Читать книгу For the Wild - Sarah M. Pike - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

For All the Wild Hearts

In July 2000, federal agents raided an environmental action camp in Mt. Hood National Forest that was established to protect old-growth forests and their inhabitants, including endangered species, from logging. High above the forest floor, activists had constructed a platform made of rope and plywood where several of them swung from hammocks. Seventeen-year-old Emma Murphy-Ellis held off law enforcement teams for almost eight hours by placing a noose around her neck and threatening to hang herself if they came too close.1 Murphy-Ellis, going by her forest name Usnea, explained her motivation in the following way: “I state without fear—but with the hope of rallying our collective courage—that I support radical actions. I support tools like industrial sabotage, monkey-wrenching machinery and strategic arson. The Earth’s situation is dire. If other methods are not enough, we must not allow concerns about property rights to stop us from protecting the land, sea and air.”2 Murphy-Ellis speaks for most radical activists who are ready to put their bodies on the line to defend trees or animals, other lives that they value as much as their own.3

For the Wild is a study of radical environmental and animal rights activism in late twentieth- and early twenty-first-century America. I set out to explore how teenagers like Murphy-Ellis become committed to forests and animals as worthy of protection and personal sacrifice. I wanted to find out how nature becomes sacred to them, how animals, trees, and mountains come to be what is important and worth sacrificing for. This work is about the paths young activists find themselves following, in tree-sits and road blockades to protect old-growth forests and endangered bird species, or breaking into fur farms at night to release hundreds of mink from cages. These young people join loosely organized, leaderless groups like Earth First! and the Animal Liberation Front (ALF), coming to protests from contexts as different as significant childhood experiences in nature and the hardcore punk rock music scene. Various other experiences also spark their commitments, such as viewing a documentary about baby seal hunts or witnessing a grove of woods they loved being turned into a parking lot. What their paths to activism have in common is the growing recognition of a world shared with other, equally valuable beings, and a determined certainty that they have a duty to these others.

In their accounts of becoming activists, emotions play an important role in shaping their commitments. Love for other-than-human species, compassion for their suffering, anger about the impact of contemporary human lifestyles on the lives of nonhuman species, and grief over the degradation of ecosystems—each of these emotions are expressed through and emerge out of what I describe as protest rites. This is a study of how radical activists make and remake themselves into activists through protests and other ritualized activities. It is at the sites of protests that activists’ inner histories composed of memories, places, beings, and emotions come together with social movements such as environmentalism, feminism, anticapitalism, and anarchism, to provide these young people with the raw material out of which they fashion activist identities and communities. For the Wild is concerned with fundamental questions about human identity construction in relation to others, human and nonhuman. It investigates the role of childhood experience and memory in adult identity and the contours and meanings of our multiple relationships with the more-than-human world. It attempts to understand the connections between individual worldviews, collective ritual, and social change. I explore what the case of radical activists tells us more generally about memory, ritual, commitment, and human behavior, about how the lives of other-than-human beings come to matter, and especially about young adult behavior, since most activists first become involved with activism during their teenage years or early twenties.

Radical activists may be living out their most deeply held commitments, becoming heroes to each other in the process, but to outsiders they are often seen as “eco-terrorists.”4 Cable Network News reported in 2005 that in the view of John Lewis, an FBI deputy assistant director and top official in charge of domestic terrorism, “The No. 1 domestic terrorism threat is the eco-terrorism, animal-rights movement.”5 A few years earlier, Rolling Stone reported that FBI director Louis Freeh testified before a Senate subcommittee that “the most recognizable single-issue terrorists at the present time are those involved in the violent animal-rights, anti-abortion and environmental-protection movements.”6 According to the FBI, groups like the ALF and the Earth Liberation Front (ELF) have “committed more than 1100 criminal acts causing more than $100 million in damage.”7 Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, environmental and animal rights activists have been aggressively pursued by the FBI, as journalist Will Potter illustrates in his account of the persecution of “eco-terrorists,” Green Is the New Red.8 In 2005 the federal government made highly publicized arrests in what FBI agents dubbed “Operation Backfire,” the largest round-up of eco-activists in American history. Two years later, ten defendants were convicted on federal arson and vandalism charges, receiving sentences ranging from three to thirteen years. Although no one was hurt or killed in any of the acts, federal prosecutors had argued for life sentences. Even with the threat of prison time, after Operation Backfire radical environmentalists and animal rights activists continued to operate both clandestinely and through aboveground protests. The two movements increasingly converged during the second decade of the twenty-first century. However, the primary focus of this book is on the second half of the 1990s and the early 2000s, when those activists who received significant prison sentences were participating in direct actions in the United States.

For the Wild considers the following questions: How do young people become activists in a network of relationships with trees, other activists, nonhuman animals, and landscapes, acted on by and acting upon different agencies, human and other-than-human? What are the most central emotional and other kinds of experiences from childhood and young adulthood that inspire extreme commitments and shape protest practices? What idealized and desired relations between human and nonhuman bodies are implicated in and emerge from protests? What forms of gender and ethnic identity are contested, deployed, constructed, and negotiated during ritualized actions involved with protests, and what kinds of fractures and conflicts within activist communities are revealed? What bearing do activist protests on behalf of the environment have on social and political change or new forms of democracy in terms of spatial practices and decision-making structures? How do activists express and deal with the grief and loss that accompany environmental devastation and climate change? In order to address these and other questions about radical environmentalism and animal rights, I focus on the role of childhood experience, youth culture, embodied ritual actions, and the emotions of wonder, love, anger, compassion, and grief.

