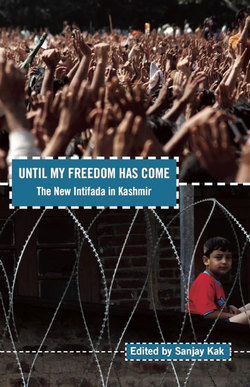

Читать книгу Until My Freedom Has Come - Sanjay Kak - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe Fire Is at My Heart

An Introduction

A way from the tumult of its streets, away from the heady slogans, from the explosive whoosh and clatter of tear-gas shells, and the deadly crackle of live ammunition, one moment returns from Kashmir’s turbulent summer of 2010. It insinuates a place for itself, a whispered observation of oddly unsettling precision.

Mummy, mae-ae aav heartas fire. Mummy, the fire is at my heart.

These were the last words spoken by twenty-four-year-old Fancy Jan as she turned away from the first-floor window of her working-class home in downtown Srinagar that July morning. She was reaching for the curtain, her family said, to keep out the acrid teargas smoke floating in from the streets of her volatile Batmaloo neighbourhood. (The window lacked glass-panes; the room was still being built.) The ‘fire’ she had drawn into the privacy of her home was a bullet, and she dropped dead soon after, a victim of a casual brutality, of a weapon fired carelessly by one of the hundreds of police and paramilitary soldiers on the streets outside.

Fancy Jan was one of a handful of women killed in the summer, in this most recent upsurge in Kashmir’s tortuous history. The rest were young men in their twenties, but many were just teenagers—boys, really. That grisly calendar had been quietly unveiled early in January 2010, when sixteen-year-old Inayat Ahmad was shot dead by paramilitary soldiers in the heart of Srinagar. On 31 January, a thirteen-year-old was killed when a tear-gas shell fired by the Jammu and Kashmir police hit Wamiq Farooq on the head. Less than a week later, as sixteen-year-old Zahid Farooq returned from an evening’s cricket with his friends, he was shot dead by a passing Border Security Force patrol. His killing may have been provoked, we are told, because the boys had jeered at the passing vehicle of a senior officer.

The years since 1989, when the uprising against Indian rule first began, have been bloody for Kashmiris. The militancy, initially armed and supported by Pakistan, was quick to draw the full weight of the Indian sledgehammer. For Kashmiris, the insurgency, and the counter-insurgency that was unleashed to flatten it, ended up shredding the everyday fabric of life. The sheer force of India’s massive military commitment may appear to have overwhelmed the armed militancy, but twenty years of this presence has resulted in a deeply militarized society. With well over 6,00,000 army, police and paramilitary personnel already deployed in Kashmir, the numbers that go into holding down a rebellious population are clearly at saturation point. Today the Kashmir Valley has the highest concentration of soldiers in the world—more than Afghanistan, Iraq or Burma. It is only in the last five years that the shape of this intervention has been dragged out of the guarded penumbra of Indian ‘national interest’. Away from that shadowy protection, it now stands increasingly exposed as a clumsy attempt to overwhelm, with sheer force, that obstinate, often inchoate, but in the end, very political desire for Azadi—freedom.

These decades of a silent, undeclared war have extracted an enormous price: seventy thousand Kashmiris have been killed since 1989, and eight thousand have gone ‘missing’. To this must be added the less visible costs of torture, rape, life-long physical incapacities and grievous economic, social, and psychological damage. The extent of this devastation will probably never be fully estimated, but its restive contours are beginning to stir under the blanket silence that has enveloped Kashmir for most of this recent past. The long-whispered murmurs about the existence of mass graves, for example, found confirmation only in 2009, when a civil society group patiently assembled a list of their locations. (The International People’s Tribunal on Human Rights and Justice in Kashmir has recorded nearly 3,000 such unknown and unrecorded graves.)1

Word of one such unmarked grave, in the faraway forests of Machil, in Kupwara, north Kashmir, arrived in the month of May 2010. It was news because it was still a fresh site: three unarmed civilians had been killed, shot in cold blood by soldiers of a Rashtriya Rifles unit, the specialized counter-insurgency force of the Indian Army. The bodies had been buried anonymously, and then announced as those of militants killed in an ‘encounter’. Such calculated venality is not unusual, except that it had become public in time, and news of it had reached the already volatile streets of Srinagar.

