Читать книгу For the Wild - Sarah M. Pike - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

Freedom and Insurrection

around a Fire

To act is to be committed, and to be committed

is to be in danger.

—James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time

My first involvement with a direct action took place in 2012 in western Pennsylvania on the last day of Earth First!’s annual week-long Round River Rendezvous, the largest gathering of radical environmentalists from across North America.1 The gathering was sponsored by Marcellus Shale Earth First!, one of many regional Earth First! groups that alternate in hosting the Rendezvous. Every year, Earth First!ers come together for workshops and opportunities to share local struggles with a nationwide community of activists working on diverse environmental and social justice issues. The annual Rendezvous offers activists a space to express their most deeply held beliefs and debate controversial issues, as well as learn practical skills such as tree climbing and nonviolent resistance. The Rendezvous and other similar gatherings are open to anyone and include newcomers to direct action as well as veteran protesters, and participants in illegal underground actions as well as legal protest marches. The focus of the Pennsylvania gathering was on hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”), which had been responsible for displacing communities and polluting groundwater in western Pennsylvania.2

Earth First! is the most prominent radical environmental organization in the United States today that focuses on direct action. For over three decades, Earth First!ers have regularly engaged in actions “in defense of Mother Earth” and have supported a variety of other related causes, such as animal rights and indigenous land rights. Earth First! has no central structure and is composed of a network of affiliated groups in the United States and around the world, a journal run by an editorial collective, and two annual gatherings: the Round River Rendezvous and the Organizer’s Conference, both planned by different collectives every year. Earth First! was founded by Dave Foreman, Mike Roselle, Howie Wolke, Bart Koehler, and Ron Kezar in 1980. It began as a wilderness protection organization, campaigning to maintain roadless areas under the motto “No Compromise for Mother Earth.” Its founders were inspired by Edward Abbey’s novel The Monkey Wrench Gang (1975), and according to journalist Susan Zakin, they made “ecotage—burning bulldozers, spiking trees, yanking up survey stakes—an attention-grabbing tactic in their no-compromise approach to saving wilderness.”3 Moreover, for Foreman and some of the other founders, direct action was part of “a sacred crusade” to protect the wild from encroachment by humans and their industries.4

In addition to Earth First!, the Animal Liberation Front (ALF) and Earth Liberation Front (ELF) were the most widespread and active radical direct action animal rights and environmental groups in the United States at the turn of the twenty-first century. They are also the groups most often mentioned by law enforcement and news media.5 In the 1990s ALF and ELF became known for their confrontational tactics, acts of animal liberation, and property destruction, especially arson. These networks of activists have no central leadership and few rules. Both ELF and ALF condone property destruction and have guidelines against causing harm to living beings.6

From the 1980s into the twenty-first century, Earth First!ers and other radical environmentalists have advocated a “no compromise” commitment to “the wild.” They have not only practiced monkey-wrenching (sabotaging bulldozers and other heavy equipment, etc.), but have also placed their bodies between trees or nonhuman animals and destructive forces such as logging and fur farming. Environmental actions include a range of activities, such as tree-sits and road blockades to prevent logging and resource extraction. They drop banners in public places, occupy offices of timber or oil companies, and interfere with hunting. The Earth First! Direct Action Manual, available by mail, includes detailed instructions for ground blockades across roadways, aerial blockades such as tripods and tree-sit platforms, hunt sabotage, banner drops, destroying roadways and disabling tires, among a host of other ways to protect the environment and nonhuman animals. More extreme actions may include arson, such as the 1997 arson of the Cavel West horse slaughterhouse by the ELF. Radical animal rights activists such as the ALF also use arson to destroy animal research laboratories or other buildings. They release animals from fur farms and research facilities and set free wild horses that have been corralled. They harass animal researchers, sometimes also destroying their work.7 In order to better understand the ways in which activists arrive at their “No Compromise” stance, and what exactly it means to them, I participated in some of their gatherings and protests.

