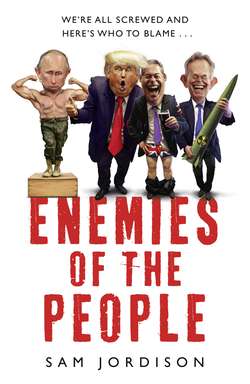

Читать книгу Enemies of the People - Sam Jordison, Sam Jordison - Страница 14

ОглавлениеChairman Mao

Date of birth/death: 26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976

In a nutshell: Killed millions of people for the sake of communism – but actually helped usher in an age of ultra-capitalism

Connected to: Henry Kissinger, Richard Nixon

Just like Milton Friedman and Ayn Rand, Mao Zedong had big economic theories and he was determined to put them into action. Just like Rand and Friedman, he would claim he had reached his ideas through ‘objective analysis’. Just like Rand and Friedman, he made life miserable for millions.

But unlike his two capitalist mirror images, Mao believed in central planning rather than market forces. Unlike Friedman and Rand, he also didn’t just leave the work to acolytes. Mao got his hands dirty.

When he got to power in 1949, Mao had already had a good twenty years of fighting for Communism. He’d been hard at it since the late 1920s and – to the immense misfortune of everyone around him – had had an awful lot of luck.

Probably his biggest break came in the Long March of 1934–35 where Mao beat the odds (partly thanks to his willingness to abandon children, the sick and the elderly) to hurry 100,000 people away from encircling nationalist forces.* But even after that, his ascent wasn’t a foregone conclusion. If the Japanese had not invaded mainland China in 1937, things might have been very different. They simultaneously distracted the Nationalist government, while forcing more and more people into the Communists’ arms with their acts of brutal repression. After the Nanking massacre, for instance, the Red Army grew from 50,000 to 500,000 strong. And it kept on growing until Mao’s last enemies surrendered in 1949.

By this time Mao had already caused thousands of deaths. At the Siege of Changchun alone, his forces killed as many people as the bomb on Hiroshima. ‘Peaceful methods can not suffice,’ he said – and he stood by this principle for the rest of his life. He also stood by his private swimming pool. He was said to most enjoy dictating policy from beside the water. When he wasn’t in bed, anyway. Yet while Mao was renowned for being personally lazy, he also got an awful lot done.

One of the chubby chairman’s big theories was that China should change from an agricultural to an industrial economy – farming should be collectivised, and targets set for grain production and distribution. He called this the Great Leap Forward and began to put it into practice in 1957. By 1958, he was telling his inner circle that: ‘Working like this, with all these projects, half of China may well have to die. If not half, one-third, or one-tenth – 50 million – die.’

It turns out that last figure wasn’t a bad estimate. Scholars now say that the famines caused by the Great Leap Forward, the requisition of grain based on falsified figures for harvests, and related droughts and flooding killed between 15 and 45 million people.

Following this disaster, Mao lost some of his grip on power. Members of the Communist Party began liberalising the economy and undoing his Marxist reforms – although Mao kept his grip on the army and the ruthless secret police force he’d been building up over the past decade or so. He began to mobilise again. Demonstrating a fondness for the word ‘great’ that would be unmatched until Donald Trump came to power, he next instituted the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution of 1966.

Predictably enough, ‘great’ turned out to be a serious misnomer. The Cultural Revolution was unremittingly awful. The basic premise here was that there was too much of an elite in China, that the people should be placed in direct control of everything, and that Mao and his newly fanaticised followers in the Red Guard were really, really sick of experts. Thousands of schools and universities across China were closed. Intellectuals were forced out of the cities to be ‘re-educated’ by peasants in the countryside. More millions were killed. Oh well, said Mao, ‘China is such a populous nation, it is not as if we cannot do without a few people.’

During the Cultural Revolution Mao also made sure that his extreme vision of Marxism–Leninism was put back into practice. Private enterprises were nationalised, and private property was taken under state control. But such reforms didn’t last much beyond his death in 1976. His successors quickly began dismantling them and opening China up for trade and market reform. The thing they didn’t dismantle was Mao’s one-party state and its powerful system of repression: the giant army, the ruthless police and subservient media. Ironically enough, these were the very things that enabled the Chinese government to push through rapid capitalistic reforms in the 1980s, crush the resistance to them at Tiananmen Square and then go on to set up rigorously policed enterprise parks all over the country. If it wasn’t for Mao’s state apparatus, China wouldn’t have been able to build and maintain the low-tax, low-regulation, high-security and maximum-secrecy fenced-off zones where cowed and subservient workers manufacture so many cheap consumer goods.

So it is that Mao’s most enduring legacy lies in feeding the global capitalist machine he despised. We have him to thank for our smartphones. But also for the fact that so many Western countries have become post-industrial wastelands. Places with low job security and frightened voters looking to demagogic leaders like Donald Trump who promise to bring them jobs again. Actually, come to think of it, maybe Mao will help bring down capitalism after all …

In 1973, Nixon’s Secretary of State Henry Kissinger visited Chairman Mao. Mao had a lot of problems on his mind, chief among them, women.

‘Let them go to your place,’ he said to Kissinger. ‘They will create disasters. That way you can lessen our burdens … Do you want our Chinese women? We can give you 10 million.’

Dr Kissinger laughed that Mao was ‘improving his offer’.

Mao went on: ‘By doing so we can let them flood your country with disaster and therefore impair your interests. In our country we have too many women, and they have a way of doing things. They give birth to children and our children are too many.’

‘It is such a novel proposition,’ said Kissinger. ‘We will have to study it.’

The leaders next spoke briefly about the threat of nuclear apocalypse posed by the Soviet Union, but Mao was soon back with bigger concerns:

‘We have so many women in our country that don’t know how to fight.’

At this point, US State Department papers show that the Assistant Chinese Foreign Minister, Wang Haijung, cautioned Mao that the public might get annoyed if they found out what he had been saying. Kissinger and Mao agreed to strike the words from the record. They were only made public in 2008.

* Mao made sure he didn’t tire himself on the march too much. He was carried lots of the way on a litter, filling in the time reading books.