SCHOLARLY CONTEXT AND BACKGROUND

My study is situated at the intersection of a number of disciplinary fields, including religious studies, environmental studies, cultural anthropology, ritual studies, critical animal studies, and youth subculture studies. For the Wild is very much an account of youth, a stage of life after childhood that extends through the early twenties.9 Young people are often disregarded in scholarship on religion and spirituality, even though teenage and young adult years are formative in shaping spiritualities and worldviews.10 The intersection of youth culture, religion/spirituality, and activism has been particularly neglected by scholars, including by cultural studies research on youth subcultures.11 Moreover, the small body of work on teenagers and religion is almost completely focused on Abrahamic religions, particularly Christianity, and rarely includes religious experiences of the natural world or beliefs about animals and the environment.12 My emphasis is on the ways in which spiritual orientations and experiences are intertwined with other shaping factors as young adults come to believe that they must put their lives on the line for nonhuman animals and the natural world.

It is particularly interesting that spiritual aspects of these movements have been ignored, since many representations of activists by the news media and law enforcement focus on their moral lack. Activists do feel a lack, but it is not the absence of morality. Spring, an activist I met at an environmentalist gathering in Pennsylvania, touched her chest and told me, “I always felt an emptiness . . . because the earth is being destroyed and I needed to work to do something.” Part of the problem, she explained, is that our society “denies our spiritual connection to the earth.”13 In depictions of activists as terrorists, they are shown to be morally deficient, when in fact it is deep spiritual connections and moral commitments that result in actions that sometimes land them in prison.

This study is ethnographic in nature, but also informed by other types of approaches that focus on how environmental and nonhuman animal issues are entangled with human ways of being in the world. These different disciplinary orientations help me address the ways in which activist youth come to express and practice their spiritual and moral commitments through rites of protest against environmental devastation and animal suffering. My work draws heavily on recent trends in anthropology, environmental humanities, and science studies that suggest new ways of thinking about relationships with other species as well as with the material world.14 I have been helped by revised understandings of animism, the new materialism, and other approaches that decenter the human and work on the boundary (or lack thereof) between human and other-than-human lives.15 Like activists, these scholarly approaches challenge strict distinctions between the human and the larger-than human world. They ask how we should think about our relationship to other species and landscapes when we share so much of our lives and even our very cells and selves with them. Our bodies and identities are not easily distinguished from those of others, even matter as inanimate as the rocky assemblages and mountains some of us call home.16 How we come into being and who we identify as a person or significant presence in the world are processes that take place in particular cultural and historical contexts.

In addition to twenty-first-century developments, there are ancient examples of ways in which humans come into being in a world of relationships with other-than-human beings and landscapes. Aspects of Asian traditions such as Taoism and Confucianism, as well as many indigenous worldviews, express similar orientations towards human entanglement in and inextricability from the more-than-human world.17 Many activists are informed by and/or borrow from these traditions.

In the opening decades of the twenty-first century, views of our responsibility for and entangled relationships with species and landscapes have even been expressed in the political realm, such as through movements to bestow legal rights on nature. In 2008 Ecuador became the first country to include the rights of nature in its constitution. These rights include the following: “Rights for Nature. Rather than treating nature as property under the law, Rights for Nature articles acknowledge that nature in all its life forms has the right to exist, persist, maintain and regenerate its vital cycles. And we—the people—have the legal authority to enforce these rights on behalf of ecosystems. The ecosystem itself can be named as the defendant.”18 In a similar fashion, in the global North, science studies scholar Bruno Latour and other scholars, students, and artists prepared for the 2015 Paris climate talks by creating an event at a Paris theatre called “Paris Climat 2015 Make It Work/Theatre of Negotiations” in which natural entities like “soil” and “ocean” were given representation and “territorial connections” were emphasized over nation-states. During the event, nonspeaking entities from fish to trees to the polar regions were spoken for and included in negotiations around climate and geopolitics.19 Like radical environmental and animal rights activism, these efforts might be seen as a ritualized politics of the Anthropocene. They are responding to widespread recognition that human reshaping of the planet and its systems through nuclear tests, plastics, and domesticated animals, among many other examples, has been so profound that we have entered a now geological epoch.20

Like the Ecuador constitution and participants in the Theatre of Negotiations, animal rights and environmental activists speak for natural entities. Activist bodies and identities emerge within specific kinds of relationships with other beings in a variety of complex ways that lead activists to protests. For this reason, I want to emphasize activists’ “becoming with” other-than-human beings, both intimate and distant. I approach young adults’ transformation into activists as a biosocial becoming, to borrow a term from anthropologists Tim Ingold and Gisli Palsson, a process in which activists should not be understood as clearly bounded “beings but as becomings” in relationship to many other beings.21 Science studies scholar Donna Haraway’s view of co-becoming also emphasizes the complex and dynamic ways we relate to other species and the life we share with them, even at a cellular level, because human nature is fundamentally “an interspecies relationship.”22 Activist identities emerge from their interactions with many species and landscapes through childhood and young adulthood, as they become human with these others over time, reactivating themselves, so to speak, as they relate to trees, nonhuman animals, and landscapes where they find themselves at protests. It is through these ongoing relationships that they come to know these others’ pain and suffering as their own, that they come to fight “for the wild” and “for the animals,” as they often sign letters and press releases.

For many activists, caring arises from encounters with an objective reality of suffering and devastation that they experience in the world, an encounter with a mink in a cage or what is left of a mountain after its top has been removed to get at the coal inside. Encounters with humans affected by devastation play a part too in moving them towards action. For anti–mountaintop removal activists such as RAMPS (Radical Action for Mountains’ and People’s Survival), for example, the faces of people in poor communities affected by polluted water are as important as ruined mountains plowed over for the coal beneath them.23 For these beings and places, activists must act; they have no other choice. Theirs is a politics of intimacy with these others that emerges from direct encounters with a living, multispecies world. For the Wild uncovers and explores the deep experiential roots of activists’ political commitments as a reaction to the profound reconfiguration of planet Earth and its beings by industrialized civilizations.

