Читать книгу Love Object - Sally Cooper - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

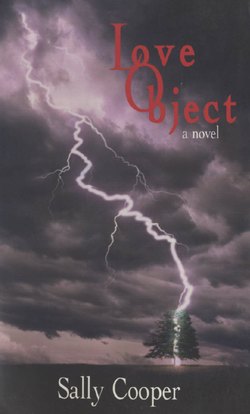

3 Storms

ОглавлениеThe last week of June, the week after school let out, was a week of thunderstorms. In the beginning the rain came first, the lightning stretching across the sky then snaking in on itself. By the end of the week, the clouds were stopped up, the water brewing inside, their countenances so dark, I imagined they contained more than water: bits of fur and roadkill; cat paws, raccoon tails, rabbit teeth, even whole groundhogs; birds’ legs and beaks; human fingernails, earlobes, wrists and kneecaps; fragments of half-digested carrion: proof of the consuming powers of the storm, or perhaps the ingredients of the malice forthcoming. The brawling clouds had powers, I believed — the yellow veins of electricity and the ear-splitting cracks evidence of some great rage waiting to be spat out at the unsuspecting and the unprepared.

The mornings descended like a wall. At first daylight, I awoke in a frustrated panic, sheets tangled, old sweat collecting around my hairline, dreams of sirens lingering: ambulance, police, fire, all mingled together.

I lined up Mason jars behind the garage. Each day I unscrewed another lid to collect that day’s rain. Each day I discovered the clouds brooded longer, and each day the water level was substantially higher — even though, as the week wore on, the rain fell with more and more force, splashing out of the jars and catching on the surrounding grass.

At the first low rumble, my forearms prickled. I kept time records and loudness records in the orange pocket notepads Sam brought home from gas stations. In the early evening’s hush after the storm subsided, I walked around Apple Ford, assessing the damage, looking for ugliness, for evidence of that great wrath: fragments of bone and animal ears and bits of cloth, tangible proof that the storm’s fury was real I sought out trees struck by lightning and cut the wood free with Sam’s hunting knife, smuggled out of the house because of its forbidden sharpness. I laid my hands on the shining burnt crevices where the limbs had been severed. Energy, perhaps electrical, perhaps more than that, surged into my hands and maybe into my veins. At home, I stored the bits of lightning wood in a box in my bedroom closet, checking them with the lights out to see if they glowed. Underneath, I was driven, certain as I was of my own flesh that something magical was to be gained from this knowledge, this accumulation, this seeing. I stayed quiet and paid attention. If I waited long enough, the secret of the storms’ temper would be my own.

Now that we were home from school, Sylvia sat in our kitchen all day and smoked. Her hair was limp with hurnidity but her stretchy headband matched her blouse. She stared at the yard, green now, the grass long and unmanageable. Mowing it was Sylvia’s job, but she no longer went outside and Sam wasn’t home long enough. Sylvia stacked her butts in a hefty black and green ceramic ashtray. I emptied it before Sam came home. The summer before, Sylvia had smoked a little, one or two a day, and usually only in the evenings if Sam was there. She had worn lipstick then, painted her lips a solid flat red that left filmy kiss marks on the cigarette. Sometimes she’d handed a butt to me, lighted, and let me smoke it. She got out her compact to show me the smear of red that remained on my lips and I walked around pushing my lips out, wishing for someone to kiss. This summer, Sylvia wasn’t wearing lipstick, her lips paler than her skin. This summer she was smoking the butts down until the white part was no longer visible. The kitchen was hazy with smoke and Nicky pretended to have choking fits whenever he came in.

Sometimes Sylvia spoke, her voice hoarse now, her words garbled. I winced, pretending to ignore it. Sylvia’s voice used to be the first thing I heard when I got in from school, calling from the kitchen and asking how my day had gone. She would beam when she saw me, hand me a plate of Ritz crackers spread with peanut butter and granny apple slices with a few drops of lemon squeezed on them so they wouldn’t brown, and sit down, eyebrows raised. I would pour everything into my mother who would smile and nod, seemingly overjoyed at her daughter’s very existence. Now I had my doubts.

I had to pass through the kitchen to get from my bedroom to outside. I ran in and out, grabbing Mason jars from the top of the basement stairs, rummaging around in the junk drawer for labels, glue and magic markers. I tried to be fast; keeping records was messy business. It didn’t fit any known rules. But the rules were starting to give, their seams weakened. There were ways of slipping through that went unnoticed.