As the sun was going down on a July evening in 2012, I navigated the back roads of western Pennsylvania, following directions downloaded from the Earth First! Rendezvous website. I missed the last turn and drove several miles before realizing my mistake, as the sky became darker and thick clouds gathered. With relief, I finally drove up to a “Welcome Home” banner and a couple of participants monitoring the gate, who welcomed me and gave me a program with safety warnings about ticks and dehydration, a map of the site, and an “Anti-Oppression and Consent Policy” addressing sexual harassment and other kinds of proscribed behavior. After driving down a gravel road into the forest, I reached a long line of cars parked along the side of the road, apart from the main camp that organizers wanted to keep car-free. Pennsylvania license plates were joined by those from New York, Florida, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Indiana, Oregon, and Ohio, among others, indicating that many activists had traveled from out of state to reach the gathering. Their cars displayed bumper stickers like “I ‘heart’ Mountains,” “Local Food,” “Collective Bargaining,” “I’m Marching to a Different Accordion,” “Eden Was Vegan,” and “Comfort the Disturbed, Disturb the Comfortable.”

As these bumper stickers suggest, the several hundred participants at the Rendezvous had diverse goals and interests. They came to the woods to learn from each other, share strategies, have fun, and participate in a culminating action at the end of the week designed to draw attention to hydro-fracking concerns in the region. Some had dropped out of high school and had been full-time activists for several years, while others were homeless young travelers who spent their time train hopping and hitchhiking around the country. These travelers sometimes participated in tree-sits or other direct actions; they also worked on farms to make money or busked in towns for change. Other participants were on summer break from elite private colleges, state universities, and community colleges. Some activists lived in permaculture communities or worked on organic farms, while others were from squatted houses in New York City. The majority lived in towns and cities, while fewer lived on farms or in rural areas. These activists came from a range of different class backgrounds, including the very poor and the wealthy, but the majority grew up in white middle-class households. I also met activists from working-class backgrounds, such as Thrush, whose family members were factory workers. He too worked in a factory, until one day he quit to join the Buffalo Field Campaign that monitors buffaloes around Yellowstone Park to keep them from getting shot by ranchers when they venture out of the park. Most activists I met were young (18–30) and most were white, with slightly more male-identified than female-identified and a handful of participants who were transgender, gender nonconforming, or people of color. Older participants do show up at these gatherings, but radical activism is overwhelmingly populated by young adults: few activists in the treetops and locked down to blockades are older than thirty.

Gatherings like the Rendezvous are approached as places apart from the world outside and at the same time as homes away from home, hence the “Welcome Home” banner. At gatherings, activists want to feel they can be at home in ways they may not be able to beyond the gathering boundaries. Even as they work and live in it, they tend to believe that industrialized civilizations, and especially American capitalism, are doomed. “I kind of think we’re toast,” climbing trainer Lakes told me.8 For this and other reasons, some activists have separated themselves from the institutions and lifestyles they blame for environmental devastation, choosing to be homeless, living in their cars, or traveling from anarchist squat to action camp. For participants with more conventional lives, the Rendezvous may be a temporary escape from jobs at the heart of a society they feel at odds with. At the Rendezvous and other gatherings I also met nurses, lawyers, teachers, counselors, farmers, and small business owners.

That summer of 2012, deep in the Allegheny forest, I set up my tent on my first night just as the rain began to fall. Because of the weather, I stayed inside until dawn. The free communal breakfast, prepared by a collective called Seeds of Peace, was my first chance to join the larger community. The Seeds of Peace kitchen offered three meals a day, which allowed everyone an opportunity not only to eat but also to network and share what they had learned in the workshops, or where they had found an edible plant or swimming hole. Free meals and a volunteer-run kitchen are important features for those who travel alone to gatherings or are new to the movement, since eating together is an easy way to make friends and feel part of the community. Much of the food for the kitchen is donated or dumpstered (dumpstering is the practice of rescuing edible but overstocked or out-of-date food found in dumpsters behind grocery stores). Like everything else at these gatherings, food preparation, cooking, and dishwashing are done by participants who volunteer each day, even though a handful of people are in charge of the kitchen and responsible for bringing stoves, pans, and other supplies to the gathering site. Communal meals are healthy, varied, and include vegan options, as well as the occasional meat dish if someone donates a dumpster find of hot dogs.