My exploration of the role of ritual and emotion in the commitments of radical activists pushes towards a broader understanding of the stream of American thought and practice historian Catherine Albanese has called “nature religion.”24 Like many of the examples Albanese discusses, activists are more interested in this-worldly than otherworldly concerns, or as activist Josh Harper put it when explaining his disinterest in religion: “this world is primary.”25 They are likely to say they are agnostic or atheist, yet approach activism as a sacred duty, putting into practice a nonanthropocentric morality. Animals and the natural world are what they care about most, although they link environmental and animal issues to struggles for social justice.

As a study of spiritually informed activism, among other things, this book investigates activists’ lived experience of nature and nonhuman animals as central to their worlds of meaning. I draw especially on Robert Orsi’s definition of religion as “a network of relationships between heaven and earth involving humans of all ages and many different sacred figures together.”26 In what follows, I will suggest some of the ways that radical activists make special, and even sacred, relationships between human and nonhuman earthly others, including not only nonhuman animals and trees but also other activists who have become comrades and martyrs in a holy crusade to save the wild. While some activists may see the Earth’s body as Gaia or trees as gods and goddesses, they are more likely to emphasize the sacred relationships we have with other species and the sacred duties and responsibilities we consequently owe them. Trees and nonhuman animals, or even the Earth itself in a more abstract sense, are regarded by activists with awe and reverence. And what these activists set apart from the sacred as profane are the human actions and machines that threaten these beings and places. In the context of activism, “sacred”—a sacred crusade to save the wild or the sacredness of a forest—designates those for whom activists will sacrifice their own comfort and safety.27 These beings and special places are worth the discomfort of many days in tree-sits and the risk of long prison sentences. It is the meanings and origins of these sacred relationships and duties that I focus on in this work.

A number of activists told me they do not like the term activist for various reasons, but I have chosen to retain it because I am most interested in actions that express their commitments and desires. This study is practice centered and focuses on what activists do and how they came to do it, as well as the beliefs behind their actions. For the purposes of this book, I define radical activists as those who reject anthropocentrism and speciesism and practice direct action.28 Through direct action they challenge assumptions about human exceptionalism and boundaries between species used to exclude nonhuman species from moral consideration. They also think of themselves as “radicals” in ways I will explore at length, but that include identification with anarchism and the strategies and beliefs of earlier radical movements like the Black Panthers and gay rights. Animal rights activists and radical environmentalists are also closely affiliated with contemporary anticapitalism radicals, such as the Occupy movement. For some radical environmentalists such as Earth First!ers, being radical is about getting to the roots of environmental destruction: our very ways of thinking and acting as human beings on a planet where we coexist with many other species.29 Being radical separates these activists from more mainstream environmental groups—the Sierra Club, for example—and animal rights organization such as the Humane Society (HSUSA). They critically point to the compromises made by mainstream environmental and animal rights organizations and highlight their own refusal to compromise. They engage in direct action and promote an “every tool in the toolbox” approach to environmental and animal issues. Such a toolbox includes illegal acts of property destruction such as arson, occupation of corporate offices, sabotage of machinery, and animal releases, differentiating them from organizations that eschew illegal and confrontational tactics. The refusal to compromise is a hallmark of radical commitment: if eco-activism is a sacred crusade for the wild and for the animals, ideally, then, nothing should prevent activists from acting for them.

THE ROOTS OF RADICAL ACTIVISM

Late twentieth- and early twenty-first-century radical animal rights and environmental activism’s origins are complex, the background of participants is diverse, and the two movements have somewhat different genealogies that I trace in more detail in Chapter 2. Radical environmentalism draws on seven main sources that have contributed to expressions of activism seen in Earth First! and the ELF:

1.What historian Catherine L. Albanese has described as “nature religion”: ideas and practices as diverse as those of Native Americans and New England Transcendentalists like Emerson and Thoreau, that make nature their “symbolic center.”30 Religious studies scholar Bron Taylor further specifies a strain of American nature religion that he calls “dark green religion,” that includes radical environmentalists and is characterized by adherence to the view that “nature is sacred, has intrinsic value, and is therefore due reverent care.”31 Taylor discusses the nature religion of radical environmentalists in a number of articles where he argues among other things that ecotage itself is “ritual worship.”32 This view is shared by sociologist Rik Scarce, who characterizes tree-sitting as a “quasi-religious act of devotion.”33 Historical studies by Evan Berry and Mark R. Stoll broaden this tradition of nature religion by suggesting that nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century American environmentalism was shaped in important ways by Protestant forms of Christianity.34

2.The secular environmentalist movement that emerged in the 1960s, built on earlier activities, and was expressed in initiatives such as the Wilderness Act (1964) and Earth Day (1970).35

3.Deep ecological views, particularly the work of Arne Naess, Bill Devall, and George Sessions, that have shaped and been shaped by nature religion and the environmental movement. Norwegian philosopher and mountaineer Naess coined the term “deep ecology” in 1973, as a contrast to the “shallow” ecology movement. Deep ecologists promote an ecological self and eco-centric rather than anthropocentric values.36

4.The fourth source is a related set of social and political movements that also emerged out of and were significantly shaped by the 1960s counterculture and include the antiwar movement, feminism, and gay rights, as well as environmentalism.37

5.Contemporary Paganism/Neopaganism. While many activists do not consider themselves religious or Pagan, nevertheless, contemporary Paganism had a significant influence in the 1980s and 1990s on forest activism in the Western United States, and on important activist organizations like Earth First!38

