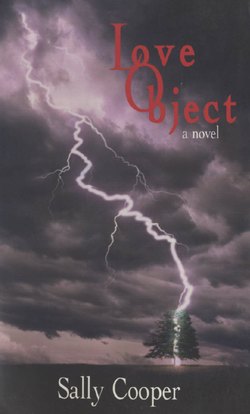

Читать книгу Love Object - Sally Cooper - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1 You Are Somewhere

ОглавлениеMy Uncle Larry Brewer has meek snores: a mew followed by a sigh or a gasp, nothing like the riotous carols I’m used to hearing from my father Sam or from Grandma Vi. The effort of straining to catch Larry’s snores is what wakes me up inside those first two dreams of Mother.

It’s the Saturday of Canada Day weekend, July 2, 1983, and Larry’s down to help Sam insulate the addition before returning up north to Drag County to wait for his next job. Our place in Apple Ford is one of Larry’s stopovers on the Sudbury-Windsor route he’s been running four times a year since my mother Sylvia left in 1978. He parks his rig at the arena and snort-laughs when Nicky and I beg to sleep there. Vi has just moved in with us but she makes a point of staying at a friend’s after she sees Larry and Sam playing euchre at the kitchen table with Nicky and me.

When he plays euchre, Larry says he likes to imagine a real court, an upside-down court where the knaves, the jacks, the everyday guys have authority over the king. In most games the jack is the lowest face card but not euchre. In the euchre court, Larry points out, the queen is down near the bottom where she belongs. The order of the game appeals to Larry, the reversal of fortunes that comes when he least expects. He relishes the terminology too. Trump. Trick. Bower, which comes from the German bauer, meaning peasant or knave.

“Euchre is about the triumph of the KNAY-vuh” Larry says, drawling out the word as if he is afraid he sounds too smart. “I’m a perfect example. A jack-of-all-trades. I’ve driven bus, sharpened saws, cut hair, laid pipe, chopped trees, cleaned ditches, plowed snow.” Hauling steel is the most gainfully employed Larry has ever been.

Vi says, “As far as I’m concerned a jack is a scoundrel. Just look up knave in the dictionary, Mercy,” she says and I do and she is right.

“Not just scoundrel” I read, “but rogue and rascal too.”

Larry flutters his eyelids then squints and talks in a flat Clint Eastwood voice until Vi leaves pulling her suitcase across the plywood floor of the addition.

Sam plays cards with indifference but we know better; Sam has memorized every possible combination of cards in a given game. He can quote Hoyle and he lays cards without looking at his hand. To add flair, he has devised several precise gestures and difficult manoeuvres: shuffling the deck away from his body, using one hand to deal, turning up cards with the flick of a finger. He wins every game then acts as if he has no idea why he bothered to play in the first place. The romance: of the court and the beauty of inverted power delineation do nothing for Sam. To him, cards are a math problem and he plays with the confidence of one who understands the true nature of numbers and can manipulate them to lie for him and only him. A notion that each deal might bring something new and never been before is what causes his brother Larry to lose most times he plays. This same sense of mystery is also what spurs Larry to play again and again.

Saturday I wake up before my alarm with the sheets wound in knots around my legs. My skin, sticky with sweat, holds a pickled brine smell. Sylvia’s crocheted afghan lies in a heap on the floor. Before doing anything else, I pick up the afghan and straighten it on the bed, Sylvia’s instructions still ringing clear after five years. I’m less than a month away from my seventeenth birthday but I still have the same little girl’s room Sylvia did up for me as a grade-six graduation gift: the white ruffled curtains, bed skirt and pillow shams, the blue fleur-de-lis wallpaper, the oval hooked rug with cardinal and jays on a leafy branch, the furniture painted white with gilt trim. True, posters of David Bowie in his suit and fedora do hang next to Sylvia’s framed 3-D collages of hummingbirds and finches and Stephen King has joined Lewis Carroll and the Brothers Grimm, but the rest is the same as it was before Sylvia left.

