Читать книгу Hunter School - Sakinu Ahronglong - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTranslator’s Note

“My name is Paiwan!” Sakinu proudly declares. “This is a fact that will not change!” But what does it mean to be Paiwan? Sakinu speaks an Austronesian language that is now called Paiwanese, but it is unclear exactly what paiwan itself means. It might have been a village name – it might have been the name of a plant. It has only become the name of a language in modern times. According to the “Out of Taiwan” hypothesis, Taiwan is the original homeland of the Austronesian language family, meaning that Paiwanese as it is spoken today shares a common ancestor with Polynesian languages and Indonesian, not to mention Tagalog, Malay, Hawaiian, and Maori. Austronesian is a cultural category, too, and Paiwan practices like headhunting and millet cultivation spread from Taiwan through the Austronesian sphere thousands of years ago.

In pre-modern times, Paiwanese was linguistically and culturally unstandardized and therefore highly variable from village to village. In modern times, Japanese scholars from 1895 to 1945 and Chinese and Taiwanese scholars since 1945 have studied the Paiwan and their language. Their studies are written representations of the Paiwanese language and Paiwan culture. These written representations have, in turn, become the basis for written standards. There are now written standards for different dialects of Paiwanese, which are used in teaching materials designed to save the language. Sadly, Paiwanese is now only spoken by people of Sakinu’s age – he was born in 1972 – or older. It really is a mother tongue, and it will soon be a grandmother tongue if attempts to rejuvenate it are not successful.

In supporting the compilation and use of these teaching materials, the Taiwanese government is trying to undo decades of efforts to suppress the language and the culture. Taiwan was officially Chinese until martial law was lifted in 1987, and has only belatedly embraced multiculturalism, particularly with regard to ethnic minorities like the Paiwan who were once called savages. Taiwan has recognized peoples like the Paiwan as indigenous since the mid-1990s based on a simple principle: they were living on the island of Taiwan for thousands of years before the ethnically Han Chinese settlers arrived in southwestern Taiwan in the seventeenth century, and they remain distinct. Official recognition of indigenous peoples is just one of the reasons why Taiwan is now one of the most progressive places in East Asia. Today, Taiwan is the East Asian country that has tried to do the most to make its original residents feel at home in their own homeland.

Sakinu feels at home in his village in southeastern Taiwan and is playing a role he has cast himself for. That role is to be a cultural ambassador for the Paiwan people, where “culture” can be understood in two ways, as identity and as adaptation. As an identity, Sakinu’s culture is distinct practices, including the festivals his village holds and the styles of clothes he wears. To some extent, Sakinu understands these practices according to standards based on research by Japanese and Chinese scholars, but he also understands them based on his own village community experience and oral history research. As you will notice as you read, Sakinu has a very strong sense of local identity, of being a Paqaluqalu – east coast Paiwan – from Lalaoran, a village with its own distinctive practices.

As an adaptation, Sakinu’s culture is an approach to survival in premodern times, when if you wanted dinner you had to hunt it or grow it yourself. Is hunting your own meat and growing your own millet still adaptive when you can now drive to the supermarket and get everything you need? Sakinu thinks so. He thinks that there’s something missing in the modern or postmodern lifestyle, which has alienated many of us from nature and stranded us in screen-based media. That’s why, in 2006, in his mid-thirties, a half a dozen years after publishing the Mandarin edition of the collection you hold in your hands, Sakinu founded the Hunter School. You can understand the Hunter School in terms of ethnic or eco-tourism, but if you talk to Sakinu you’d realize how sincere he is about helping young people reconnect with their original home, which remains the source of anything they could buy in the store or see on the Internet. Tragically, the Hunter School burned down in May, 2019, but then the school is a state of mind, and will, I am sure, get rebuilt.

I first met Sakinu in the summer of 2010 when a friend of mine, Professor Terry Russell, and I were doing some research on how indigenous writers write about the topic of home in their works. We wanted to interview Sakinu because in a way he doesn’t do anything but write about his home. We were very grateful to him for showing us the Hunter School, introducing us to his father, who as a construction worker has visited more countries than Terry and I had combined, and for showing us his millet field and hunting ground. This visit helped me imagine the places in Sakinu’s stories as I was reading and translating them. It’s an honour for me to finally give Sakinu a gift in return by translating his stories.

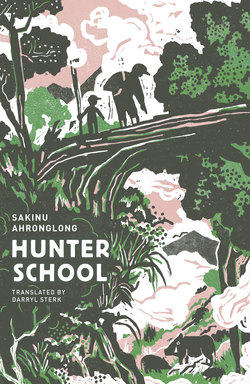

This collection was published as Shanzhu, Feishu, Sakinu in Mandarin. As you can tell, the three words in the title rhyme. Sakinu rhymes with shanzhu, meaning “mountain boar”, and feishu meaning “flying squirrel”. As you can also tell, the English title wouldn’t rhyme.

I considered calling the collection The Sage Hunter, the title of a 2005 feature film based on Sakinu’s stories. But in the end, I went with Hunter School, in honour of the actual school that Sakinu built and will rebuild.

I’ve reordered the stories in the collection to tell the story of Sakinu’s life and the lives of his fellow villagers: from an idyllic childhood to an adolescence in which Paiwan people get buffeted by socioeconomic forces beyond their control, to a maturity in which they are finally able to reorient themselves and choose their own path.

Sakinu’s path is a hunter’s path. As someone who as a child used to read The Call of the Wild by the light of the moon, I wanted to follow Sakinu down this path, only to discover that to Sakinu it’s not the call of the wild, it’s the call of his Paiwan ancestors. To Sakinu, there is nothing wild about a Paiwan hunter, who is every bit as civilized as you and me, if not more so. In these stories, Sakinu translates the call of his Paiwan ancestors into terms that modern Mandarin readers can understand, and I’ve done my best to relay-translate that call into English.

Darryl Sterk