6.Indigenous cultures. Activists are also influenced by their understanding of Native Americans’ relationships to other species. However, they tend to be sensitive about appropriating these views for their own use in fear of perpetuating European colonialism and a mentality characteristic of “settlers” who are not indigenous to North America. Activists’ appropriation of indigenous beliefs and practices as well as their desire to support indigenous people’s struggles has been a significant but contested subject in the history of radical environmentalism, which I discuss at length in Chapter 6.39

7.Anarchism, especially global anticapitalist movements like Occupy Wall Street and green anarchism, or anarcho-primitivism, especially the writings of John Zerzan, Derrick Jensen, and Kevin Tucker.40

Radical animal rights activism developed in the United States alongside radical environmentalism. Both movements emphasize direct action, criticize speciesism and anthropocentrism, often link their concerns to social justice struggles, and situate themselves within a lineage of radicalism. While many animal rights activists have also been influenced by deep ecology and some by contemporary Paganism, radical animal rights in the 1990s and 2000s was more significantly shaped by anarchism and the hardcore punk rock subculture, especially a movement called straightedge that I explore in detail in Chapter 5. Radical animal rights activism is also one of many expressions of shifting changes in understandings of the relationships between human and nonhuman animals in the United States and in the global North in general, which I discuss in Chapter 2.

SOURCES AND METHODS

For the Wild is informed by multiple methods, but most centrally by ethnographic fieldwork. I have supplemented ethnographic research with a variety of other sources of information about activists’ experiences and commitments. I base my exploration of radical animal rights and environmentalism on several kinds of primary sources. The first is written, emailed, or in-person correspondence and interviews with environmental and animal rights activists, including those serving prison sentences during our correspondence. Some of them were organizers for activist groups or gatherings, including the Buffalo Field Campaign, North Coast Earth First!, Earth First! Rendezvous, the Animal Rights conference, and the North American Animal Liberation Press Office. I also conducted informal and recorded interviews with a number of activists, either during gatherings (never recorded), at coffee shops and restaurants (usually recorded), and at the Earth First! Journal collective (recorded).

I supplemented correspondence and interviews with participant-observation at five gatherings, some of which featured direct actions, including the annual Earth First! Round River Rendezvous, which I attended in 2009 (Oregon), 2012 (Pennsylvania), and 2013 (North Carolina); Wild Roots, Feral Futures in 2013 (Colorado); the Trans and Womyn’s Action Camp 2014 (TWAC, California); and the Animal Rights conference in 2009 (Los Angeles). These gatherings, usually held annually, are primarily for sharing information and experiences, creating community, getting various kinds of training, and airing conflicts. The Earth First! Rendezvous and TWAC gatherings usually include preparing for and engaging in direct actions, such as blocking a road to a hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) site. In each instance I contacted the organizers in advance, explained my project and let them know that I would not be making any recordings, visual or audio, during the gatherings, because anonymity and privacy are important to activists. I have used pseudonyms or “forest names” for my interlocutors, depending on their preference and have disguised other identifying features. In the case of well-known activists, such as those who have served prison sentences, I have usually retained their real names so as to be consistent when discussing references to them in the news media and elsewhere. I did not interview or contact any minors; instead, I focused on young adults’ reflections on their teenage years.

I participated in all aspects of activist gatherings: I used gathering ride boards to find riders to travel with me to gatherings, ate meals in the communal dining areas, prepared food, washed dishes, went through a street medic training, volunteered in the medic tent, learned how to climb trees, went to workshops and direct action trainings, learned chants for protests, and held signs and sang chants at protests.

As a participant and observer I often struggled to balance my two roles. In many ways I blended in with activists in terms of my values and interests. I consider myself an environmentalist who travels by bicycle as much as possible, who does not own a dryer, who composts, reuses, and recycles. As a long-time vegetarian, vegan food and arguments for veganism and vegetarianism were familiar to me. My own story intersects with the stories of activists at a number of other junctures as well. At nineteen, while in college, I became involved with nonviolent direct action during the antinuclear movement of the late 1970s, participating in antinuclear collectives and protests in Kentucky and North Carolina. During those years I was introduced to some of the practices used by contemporary environmental and animal rights organizations, such as nonviolent direct action, talking circles, consensus decision making, and affinity groups. In the early 1980s, I spent many hours at punk rock and hardcore shows. A few years later I entered graduate school, earning a doctorate in religious studies at Indiana University, Bloomington, where I also minored in women’s studies and taught in I. U.’s Women’s Studies program while finishing my dissertation on contemporary Pagan festivals. In these and other ways, I was involved with practices, movements, and ideas that shaped radical environmentalism and animal rights activism a generation later.

On the other hand, I was an outsider at activist gatherings, not currently working on a direct action campaign and over twenty years older than the majority of participants. I did not blend in. There were activists around my age, but not many, and some participants probably suspected I was spying on them, even though it is unlikely someone trying to gather intelligence on activists would look like me. Informants such as “Anna,” a twenty-one-year-old FBI agent who infiltrated an ELF collective, do their best to blend into the crowd, which I did not. My visibility as an outsider was both an asset and a liability. I was not privy to some of the more secretive conversations, especially involving actions, and thus missed out on negotiations and concerns at that level of involvement. On the other hand, being treated a bit suspiciously worked in my favor in that I was less likely to be told about anything illegal. I made it a point not to ask about underground actions, only those actions activists had already been sentenced for or that were public, above-ground, and covered by the news media. All of these experiences had a profound influence on how I related to what I heard and saw during my research and have contributed to how I have written this story about radical activism.

