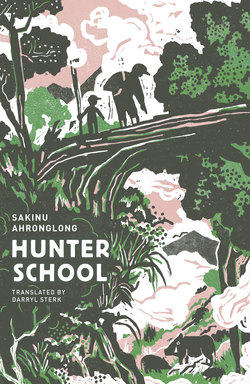

Читать книгу Hunter School - Sakinu Ahronglong - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

Ever since I was a boy, I’ve seen my Paiwan tribespeople inundated by society, carried away in the flood. Growing up, I witnessed members of my tribe getting eaten away by reality, even swallowed whole. Reality’s pursuit is relentless, while tradition has receded from us, leaving us helpless and indecisive, leaving wounds in our hearts – in our innermost worlds. The reality is that our villages have been invaded by foreign culture, which has fragmented the tribal social structure and deprived us of the totemic tattoos that adorned the bodies of our ancestors. Without the tattoos, many of us try to pass as Han Chinese. Unable to recognize us, our ancestral spirits have not been able to give us their blessings or offer us comfort.

I have dedicated my life to the reconstruction of traditional Paiwan culture, to show the ancestors that we know who we are. We may not tattoo our bodies, but we can consolidate our village communities, speak our language, and follow our own way of life.

I have faced a lot of opposition. In my mind, I can hear my father, a devout Christian, cursing me when I announced that my wife and I were going to get married in a traditional wedding ceremony. But even when my father called me Satan for reconstructing the culture of our tribe, I did not waver. Never have I wavered since I made my choice. I have never complained nor regretted a thing.

For I am Paiwan! This is an unalterable fact. The beauty of Paiwan culture attracts me profoundly. In fact, it has become my faith and my identity.

There are moments of clarity in everyone’s life, and for me the moment of greatest clarity came when I stood on the top of the Ta-she Mountain in Pingtung County, south-western Taiwan and looked down at the old tribal village in the valley.

In that moment, I finally realized what it means to be Paiwan! I perceived the Paiwan-ness in our traditional slate houses and in our stunning totemic carvings of the hundred pacer snake. My tears gently fell. I stood there all emotional for the longest time. It was as if I were an orphan boy finally learning his parentage.

In the tribal village where I grew up, it was once hard to find traces of traditional Paiwan culture because of the severity of Sinification.

Everything Paiwan was a distant blur for me, until I met my mentors – the Paiwan sculptors Sakuliu and Vatsuku. From them I learned many precious things. From Sakuliu I learned the practicality of a Paiwan person’s wisdom, while Vatsuku shared with me the Paiwan manual creativity.

Sakuliu and Vatsuku initiated me into Paiwan culture, but I would never have been receptive to it if it weren’t for my father and my grandfather.

My father hasn’t always supported my decision, but it was in observing him and his father that I first saw beauty in the traditional relationship with nature. When I was a child, nature was my classroom. Everything in the mountains was my textbook. My grandfather was the headmaster of the school, my father the teacher. It is there that I learned the wisdom of my tribe, passed down from generation to generation.

I’m still celebrating my luck in having an amazingly wise grandfather and a hunter for a father. In my father, I saw the principle of coexistence between man and animal. In my grandfather, I realized the truth of coexistence of man and nature, the truth of sharing and mutual benefit.

One day, Grandpa said, “I’m old. There are not many days left for me to see the sun rise and set. The millet in my field is now ripening for the very last time. My legs no longer have the strength to kiss the land I know so well, nor my fingers the force to pull the trigger of my hunting gun. I am old. I’m old.

“Last night I had that dream again,” he said. “The ancestral spirits were calling me, asking me to go with them. I asked them to give me a bit more time and let me tell all the stories I have to tell, before my life ends. In these eighty years I’ve lived, I’ve lived enough. But before I leave, I want to pass on the glory and dignity of the past to the next generation.

“The words that I’ve uttered, you must record with pen and paper.” Grandpa’s helpless eyes, which had borne witness to the ravages of time, and the wrinkles on his face, which was inscribed with the runes of history, obliged me to comply with his request. Before he passed away, I had to transcribe his wisdom in a book for everyone to read, hopefully to understand. The hard part was that I had to do it in my own words.

“I’m dumb,” I told an editor to whom I had shown an essay. “I haven’t read much, and the things I write nobody reads. I can’t write essays like the other people.”

“Sakinu, why would you want to be like anyone else?” she said. “Everything in you is literature, things other people don’t have and can’t imitate. Sakinu, let everyone know all the things you keep hidden, let your life story, and Paiwan history, come flowing out of your pen.” That was a revelation. I thought it over. I should be proud because I’m indigenous – I’m Paiwan! Now I am proud to tell everyone my only faith is Paiwan, from beginning to end, never to change.

In the past six years I’ve written a lot of things. My objective at the beginning was to make an account of what had happened to me, what I had realized, and what I had heard of the oral accounts of the village elders and their life histories. I wanted to tell the next generation how we once lived in this space.

I dedicate this book, such as it is, to my mentors, my father and grandfather, to the next generation, and to the beautiful woman by my side who has supported me the most, my beloved wife A-chen. A Siraya princess from Tainan County, she has chosen to make a life with me in New Fragrant Or-chid, Lalaoran in Paiwan, between sea and sky on the southeast coast.

Which is where, if you will allow me, I will guide you in this book.

Sakinu Ahronglong