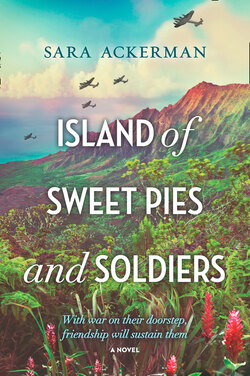

Читать книгу Island Of Sweet Pies And Soldiers - Sara Ackerman - Страница 14

ОглавлениеChapter Seven

Violet

When the shadows had lengthened and the thrushes broke into song, Setsuko and Umi showed up at the door with Ella. Violet had been checking the window every few minutes, watching for their arrival.

“Auntie Violet, your daughter is home!” they called.

She ran out to greet them. Ella walked straight to the coffee table and set down a folded red crane before coming back to hug her. The hug was double what she usually got.

“How did it go?” She eyed Setsuko, who smiled.

Waves of excitement were pouring off of Ella. “I’m going to make a bonsai, and help in the victory garden!”

Violet bent down, not wanting to tamper with her success by making too big a deal. “Well, that’s wonderful news. I’m sure they can use you with all of your gardening expertise.”

“They sing a lot, too. I don’t mind singing, but today I didn’t know the words.”

Setsuko risked a laugh. “The words will come.”

“Did you learn anything else?” Violet asked.

Ella thought about it for a while. “I learned that it’s a whole lot more fun than regular school.”

“Oh, honey, I’m happy you had a good time. You still have to go to regular school, but this will be something to look forward to.”

With Ella on the mend, their lives could take on a whole new orbit. She envisioned Ella plumping up, waking to dry sheets in the morning, not being terrified senseless by air-raid drills and letting her skin heal over. The hurts of her daughter commingled with her own, but instead of seeming double, they more than quadrupled. Certainly Violet missed Herman as a husband and the man she counted on in life, but more so she missed him as a father to Ella, as a fellow parent. Every now and then she felt guilty for having those feelings. That she should have loved him more passionately. But that was the truth, and lying to herself would serve no purpose.

* * *

On Thursday and Friday, Violet held her breath while Ella was at Japanese school, at any moment expecting to have her show up at the door. But on both days Ella returned with new stories and an extra spot of color on her cheeks.

“Today Sensei told us a story about Tanuki, and I want to get one,” Ella said, folding her hands on her chest like it had already been decided.

“A what?”

“Tah-noo-key.” Ella rolled her eyes and drew the word out as though speaking to a four-year-old. “A Japanese raccoon dog. He says they’re jolly and mischievous and some can even shape-shift into other animals.”

If Ella had it her way, they’d be collecting animals like most people collected stamps or coins. “Ask Umi to help you make an origami one for now. That’s about the best I can do.”

Their meager food rations and low wages were just enough to feed their own mouths, let alone a zoo. Sugar had been the first to be rationed and then came milk, butter, oil, meat, coffee, and other canned and processed foods. Thank goodness for their garden and those of nearby folks, with whom they often traded. Gasoline was another story. It wasn’t something you could grow. Most civilians got an A sticker, which entitled them to only three to four gallons a week, which couldn’t get you very far. Everyone stayed close to home.

* * *

When Saturday dawned a honey-colored sky, they piled into the Ford and drove up to their garden plot above town, in a place called Ahualoa. The road was steep in some places, rolling in others. Thickets of koa and smaller clusters of ohia attracted bees, and even native honeycreepers. Ella kept her eyes glued to the window, waiting to spot the tiny red birds darting from tree to tree like forest sprites.

“Honey, I’ve got a feeling we aren’t in Minnesota anymore,” Jean said.

Ella giggled. Jean wished she was Judy Garland and was the first to admit it. Ella had joined her on the bandwagon.

“You’ve never even been to Minnesota,” Violet said.

“California, then.”

On a small patch of land at the two-thousand-foot elevation, Herman had planted potato, corn, peas, cucumber and watermelon. At first Violet had shied away from anything to do with farming, after the disintegration of her family farm in Minnesota and the unraveling of her father. But here in Hawaii, there was no dust or frozen winters and everything grew with a vengeance. Over and over, in a silent mantra, Violet had reminded herself that Herman was not her father.