The house with its dull brown rooms and green linoleum floors existed as a container for me, an endless source of supplies. I moved through it as I moved through the compartments of my night dreams, slowly but with purpose, sliding around the edges, wary of disturbing anyone.

On the third day, the rain caught me out in the carrots and weeds behind the garage, causing the round pen lines of my notes and charts to bleed into each other. That night by my window, greedily absorbing each breath of breeze that rustled the maple leaves, I traced the ridge marks my Bic pen had made on the pages underneath. Since I couldn’t copy the figures correctly, the tone was set for the next day’s collections. As the storms wore on, my figures became more and more fabulous; one day the water level was a foot high, the next it was three. I had no way to tell for sure.

The day after getting caught in the rain, I slipped into the kitchen to look through the drawers for a Baggie to carry my notebook in. I stood with my head cowed, my body angled away from Sylvia.

It didn’t work.

“Come here, Mercy.”

Sylvia’s monotone voice had a weary quality that threatened to swallow me. I shuddered.

“I said over here. In front of me. Where I can see you.”

I stood my ground.

“I’m in a hurry.” I almost called Sylvia “Mommy” but this name didn’t seem right anymore. I didn’t want to stay, but leaving would make me somehow responsible for her sitting by the window smoking.

Sylvia’s eyes moved. They lit on me for a second then flitted up to the cupboard where they rested.

“I want that hair cut. Come here.”

I pushed the drawer shut with the heel of my hand. The drawer was loose and jammed partway. I moved over to the table, standing out of habit to Sylvia’s left.

She raked her fingers through the tangles. She hadn’t combed my hair into ponytails for months and now my thick hair hung in snarls.

It felt good to have my hair pulled. I liked to have my mother’s hands in my hair, near my scalp. The pulls made my scalp tingle. I leaned into my mother. Sylvia tugged harder and the familiar sharp smell arose. I tilted my nose up. I liked to hold the hair to my nostrils and inhale. When it was wet I sucked on the ends. I hadn’t washed it since before the storms, when I’d skidded a bar of soap over my head and dunked it under the tub water. I glanced at my mother. The corners of her eyes looked pinched.

With ragged nails, Sylvia tugged and twisted, the pulls getting keener.

I breathed through my mouth, my eyes on her taut aqua headband. Sylvia moved her long hands down. She tweaked my collar, brushed my shoulders, licked a finger and rubbed my knee. Her eyes stayed fixed on the floor beyond my feet. I pressed even closer, my side against Sylvia’s, my knees against her thighs.

I stared at her, willing her to return the gaze. The hair tucked under Sylvia’s headband lay in lank, oily clumps, the ends resting on her collar. Her wrists were so skinny the bones dug out of her skin. Her smell was one of smoke and underarms and hair — much like my own, only with a sourness I couldn’t place. She no longer baked, read magazines, made clothes or talked on the phone. She didn’t go to pottery or rug hooking, had abandoned knotting macramé and crafting driftwood. She just sat in her chair, knees and elbows crossed, and smoked. There were no more rules for knowing her. Even broken rules didn’t alert her.

Sylvia grabbed a handful of hair and jerked it back.

“It should be off your face.” Her voice was low and clear. Her breath smelled like a dirty dishrag and I turned my head away.

Sylvia yanked harder. I forgot all about staying out of trouble.

“It’s my hair!” I yelled. “If you can keep your hair like that, I can do what I want with mine.”

Sylvia rose out of her seat, her head veiled by swirls of sunlit smoke, and cracked her hand across my jaw.

In that moment my mind formatted a new type of mother touch. Sylvia hadn’t touched me in I didn’t know how long. It was a trap: Sylvia’s fingers in my hair, Sylvia letting me lean up against her, luring me. My mother’s hands, the ones that used to be large safe places for me to hide my own fearful hands, now sprouted mean fingers out to destroy me. This mother made no sense. My mother’s palm against my cheek broke the rules. The ringing slap had set me free. There were no rules now for loving Sylvia. I shook, unable to open my eyes.

Sylvia sat back down and waved her long fingers.

“Leave me alone.”

Her hand fell back to her lap. She put a cigarette in her mouth and didn’t bother to light it.