With a lamp on, I stand in front of the round dresser mirror that cuts me off at the shoulders. I am proud of my body this summer. Last summer, filing claim adjustment forms for Sam’s insurance office, I gained ten pounds from sitting all day dipping into a bag of Licorice Allsorts in my desk. This summer I cycle to and from the Trout Club and spend my evenings in the back yard painting planks for the addition’s board-and-batten siding. My legs and arms reflect my efforts. A hard muscle curves out on the back of each thigh and my arm pops a bulge when I flex.

My summer job is bussing tables and washing dishes at the Tecumseth Trout Club, an exclusive resort for fishermen. Members stay in the main lodge, coming for a weekend or a week.

The Club backs onto the Tecumseth River and sits away from the road, protected from local eyes by thick bunchy cedar. The Tecumseth River courses down from the escarpment and through the Trout Club ponds, swings around Apple Ford, then hustles back west to hie itself across a golf course and head south. In April the province dumps trout into the river and fishermen with rubber boots stretching over their trunks cluster along the road and railway bridges that cross the Tecumseth east, west, north and south of Apple Ford. The Trout Club stocks its man-made ponds at the same time.

The Trout Club kitchen has three deep sinks, for soap, bleach and rinse, banked on each side with grooved porcelain counters. If I leave early enough, I will be first at the sinks — before Duncan Matheson, my drying partner, arrives for the morning shift. I pull on shorts, tank top and sweatshirt, slip into my moccasins and catch my hair in a red plastic headband. At the Club, I will change into the requisite gabardine A-line skirt and white blouse.

Larry’s plaintive murmurs drift up from the pullout sofa, Sam’s joyous croaks chiming in from his summer bed on the front porch. I keep to the edge of the stairs to silence the creak, my ear cocked after each step for any variation in the snores’ timbre and pitch but I hear none. I tiptoe through the living room though I needn’t bother. Larry lies in a fetal clench with a rust velour seat cushion, the blankets low enough on his hips to reveal pale blue boxers under his white T-shirt. In the kitchen, my head hits Sylvia’s macramé lampshade as I reach across the table to snatch my K-way from a chair. I tuck a strawberry Pop-Tart into my pouch and enter the addition. The room, with its newly dug cinder-block basement and west-facing window, is cool and smells of sawdust. Pillows of pink fibreglass insulation in white plastic bags are stacked against the far wall studs. A neat pile of dust, scrap wood and nails sits in the middle. Sam’s tool belt hangs over a rod in the closet. I cross the plywood floor, open the new red door and jump onto the clumpy dirt. The sky is shifting from grey to pink.

The addition is Sam’s idea, announced to Nicky and me as a family project at Christmas. With Vi here it makes some sense but in two years Nicky and I will likely be off to university or college and Sam won’t need more space.

“Makes for a better house. More proportionate,” Sam says to silence anyone who asks.

What is more important is that Nicky and I help so that we’ll learn how and because the house is ours too or might someday be. Nicky pitched in from the beginning, his bent neck patterned with knotted jute shadows as he and Sam pored over the blueprints. Sam accepted each excuse I gave when he suggested tasks, but once the walls went up he got adamant so I’ve agreed to paint the boards he is using to cover the outside. Painting is easy and I can do it away from interference — or so I thought.

Last Saturday, Sam and Nicky took the Dodge to pick up the planks from a lumberyard and piled them under an orange plastic tarp beside the small barn we call the garage. When I came home from the Trout Club, Sam showed me the paint and a red milk crate full of supplies. I waited until my next day off while Sam was at work before I wrestled the sawhorses out behind the garage where Sylvia’s vegetable garden used to be and laid a long board across them. I flipped the milk crate on top of spread newspapers for a table. I placed a brush, a coffee can full of Varsol, some rags, a screwdriver, a hammer and a stir stick in a semicircle around the open paint can, stood back to admire the arrangement, then got to work.