My age and life experience turned out to be useful. Because of a stint working in restaurants as a young adult, I could easily follow directions and make myself useful in community kitchens at gatherings. Given years of dealing with a variety of classroom dynamics, I handled situations that required a calm demeanor, such as helping in the medic tent or filling in as a police liaison when the assigned liaison was needed elsewhere during an action. No doubt the police treated me differently as well. As I became more familiar to the communities by participating in all aspects of the gatherings, most activists eventually seemed to accept my presence. They were open with me in as many ways as they were suspicious of me, and many of them shared details of their lives, explaining what mattered to them and why in ways I could understand.

For the Wild is very much the result of intersubjective understandings that emerged from my conversations with activists and from the interfaces of my sensory, embedded experiences with activist communities. You will read my view of what emerged from our conversations, checked against other sources and other views. Any attempt at objectivity would be fragile and incomplete, and mine is no objective portrait of activism, although I try to fairly represent multiple views on most issues. No doubt activists would tell some of these stories differently. But their narratives would be multiple and varied too. Like me, many of them moved in and out of campaigns, returning to work and school in between, while others remained full-time activists. Some of those I spoke with had only been involved for a few months or were attending a protest for the first time, while others drew from many years of experience on campaigns to save wild places and nonhuman animals. There is no central organization in the anarchistic groups I learned from and participated in, no authority to turn to for an official interpretation. Meaning and authority in these movements emerge from what is happening on the ground, between people, in concert with landscapes and other species, and in essays about movement strategies and practices online and in print.

In addition to interviews and participant observation, I draw on three different kinds of primary print sources: published memoirs by environmental and animal rights activists, such as Paul Watson’s Seal Wars; print publications such as the Earth First! Journal and Satya: Vegetarianism, Animal Advocacy, Social Justice, Environmentalism; and self-published, photocopied, and usually anonymous “zines” that I picked up at gatherings. These zines ranged from reprints of activist publications to self-authored essays such as those collected in the zine Reclaim, Rewild: A Vision for Going Feral & Actualizing Our Wildest Dreams. The final type of primary source was online documentation of actions and gatherings, including photographs, videos, and written accounts of actions and news stories on activist websites, particularly the Earth First! Newswire.41

Activists whom I met at gatherings or whose articles I read in print and online are incredibly diverse and difficult to generalize about. While there are well-known figures in these movements, such as Earth First! founder Dave Foreman or PETA founder Ingrid Newkirk, they are as likely to be criticized as emulated. Renowned activists like Jeff Luers and Marius Mason (formerly Marie), who served time in prison, were often referred to with awe and respect by other activists I met. But the communities I spent time with are leaderless; they have policies (such as nonoppressive behavior) that participants mostly agree on, but no central organization. In what follows, I describe and analyze important trends and common views and experiences. While my observations will not fit every activist, it is my hope that activists will recognize their communities as I have depicted them and that I have accurately captured many of the values and experiences they share.

From the distro table: zines.

In my journey through the worlds of activists, two concepts have particularly troubled me: “nature” and “the wild.” I try to use these words in the ways activists use them. But “nature” and “the wild” are, of course, constructions situated within a particular set of late modern conditions, including nostalgia for an imagined past in which humans lived more harmoniously with other species. “Nature” might be seen to include toxic chemicals and clearcuts as well as human beings, even human beings who have no respect for other species, but obviously this is not what activists mean when they refer to “nature.” When activists say they want to protect nature or are “for the wild” and “for the animals,” they mean they want to protect trees, animals, and relatively wild places from human interference to the greatest extent possible. Sometimes this means making animal testing illegal, getting an area designated as wilderness, or halting logging in old-growth forests and areas inhabited by endangered species. Of course imagining forests or any wild landscape as a place of human absence, a place apart from culture, also depends on erasing the cultures that dwelt and sometimes now dwell there. Some activists have a more sophisticated understanding of history than others; they know that Native Americans managed forests and grasslands, that the “wild” as we understand it in contemporary North America has been made over by humans for millennia. Others see our encroachment as more recent. But in both cases the “most important thing we can do,” according to Rabbit, an editor at the Earth First! Journal, is “protecting what we have left that is wild . . . and trying to rewild the rest . . . The world without so much human involvement had worked for a long time.”42

In addition to extending rights and protection to other species and wilderness areas, many activists emphasize human animality and the need for us to “rewild” our lives, in order to become more feral than civilized. “Nature” and “the wild” then, tend to mean places and states of being that are not domesticated, not controlled by humans, and usually set in opposition to industrialized “civilization,” an opposition that I describe and analyze throughout the following chapters. Rewilding of the human self in a community of other species is a personal transformation that mirrors the transformation of ecosystems by rewilding and reverses domestication. Such transformations come about through particular kinds of embodied practices and experiences, often ritualized.

RITES OF CONVERSION AND PROTEST

I turn to ritual as another perspective on activism.43 In order to best understand how activists express their commitment to the wild, the tools of ritual studies have been particularly helpful to me. For the Wild is about two kinds of ritual: conversion as a rite of passage or initiation into activism and protests as ritualized actions. Conversion tends to take place on an internal and personal level, while protests are usually participatory and collective. In the context of conversion to activism, I explore the ways in which the love, wonder, rage, and grief that motivate radical activists develop through powerful, embodied relationships with nonhuman beings. Conversion to activism can happen in a matter of moments, during what some activists describe as a tipping point, or it can be a longer, more subtle internal process of shifting one’s worldview.44 It may happen within a protest setting such as a tree-sit or road blockade, when listening to vegan hardcore punk rock, as a result of the death of a nonhuman animal friend, or while watching a video about seal slaughter, to name some of the examples described in this book.