I backed out of the room. Sounds of whimpers and sniffing followed me. I quickened my step and went straight to the bathroom where I stared in the mirror at the welt that had been Sylvia’s hand. I hoped it would stay, a badge I could wear before the world to prove something was wrong with my mother, and that I, Mercy Brewer, stood victorious in the face of it. Already though, the mark was fading.

I wanted to tell Nicky but he wasn’t around. He wouldn’t believe it. Even if he did, he wouldn’t see it as a sign that Sylvia was different now. I didn’t know why. All I knew was that the very sight of me disturbed Sylvia now, as if she was thinking about something important and couldn’t be interrupted. Whenever I managed to catch her eyes, they were deserted. I was used to looking at my mother and seeing a gleaming, perfect, well-loved version of myself shine back. Now it seemed as if nothing of me was left in my mother’s eyes and that scared me. If my mother couldn’t see me, who could? I would almost rather have the witch-mother who sat outside our bedrooms with her glowing red eyes. At least that mother cared about what we were thinking, even if it was only to prove we were thinking bad thoughts about her. This mother, the one in the kitchen with the mean hands, was worse than any witch I could imagine. I vowed to study Sylvia and see how much she had changed. Maybe it wasn’t even her sitting in the kitchen, the sunbeams crisscrossing her hair. Maybe she’d been transported or her soul had died but her body lived. Whatever it was, I wanted to stay as far away as possible. On the fifth day of storms I started up the closet game. The sight of Nicky’s hair capped over his brown neck as he bent over a stack of Lego blocks spurred me to action.

I entered the room on the balls of my feet, resisting the urge to dance. Behind my back I held his slingshot. For Nicky the temptation of an item taken away before he had thought to use it was too much, particularly if that item was a weapon.

I leapt in front of him and his head snapped up. I dangled the elastic of the slingshot before his eyes, holding it just out of reach as I would for a cat.

Nicky forgot about the Lego.

“Give me that. It’s mine.”

He made clumsy grabs at my wrists, stumbling to his feet. His ears reddened and his grabs turned into slaps.

He repeated himself: “You don’t need that. Give it to me.”

To taunt him further I wrinkled my forehead without smiling. I didn’t say a word.

Nicky attempted a few short kicks. I danced into the hallway, the slingshot high above my head, Nicky jumping and smacking my arms and back. With one foot, I neatly flipped open the closet door and tossed the slingshot into the darkness. Nicky scrambled after it. I kicked his feet in and slammed the door, dropping the hook snugly into the eye.

We were used to this game. Usually Nicky stood close to the door, taking light breaths that I couldn’t hear, until guilt or curiosity overcame me and I unhooked the lock. Then Nicky would bolt past me beneath my arm, glad to be small and hard and fast. I was fast too so he didn’t waste any time.

This week was different. The heat in the open air was unbearable enough. Inside the closet Nicky might feel like he was suffocating. I’d hidden in my own adjacent closet to escape Larry Jr. on his visits and I remembered the sweat. It stung my open eyes. I’d sniffed it into my nostrils and tasted it on the corners of my mouth. It poured down my cheeks and dripped from my chin. The back walls of our closets had removable boards that led into a crawlspace blanketed by fuzzy slabs of pink insulation. Nicky and I had ventured in there together once but he’d backed out right away, fearful of the pink blocks turning into parasites and attaching themselves to him. He said that if so much as a finger touched the pink insulation, our whole bodies would itch for weeks, maybe months.

Nicky gave in.

“Let me out!” he yelled, pounding the door.

In the hall, I stood back, unsmiling, my eyes on the doorknob, ready to spring for safety or seize Nicky at the slightest indication the catch wouldn’t hold.

“Lemme out. Lemme out. Lemme out.”

His voice got higher and quieter, almost singsong.

I pretended I wasn’t there, willing my ears to concentrate on the whir of a lawnmower next door. I considered tiptoeing down the stairs then sneaking back. Or just staying away. I had never gone that far. He might die if I did that. I was about to dare myself when a wail came from the closet, followed by a roar. My ears tingled. Maybe I should let him out. As I reached for the doorknob, I heard a thud. The shrill noise continued, sounding like a wheeze or a nasal guffaw.

I hit the door.

“Stop laughing, you idiot. I know it’s fake.”