Violet renewed the lease after Herman’s disappearance. Some weeks, there was enough overflow that she and Jean brought bushels into town to sell.

Not only that, but Violet swore that the minute Ella stuck her hands in the dirt, whatever gave life to those plants gave life to Ella. Just add water and a touch of sun.

They rode in silence for a while, which meant Jean was stewing over something. “I want to fix those boys something special tonight. Fatten them up and keep them coming back for more,” Jean said.

Violet had to keep her eyes on the rutted road. “Even if you served Spam, they’d want to come back.”

After Zach’s call, Jean had flown around the house in a flurry, dusting cobwebs and wiping down lizard poop. Violet was more reserved about having a house full of soldiers, but maybe they would bring some cheer. It sure seemed that this group of marines was more prone to smile than the last. There had been piles of them spilling out of buses and into the bars in town. The military had made an arrangement to let them hitch rides on the school buses. Many of them looked no older than her own students, and when they stepped onto the street in their uniforms, some of them could have been playing dress-up. But these boys were about to step into the blood-seeped battlefield of the Pacific. Her heart stung for them, and their mothers back home, who no doubt had a love-hate relationship with the telephone and the mailman.

Jean slipped on her purple gardening gloves and busied herself singing “Mairzy Doats.” When the song had first come out, Violet had wondered what kind of nonsense they were singing.

“What on earth is a Mairzy Doat?” she had asked Jean.

Jean quickly set her straight. “He’s saying mares eat oats. Listen carefully.”

Sure enough, Jean was right and the song soon became one of Ella’s favorites. Now the two of them belted it out.

Jean rolled down the window, letting in a burst of lemony eucalyptus air. Even while watching the road, Violet could see Jean’s foot tapping on the floor. Her hand fidgeted with an unraveling thread on the seat.

“What?” Violet asked.

“Say, I was just thinking. Maybe you should finish off the Limburger before the boys come. Or store it at Setsuko’s for the night.”

“It took me months to get that cheese. You know that.”

The cheese had been a splurge, a comfort that reminded her of home. Jean once said it smelled like a dirty soldier’s feet. Herman had tolerated it. Barely.

Jean sighed. “Do you think the boys might have heard anything about Bud’s division? Or where they’ve sailed off to?”

“Probably, but you know what they say.”

As if on cue, Ella answered, “Loose lips sink ships.”

Jean turned around. “You don’t miss a thing, do you?”

When they arrived at the plot, Violet parked under an enormous ohia tree with sun-kissed red blossoms. She let herself out and opened Ella’s door, since the inside handle had broken off and there was no money to fix it.

The minute Ella climbed out, she pointed. “What is that?”

On the other side of the tree, a whole mess of rust-colored feathers was strewn on the ground. It reminded Violet of a feather blizzard.

Ella bolted.

“Honey, wait!”

The tree trunk blocked any view of whatever disaster had transpired. Ella’s voice was shrill. “It’s still alive. Hurry!”

Alive was a generous term, she saw when she reached the scene. Large chunks of feathers were missing, including all tail feathers, and half a wing hung limp. Violet hated for Ella to see the carnage, but as a girl growing up on a Minnesota farm, she herself had seen a whole lot worse than injured or headless chickens.

The hen squawked. “Mrs. Chicken, we’re here to save you,” Ella said.

Huddled on the bare ground, the hen cocked her head to the side and stared warily at them with one blinking eye. She ruffled what few feathers she had left and tried to settle into the dirt and leaves.

Jean stood back. “I hate to say this, but I’m not sure she can be saved.”

Ella ignored her and ran to the car for a burlap sack. “Mama, can you help me?”

Violet hesitated, knowing that once they went down this chicken-saving road, there would be no turning back. Ella would fall in love and there would be another mouth in the house, another soul to worry about. If it lived. Yet she had lost the ability to say no to her daughter. Without waiting, Ella scooped the hen up and cradled it in her arms. The injured bird hardly put up a struggle and let out a few soft clucks.

That was how they ended up with a featherless chicken.