Protests like tree-sits and animal liberations are ritualized actions or events. In this study I understand ritual as a distinctive way of enacting and constituting relationships among humans, as well as between humans and other-than-human beings (animals, trees, etc.) or “nature” writ large.45 Protests call into question destructive relationships between humans and other species. They also suggest new kinds of relationships between humans and the others with whom we are entangled on this earth. Our human situatedness in terms of gender, class, ethnic background, age, and ability also shapes the kinds of relationality we experience with other beings, human and other-than-human. The relationships that are expressed in and emerge from protests challenge human superiority as well as lines dividing us from other species. Protests create and express particular kinds of bonds among activists (such as bonds of love and solidarity or bonds of animosity and difference) as well as between activists and loggers, construction workers, animal researchers, and law enforcement. These latter are often but by no means always oppositional. In these ways, protests express and create a world of interrelated life forms, co-shaping each other. What emerges during protests is a larger-than-human world brimming with diverse forms of life and full of meanings and spirit, a world composed of relationships between many different kinds of humans, various species, bodies of water, rocky assemblages, and landscapes.

Environmental and animal rights protests feature at least some of the following aspects: (1) a particular focus, orientation, and/or way of participating; (2) a reconfiguration of space; (3) the danger or vulnerability of participants; (4) an enactment of particular realities and ideals; and (5) experiences of both collective solidarity and tension/conflict.46 I wanted to explore a range of environmental protests in order to think through what happens in protest rituals and what theoretical tools might help us understand the ways rituals constitute social relationships and bring about or do not bring about change, such as legal protections for wild places or nonhuman animals. What kinds of boundaries are called into question by particular protest rituals? What boundary crossing takes place in the ritual space? What or who is transformed when boundaries are crossed? How are boundaries we all take for granted dissolved? Will that dissolution continue after the ritual protest, and how will that dissolution manifest?

Protests involve a number of intentional actions and specific modes of participation that carry special meaning within the context of activism. These may include playful practices such as “radical cheerleading” in which chants and dance moves are focused on the issues at hand, such as fracking or coal mining. Other modes of participation might be climbing trainings held before or during tree-sits to teach techniques of the body and skills that require a specific focus on the danger and meaning of climbing in an event. Recreation is not the reason activists learn chants or how to safely climb trees; theirs is a different focus and mode of interaction in relation to these activities. While it may be challenging or enjoyable, activist climbing is about climbers’ intentions, about getting into a tree or onto a building to drop a banner in order to disrupt or prevent logging, mining, road building, and so on. Activist medic trainings include learning how to flush out protesters’ eyes after they have been pepper sprayed. Confrontations with law enforcement officers are rehearsed in order to defuse potential violence and avoid being triggered into reacting violently. Before and during protests, these practices happen within specially focused spaces. While some of them may be continuous with everyday activities such as climbing trees for fun or working in a hospital, they carry particular meanings at activist gatherings and events. Ritualized actions within specific spatial and temporal contexts negotiate and express activists’ orientation to the world and relationships with many other beings.

Protest actions usually involve reconfiguring space. This can include actions such as overturning a van to which activists lock themselves in order to block a logging road or building a tree village with platforms and ropes in a grove of trees to prevent trees from being bulldozed for a natural gas pipeline or a new highway. This reconfiguring may even involve the destruction of certain kinds of spaces, such as an ELF action against a wild horse corral that involved both the release of horses and the burning down of the corral. In these cases, what activists change constitutes another way of being in relation to the logging road (resisting its use by logging machinery) and to the horses (preventing their captivity rather than supporting it).

During such protests, activists’ pain and sacrifice may play an important role, just as the suffering and pain of nonhuman others shape activists’ commitments. Activists put themselves in danger, committing acts of arson that could carry lengthy prison sentences, splaying their bodies on the ground in front of bulldozers, or hanging precariously from redwood canopies. These ritualized actions are intended to challenge assumptions about what and who is of value. Most forest actions that try to delay logging and draw attention to endangered old-growth forests involve positioning human bodies between loggers and trees, so that logging cannot occur without hurting or killing activists. Some animal rights actions involve risky night-time exploits to free animals from locked and guarded research facilities.

These protests work in part because of the risks protesters take, what communications scholar Kevin DeLuca calls their “utter vulnerability.”47 Risky protest tactics heighten suspense and increase the identification between activists and those on whose behalf they are acting. These protests are ritualized interventions, ruptures that rearrange the taken-for-granted order of society by placing value on the lives of redwood trees and spotted owls and by risking one’s own body for these other bodies. In this way, the danger and precarity involved in protests enact activist ideals, including a reality in which the more-than-human living world is valued and protected, even at the cost of human flourishing. Activists’ precarious protesting bodies also remind viewers of the vulnerable species they identify with.

Protest rites continually remake activist identities that come about through conversion to a set of commitments. In his classic study of adolescence, Erik Erikson observed that identity formation is the primary task of adolescence. Young people must forge a sense of self that will eventually allow them to leave their families. These new selves are formed in a liminal space, a space of transformation according to Victor Turner’s, Arnold van Gennep’s, and more recently, Ronald Grimes’s research on rites of passage. Drawing on van Gennep, Grimes argues that rites of passage are “pivots, at which one’s life trajectory veers, changing direction.” These pivots, observes Grimes, “are moments of intense energy and danger, and ritual is the primary means of negotiating the rapids.”48 Activists’ lives pivot in this way during intense and dangerous protests that inscribe identities on their bodies.

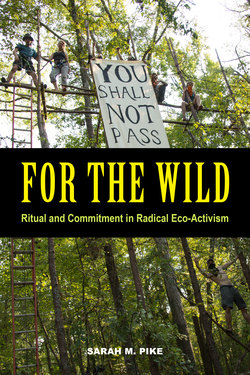

Earth First! Elliott Forest blockade bipod. Photo: Margaret Killjoy. Licensed under Creative Commons 2.0.