Inside I wasn’t so sure. Where was my mom? Nicky’s laughing was loud. Usually Sylvia interrupted any loud games, telling us to pipe down.

Regular thumps began. I rested my palms on the clock wallpaper, my breath coming in pants. I knew exactly where my mom was: in the kitchen smoking or more likely, asleep on the couch.

I quietly lifted the hook and was halfway to the stairs when both the keening and thumping stopped. I listened for a few moments longer then stole back. When Nicky was through playing dead and rattled the doorknob, he would burst into the hall and I could stand with my arms crossed and say, “What’s your problem? It wasn’t even locked.”

I hung back, smirk in place, shaking from my shoulders down. Outside the lawnmower stopped; the air was motionless. From the closet came silence.

Maybe he really was dead. I curled my hand around the doorknob, ready to attack if need be. If he were dead, I’d be mad.

When I opened the door a few inches, Nicky flopped into the hall, arms raised over his head, armpits stained with sweat, his weight flipping the door all the way open. It swung back against Nicky’s shoulder. His eyes had rolled back so I could only see the whites and the pink line of his inner eyelid. A froth lined his lips. It was white and frilled with yellow and purple and smelled curdled, like Pablum.

I refused to believe it. Wishing something couldn’t make it come true. Besides, I hadn’t really wished it. Not deep down. I wanted only to see what would happen. I pushed at Nicky’s knee with my toes.

“Get up, Nicky. Stop faking.”

No response. I willed his eyes to open. Fear clutched my shoulder blades.

A few seconds later, Nicky’s eyes did open. He gazed straight up at me with hatred and non-recognition. Then he closed his eyes and his body twitched. The twitches turned to shudders and soon his legs and arms were thrashing against the walls of the narrow hallway. A thin stream of liquid spilled from the corner of his mouth and his head thumped against the floor. I screamed and ran downstairs. It didn’t matter any more about my mother. By locking Nicky into the closet I had made him a monster.

Sylvia was in the kitchen.

“Mama, there’s something wrong with Nicky, he’s on the floor hitting the wall. With his head. He’s out of control.” It was hard to get the words out for sobs. “I didn’t mean to do anything,” I said after a minute.

Sylvia’s face seemed to click back into focus. She dropped her cigarette and charged out of the room, her legs taking impossibly long strides. I was right behind her.

When we got to the top of the stairs, Nicky was sitting up straight, his hands on his knees.

Sylvia lurched down beside him, folding him in long arms like prehistoric bird wings.

“He’s okay, right?” I said, standing back at the top of the stairs.

She sat back and held Nicky’s face in both hands. “Get a cloth!” she yelled, not taking her eyes off Nicky’s.

I grabbed a facecloth and held it under lukewarm water, then wrung it out. Sylvia reached her hand out and I dropped the cloth into it. She swiped Nicky’s mouth a few times. Using the corner of the cloth, she patted the foam off his lips and dabbed at his shirt.

Nicky croaked. Slowly he recognized me. He didn’t seem to notice Sylvia.

“What?” he said.

“Did you call emergency? You have to call the volunteer fire department out here. The ambulance is too far,” Sylvia said, clutching Nicky to her chest again.

“Not yet,” I said. “I didn’t think he was sick. It just happened.” I didn’t say I’d thought he was faking. It was wrong not to tell what had happened but it sounded stupid to say it; I was a horrible person for making him play the closet game.

“Don’t bother calling anyone. He looks fine now.” Sylvia rocked Nicky, her movements solid, her grip tight.

“But you didn’t see him. He was rolling on the floor. He was out of control.”

“What happened? Why was he doing that? Was it a game?” Sylvia’s smile was the kind that made me feel like I had no idea what I was talking about. I doubted what I’d seen and felt worse for having caused it. If something was wrong with Nicky, we wouldn’t know because Sylvia didn’t think he needed to go to the hospital. My chest got all hard as if I’d swallowed a big piece of meat. I had put Nicky’s life in danger. Then I’d laughed at him. What was wrong with me that I could do such things to my brother? I’d locked him in the closet because I thought it was fun. It was fun when he didn’t get sick. In the dim hallway my mother’s eyes were vacant hollows boring into me with full knowledge of my games, of my evil ways, and the scary thing was that those eyes didn’t care one bit.