The boards took longer than I thought and I got to counting the strokes and measuring the paint, saturating the brush to make each dip last. I propped each plank against the garage wall when I finished one side.

I wiped at my brow with my forearm, careful to hold the paintbrush away from my body. A slow blue drop lengthened from the tip of the brush. Before it could detach and aim for my bare leg, I flicked my wrist and flung the paint onto the grass.

An ache developed between my shoulder blades as I bent over the sawhorses and stroked the sopping brush up and down. Some paint bubbled but the grain absorbed almost all. I plunged the brush back into the can, wiping the drips on the rim. Blue splashed on the crisp brown grass.

When Sam’s hand dropped on my shoulder I jerked the brush toward myself and a splotch hit my thigh. I hadn’t heard the truck. I dipped a rag in Varsol and scrubbed a burn into my skin as the paint dissolved.

Sam bent and plucked a blue hank of lawn. The top of his head gleamed a burnished kidney. He’d combed pomade through what was left of his wavy hair and it shone. Around his jean shorts he’d slung his cowhide belt, heavy with tools.

“Your brush is too wet and your paint is sloppy.”

“What’s the big deal? They’re painted and they look fine.”

“They don’t look fine. We’ll see brush marks and drips and the knots need to be treated so sap doesn’t bleed through. I should have showed you. It’s my own fault.”

I tossed the rag onto the newspapers. Watery blue liquid spread across the print.

“Your set-up is sloppy too. Don’t just use the coffee cans for thinner; pour the paint in, one-third full. Then you can press the brush against the side to remove the excess, instead of against the brim of the can and spilling everywhere. But before that, you should sand each board and treat the knots. This isn’t easy.”

I didn’t want him to say what he was going to say next.

“If you do something right the first time, you won’t have to do it again. And besides,” he added by way of a joke, “my way, you’ll get more paint on the boards than yourself.”

I’ve only worked one evening since then and my production speed was considerably slower. I followed Sam’s every instruction to the letter — shaking then stirring the paint until it had the consistency of heavy sweet cream, adding citronella to make it bugproof, gluing a paper plate to the bottom of the can — before I remembered that I was supposed to prep the wood. I sanded the surface and shellacked the blemishes and knots of one board then had time to apply only one coat before it got too dark. Sam didn’t say anything about quantity or the quality of the job so I took it I had done okay.

A thick morning mist coats the back of the yard and goose bumps rise on my legs. Long grass shot through with purple-whiskered thistles crowds the edges of the lawn. Split-rail fencing and four maple trees separate our property from a hilly field to the north. Beyond that are farmhouses, ranch bungalows and some mansions. Apple orchards and more fields. Our closest neighbours are middle-aged couples like the childless Fat and Terese Palmer, who have the town’s only functioning outhouse, and Kipper and Shirl McDonald, none of whose five kids, including the one who is a former convicted pyromaniac, lives at home.

What would Sylvia think of the addition? Is an extra room enough? Would Sylvia recognize our green-shingled house sheathed with blue board-and-batten?

The dreams of Mother catch in my throat. Without swallowing, I stride across the yard to where a narrow path cuts through the long grass. I stamp to provoke the grasshoppers into the scattershot flight I love but they cling in torpor to the swaying blades and my moccasins end up drenched in dew.

I skirt around Fat Palmer’s outhouse through an empty lot then down the dirt hill that leads into Middle Street. Apple Ford has five streets: Front, Middle and Back run north-south while Victoria and Elizabeth go east-west. Front, Middle and Back have official names but nobody uses them and there are no signs.

Above a rise of lilacs on my right, a fence sags. Beyond that lies a shorn field, its hay gathered into rolls that loom in the vapour. There is only the clap of my feet in the quiet of no cars. I walk by blank-windowed red-brick houses until I reach the culvert over old Mrs. Brant’s stream. The water flows from a pipe I remember not from the times I drank as a child when shortcutting between Front and Middle Street but from kneeling on the sodden grass after leaving Rick’s that first night, when I mashed my lips against the cold lead and water shot over the ends of my hair, down my neck, into my blouse. I haven’t drunk here since, but this morning I’m not coming for the pipe.