In many cultures there are clearly defined steps that bound adolescent liminality, but in contemporary American culture, these bounds are anything but clear. As Grimes puts it, “we know so few authentic and compelling rites,” that adolescent rites of passage in the West often take a “postmodern, peer-driven form” that can be vague or uncertain.49 But for many activists, there is nothing vague about the life-changing transformations they undergo when they become committed to activism. Their initiation into activism is an irreversible change that effectively divides their lives into a “before” and “after,” a common feature of initiation rites.50 While I use “conversion” and “initiation” interchangeably here, initiation might be seen as more of a public process during which a community of others, human and nonhuman, work on activists’ lives. On the other hand, conversion is more of an internal process during which the shaping forces of human and nonhuman others are taken “deeply into the bone,” to borrow Grimes’s phrase.

Activists’ accounts of how they became committed to activism tend to fall into two categories. For some, becoming an activist was a gradual process of being more true to themselves, confirming what they had always believed. For others, activism marked a critical point in their lives when they rejected many aspects of their upbringing or social status and chose activism. Both types of conversion involve a before and after, and different understandings of self-identity. The activist self is either completely different, or a new version of someone who was “always there.” Throughout this book, I discuss both processes in detail, drawing attention to the different forces working on youth as they become activists. During their young adult years, activists-in-the-making do not become successfully socialized into what they describe as capitalist, anthropocentric American society. Instead, they experience conversion to a contrasting set of values and beliefs that shape their activist commitments. They reject many aspects of the culture around them in favor of anarchism, animal rights, and environmentalist commitments and they choose to break human laws in favor of what they consider a higher morality. I argue that their developing commitments to activism are a kind of internal revolution that marks a conversion to or initiation into activism.51

Rites of passage into activism are not entirely dissimilar to the rites activists have rejected from their pasts and criticized in the broader society. Activist conversion stories may incorporate the language of conversion common to some forms of Christianity, such as being “baptized” or “born again.” Accounts of how they became committed to radical activism suggest that they express their conversion through the ritualized actions involved with protests.52 Although activists typically move away from Western religious traditions, conversion to activism nevertheless sometimes includes the return and reincorporation of the language of Christian rites of passage such as “baptism,” even when there are no accompanying ritual actions such as immersion. American Evangelicals are more typically identified with the born-again experience, but activists who reject Christianity redefine being born again in an unexpected context in which nature and animals, rather than God, become the sacred centers of their lives. Being born again as activists is a fundamental reorientation of meaning in which the lives of other-than-human beings come to be as valuable as their own.

The notion of a second chance or new life after conversion in which one’s old ways are left behind is such a pervasive metaphor in American cultural history and American religion that it lends clout to conversion stories. At the animal rights conference in Los Angeles I attended in 2007, plenary speaker Alex Pacheco, one of the founders of PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals), told the audience that he was “baptized” into animal rights through his involvement with Paul Watson and Sea Shepherd (a direct action organization of activists formed to protect marine mammals and featured in the series Whale Wars that premiered in 2008 on cable station Animal Planet). He went on to describe his “second baptism” working with the underground ALF as a further stage in his initiation into activism. Another participant in the Los Angeles conference, who said she grew up as a “born-again Christian” and later left Christianity, also described being “born again” into the animal rights movement as beginning a new phase of her life.53 In various sessions and workshops, other conference-goers identified a “tipping point” that set them moving towards their commitment to nonhuman animals, often the final stage in a series of experiences that had already prepared them for such a commitment.

These activists, while painted as extremists, might also be seen as expressing concerns that cut across a broader swathe of the U.S. populace. Activism is one of many possible ways that young Americans, who experienced the greatest growth in the category of “spiritual but not religious” or “unaffiliated” in the early twentieth century, express spiritual and moral values outside religious institutions in unexpected places.54 The widespread and surprising support among American youth for Bernie Sanders’s campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2015–2016 speaks to young people’s dissatisfaction with the social and political status quo, including attitudes toward the more-than-human world. For instance, in September 2014, over 300,000 people converged on Manhattan for the peaceful People’s Climate March that included mainstream environmental and animal rights activists, a large contingent of interfaith groups, and politicians such as former U.S. vice-president Al Gore, secretary general of the United Nations Ban Ki-Moon, and New York mayor Bill de Blasio.

By the second decade of the twenty-first century, concerns about climate change were not only the purview of environmentalists, just as the rights of sentient creatures were no longer only the concern of animal rights activists. These activists are the radical wing of a broader cultural shift in understanding humans’ place in a multispecies world and a planet in peril. Their actions express trends in contemporary American spiritual expression and moral duties to the nonhuman at the turn of the millennium. Their beliefs and practices reflect a way of being in the world that decenters the human and calls for rethinking our appropriate place in the world vis-à-vis other species. They further our understanding of how younger Americans, in particular, situate the needs of human beings within a world of other species that they see themselves as closely related to and responsible for. I read radical activism as an important expression of social and political trends in the beginning of the twenty-first century that call into question American government and social institutions, as well as fundamental assumptions of what democracy means in the United States in this era and what it might mean in the future.