Nicky blinked as if he was coming out of a long, much-needed afternoon nap. Later he said he remembered nothing about the closet and was conscious only of a light bruise on the crown of his head. Nothing similar ever happened to him again. He shook his head and seemed surprised to be in our mother’s arms. His eyes held a hatred so clean I could mistake it for love. Nothing I did would taint it; he could survive anything.

Sylvia released him. He sat back against the closet door, mouth closed. Sylvia stood up, arms trembling.

“I don’t know what to do with you two,” she said. “You are wild. I wouldn’t be shocked if you killed each other one day, if you don’t kill me first.” She walked past me and went back downstairs.

I couldn’t look at Nicky or even speak. But I didn’t want to leave him. What if he had another fit? Then for sure I would call the fire department even if Sylvia told me not to. I would run down the street myself and pull the alarm. Nobody would get in the way now of me protecting my brother even though I was as aware as he was that the opportunity to protect him was over. He had grown past me and was strong in a way I had never expected, a way that magnified my own weakness: my meanness.

I asked him if he wanted to sit in the garage loft to watch the storm. The sky was near black so it was time.

Nicky didn’t resist. Normally he avoided the storms, huddling in his room with his Lego bricks or a stack of comic books while the sky cracked open. Now, as low rumbles came across the fields, Nicky jumped up as if he craved the storm. I craved it too. Nothing was more important now than to be outside with Nicky, our faces against the air while the storm whirled around us.

On the final day of the thunderstorms, I woke early, my skin cool. Outside was silent. I got up and moved as if through heavy air, my hands relying on the walls and furniture edges, all of my senses cottoned up. I walked down the stairs, fingertips on the clock wallpaper, instinctively stepping as close to the inside as possible to avoid creaks. At the bottom I paused, my hand on the newel post, and listened to my father’s snores warble through the half-open bedroom door. I checked the living room couch out of habit and was glad to see Sylvia not there. A few more steps, through the kitchen and the mud room, and I was in the back yard.

Outside, I folded myself into a chaise longue under the pear tree, the morning heat already enough to warm me, and gazed past the house. The slightest curve of sun was rising. Behind a pink film of clouds peered the concrete sky I’d grown used to all week, but the sun was there now and that was all I needed to know.

I fell asleep and dreamed and woke with my mouth hanging open, a clear stream of drool joining my lip to my red nightie. I was unsure where I was.

The chaise longue creaked as I got up, and an earwig skittered across the canvas. I walked through the long grass in the back yard and down the hill into the town in the sunshine, past all the familiar houses, cutting through the fallen branches along Mrs. Brant’s stream, over the tracks, past Hoppy’s Wrecking Yard and across the road to the ballpark. The park was full of activity: a fair with livestock and rides by the river and a baseball tournament. Sam was playing and so was Sylvia, who stood in right field wearing an oversized catcher’s mitt. I wanted to be in the game but I couldn’t make myself go over.

Instead, I headed toward the Stevens’ house. Their front door was open, so I entered, passing through Mrs. Stevens’ dining room with its rows of plates along the tops of the walls, into the long, skinny kitchen and out through the back yard where the Stevens were having a family party. They glanced up without acknowledging me. I continued until their voices and the umpire’s shouts and the Ferris wheel music had faded into a low insect hum and I was in the grass alone. The field grass was much shorter now. It gleamed deep emerald. All sound disappeared. I heard only a roar like the inner folds of a conch shell pressed to my ear.

When I looked up, I was in a graveyard. I could see no houses or people in any direction, even though the Stevens’ house wasn’t that far behind me and the river was somewhere up ahead.

I looked around again. The field had filled with intricate bushes: lilacs, wild rose, sumac, honeysuckle, peony — and wilder things too: nettles, thistles, milkweed, golden rod, burdock. The field invited me to explore, to crawl between the branches on the dirt and grass floor. The bushes parted and receded as I made my way between the slim gravestones, many of which had upheaved themselves, exposing raw earth. The ground was spongy, lumpy. Water seeped into the edges of my footprints. The gravestones wore such mottled faces that even when I wet my fingers and rubbed the surface of the engraved letters I couldn’t read the names of the buried. A secret wanted to reveal itself but no matter how deeply I went into the graveyard, I was unable to expose it.