Animal rights activists have national gatherings too, but the ones I attended were more like conventions than the Earth First! Rendezvous, charging a fee for attendance and featuring a room of vegan products for sale. They draw from a spectrum of the animal rights movement, including business owners, mainstream activists involved with letter writing and lobbying, and radical activists taking part in illegal activities. The largest gathering I participated in, the Animal Rights National Conference, took place in hotel convention rooms and was held alternately in Los Angeles or Washington, DC. Property destruction tactics used by the ALF and other radical animal rights activists were more controversial in this context than at the Earth First! Rendezvous.9

At radical environmentalist gatherings, animal rights campaigns were discussed and a number of activists participated in both movements, especially in organizations that defend wild animals, such as the Buffalo Field Campaign. The Earth First! Journal covers animal releases and other ALF actions in its pages, and animal rights campaigns are familiar to many radical environmentalists, especially because some of them have been involved with both movements.10 In theory, participants at the Rendezvous supported animal rights, but tended not to be as focused on factory farming, and thus on dietary practices, as animal rights activists. Opposition to factory farming is a cornerstone of animal rights, along with other issues such as vivisection (experimenting on animals for medical research or product testing), killing animals for fur, and keeping wild animals in captivity at zoos and animal parks.

While many activists are omnivores, just as many are vegetarian or vegan, for both moral and environmental reasons. As Paul Watson, founder of Sea Shepherd and a long-time campaigner for marine animal rights, put it, “A vegan driving a Hummer contributes less to global greenhouse emissions than a meat-eater riding a bicycle.”11 In addition to Watson’s environmental argument, activists are also motivated to become vegans or vegetarians as a result of personal experiences with nonhuman animals or horror over the conditions of factory farming.

After breakfast each day of the Pennsylvania Earth First! Rendezvous, someone blew a horn and participants hanging out in the dining area yelled, “Morning Circle!” As the daily community forum and gathering of the entire camp, Morning Circle served to help organizers find volunteers to handle security, work with medics or as conflict mediators, dig latrines, or help in the kitchen. It also allowed for the airing of more general community concerns, often about safety issues or exclusionary practices and oppressive attitudes among Rendezvous participants. Workshops were held in designated areas throughout the camp that had been given names like Indiana Bat, Bog Turtle, Wood Rat, and Allegheny. Because Earth First! aims to be a leaderless movement, anyone can propose a workshop at these gatherings. There is no selection committee: other participants either show up for a workshop or they do not. Workshops on skills involving safety such as climbing training or medic training are, however, conducted by people who are recognized as having the appropriate skills and experience.

Workshops at Earth First! Rendezvous I attended included the following topics, which I list at length because of what they reveal about the diversity of activist interests in both ecological and social justice issues:

•Action Legal Training

•Practicing Good Security Culture

•Environmental Racism and Solidarity

•Media for Actions

•Unconventional Hydrocarbons

•Know Your Rights

•Men Challenging Sexism

•Propaganda for Revolutionaries

•Cob Building

•Direct Aid on the Border

•Uniting Anti-Extraction Movements

•Cultural Appropriation

•Edible Plants for Wellness

•Mountaintop Removal

•Misogyny in the Catholic Church

•Radical Mycology

•Basic and Advanced Climbing

•Silk-Screening

•Dismantling Patriarchy

•Non-Violent Communication

•History and Future of Animal Liberation

•Red Wolf Re-introduction

•Restoring the American Chestnut

•Women and Trans Self-Defense

•Radical Mental Heath

•Banners and Art

•Plant Walk

•Intersectionality of Oppressions

•Warrior Poets Workshop

•Police Liaison Training

These workshops indicate the many concerns of activists at the Rendezvous and their desire to link environmental campaigns to social and political issues. They also reveal the ways in which activists prepare for protest actions at the same time that they create the kinds of communities they want to live in.

Although many participants at the gatherings I attended had been active in forest campaigns and antiextraction protests, they were also involved in other kinds of activism. Activists’ interests bridge social justice and environmentalism and include working in solidarity with Native American communities, providing food and water to illegal immigrants crossing the southern border, and organizing coal mining communities in West Virginia. At the Rendezvous in Pennsylvania, workshops to educate attendees on fracking issues included identification of risks to human health as well as to the environment. The Rendezvous also featured workshops on the following topics: “indigenous solidarity” through Black Mesa Indigenous Support; mountaintop removal campaigns in West Virginia; and No More Deaths, a coalition of religious groups and other concerned activists who make water drops in the desert along the Arizona border.12 These workshop topics suggest that stereotypes of “tree-huggers” and profiles of the “eco-terrorist next door” miss the extent to which radical activists are involved in a wide range of activities that challenge governmental policies and corporate practices that have an impact on humans as well as the larger-than-human world.