It was on the fringes of one of these protests that another lethally aimed police tear-gas canister took apart the skull of seventeen-year old Tufail Matoo, as he walked home from his tuition class. This was already June. Tufail’s killing set off huge, emotionally surcharged demonstrations, unprecedented even by Kashmir’s overwrought standards. A civilian killed inevitably led to other killings by the police and paramilitary soldiers. Sometimes there were several in a day. Then more protests, and more killing. In four months of this bloody oscillation 112 people had been shot dead on the streets of Kashmir.

Summer has gradually emerged as the season for a face-off, played out almost ritually in the Valley. India comes wearing the mask of what it calls its ‘security’ forces—the army, paramilitary and police personnel it deploys. And confronting this well-entrenched military machinery have been thousands of young men who have taken on the soldiers in a kani jang—a war with stones.

Perhaps it is the extraordinary duration of its troubles that’s given Kashmir’s summer this sharp edge. You could date its origins to the anti-feudal struggle against its autocratic maharaja in the 1930s. Or say that Kashmir is the unfinished business of the end of Empire, of the Partition of British India, carved up into India and Pakistan in 1947. Either way, that still makes it one of the oldest unresolved disputes in the world. Or maybe it’s just the skin of its people that has worn thin over the long years of this uprising. The gentle warmth of its June sun now seems enough to stoke up a volatile impulse, and provoke people to take their places outside of their homes, in the streets, in protest.

So every year since 2008, just when Indian security forces think they have a firm grip on the situation, the incendiary arrival of summer reduces the patrolling police and paramilitary forces to puzzled bystanders. Then they can only watch, as people reclaim the streets, coming out in massive demonstrations, sometimes hundreds of thousands strong, and noisily destroy the silence imposed on them. Several decades after the idea of Azadi was first voiced openly in the towns and villages of the Valley, one slogan, chanted endlessly, continues to dominate this tumult.

Hum kya chahte? What do we want? Azadi! Freedom.

Sceptics in India, eager to contain Kashmir within the beleaguered imagination of the Indian nation-state, will continue to tirelessly interrogate the many uncertainties packed into that fraught word: freedom. But in the summer of 2010, protesters in Kashmir unambiguously spelt out at least one of its oldest meanings. On a blackboard of macadam, they scrawled in large white letters: Go India. Go back.

This is no ordinary rejection, for it comes at a time when India has ambitiously invited itself to the select ring of global superpowers, parlaying its potential for economic growth, and the lure of its huge markets, into greater international clout. With a standing army that is more than 1.3 million strong, India does appear ready to be part of this club of the powerful: there are ambitious whispers of a seat in the United Nations Security Council.

Yet, in 2010, with at least half of its huge army deployed in ‘securing’ Kashmir, India’s fierce grip was frequently beginning to look slippery. A vast and often brutal counter-insurgency grid, an all-pervasive system of surveillance and intelligence-gathering, tight control over the media—yet nothing seemed to be giving India traction. With the place of the gun-wielding mujahid rebels of an earlier generation now taken up by these unarmed civilians, you couldn’t help notice that the very long embrace with militarization had seriously dulled the government’s reflexes.

India has historically—and systematically—circumscribed the political space for the ‘separatist’ sentiment in Kashmir. Having driven it underground in the 1970s, and into armed rebellion by the end of the 1980s, a long and humiliating history of rigged elections followed. A cynically imposed superstructure of what are locally called ‘pro-India’ parties, but are really disempowered proxies, now play out an elaborate charade of democracy. Faced with a massive upsurge in 2010, the Indian state seems to have reacted in the only way it knew. It ratcheted up the mechanisms of coercion.