I squatted and discovered pieces of blue and green glass and washed white china, the edges rubbed smooth as though by water. I folded my fingers over them, their sleekness calming me, flowing into my body. I had never heard of this cemetery before: to the best of my knowledge, Apple Ford had no burial sites for its citizens. I must have been the only one who knew about it. I couldn’t believe I hadn’t noticed a graveyard before.

Seconds later I was awake, really awake in the chaise longue, my skin gummy. I knew now what to do with the lightning wood. I would fashion a man from it and when the storms were over I would walk through town, find the graveyard and bury him there. This man would be my charm against Sylvia. Only his burial would protect me.

It happened in the kitchen the day after the storms broke, the sky a blue so bright it ached to look at it.

I woke to the crunch of gravel. Through the maple leaves outside my window, I saw the corner of the green Impala as Sam turned south out of the driveway. The house was silent. Outside was a cacophony: birds, squirrels, shrieks of children, cars, chainsaws, lawnmowers, hoses. It wouldn’t thunder that day. Sylvia was sitting in the kitchen. I could tell it in my bones. I could almost smell the smoke sidling under my door, coming for me.

The storms had been a buffer against Sylvia all week. Now the skies were clear and there was nothing to protect me from my mother’s rawness. Sylvia’s presence, the force of her will, urged me to come downstairs to see for myself that all was clear, that the storms had made my mother fine if only I would see for myself. If I went down though it wouldn’t be alright; it would be worse than ever. There was nothing I could say to my mother. The words sank into me, building on the mountain of hurt. The more Sylvia tried to make things look alright, the more obvious it became that they weren’t.

Instead I sat on my bed. Sylvia no longer cared when I woke up — or if she even saw me all day. I’d swiped Sam’s Swiss Army knife and I whittled and shaped the wood I’d collected with the spear blade and nail file. I glued white circles with numbers inside them on the sides, the brown mucilage coming from a bottle with a red rubber top. The end result would be a man. It would be big and it would have some charm. If I worked hard and fast enough, it might alter what was fermenting downstairs.

By the time the sky had darkened down to navy and June bugs were battering my screens, I was only half-finished, if that. The smell of burning meat, barbecue sauce and charcoal briquettes drifted in and made my stomach growl. I cut the numbers faster, no longer varying the sizes, just getting the job done. My fingers were gummed and I had to peel glue off my skin with my fingernails. Wood shavings and scraps of paper stuck in the holes of my afghan. I’d added pale yellow cocoon husks and praying mantis carcasses and maple keys and a Centennial penny flattened by the steam train. An old Latin textbook of Sam’s formed the base.

Downstairs a door slammed. I heard Nicky’s familiar stomp. Sylvia’s voice rose sharply: “Where have you been?”

I picked at the crust of glue on the red rubber bottle top.

Sylvia spoke again, her voice quavering: “You can’t just do what you want to. You have rules.”

Something metal crashed and Sylvia pleaded: “Nicky, why can’t you be nice? Why don’t you say something? Answer me. Please answer me.”

I picked up the scissors and nipped at the skin around my fingernails. Lately I hadn’t heard much more than a guttural command from my mother.

Sylvia’s pleas continued, picking up momentum, slicing through the thick, smoky evening air and pressing my fingers to move faster, the glue clotting on my skin.

“You’re such a good-looking boy. You could make yourself look so good. I bet girls really like you. You have my dark hair and skin. You’re going to be a beautiful man someday.”

I imagined Sylvia drawing Nicky to her, twining her fingers through his hair, the way she did when she used to comb mine in the mornings. Nicky’s hair was smooth with no knots to catch her fingers. My hair was frizzy and light brown, my skin pale. How strange to have a brother more beautiful than you. I strained to hear Nicky’s voice, but Sylvia’s loud singsong blotted everything out. Nicky must be standing still, leaning into her, lulled. She would pull his hair enough to make his scalp feel good. Nicky could never see what was really going on.

Then Nicky exploded.

“Fucking bitch!” he screeched, his voice higher than a girl’s.

His feet thudded through the living room and down the hall. He ran up the stairs two at a time, hurling swear words behind him.

Goddamnbitchbastrdfuckincuntl He screamed it like a single word, like the words he and I made up and said as fast as we could so no one would know we were swearing. I bent the glue cap back and wedged the scissor tip inside the slit. I pushed it around making the hole bigger and bigger until the cap gaped open.

