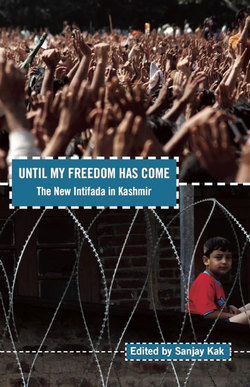

Читать книгу Until My Freedom Has Come - Sanjay Kak - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеHow I Became a Stone-thrower for a Day

Hilal Mir

I left Kashmir a year ago to preserve my sanity, frayed during the past two decades by the internalizing of the conflict. Covering it as a reporter for seven years felt like wading—despairingly—through the five rivers of Hades. My emotions stabilized a bit by the speed and normalcy of life in Delhi, I thought I could now maintain a safe distance from the happenings. With this frame of mind, I landed on 4 July at Srinagar airport on a vacation.

Policemen and paramilitary soldiers were everywhere along the way. Driving me home, my friend Showkat, Outlook magazine’s Kashmir correspondent, prepared me for the situation by narrating the horror he and a bunch of journalists from the Indian Express, Sahara Samay and Tehelka had faced a day before. While covering a procession marching toward the north Kashmir flashpoint of Sopur, they had been fired at by a policeman on the Srinagar highway. Shouting aloud about their press credentials had only invited abuses. They had to take cover in the nearby paddy fields, surprised that the bullet missed them. Showkat’s wife had since asked him to quit journalism and raise chickens. It was the only day I saw shops open and traffic plying normally. From the next day, it was a return to the realm of Hades.

In the morning, one and a half kilometres away from my home, I went to the funeral of a seventeen-year-old blue-eyed, fair-skinned student, as handsome as Omar Abdullah, and a thirty-five-year-old father of two. According to the protesters, the boy had been hit in the head and then thrown into a flood channel by the police. The man had been shot dead during the boy’s funeral procession. Women wailed, pulled out their hair, beat their chests and faces, and men shouted freedom slogans while the duo were consigned to the graves. I had seen this countless times in the past, but the rage this time was volcanic, fuelled largely by official lies, apathy and the validation of the bullet-for-stone method. People wanted revenge—though, at the same time, they were aware that their acts of revenge, stone throwing at best, would result in more deaths. It seemed a rage directed more towards one’s helplessness than towards an armed soldier. Otherwise why would such ‘frenzied mobs sponsored by Lashkar-e-Toiba’ not kill a soldier they had cornered on a road, but instead just beat him up, strip him and let him go?

This strange mix of rage and helplessness was to strike me and several journalists I was moving around with in the curfewed, restricted and deserted city. A Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) soldier stopped us in the old city. A young reporter of a local English daily showed him a curfew pass issued by the government. The soldier tore it up and asked, ‘Where is your bloody curfew pass now?’ I had had no time to get a curfew pass. I just showed my Hindustan Times ID card. I presume the word ‘Hindustan’ did the trick.

The next few days were spent in exhausting discussions on politics, in parks and the Mughal Gardens, leaving us with an aftertaste of impotent rage. The calm instilled by Delhi was wearing thin. I had always loathed the term ‘objectivity’ when it really meant balancing truth with a healthy dose of falsehood—or, even worse, ‘national interest’. Much of the media were doing that. The state and central governments were in a state of denial, effectively blaming the people for the mess. For the first time I felt like an ordinary Kashmiri and wanted to react like them. I was with other journalists when we went to Kawdara in the old city, where separatist leader Mirwaiz Umar Farooq was leading a demonstration that soon morphed into a clash between youth and CRPF soldiers (camping in a bunker as old the insurgency itself).

I picked up a stone from the debris of the housing cluster burnt by CRPF soldiers in 1990 and threw it at the soldiers, a few of whom were filming the stone-throwers with mini-cams. Caught, I could have been booked under the Public Safety Act and jailed for two years without a trial. I would also have been jobless because no news organization would have a felon on its desk. But I threw more stones. I later realized it was an atavistic reaction, as if it was the only legitimate thing to do in that cursed place. I had thrown stones twenty-three years ago when three people were killed for demonstrating against a hike in power tariff, an event that would catalyse the uprising of 1989. My journalist friends restrained me. Disoriented, I walked to my birthplace, Nawab Bazaar, in the old city, a kilometre from Kawdara.

Nawab Bazaar was as furious as it was twenty years ago. Angry youths whom I had seen growing up were pelting the CRPF bunker there with stones. Back then, militants had attacked it with AK-47 rifles. For me, the bunker represents an occupation of memories. It was built on the spot where a man sold phirni and children would line up for the sighting of the crescent, a harbinger of Eid. A short distance away, the Dogra maharaja’s soldiers had shot dead my great-grandfather in 1931. Twenty years ago, when the bunker was being constructed, my father’s bosom friend, a fanatical Congress supporter, prophesied that ‘your eyelashes will turn grey, but the bunker will still be there’. He died last year. His eyebrows had started to grey and all his hair was silver.

Old demons were stirring up inside me. During nights I would look out of the window of my room, holding a digital recorder in any hand to catch freedom songs blaring from mosque loudspeakers and wafting through the quiet air. Twenty years ago I had heard and sung the same songs. The bunker in Nawab Bazaar has grown bigger and uglier, with all those barbed-wire loops, fences, gaudy paint and slits, demonstrating that the state does not tire. But neither do the people.

A shorter version of this first appeared in the Hindustan Times, New Delhi, 7 August 2010.