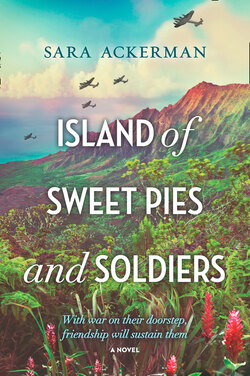

Читать книгу Island Of Sweet Pies And Soldiers - Sara Ackerman - Страница 8

ОглавлениеChapter One

Territory of Hawaii, 1944

Ella

The first soldiers arrived last December. More came last weekend. On the day the first group arrived, Mama and I were on our way to Hayashi store for a vanilla ice cream after school. Mama fanned her face and fought off rivers of sweat, but I didn’t notice the heat. Growing up in Hawaii would do that to a child, everyone always said. We were halfway down the hill when the ground began to vibrate under our feet. I thought maybe the Japanese were back, this time coming for us by land.

Mama squeezed my hand. “Honey, not to worry. The sirens would be going off.”

When we made it to the main road, we saw the first truck rolling in. In the sticky air, I could taste the diesel on my tongue. No matter what Mama said, my heart hummed along with those trucks, about one hundred beats per minute.

“That man has blood on his head,” I said, worried about a soldier leaning on the edge of the truck bed. His eyes were closed like he was in silent conversation with himself, or maybe God, and he wore a red-soaked bandage.

“Blood happens when you’re fighting a war, sweetie.”

Until that moment, I had never seen real live wounded soldiers. The soldiers were propped up against each other, looking out with blank faces. Torn shirts, bandaged limbs and eyes that had lost all smile. Folks from town rushed out to throw fruit to them. A coconut struck one man in the stomach and he slumped over. I wanted to help, but there was nothing I could do. My eyes followed him until the truck went out of sight. But even then, the funny feeling in my stomach stayed.

“Where did they come from?” I yelled above the rumble.

Mama seemed lost in her own thoughts, her big blue eyes glossy. “Hilo, probably, but before that, who knows.”

In the distance, I could see that the convoy continued on through town—past the school, the bank, the post office, following the late-afternoon sun. The last three trucks turned up the road toward Honoka’a School, where we live.

I imagined a whole new wave of war happening, and this scared the gobbledygook out of me. By now we were used to blackouts and air-raid drills. If they could so much as see the burner from your kitchen stove, you were in trouble. Big trouble, like they would arrest you and haul you off to jail, maybe forever. Saving metal scraps was also important. I used to rummage around school for any old paper clips or nails or tacks. You could turn them in for ration tickets. Rumors swirled around town, too. Hilo will be taken over soon by the Japanese. Midway is the next target. So-and-so is a Japanese spy. Everyone was affected.

“Where are they going?” I wanted to know.

Mama shrugged. “I don’t know, but we’ll find out.”

In Honoka’a, if you really wanted to know something, all you had to do was ask Miss Irene Ferreira, the telephone operator. Why was it that some people had names that had to be said together? Mama was always Violet, and Jean was Jean. But Irene was never just Irene. She swore she never listened in, and still, somehow, secrets leaked and stories spread. Even though the military took over the phones after Pearl Harbor, for some reason they let her stay on.

Once the endless line of trucks passed, we walked across the street to the small red house where she worked. Irene Ferreira sat amid wires and plugs. She wore a headset that made her look very official.

“Any idea what this convoy is about?” Mama said.

Irene pinched her plump lips together and shook her head. “Mum’s the word. You know how the military is.”

“Come on. You must have heard something.”

Irene Ferreira looked behind Mama and me, and then stood to peer outside the dusty windows. “I hear they’re building a base in Waimea town. Marines.”

Technically, Waimea wasn’t a town. It was more a ranch with a handful of wooden houses and stores sprung up around it. A cold and windy place full of Hawaiian cowboys and more grass than you’d know what to do with.

“Why our school?” Mama said.

Irene didn’t answer.

“Is there something we don’t know?”

That got my attention. If the island was filling up with soldiers, did that mean we were going to be attacked? I have my own bunny suit, which is a dumb name for a gas-mask contraption, but I never thought I would really need it. My breath caught halfway up my throat and my chest started squeezing in. This happens a lot. Vexation, Mama says. Besides not knowing how to breathe, I gnaw my fingernails to the point where they bleed and I pick at freckles and turn them into scabs. The worst of all is the stomachache that never goes away. It all started happening when Papa disappeared.

Irene said, “That’s all I know. I promise.”

As tempting as it was to stay and pry the information out of her, we decided to follow the trucks up to the school. The soldiers drove straight onto the newly clipped field in front of the gym, their heavy trucks sinking into the mud. Mr. Nakata, the principal, must have been mad, watching from the side of the gym. A man in a green uniform spotted us approaching and marched right over.

“Excuse me, ma’am. This area is off-limits,” he said.

“We live here,” Mama said, pointing toward our house.

“You don’t live in the gym, do you? Please step away.”

There was nothing Mama hated worse than being ordered around, especially by a newcomer. I sometimes point out that she was once a newcomer—here they call them malihini—but she believes it’s more about how you behave and what’s in your heart than where you come from.

Still curious, she dragged me over to the administration building, where the men unrolled strands of barbed wire and posts. Another group unloaded cots and stacks of green metal boxes. With no spare movements, they went about their business of taking over a part of our school. The war had finally arrived in our own backyard.

But for Mama and me, the war was not the worst thing that had happened lately. The worst had already come.