Nicky slammed past my room, kicking my door a few times before stomping into his own room. Once there he was quiet, but downstairs Sylvia’s voice was still going, the same up-and-down pleading and insisting and demanding and probing. She wasn’t loud anymore; I could no longer understand any words. It was eerie. She continued as if she wasn’t alone, as if Nicky’s outburst had never happened and he stood, head bowed, in front of her as she combed his hair.

Soon the ranting ceased and Sylvia called us for dinner. Her voice was sweet, inviting.

“Hurry up,” she added. “We’re having barbecue. Your father is finishing up the hot dogs.”

I put my paper, scissors, glue and wood back into the box and opened my door. Nicky stood outside, his cheeks flushed and his eyebrows forked over his nose. I couldn’t condone his kicking my door and wasn’t ready to be friends yet, so I shrugged and pushed past him into the bathroom.

He was close behind. He brushed my arm as he stretched his grime-streaked hands under the running water. Usually when we touched it was by accident and it was a contest to see who would be the first to recoil and brush away the germs. This contact was no accident. I didn’t move away. Nicky squeezed closer and we stayed that way for a long time, leaning over the sink, hands under the hot tap that always ran lukewarm. We used our thumbs to rub away glue and dirt, but when we were done we kept our hands under the water, to feel its warmth on our skin, to listen to it rumble up through the pipes and splash out of the tap over our hands and down the drain. Right then, standing arm to arm and washing hands was the best thing in the world.

Soon, the hot water kicked in; I yelped and jumped back. Nicky’s forehead was smooth and brown and he looked small. I reached past him to turn off the tap then sat on the side of the bathtub to wait. I didn’t want to look at him anymore so I inspected my fingers, rubbing and peeling off the remaining glue.

“I’m not even hungry,” Nicky said, his hand on the doorknob. He wanted me to laugh.

I met his eyes. “Why did you have to call her a bitch?” It was words like bitch that made my mom act strange. It scared me that my mom did whatever she could to make people say the words she hated so much. If she could make even Nicky say those words — Nicky who never got mad, Nicky who let me do anything I wanted to him — then maybe she was strange all on her own. But Nicky had yelled at her and I too had yelled at her three days ago. Nicky and I must just be bad. But Nicky was worse. He swore.

Nicky put his hands on his stomach and seemed to pull himself inward. He bit his bottom lip and his ears reddened.

“That just shows what you know,” he said. “You’re the one I should call the bitch!”

He looked ready to spit. He opened the door, pushed his fist hard against my shoulder and clomped down the stairs. It wasn’t even a punch, and it certainly didn’t hurt, but the meaning was there. I stood limp, aware of the throbbing shoulder but unwilling to feel anything. I listened for the commotion I was sure Nicky would arouse downstairs but it didn’t come. The longer I heard nothing, the weirder it seemed.

The only light on in the kitchen was the one above the stove. Nicky sat at the table, his lips pinched white, a dirty triangle of burnt meat on a plate in front of him. The table was bare, without tablecloth, place mats, serviettes. There were no hot dogs, no barbecue. Our father was nowhere to be seen.

Sylvia stood at the stove, a cigarette dangling from her lips. She wore lipstick spread in thick uneven streaks. It was a ghastly colour, like brown bruised plums.

“I thought you said we were having hot dogs,” I said.

Sylvia didn’t answer. She clutched a variety of kitchen tools: a spatula, a straining spoon, a ladle, some wooden spoons and a bread knife. She banged them on the stove, against the frying pan that held three more blackened chops amid globs of white grease, on the stove overhang, on her own wrists.

Her eyes were like pennies — lighter, coppery, but flat and turned inside, not out.

“Sit down, Mercy,” Nicky hissed. His hands clutched the edge of his seat, his eyes never leaving Sylvia.

“Yes, dear. Sit down. Let’s have a nice family dinner.”

Sylvia let the utensils fall as though she’d forgotten them and lifted a chop from the frying pan using the fingertips of both hands. She dropped the meat on the table in front of my seat. She waited there, posed, foot, ankle, knee, thigh, hip all turned out perfectly, like a housewife in a magazine ad for Crisco or Betty Crocker. Her hair was still oily but she had teased it back into place. It resembled the empty carapace of a beetle, wings slightly outstretched, poised for potential motion. Her eyes clouded over, giving her away. Around them hung shadowy sacs of skin, making her face look both bloated and drained.