I hop off the culvert to the far side of the path and walk across ground mushy under dead leaves and needles to a maple as tall as the one outside my bedroom window. I press my belly against its trunk and stretch, my fingertips straining to stroke the tip of the seam I can’t see. This scar from a lightning-severed branch is as mine as if I wear it on my own skin. With the dreams of Mother skittering over me I need even a moment of my hands on this old electric wound. As I charge the dreams, fixing them clear in my mind, I hear the urgent ring of the railroad-crossing signal south on Front Street. I lean harder into the bark, wishing to be crouched on the embankment beside the tracks when the train passes, its sweating oil movement shaking through me, embracing me in calm.

With a jolt, I let my arms fall free and head back down Mrs. Brant’s driveway and north on Front Street to home. I don’t linger or even look at Rick’s storefront when I go by. In the three months since I saw Rick last I haven’t passed this way once. Though he often works until four in the morning, by now Rick will have crawled into his loft bed and fallen asleep. I’ve never been up there with him, in his bed. I’ve never seen him sleep and don’t know if he likes to lie on his stomach or his back or to clasp a pillow in a curl like Larry or if he snores and if so, what kind. I have only even seen him with his eyes closed once and he was standing up awake that time.

I trot past the church and the manse and up the hill to our place where I grab my bike from the garage. Yesterday’s skirt and blouse are stuffed in a grocery bag on the rear wheel rack. I put my right foot on the pedal and push, then swing my left leg over. I am pumping before I hit asphalt. My neck aches, my throat is raw and my ears plugged at the damp cold on the first hill. By the time I reach the Ford Road it’s like sailing with the rosy-gold sun on the back of my head, but it isn’t enough. The dreams swarm over me and I let them.

1

I am on a train in a compartment with six others who are speaking French. I try out my voice. Softly, to myself, when the others are asleep. The commotion of machinery is loud but consistent. If I could find its rhythm, I might sleep. I do not fit the seat, and pain stabs my shoulders. The man beside me speaks another language than French, maybe German. He has made it clear he wants nothing to do with me.

2

Mid-morning. By myself. Blue seats. A new train. The backsides of factories pass, breaking up long stretches of yellow-green fields. The leaves are polished browns, not the thrusting reds and oranges of home. I am in France. Mother sits five rows ahead. From the beginning Mother has refused to sit beside me. The possibility of her arm jostling mine or her bare knee grazing my unshaven one disturbs her, arousing Mother to the point of fear. I watch the back of Mother’s head, content.

The cook is the only one in the main lodge before me. I turn on the hot tap, swishing the water around each stainless-steel sink. I like to hold the spout so the water hits the side of the basin and spreads into one flat stream. At this hour, the water takes at least five minutes to come out hot so I let it run, and squat to get bleach, J-Cloths and SOS pads from the cupboard under the sink. I have my own set of yellow rubber gloves with M.B. written inside the cuffs in black magic marker.

When the water is steaming, I plug the centre drain and add three capfuls of Javex.

My body vibrates as if I have just stepped off a train. The Mother in my dream preoccupies me. That Mother is odd, nothing like Sylvia, but she is mine. My heartbeat is relentless in my ears, neck, chest. The dreams fill me with a strange happiness, maybe because they are set in France. French is my favourite and best subject in school. My last teacher gave slide shows on Fridays, serving croissants and cocoa. I feel closer to Sylvia than ever before.

When the middle sink is full, I swing the tap over the third sink and fill it with plain water. Then I turn on the cold. When I am able to hold my hand in the water, I squirt a circle of Sunlight into the first sink and fill it.