Two recent images reflected this response. The first was a cosmetic makeover for the patrolling soldiers, as the paramilitary were deployed on the streets in futuristic new protective body-gear. This brittle air of menace, ‘Darth Vader in cheap black plastic’, as one acidic commentator in Srinagar called them, was shored up by new ‘non-lethal’ measures of crowd control. Proudly announced by the mandarins of the home ministry in New Delhi, they included a pressure-pump pellet-gun that shoots out hundreds of high-velocity plastic pellets simultaneously. (On the very first day it was used, in Sopore town in north Kashmir, a paramilitary soldier fired the ‘non-lethal’ gun at close range, and killed a man.)

More telling evidence of this battlefront panic was another, less obvious weapon that the paramilitary soldiers took to. Unable to stem the tide of protesters, and with a kill rate beginning to average one civilian a day, the soldiers began to aggressively use slingshots. They were loading catapults with a vicious charge of glass marbles and sharp pebbles, and this abomination led to permanent damage to the eyes—and sometimes even blindness—for scores of young protesters. But it didn’t kill them, which would have been bad for public relations.

In the full glare of the public eye, the contrast could not have been more stark and, in the end, more damaging for India’s image as a showpiece of Democracy at Work. Though padded up in their black armour, the soldiers appeared daunted by the raw courage of the young men. The stone-throwing sang-baz, in turn, with their faces covered, and their chests often bared, were seen as taunting and provoking the soldiers. A few hundred people on street corners in Kashmir were suddenly able to show up the emerging superpower.

It is these images of naked courage that allowed people in Kashmir to tremulously make a connection with the long and heroic resistance of the people of Palestine. And refer to the summer of 2010 as their intifada, the ‘shaking off’ of the chains of occupation.

Hindsight has made a prophecy of a dying whisper.

Mummy, mae-ae aav heartas fire. When that bullet tore through Fancy Jan in July 2010, the fire had indeed reached the heart. Something massive had been breached, and this may well have been the tightly controlled knot of memory of a new generation of Kashmiris. Unlike many others in the last twenty years, the brutal deaths of Inayat, Wamiq, and Zahid, and the meaning of their killing, were not easily interred at mazar-e-shouhda, the martyr’s graveyard. These were taken note of, and written about extensively; word was passed on and debated, and memories of struggle revived in very distinct ways.

Young people were dying, and it was other young people who ardently remembered them. This was a generation that had grown up within the searing conflict of the past two decades, but even amongst Kashmiris they had been frequently (although inexplicably) represented as apolitical, as disconnected, as innocent victims. Young Kashmiris, we had been told, had moved on, distracted by beauty parlours, coffee shops, pool tables and Internet cafes. The furious footfalls of the last three summers quickly rubbed away that spurious patina, making it clear that the young protesters refused to see themselves as outside of the events around them. The almost daily killings did little to subdue them, making them only more eager to be part of the confrontation.

This stepping out of young people on the streets was a major consequence of the recent transformation in the nature of the uprising in Kashmir. The strategic shift from the militant’s gun to unarmed—if stone-pelting—protest was nothing short of tectonic. Yet every attempt was made to disregard this reality, and the government and the media tried to run every possible spin on it. The crowds were mobilized by the Lashkar-e-Toiba, they said; these were hired goons paid for by Pakistan; they were drug-addicts who pelted stones only because they were on a high; they were social malcontents; urban detritus. The attempt to tarnish a reality that was quite evident to everybody may even have succeeded, but sometime in the middle of the summer of 2010 someone in the security establishment inadvertently pressed the wrong switch. With stifling curbs on the local print and television media already in place, a panicked government blocked the popular text messaging service on the cellphone network, a critical artery through which news—and rumour—circulates within Kashmir. For the next six months, subscribers could only receive commercial messages on their cellphones. (In the midst of adversity, a bonanza for advertisers!)