“I won’t sit. Nicky was right. No. Maybe he wasn’t right. He said you were a bitch. I say—”

I couldn’t finish the sentence. I’d said bitchl And not by accident. I was as bad as Nicky. Worse! I knew better. Those words made my mom act funny and here I was saying them. But I couldn’t take them back. What little was left of my mom, the part that wanted a nice family dinner, was receding from those sunken eyes. What could I do to bring her back? Getting angry wouldn’t help. I ducked my head and slid into my seat, trying not to gag as I picked up my fork and knife and sawed at the chop.

“I’m not finished with you, young lady,” Sylvia said, her words congealed with tears. Still, I detected the steel underneath.

“I’m sorry.”

“This is not good enough. I wish your father were here to see this. Darn it.” Sylvia ground the heels of her hands into her cheekbones.

Nicky and I cut into the meat, pushing the blunted edges of our knives against the bone to sever the charred flesh. Maybe if we ate the way she wanted she would be happy. I glanced at Nicky but he just glared into his meat.

Eating didn’t work. Sylvia sniffed in hard. She whirled around to the stove, seized a wooden spoon and brandished it like a sword, eventually turning it on herself, beating it against her bony forearms. Nicky slid off his seat and crouched under the table. I raised a piece of burnt pork to my lips. Sylvia ran from the room. She slammed two doors, one after the other, and wailed.

The portion of meat perched on the end of my fork was black on the outside, inside a pinkish grey. I hated meat, always had. I would sit at the table through Sam and Sylvia’s dinner conversations, chewing on a single piece until my jaw felt like thick rubber bands and ached when I tried to separate my teeth. Given the chance, I would slip away to the washroom and let the chewed flesh fall from my lips into the toilet bowl while I ran water and pretended to wash my hands. I wasn’t sure whether Sylvia ever found out, but lately, except for tonight, it hadn’t mattered when I didn’t put meat on my plate, those nights it was even served.

I popped the triangle of pork into my mouth and held it there, letting the grease seep into my palate. I wondered how long it would take me to melt the meat with my juices, how long I could sit there, squeezing the meat against the roof of my mouth with my tongue before it would dissolve and the pork flesh would become part of me without the aid of my teeth.

I picked up the knife and lapsed into the game Sylvia had slapped my hands for playing when I was younger: mommy fork and daddy knife. I danced them lightly along the edge of the table, thinking of how suave they both were, how debonair, and how they both helped each other. I didn’t notice Sam was home until the bedroom door slammed. Nicky was gone. So was his chop.

With my tongue, I nudged the chewed pork through my teeth. It plopped on the table. I went to the hall doorway. High animal yelps and chokes came from my parents’ bedroom. The fat from the meat made my tongue stick to the roof of my mouth. My whole body was arid, porous. I wanted to see inside the room. I couldn’t hear Sam’s voice. Was he going crazy too?

I tucked in my chin. This was the first time I’d said that word, even if it was only inside my mind. Crazy. I shook my head and widened my eyes. If my mom was crazy I wanted to see everything, to witness all the qualities about Sylvia that put her in this category, to understand what about Sylvia defined her as crazy and took her away from being the mother I had known and turned her into a beast who’d beat herself less than an hour before.

The sounds stopped so I snuck closer, wrapping myself around the hallway’s French door. The bedroom door opened and Sam filled the frame. He was wearing the tight green pants — with the yellow stripe down each leg — of his Tecumseth Chiefs ball uniform and a white T-shirt, his neck and arms a golden red from his first summer burn. He pushed the heels of both his hands against the crosspiece under his gun rack, then jostled past me, reaching back to yank the door shut. For a split second I was able to see inside.

The bedside lamp was on and a thin crack of buttery light illuminated the hallway. A noise like whales keening started up, surrounding me as I glimpsed a white pile on the bed. The noises came from here. The white heap thrashed and moaned but no matter how hard I tried to figure out the angles and limbs and monstrous lumpy middle, it didn’t look human.

Just as Sam pulled the door closed, I caught sight of something more. Beneath the ragged bear hair, the face was red and black and much bigger than a person’s but I knew it was my mother. And knew in that brief wedge-of-light moment before my father’s sun-reddened hand pulled the wrought iron handle and latched the door on my mother, that the face held a secret. A secret I did not want. A secret only I would understand.