Raising serious social and personal concerns at gatherings often results in fraught discussions and long, frustrating workshops. Trainings for dealing with police during actions stir up difficult emotions; sessions of letter writing to prisoners serving long prison sentences, planning for jail support, and poems written in memory of activists who have died at protests remind everyone of the risks involved in what they are doing. Nevertheless, the atmosphere at gatherings and many actions is also one of serious play.13 At the 2012 Rendezvous, a puppet show on “security culture” used humor to instruct the audience on what not to talk about with their friends in order to protect themselves and others from arrest and prosecution. Talent shows at gatherings showcase a variety of performers, from slam poets knocking capitalism to banjo players singing old coal mining songs. Humor is especially important in the atmosphere of repression that has haunted activist communities since stiff sentences were handed down to some of their comrades during the “Green Scare,” a roundup of activists by U.S. government agencies.14 A sense of humor also infuses the actions themselves. While one or two activists are in precarious positions on blockades, nearby a group of “radical cheerleaders” may be cheerily performing dances and songs to a drummer corps passionately beating on five-gallon plastic buckets. Serious play entertains participants and conveys activists’ message with a lighter hand.

One road blockade by Earth First!ers in 1996 to protest logging of ancient forests in Washington State’s Olympic Peninsula involved a mock living room in the middle of a logging road. Here, as often, humor and performance art worked together in the context of an action that activists also took seriously as part of their struggle to prevent ancient trees from being logged. They called the blockade “The American Family.” It consisted of activists locked to an immovable living room composed of couch, chairs, and a table filled with cement and facing a television. In this action, “Uprooting the familiarity of the domestic sphere into the unpredictable vastness of the old-growth forest directly confronted the conceptual separation of nature from culture,” according to one observer. Locked to their seats, activists faced off against logging trucks and forest service personnel in a setting reminiscent of performance art.15

Activists approach protests with a mixture of excitement, humor, fear, pride, anxiety, and contestation. Not everyone agrees on tactics, and many elements of actions can be unpredictable, especially with over a hundred people involved. It is uncertain if anyone will be arrested or injured and whether the news media will show up to publicize the action. Not everyone at the Rendezvous stays for the action. Some have records for previous actions and cannot risk arrest; others have young children at home or have come to the gathering to learn and share information but do not want to be involved in direct action, even if they support those who do.

Preparations for the 2012 action in Western Pennsylvania took place throughout the week of the Rendezvous, though details of what we would be doing and where we would be going remained vague. Participants divided into affinity groups and decided what level of risk they wanted to take during the action: green, orange, or red, with red carrying the highest risk of arrest and green the least. Some of us volunteered to serve as legal and jail support, or media and police liaisons. Medics paired up with other medics to work in teams. Other participants made banners, posters, and bucket drums or practiced chants.

On the morning of the action, we set out before dawn. It was a lovely but nerve-wracking drive through the rural hollows and thick forest as we tried not to lose the taillights of the car in front of us on the dark and mist-covered road. Through the mist, in a long caravan of cars, the five activists I was riding with talked quietly. We finally arrived at our destination and parked along a rural road near the entrance to a fracking site in the Moshannon State Forest. As a member of the “green group,” I was stationed at the entrance to the forest, in front of the first blockade, but far away from the main action site. We sat in chairs in the middle of the entrance road with a banner reading, “Our Public Land is not for Private Profit.” Other banners at the protest were “We All Live Downwind” and “Marcellus Earth First!, No Fracking, No Compromise.”16 We got out our bucket drums and held up signs while one of our members played guitar. A young woman from New York City sprinkled some “holy water” around the protest site that had been “blessed by a medicine man” and given to her by a friend who could not participate in the action. “It can’t hurt,” she told us. Like many activists, she was practicing a spiritual eclecticism that borrows from and melds together bits and pieces of various religious traditions and worldviews, in this case Catholicism (“holy water”) and indigenous traditions (“medicine man”).17

The center of the action, which we could neither see nor hear, was up the road from where we were stationed. Earlier in the morning, a couple dozen activists had hiked through the woods and constructed barricades of fallen trees and branches across the road. Two activists in the “red group” climbed about sixty feet into some trees and drew their support lines across the road. One of them was in a hammock rigged so that if anyone tried to get through the lines, the hammock would fall. Meanwhile, some “scouts” went ahead to see what was happening at the drill rig farther up the road. The seventy-foot-tall rig was operated by EQT Corporation, one of the largest drillers in Pennsylvania, with about 300 active wells in the western part of the state across what is called the Marcellus Shale.18 Activists approached the workers who were already at the site to let them know that the action was intended to be nonviolent. Before long, Pennsylvania state police arrived and walked around with assault rifles. “You are supposedly adults,” one of the officers told activists, “and you’re acting like children.” As law enforcement personnel became increasingly frustrated and tensions seemed to be escalating, an activist locked his head to one of the anchor lines with a bicycle u-lock to help protect those in the trees.