Choked at one place, news in Kashmir quickly found another way to move—travelling like quicksilver through the newly arrived phenomenon of Internet-based social networking sites. Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube had emerged as a critical arena of contestation in Kashmir. Instead of only speaking to each other, Kashmiris were suddenly speaking to the world.

Daily, and sometimes hourly, updates on the protests began to appear. Within days the response to the Aalaw (the Call) group had clocked up thousands on Facebook. (Today it has 17,500.) Bekar Jamat (Union of Idlers) signed up nearly 12,000, offering methods of dealing with the effects of tear gas, and even first-aid tips for shooting victims. When Bekar Jamat was mysteriously hacked, it cheekily reappeared as Hoshiar Jamat (Union of the Vigilant). Like the covered faces and the bared chests of the young stone-pelters on the streets, the identities were a message in themselves: Aam Nafar (Ordinary Guy), Dodmut Koshur (Burnt Kashmiri) and Karim Nannavor (Barefoot Karim) joined other proletarians, like Khinna Mott (Snot Crazy), Nanga Mott (Naked Crazy) and Kale Kharab (Hot-head). Meanwhile ‘Oppressedkashimir1’ was recording video images of the street protests, probably on his cellphone, and joining dozens of others in uploading them on YouTube.

Through the summer, as the stones pelted on the streets held down the police and paramilitary forces, a simultaneous barrage of news and commentary on the Internet had equally serious consequences for the mainstream Indian media. Unused to any sort of scrutiny, comfortable and unchallenged in their representations of the unfolding situation, the protection of the newsrooms was suddenly not swaddled enough for the journalists and television anchors of New Delhi. They found themselves inundated with alerts and corrections, and inevitably, some abuse. International observers had the equivalent of a ball-by-ball commentary of street battles, with a rich context that was impossible to ignore. Watchful young people from small towns across Kashmir were reminding the Indian establishment that communication on Twitter was two-way, and that Facebook was, after all, available to millions on the worldwide web.

A deluge of well-argued commentary and analyses began drawing in the intellectual resources of a virtual community from across the world, and these were not all Kashmiris either. Suddenly there were vibrant alternatives to the stale shibboleths of the official Indian line, challenging it at every step. The protests on the ground were also able to provoke the international community into a new appreciation of events in Kashmir. Where not so long ago masked gunmen had read out old-fashioned press releases from one or the other militant tanzeem, there was now a massive opening out of the language in which Kashmir was being spoken about. On the Internet, there was news, and analyses, but there was also a spate of music videos, which cut images from this week’s protests (usually shot on cellphones) into next week’s rousing protest anthem. ‘Stone in My Hand’, by the radical Irish American rap singer Everlast, was an early, and unexpected, hit. Young stone-pelters were known to cruise the streets listening to the song (naturally on their cellphones). There were stories, often elliptical, yet highly political, including a short graphic novel exquisitely drawn in black and white, about the Kashmir ‘Intifada’. And it was the Internet again that would soon carry out the words of teenaged Kashmiri rap artists, like the nineteen-year-old MC Kash, ‘Coming to You Live from Srinagar Kashmir’, as he promised. As the summer slowly wound down, it was impossible not to be snagged by the closing lines of his runaway hit, ‘I Protest’:

I Protest, Fo’ My Brother Who’s Dead!

I Protest, Against The Bullet In his Head!

I Protest, I Will Throw Stones An’ Neva Run!

I Protest, Until My Freedom Has Come!

A recitation of names followed, a flat monotone for the summer that was going past. ‘Let’s remember all those who were martyred this year—Inayat Khan, Wamiq Farooq, Zahid Farooq, Zubair Ahmed Bhat, Tufail Ahmed Matoo, Rafiq Ahmed Bangroo, Javaid Ahmed Malla, Shakeel Ganai . . .’ (Halfway through that seemingly endless litany and I had almost missed the name I was listening for—Fancy Jan, under her formal name, Yasmeen Jan.)