Sam writes messages to Sylvia on lined paper torn from pocket notepads bought at filling stations. He leaves these notes wherever they occur to him: his work table, the toaster oven, his dashboard. Every so often he collects the scraps in a handful and stuffs them into a Black Cat cigar box on his dresser.

Sam’s messages to his wife turn up between lists of chores and sundries jotted down in spidery capital letters:

CLEAN OUT EAVESTROUGH

3 BAG MILK

YOU ARE MINE SWEETHEART

CARTON EGGS

SIGN REPORT CARDS

26 RYE

MON — FILL TANK GAS ($13)

STAPLER BACK TO WORK

YOU ARE SOMEWHERE. I AM

SEARCHING. WHEREVER YOU ARE.

SHARPEN KNIVES

MINUTES LAST CLUB MEET

CLEAN GOOD SHOES

LET ME CALL YOU BABY. I’M THE ONE

FOR YOU. WAITING.

ROTO-TILL

After nearly five years with Sylvia gone, Sam’s box is full of these absent-minded notes. I found them years ago and read them often, savouring the odd lines to my mother:

I WILL MAKE YOU MINE WHEN YOU

RETURN TO ME LOVE.

YOU ARE THE MOST AND DON’T I

KNOW IT.

HANG IN THERE DARLIN I’M RIGHT

HERE YOURS.

They are like Hallmark cards but not as poetic though Sam’s words do hold a sombre hopefulness more appropriate to true love. I read these lines as if they were written to me, as if I am the one who left a lover yearning in our empty bedroom. I’ve believed that when I am a lover, the desperation and utter faith behind these lines will be my right. After Rick, I am no longer so sure.

This evidence of Sam’s unfaltering belief in my mother’s return comforts me. I’ve never thought about my parents loving each other. They’ve been apart since I was twelve and I’ve spent more time thinking about my mother’s love for me than her love for my father. That Sam’s love is obvious is good. I sit cross-legged on his pine bedroom floor, my toes falling asleep under the weight of my knees, my head dizzy from bending my neck, and let myself trust in the Sylvia of my father’s urgent lines, a Sylvia certain she is loved but busy with important work.

For long moments, I can forget my body and believe in a distracted and vital Sylvia who writes intense, soothing, unsent replies to Sam. That Sylvia is on her way home.

Then the truth hits again, seething through me like acid released by a dam. Sam is wrong. Lovers are supposed to be together and if Sylvia reciprocated his love she would have made her way to him by now. It is easier to believe the romance: Sylvia in the clutches of another more possessive lover, unable to return to where she is loved the most. Sylvia is crazy; she could have wandered off and been picked up on the road by dangerous people.

I keep a folded newspaper clipping behind my bulletin board:

SAN FRANCISCO —Kidnapper caught. Linda Smith, 15, was kidnapped after a Nasty Matters concert Feb.12 at the Filmore East. Smith claims the kidnapper used cigarettes and candle wax, among other things, to torture her. “We went for drives and walks all the time but I was too scared to escape. When he went into the washroom at a Texaco I knew I had to run.” Mark Weiss of Palo Alto will appear in court Tuesday.

Sylvia could be with a man like that, or a husband and wife, or even a biker gang. Maybe she is too crazy to get away.

My mother’s clothes still hang in her closet; Sam has never remarried or even dated. Sylvia must have made a life away from her husband and children. A life important enough to run to. I tuck in my chin at the thought. Maybe that other life is my mother’s due but I can’t help but feel I deserve it too.

The only dishes at this time of morning are coffee cups and dessert plates stained with strawberry juice and dried cream. I put my gloves on and drop each dish into the soap sink.

In her new life my mother could be speeding around France on a moped, eyes goggled, hair and neck swathed in chiffon, a dusky Grace Kelly. Anything is possible. What is also possible, if Sylvia has escaped, if she is alive and free to choose, is that she might return to Apple Ford. Sam is ready, Nicky too. Me, I’m not so sure.