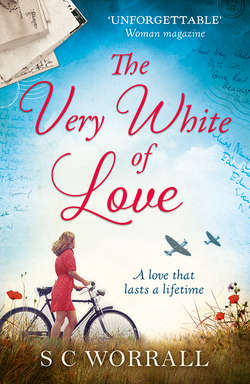

Читать книгу The Very White of Love: the heartbreaking love story that everyone is talking about! - S Worrall C - Страница 11

Оглавление14 OCTOBER 1938

Oxford

‘Forties, Cromarty, Forth.’ The shipping forecast crackles on the wireless. ‘Easterly or northeasterly 5 to 7, decreasing 4 at times . . . ’

Martin has fled his room at Teddy Hall to escape the drunken heartbreak of one of his friends, a hapless English student called James Montcrieff, who has broken up with his girlfriend. Martin offered him the sofa for a few nights. He’s been there two weeks. Drunk most of the time. So Martin has decamped to his friend Jon Fraser’s flat, in Wellington Square. Jon is a gangly second year student with a shock of red hair. Outside in the square, the last autumn leaves on the chestnut trees shine in the gaslight. Coals glow in the grate.

‘Could you turn that down, old man?’ Jon’s voice calls from the other side of the room. ‘I have to get this bloody essay finished by tomorrow afternoon.’

‘Sorry, Jon!’ Martin gets up and switches off the wireless. ‘How’s it going?’

‘Slowly.’ His friend leans back from his desk and stretches. ‘Have you ever read Valmouth?’

‘Is that the one about a group of centenarians in a health resort?’

Jon laughs. ‘Some of them are even older!’

Martin should be studying, too. Exams loom. But as Jon hunches back over his desk, he takes out her latest letter, lies down on the floor, his head cradled on a pillow, and lights a cigarette.

Dear Martin . . .

He has seen his name written by countless other people, on birthday cards or school reports; in letters from his mother; his sister Roseen or Aunt Dorothy. But seeing it written by her still makes his heart turn somersaults. The fluent, blue line of her cursive script is a river pulling him towards her. He already has a drawer full of her letters, each letter adding a chapter to the story they are creating. She has told him about her Dorset childhood and the books she loves; her favourite music; and her work in London; the places she dreams of seeing. No one has ever written to him like that. It’s not what she says; it’s how she says it. Her words ring off the page, as though she is right there, next to him, talking in that high, bright voice.

He gets up and pours a glass of vermouth, lights a fresh cigarette, takes out a sheet of writing paper embossed with the college’s coat of arms: a red cross surrounded by four Cornish choughs. Then lies back down on his stomach, smoothing the sheet down on the back of a coffee-stained copy of Illustrated London News. The cover photo shows German troops marching into the Sudetenland two weeks ago.

The talk at meals is all of war. But tonight he has only one thing on his mind. Unscrewing the top of his pen, he holds the gold nib in mid-air, searching for the right words. A ring of blue smoke hovers around his head, like a halo. He lays the burning cigarette in an ashtray, breathes in, then puts pen to paper.

Dearest Nancy,

I’m writing this on the floor of Jon’s little room in No. 11, Wellington Square. My own room has gradually become its old self of two years ago – a meeting place for many. My cigarettes disappear; the level of my vermouth drops and the table is covered with other people’s books. What I need is a hostess, a beautiful aide-de-salon.

He tells her what he’s been doing since their last tryst: hockey matches and motor cross trials; auditions for a play; parties he has been to; a film by a new director called Alfred Hitchcock; the latest college gossip. If only he had the eloquence of his famous uncle. But she’s stuck with him. He takes a drag of his cigarette, chucks back the vermouth.

I don’t know how to feel when you’re around. You turn me so inside out – no one has ever done it before. What is it about you? You are unparalleled. You leave me breathless. You are the most exciting thing in the world. I’m a little ashamed of writing what I needn’t mention really but occasionally my heart overflows with drops of ink for a letter to you. And I must write before the term begins in earnest. It is like offering up a prayer before going into battle. Though my prayer to you is only that you will understand how much I love you. When you are around, everything feels right. Your love is like a crown. If I could be with you right now I would frighten you with my passion. I can’t say more – you must feel it.

In the distance, the clock of St Giles strikes midnight. A group of drunken students pass under the window, shouting and laughing.

It’s terribly late now. I’ve wearied my right hand writing letters about hockey matches and things like that. Jon is writing furiously at his desk about ‘Ronald Firbank’. Not the actor. He has to deliver the essay tomorrow evening. Oxford is depressingly cold. Everyone else seems hearty and too pleased to be back here. Poor things, they can’t have anyone to make their homecoming so desirable. I suppose we shall have the usual – muddy games, the usual tiresome duties, and work which one must settle to and then enjoy.

It’s strange and wonderful to know you so perfectly. I imagine myself with you the whole time. Feel your lips against mine. My hand touching yours. I can’t wait to see you again next weekend.

So very much in love and kisses in adoration, Martin.