These were young people born into this conflict, and they seemed to have absorbed everything that history and circumstance had thrown their way. When the sixteen-year-old ‘Renegade’ rapped out a ‘Resistance Anthem’, speaking of ‘lyrical guerilla warfare’, and fighting with ‘knowledge and wisdom’, it was a clear signal that something had changed. This new generation was taking up its place on the streets, and these were the sites for the new battle—some filled with stones and tear gas, others with words and ideas. But these two struggles did intersect in some unusual places, and the handshake was unexpectedly warm.

Amidst all the bloodshed, the summer of 2010 was an oddly hopeful time, and much that was repressed was finally beginning to come out in the open.

‘I can hear birds,’ a friend called in to say that morning in September. Unusual, because you don’t often hear birds in Srinagar. Not for the roar of its chaotic traffic, and for the past several months of the summer of 2010, not for the tumult of the streets.

‘But nothing else,’ he added in a brittle voice, ‘I hear nothing else.’

It was the day after Eid, usually a day of continuing celebration, for it marked the end of the month of Ramzan. In the past two years it was the physical rigours of just this month of fasting that had finally leached the flagging energy from those immense agitations. This year was different though: after nearly four months of protests, and with 112 people killed, the onset of autumn gave no indication of a slowdown in the tempo. The visible faces of the ‘separatist’ sentiment were all in custody. But from somewhere far underground other anonymous organizers were still able to issue the ‘timetable’, as the relentless calendar of the hartal protests were locally known. By supporting these, despite the enormous dislocation and deprivation that the shutdowns caused, people were continuing to signal their fierce support to the revolt.

Retribution for such insolence was inevitable, and when it came, it was as fierce. The government began to impose its own calendar of harshly enforced shutdowns. These were usually timed for the days of relief in the carefully calibrated ‘timetable’. Curfew was rarely declared though, but enforced through its extra-legal local variant, the ‘undeclared’ curfew. Put together—people’s curfew and police curfew, end-to-end—it meant that people in the cities and towns of Kashmir were often unable to step out of their homes for most of a week. No milk, no bread, no vegetables; no infant food, no doctors, no medicines—nothing.

When the friend called the day after Eid, there was no food in the house, and little to celebrate with. The paramilitary forces were smarting from events of the previous day, when a relaxation in the curfew had seen massive protests erupt in the very heart of Srinagar, in Lal Chowk. When he tried stepping out of his home, the soldiers in the sandbagged bunker outside had threatened to shoot him. ‘You can stuff that pass up your arse,’ they had said firmly when he walked up, holding his journalist’s curfew pass like a white flag. He called their superior, the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) Public Relations Officer, to describe what was going on, conspicuously holding his cellphone up, speakers on. The men were even more emphatic now. ‘Call him too,’ they said of their officer, confidently. ‘Call him here, now. We’ll stuff it up his arse too . . .’

This quick tightening of the tourniquet was carefully timed. In the nerve centres of the uprising—in Sopore in the north, and Shopian in the south—late September was also the time to bring in the abundant apple crop. To turn their backs on it, or do it badly, would spell ruin. This is what makes autumn critical in the predominantly agricultural economy of rural Kashmir, with its anxious prospect of being unprepared for the difficult winter ahead. An unspoken tactical withdrawal was materializing.

The silence surrounding the birdsong presaged the most severe repression that Kashmiris have experienced in a decade. And once again it was in the countryside, away from even the minimal scrutiny of the media, that the brunt of the renewed aggression would be borne. Only thirty kilometres north of Srinagar, the rebellious village of Palhalan had its phone lines snapped, its mobile phone services disabled, and physical access to it made nearly impossible for outsiders. At a highway checkpoint, if your identity card carried the name Palhalan on it, you were likely to be pulled out of a public bus, and made to walk. Students from the village were summarily ejected from examination halls, and taken straight to detention. Before the year was out, Palhalan had endured almost two-and-a-half months of curfew, including one straight stretch of thirty-nine days.

