did teach him, ironically, was to hate snobbery. Colonial life in Egypt was driven by it: that insidious, British snobbery that judges people by where they grew up and the school they went to. One of the reasons Martin is so fond of Nancy is that she judges people for what they are, not their social rank.

She points across the field: a shimmering band of colour stretches across the eastern sky.

‘A rainbow!’ Martin says. ‘It must be a sign.’

She turns, and he’s there. Her lips and his. Sudden and electric. Their first kiss. The kind you get lost in. Like exploring a labyrinth in a blindfold. A labyrinth of feeling and touch and passion.

So that’s the story, Aunt D. I can’t wait for you to meet her. All’s well here. I just got back from taking Mother down to her new nursing home, in Wiltshire. She is still walking rather poorly after the fall, though when I hid her stick for a few minutes she found she could walk surprisingly well without it. The nursing home is really pleasant. Views of the Quantocks, a fire burning in the grate. A large, cheery lady named Mrs Dodds runs it.

How is Scotland? I hope you won’t get fly-fishing elbow again, even though you must keep up your fame as a fisherwoman.

Yours, Martin.

He lights a cigarette and sits staring out of the window into the garden. A soft, autumn rain is falling. Scamp lies sleeping by the fire. It’s only sixteen days since they met. But it feels like a lifetime. His world has been split in two, like a tree struck by lightning. There is before NC and after NC. Everything he sees, everything he tastes or touches or hears, he wants to share with her. When she is not there, his world feels bleak and empty.

Sixteen days. And everything has changed.