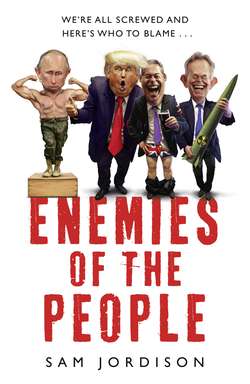

Читать книгу Enemies of the People - Sam Jordison, Sam Jordison - Страница 13

ОглавлениеRichard Nixon

Date of birth/death: 9 January 1913 – 22 April 1994

In a nutshell: US president caught saying bad things on tape – and doing worse all over the world

Connected to: Donald Trump, Milton Friedman, Henry Kissinger, Chairman Mao

For millions of people, watching Donald Trump’s inauguration on 20 January 2017 felt uniquely horrifying. We had never seen such a malevolent, angry, spiritual mess on that podium before. We had never seen so few people on the Washington mall, such a heavy police presence and so many counter-inaugural protests and riots. It felt like something new and frightening.

But it’s the doom of every generation to feel like they’re creating history afresh. Our experience wasn’t so unique. When Republican Richard Milhous Nixon growled out the oath of office in January 1969, there were plenty of people who were just as upset. The famous gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson described the event as ‘a king-hell bummer’. There were violent counter-inaugural demonstrations, there was fear and there was loathing. Nixon’s address to the nation was better received than Trump’s, after he promised to strive for unity and to turn ‘swords into ploughshares’ – but the event still presaged doom to many. Writing a month after the inauguration Thompson predicted that by 1972 there would be ‘violent revolution’ or some kind of ‘shattering upheaval’. As it turned out, he was wrong. But only by a matter of two years.

Nixon today is best known for Watergate, the scandal that brought down his presidency in August 1974. It started off as a small thing – a strange story about a break-in to Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate office complex in Washington, DC. The burglars were found to have a curious amount of cash on them when they were apprehended, and Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward, two junior reporters from the Washington Post, followed that money back to the US president. Nixon had been trying to steal information about his political rivals.

And that wasn’t all. During the course of the investigation it emerged that Nixon had also been secretly taping the White House itself, and his own conversations. Among his sweary tirades came revelations that the original Watergate burglars were being paid hush-money, references to blackmail payments, insults about the American people and shocking revelations about Nixon’s character. ‘He is humorless to the point of being inhumane. He is devious,’ said the Chicago Tribune, up until then a paper that had supported Nixon. ‘He is vacillating. He is profane. He is willing to be led. He displays dismaying gaps in knowledge. He is suspicious of his staff. His loyalty is minimal.’ Ouch.

Watergate was a shocking crime, a landmark in twentieth-century journalism and it ensured that every revelation of a political outrage ever since has had the suffix -gate attached to it. But it wasn’t the worst thing Nixon did.

His life and career was one long assault on decency. One of his most enduring legacies was his ingenious development of negative campaigning techniques. He launched hundreds of attacks on political opponents, hired men to spread false rumours, put out fake press releases to trick newspapers and unsuspecting members of the electorate. Fake news, in other words. And Nixon didn’t only pioneer the spreading of political misinformation – he proved that it worked, in election after election.

Possibly the dirtiest trick he pulled was to delay the end of the Vietnam War in order to undermine Hubert Humphrey, his rival in the 1968 presidential race. Humphrey was the current vice president in an administration whose polling was steadily getting better. If President Lyndon Johnson had been able to end the murderous war in time for the election … Well …

Johnson almost did it too. He had a deal in the works with Russia and the North and South Vietnamese – but a man called Henry Kissinger who had insider information alerted Nixon. Nixon told his aide Harry Robbins Haldeman to ‘monkey wrench’ the peace initiative. He got Republican party operatives to convince the South Vietnamese president to stall the talks (with the promise of a better deal for him if a Republican administration got in). Nixon also told his vice-presidential pick Spiro Agnew to threaten the CIA director that he could lose his job if he didn’t help out. The peace deal fell through. Nixon won the election. The war ground on with the loss of thousands more lives.

And once Nixon got in power, according to Bob Woodward, he used the office of president as an implement of personal revenge. He spent his time trying to get even with people – and bombing the crap out of Vietnam.

Early in 1972, after dropping millions of tonnes of munitions on Vietnam and its neighbours, Nixon sent a memo to Kissinger (who was by then his National Security Advisor), saying he knew the campaign had achieved nothing: ‘K. We have had 10 years of total control of the air in Laos and V.Nam. The result = Zilch.’

This zilch memo was sent on 3 January. The day before Nixon had appeared on CBS saying the campaign had been ‘very, very effective’. He knew there were polls saying people approved of the bombing and taking a tough line. And there was another election on the horizon. So he kept at it. He even ordered more intense attacks. And it worked. Politically. Fresh polls showed that the bombing of Vietnam remained popular. ‘It’s two to one for bombing,’ Kissinger said, triumphantly. In that year, the US dropped 1.1 million tonnes of bombs with the ruination and loss of thousands and thousands of lives and no military gain. No matter. Kissinger remarked in October that one particularly intense raid on 8 May had ‘won the election’ for Nixon.

But of course, just twenty days after that brutal raid, the botched Watergate break-in occurred. Within a couple of years, Nixon was fighting for his political life, attacking the press, doing his utmost to undermine the judiciary who were holding him to account, and lying and lying about it all to his electorate. ‘People have got to know whether or not their president is a crook,’ he said during a televised Q&A in November 1973. ‘Well, I’m not a crook. I’ve earned everything I’ve got.’

Alexander P. Butterfield, deputy to H. R. Haldeman and the man who revealed the existence of Nixon’s secret tapes, didn’t agree. ‘The whole thing was a cesspool,’ he said years later. The public saw it that way too. By August 1974, Nixon saw the writing on the wall and resigned. He spent the next twenty years before his death in 1994 maintaining that he hadn’t done anything so very wrong.

Hunter S. Thompson wrote his obituary for Rolling Stone magazine. First line: ‘He was a crook.’ Unfortunately, Thompson didn’t survive to see Nixon’s spiritual successor Donald Trump take office. Nor to lament the fact that Nixon had predicted and endorsed Trump’s candidacy back in 1988, after the then real-estate magnate appeared on a TV show. ‘I did not see the program,’ wrote the disgraced president, ‘but Mrs Nixon told me that you were great … As you can imagine, she is an expert on politics and she predicts that whenever you decide to run for office, you will be a winner!’

Thanks, Nixon.

Other scandals ending in -Gate

Nipplegate – relating to a ‘wardrobe malfunction’ that exposed one of Janet Jackson’s breasts during the half-time show of the 2004 Super Bowl.

Betsygate – allegations that leading pro-Brexit Conservative MP Iain Duncan Smith put his wife Betsy on his payroll without her doing any work.

Camillagate – the release of a taped conversation in which Prince Charles said he’d like to live inside Camilla’s trousers. Maybe as a Tampax.

Monicagate – named after Bill Clinton’s relations with his intern Monica Lewinsky.

Piggate – the allegation that David Cameron put his penis where he ought not to have put his penis at a dinner party where whole pig heads were served.

Pussygate – taped conversations with Donald Trump declaring he’d like to kiss a woman and that ‘when you’re a star, they let you do it. You can do anything … grab them by the pussy.’

And, best of all: Gategate – the allegation that Tory minister Andrew Mitchell called a policeman a pleb when asked to use a different gate to leave Downing Street on his bicycle.