No defiance was too small to be ignored. In the remote fastness of Kulgam, paramilitary soldiers surrounded Kujar village, and asked everyone to step out of their homes. They then stood guard as the police moved in, first smashing all the precious windowpane glass, and after that, with pointed cruelty, systematically destroying the kitchen. There was no media on hand to report any of this at the time, but even if they were, what would they be saying? ‘Police smash windowpanes’? ‘Paramilitary destroy kitchen’? No one had been killed, or even seriously injured. Who would care to understand the significance of this brutalization? Meanwhile in Srinagar and other towns, Facebook groups had begun to be infiltrated, and outspoken members tracked down through their IP addresses. The mostly teenaged net warriors were systematically called in to the local police station for questioning, and the threat of worse to come.

As chila-e-kalan, traditionally the coldest part of Kashmir’s winter, placed its freezing hands on life in the Valley, the police seemed to be slowly coming into their own. Increasingly triumphant stories were being released to the press: Irfan Ahmed Bhat, a seventeen-year-old from Nagin, Srinagar, had been detained for questioning, they said, suspected of being the dreaded Kale Kharab of Facebook2. Records were being created, a police spokesman said, depending on the ‘level’ of involvement. ‘In Group A habitual protesters and stone-pelters would be inducted,’ we were informed. ‘In Group B only those people who have fervently participated in protests and initiated stone pelting will be listed; and Group C includes those persons who have been once lodged in the jail for any unlawful activity.’3 Stone-pelters were being hunted down with the dogged tenacity that not long ago had been reserved for armed militants. The politics of the summer upsurge were being drowned under an endless series of stories that tried to represent the protesters as delinquents, even criminals.

As the smug triumphalism of government propaganda readied to fill the media space, and claim yet another spectacular success against the separatists, a warning wafted off the streets, like a sullen fog.

Khoon ka badla June mein lenge, it said.

Blood will be avenged, in June.

In the new year, with the snow still thick on the ground, Kashmiris drew warmth from faraway Egypt, from the gossamer hope that the masses of people in Tahrir Square—ranged against tanks and soldiers, and the faraway machinations of powerful empires—might still bring about change for Egyptians (and eventually, for the interlinked fortunes of Palestine, and the entire Middle East). The Internet had proved to be a valuable resource in Egypt, threading together the gathering forces of change. And it was on Facebook that many young Kashmiris noted the Western world’s embrace of the revolt in Egypt, wondering why it was so much more circumspect about the 112 young people killed in Kashmir.

But hope had already been put on notice. Imperceptible at first, but palpable when you put your ear quietly to the ground, we watched the euphoria of the summer, and its openness, in retreat. With the revolt in the street having exhausted itself, and the young people made to cede that space, the pressure on the Indian state was missing. Even the political resistance of the Kashmiri ‘separatists’ seemed unmoored now. In the summer they had seemed to be out there, in touch with the people, but now found themselves forced right back into the corner painted for them.

The highest ranking Indian Army general in Kashmir took the time to step outside his brief and accuse social networking sites of being ‘used as a tool of propaganda against the army and other security agencies, by elements hell-bent on disturbing peace in the Valley.’4 When the press asked for an update on the army’s fake ‘encounter’ of three civilians in Machil, the incident which first triggered the avalanche of protests, he was more taciturn, saying he had no comment, and the matter was ‘sub judice’.

A top-ranking police officer told the press in Srinagar that of the 1,000 young men they had detained, 72 per cent were social misfits, either drug addicts, or people with problems at home. Waving a picture of a young man attacking a police jeep with a stone, he said ‘They do such acts of heroism only under the influence of drugs.’