A READER’S MAP

Chapters 1 and 2 provide introductory material and context for the other chapters. Chapter 1 introduces the reader to activists’ lives and work as well as background on the communities I most often interacted with. Chapter 2 lays out some historical context for the other chapters by charting the convergence of youth culture, North American spiritual and political movements, and environmental and animal rights activism. Radical activism among young adults emerged from the conjunction of a number of historical forces. These forces shaped the particular ways activism has come to be expressed within the radical environmental and animal rights movements of late twentieth- and early twenty-first-century America. In this chapter I suggest that activists travel through networks of affiliation, including the Occupy movement, hardcore punk rock, gender studies classes, veganism, anarchist infoshops (bookstores, rooms, and/or meeting areas where radical literature and other information is shared), and Food Not Bombs. I place these networks within the historical trajectories of social, religious, environmental, and political movements, including anarchism, feminism, gay rights, deep ecology, contemporary Paganism, and youth cultural movements. More than anything else, the radical activist communities I explore in this book are composed of young adults grappling with the realities of the present and imagining a different kind of future in an era of global environmental change. In this chapter I argue for thinking about youth conversion and commitment in ways that avoid demonizing youth. To do so will involve understanding the deep historical roots of young adults’ concerns about the plight of other species as well as their own.

Chapters 3 through 7 cover a lifespan of activism, beginning with childhood experience and ending with mourning the deaths of human and other-than-human beings. Each of these chapters also considers the ways in which particular kinds of emotional experiences shape activist commitments. Chapter 3 focuses on the experience of wonder within the landscape of childhood and introduces the notion that activists’ inner histories composed of memories and childhood experiences are brought to and emerge during activist gatherings and direct actions. The extent to which the remembered childhood landscape is imbued with wonder may affect the intensity of activists’ grief over destroyed landscapes and mistreatment of nonhuman animals. At activist gatherings and direct actions, activists revisit and reconstruct childhood experiences. Rather than severing their lives from childhood, some of them engage in a creative reworking of childhood experiences by creating a deep ecological politics of action.

Chapters 4 and 5 present two possible ways that young people might undergo a rite of passage in the process of becoming activists: one in forest action camps and the other through participation in urban straightedge/hardcore punk rock scenes. Chapter 4 describes the ways in which some activists’ deepening commitments to other species are shaped by love and feelings of kinship in the context of forest activism. In this chapter, I suggest that tree-sits and other actions act simultaneously as rites of passage and rites of protest. Activists travel to forests and experience a sense of belonging in these separate spaces away from a society most of them have rejected. They create action camps and protests as spaces apart, as the larger-than-human world becomes more real to them and the human society they were born into becomes more distant. In these spaces apart they often seek to decolonize and rewild what has been domesticated and colonized. Through complex relationships of intimacy and distance expressed in rites of identification and disidentification, they draw closer to the wild and farther away from other humans outside activist communities. Their vision is one of a feral future in which the wild takes over cities and suburbs, as well as their own bodies and souls, reversing what they see as the relentlessly destructive movement of a doomed civilization.

Chapter 5 explores the interweaving of music, Hindu religious beliefs, and activism motivated by anger in the context of hardcore punk rock. In this chapter, I describe the unlikely convergence of hardcore punk rock, Krishna Consciousness, and animal rights in youth subcultural spaces in order to understand how the aural and spiritual worlds created by some bands shaped the emergence of radical animal rights in the 1990s. At times these music scenes nurtured the idea of other species as sacred beings and sparked outrage at their use and abuse by humans. Bands made fans into activists who brought moral outrage and the intensity of hardcore to direct actions in forests, at animal testing labs and mink farms, and against hunting and factory farming. In this chapter I also explore the extremism sometimes associated with radicalization that can emerge from oppositional stances as activist and hardcore communities negotiate a variety of tensions concerning gender and ethnicity.

In Chapter 6 I explore conflicts within activist communities more intently by considering how activists both soften and sharpen the bounds of inclusion through ritual and spatial strategies, the ways in which they include and exclude self and other as they make and remake sacred and safe spaces within their communities. Chapter 6 analyzes the efforts of activists to create community among people with different agendas and backgrounds and the resultant tensions and conflicts that come about in the process. I look closely at activists’ work to build communities that bring together environmental and animal rights activism with concerns about social justice, especially with regard to people of color. Activist gatherings are imagined as free and open spaces of inclusivity and equality, and yet they set up their own patterns of conformity and expectation. This chapter looks closely at how putting the “Earth first” comes in conflict with “anti-oppression” efforts and vice-versa, as activists work hard, drawing on empathy and compassion, to “decolonize” their communities and “dismantle patriarchy” and transphobia within their movements.

Finally, Chapter 7 describes activists’ grief and despair over loss and extinction. Through the study of grief over lost places, tree friends, whole species, and human comrades, I suggest that protests can be understood as rites of mourning. Memories of childhood wonder, feelings of love and kinship for other species, empathizing with oppressed human communities, raging at injustice with hardcore bands, all make the loss of friends and other species even more keenly felt as activists face the realities of mass extinction and climate change. I explore their experience of environmental devastation and species loss as a kind of perpetual mourning from which they cannot escape. And yet, in all this loss, many of them find hope for a primal future, beyond the human. This chapter looks at how they make losses visible to each other through their own ritualized vulnerability and martyrdom and to the public through ritualized protest and media exposure.

In the book’s Conclusion, I consider the after-lives of activists and activism. What does it mean, after all, to act “for the wild” and “for the animals” throughout one’s lifespan? What comes after youthful conversion, if that life-changing experience is irreversible? What kind of long-term human existence and moral life does radical activism entail? If activism is a kind of liminal existence, an extended rite of passage, what kind of life do activists pass into, and what kind of world do they work to usher in? What commitments and communities take shape and endure? How might radical animal rights and environmental activism be seen in relation to other radical protests of the early twenty-first century, including Black Lives Matter and the Standing Rock Dakota Pipeline protest, as well as antigovernment protests on the Right. I conclude by suggesting what this study has, in the end, to say about youth culture, ritual, memory, and contemporary spirituality in the contexts of radical environmental and animal rights movements and broader political and social shifts in the early twenty-first century. These movements are significant signs of changing times as human and other-than-human communities face and respond to powerful social, political, and climate challenges.