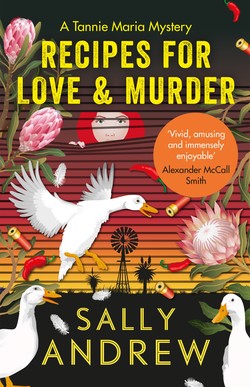

Читать книгу Recipes for Love and Murder - Sally Andrew - Страница 20

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER FIFTEEN

‘Mevrou van Harten? It’s Detective Lieutenant Henk Kannemeyer. Can I come round now?’

I looked at the clock on the wall. It was noon.

‘Could you make it at one o’clock, Detective?’

He cleared his throat. Everyone in Ladismith knows business is not done between one and two. All the shops close so that people can go home for lunch. Except for the Spar. And the police station.

‘I can give you a bite to eat,’ I said. ‘That is, unless . . . ’

Maybe he was expected at home.

‘It’s okay,’ he said. ‘I’ve got sandwiches.’

‘No, no, I’ve made roast lamb.’

‘Roast lamb?’

‘With potatoes and pumpkin. Soetpampoen.’

‘Oh. Well then . . . ’

I wondered who made him his sandwiches.

I put the cake in the oven and took the foil off the lamb. Then I prepared the chocolate icing. I added the rum and buttermilk and tasted the dark mixture on the tip of my little finger.

‘Mmmm,’ I said. I added a pinch of salt and then tasted again. ‘Perfect.’

I cleaned the kitchen and laid the outside table. The big jug of lemonade with ice and fresh mint stood next to a tray with the letters from Martine, and her friend, Anna. My replies were there too.

The heat had melted the dark blue out of the sky, leaving it that pale Karoo blue. But the trees and tin afdak kept the stoep cool.

I took off my apron, tidied my hair and put on fresh lipstick. I heard a car heading my way and I smoothed my dress and went outside. A bokmakierie was calling to its mate in the thorn tree. I saw his police van pulling up in my driveway. Those birds make such a beautiful trilling sound, it goes right through your heart. I walked up the pathway to wave at him. Just so he knew he was in the right place.

I watched him get out. Long trousers and his khaki cotton shirt a bit open at his neck and chest. He touched the tip of his moustache and dipped his head as he greeted me.

‘Just listen to those bokmakieries,’ I said.

‘Ja. Lovely.’

We walked to the stoep together. He sat down, fitting his long legs under the table.

‘Smells good,’ he said.

‘Lemonade?’ I poured some into a tall glass for him. He smelled good too. Like sandalwood and honey. ‘Here are the letters I told you about. I’ll just be in the kitchen.’

He started reading as I went to look after the roast and the chocolate cake. The cake needed to cool before I could ice it.

When I came out with the roast lamb and vegetables, Kannemeyer was holding the letters in his hand, and looking out across the veld at our red mountain, the Rooiberg. I could still hear the bokmakieries calling, but they sounded further away now, maybe in the big gwarrie tree.

He jumped up to help me put the roasting tray on the table.

‘Shall I carve that for you?’ he said.

I handed him the knife.

‘I’ll get the handwriting checked,’ he said, slicing the lamb, ‘but I think you’re right – these were written by Mevrou van Schalkwyk and Mejuffrou Pretorius.’ He shook his head. ‘Those white ducks . . . ’

‘You read my letters too?’ I said, spooning potatoes and pampoen onto his plate.

‘Ja. I read them all.’

‘So you can see why I feel involved. Responsible, even,’ I said, dishing the green beans.

He frowned.

‘If I hadn’t told her to leave, he wouldn’t have killed her,’ I said.

‘You can’t blame yourself, Mrs van Harten.’

‘If I had told her about people, organisations, that could help her, keep her safe,’ I said, putting some of the best lamb slices on his plate, ‘she could be alive today. Like me. About to eat a nice lunch.’

The thought that she would never eat lunch again made me very sad.

‘Tannie Maria,’ he said, ‘we don’t even know it was the husband. It might have been suicide. Maybe it was Anna. We don’t know yet. You can’t blame yourself.’

‘It wasn’t suicide. And you don’t really think Anna— ’

But I didn’t want to ruin the meal with an argument.

‘Let’s eat,’ I said. ‘Help yourself to gravy.’

The food was perfect. The lamb was dark and crispy on the outside and tender on the inside; the potatoes, golden brown; the pampoen sticky and sweet. Kannemeyer closed his eyes when he ate his first mouthful. We did not talk while we ate. I could hear the bokmakieries again, out in the veld.

When he’d finished eating he said: ‘I haven’t had such a lekker roast since— For a long time.’

A little bit of gravy was on the tip of his chestnut moustache. He smiled. That lovely white smile again. But his eyes looked sad. He wiped his mouth with his napkin. It was time to set things straight, while the food was still warm in his belly.

‘Detective Kannemeyer,’ I said, ‘you know it was her husband who killed her.’

‘Maybe. Maybe not. You need evidence to convict someone.’

‘You’ve read the letters,’ I said. ‘I was there when this . . . man tried to kill Anna in the police station.’

‘Ja, Anna must lay charges against him. But that is a separate matter.’

‘Have you got evidence that someone else could have killed Martine?’

‘We are waiting on . . . reports.’

‘What reports?’

I was wondering about Anna’s fingerprints and the autopsy.

‘Ma’am,’ he said, ‘Mrs van Harten. We are handling it, you don’t need to worry.’

‘But, Detective, we do worry. The man can’t just get away with it. We could help you investigate the case.’

‘We?’ he said, glancing at the watch on his thick wrist.

‘Well, us, at the Klein Karoo Gazette,’ I said. ‘We’ve got an investigative reporter, we know people in the town. We could find evidence . . .’

‘Mrs van Harten,’ he said, standing up. ‘I appreciate the information you have given me, but this is a murder investigation for the police to handle.’

‘There’s cake,’ I said. ‘Buttermilk chocolate cake. With rum in the icing.’

‘Sorry. I have to go.’

The bokmakieries had gone quiet now; from far away on the R62 came the sound of a truck driving up towards Oudtshoorn.