Meanwhile, from an exhibition of defence products in faraway Bengaluru came news of a new toy on offer to security forces in Kashmir—a US-made ‘pain gun’, which sends out beams of radiation that stimulate human nerve endings, causing extreme pain. It ‘barely’ penetrates the skin, Raytheon, the global weapons giant, promised, so the ‘ray gun’ cannot cause visible or permanent injury.5 A step ahead then, from last year’s catapults, which blinded so many young men on the streets of Srinagar. (The US military first used this Silent Guardian Protection System in war-torn Afghanistan, but withdrew it last year, amidst opposition from human rights activists.)

Khoon ka badla June mein lenge. Blood will be avenged, they had said.

Who will retaliate, I wonder, and what will be avenged, this coming June, and in the summers to come?

From Sopore, heartland of the pro-Azadi movement, comes news of the killing of two young women, seventeen-year-old Arifa and nineteen-year-old Akhtara. They had been warned twice, neighbours said, explicitly told to break links with security forces. Sopore had seen handbills recently, warning people not to consort with police, military or intelligence people. On the day of their cold-blooded execution, bystanders confirmed that more than a dozen men brazenly walked into the neighbourhood, a few went in to meet the girls, while the rest stood guard on the street. Arifa and Akhtara were later taken away, and killed a bare twenty minutes away from their dingy one-room home. All evidence pointed to the Lashkar-e-Toiba.

So there they were, the Lashkar, that ruthless Army of the Faithful, trained to destroy and dislodge, back after several years of lying low. The quiet rumble of public opinion had discreetly made them concede the resistance to the mass of people, to the stone-pelters, to the open street. As the police hunt down the sang-baz, grade them in categories A, B, and C, and put them in jail; as they take in the hot-headed Kale Kharab, and smash windowpanes in town and village, people are once again being forced to step back. The tired, sullen silence of the street will inevitably create a vacuum, and make space for the old fighters to return. It will be an invitation to the earlier ways, of armed resistance, of the Hizbul-Mujahidin, and heaven forbid, the Lashkar-e-Toiba.

In the 1990s, this valley was also drawn into the cauldron of war by its neighbours, as the defeat of the Soviet Union in the mountains of Afghanistan redirected the energies of the mujahidin into Kashmir. That neighbourhood is teetering dangerously again. Preparing for defeat this time is the United States, shadowy victors of that earlier war, even as they try to dress it up as a strategic withdrawal.

There is an ominously familiar feeling in the air.

The fire is indeed at the heart.

This collection brings together a diverse set of responses to the events of 2010, a time of great upheaval in Kashmir. It seemed as if the events and ideas that have animated the struggle of its people had, after almost twenty years of a muted, subterranean existence, entered a new phase. A time marked—we imagine—by openness and candour, and by a diversity of opinion.

Most of what appears here came in a furious rush in the summer itself, and reflects the intensity of what people were responding to. The chill of winter was yet to settle in. It is left to the readers to discover what runs common through the range of ideas in Until My Freedom Has Come. But attention can—and must—be drawn to the hope that attends this volume. As always, we know we can trust Agha Shahid Ali, Kashmiri poet, to make eloquent our present hopes—and ever-present fears.

We shall meet again, in Srinagar

by the gates of the Villa of Peace,

our hands blossoming into fists

till the soldiers return the keys

and disappear. Again we’ll enter

our last world, the first that vanished

in our absence from the broken city.

SANJAY KAK

New Delhi

March 2011

1Buried Evidence: Unknown, Unmarked, and Mass Graves in Indian-administered Kashmir, 2009 [http://www.kashmirprocess.org/reports/graves/toc.html].

2 http://kafila.org/2011/01/18/these-are-not-stones-these-are-my-feelings-kashmir/

3 http://www.greaterkashmir.com/news/2011/Feb/10/protesters-had-personal-problems-claims-ssp-50.asp

4 http://www.indianexpress.com/news/facebook-used-to-fuel-unrest-in-kashmir-army/745010/

5 http://www.risingkashmir.com/news/us-made-pain-gun-to-tackle-kashmir-protests-6371.aspx