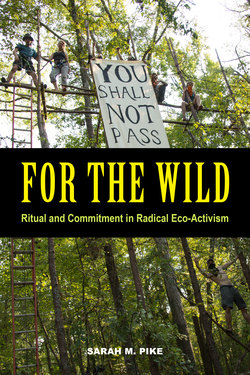

Fracking site road blockade. Photo: Marcellus Shale Earth First! Used with permission.

Back down by the entrance, members of the green group, including myself, were trying to draw attention from locals driving by on the county road. We spent hours chanting and banging on drums every time a car passed us. Most of the cars slowed to look at us since there was probably not much else happening on a Sunday morning in rural Pennsylvania. In the afternoon, some local farmers showed up with a big basket of blueberries. They sat down with us on the side of the road and described how a nearby fracking operation had polluted groundwater on their organic farm. Local politicians had ignored or dismissed the seriousness of their concerns, so they were hoping our presence might help raise awareness about the issue.

Periodically, someone would come down the forest road to update us on what was happening at the barricade as the situation there continued to escalate. Marsh, who had his head in the u-lock, told me later, “there was a lot of drama, everyone yelling, because the police weren’t being careful.”19 By early evening the police decided to act. In a video made of the action, a cherry-picker (a bulldozer-like machine with a lift) and a group of police officers started to approach the blockade where the two activists were perched. As the cherry picker followed behind them, officers approached the support lines while frantic activists yelled at them to back off: “Don’t touch the line!” We’re nonviolent,” shouted one activist, “and what you’re doing is violent.” “Please listen to my friends,” called the activist from the hammock, “my life is at extreme risk right now. Please think twice before you cut that line. I’m begging you.” The bucket of the cherry picker hit the support line, but eventually they brought the activists safely down to the ground and arrested them. Three arrests were made at the action, but in less than an hour, all three activists were released without serious charges.20

After a long day in the forest, I drove away from the 2012 action, joining other participants leaving camp. Some activists went back to clean up the campsite, while others journeyed to other actions near and far or hitched rides to the homes of new friends. Still others drove home to their families or work lives. Many participants returned to campaigns in their local regions, from antifracking in Maine to antilogging in Oregon. Two participants in the 2012 Rendezvous told me they were heading back to their hometown, inspired to start an Earth First! group in their bioregion.

The 2012 Rendezvous action was the first shutdown of an active fracking site in the United States, although the site was up and running again the following day. In the several years following the Rendezvous action, Marcellus Earth First! and other antifracking activists held rallies and educational meetings about fracking and the Marcellus Shale.21 In March 2014, they organized a road blockade during which protesters in the middle of a forest access road locked themselves to a tube full of sixty pounds of cement. Shalefield Justice Spring Break, modeled on a similar program in West Virginia to fight coal mining, brought college students to the area for activist training and to support the blockade. During the blockade they organized a simultaneous rally at Anadarko Petroleum’s corporate offices.22 In January 2015, Pennsylvania governor Tom Wolf announced he would sign an Executive Order “restoring a moratorium on new drilling leases involving public lands . . . ending a short-lived effort by his predecessor to expand the extraction of natural gas from rock buried deep below Pennsylvania’s state parks and forests.”23

Direct actions are defined as successful or unsuccessful in various ways. In this case, widespread concerns about fracking facilitated by activists’ public actions and educational efforts seemed to make a difference. In tree-sits to prevent logging or pipeline construction, sometimes areas are protected (as was the case when a timber sale in Warner Creek/Cornpatch Roadless Area in Oregon was dropped after an eleven-month blockade that began in 1995). Other times they are long running in nature, such as the 2012 Tar Sands Blockade tree village in Texas, which eventually failed to achieve activists’ immediate goals (construction continued by going around the tree village).24 Yet even the Tar Sands Blockade was effective on some level. Publicity helped bring attention to links between oil spills and pollution, between fossil fuels and climate change, and activists forged coalitions with local landowners and churches, suggesting possibilities for a broad-based movement against extraction industries.25 The Earth First! 2012 action in Pennsylvania, which was covered by national news sources, also served to draw attention to fracking, making visible what might otherwise be hidden deep in forests or rural areas away from critical eyes.26