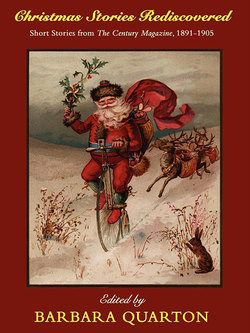

Читать книгу Christmas Stories Rediscovered - Sarah Orne Jewett - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеA CHRISTMAS DILEMMA: (A TRUE STORY), by Anonymous

The dilemma in this story is probably familiar to most readers. During the Gilded Age, Christmas gift-giving expanded to include not just family—as had been the custom—but also friends, acquaintances, and business associates. For the first time in American history, people felt obliged to weigh the value of their relationships and give gifts accordingly. A Christmas Dilemma is a lighthearted look at a sometimes vexing social predicament.

“John,” said Mrs. Spencer to her husband, “I don’t know what to do about the Martins’ Christmas presents.”

Dr. Spencer looked up from the paper he was reading. “Do?” he said vacantly. “What do you mean?”

Mrs. Spencer laid her work in her lap and moved the student-lamp on the table between them, to get a better view of her husband’s face.

“Come up to the surface, John,” she said, “and listen, because I really need your advice.”

The doctor rested his paper on his knees and “climbed over his glasses” at his wife.

“Go ahead,” he said; “you have my attention.”

Mrs. Spencer continued seriously:

“You know what a nuisance these Christmas presents have come to be between the Martins and ourselves, and how much I want to stop them; and yet—” She paused, and her husband’s face assumed an amused expression.

“Well, my dear Ellen, my advice is, leave off sending them. It is the solution of the difficulty. It will immediately relieve the situation.”

Mrs. Spencer nodded, and tapped the table with her thimble.

“It is what I wish to do,” she said. “I am sure it is as great a worry to Mrs. Martin as it is to me; but the point is, how to leave them off. I cannot be the first to stop. Just suppose I should send nothing, and she should send the usual great basket with a present for every one of us—you, the children, the servants,—last Christmas she even sent a collar for Don,—I should die of mortification.”

Dr. Spencer took off his glasses and looked gravely across the table at his wife.

“I have often thought,” he said, “that there were too many women’s societies in this town; but I see the need for one more—a Society for the Suppression of Christmas Presents. Send out circulars, beginning with Mrs. Martin. You ought to get a large and enthusiastic membership.”

Mrs. Spencer sighed, and took up her work again.

“You don’t advise me at all,” she said; “you only joke, and I really think this is a serious matter.”

“My dear Ellen, I am willing to advise you, but the whole difficulty seems to me a ridiculous one. There is only one thing to do. Stop short now. Suppose she does send you a basket? It will be the last time. It’s the shortest and simplest way to end it.”

“I might,” said Mrs. Spencer, meditatively, “not send anything at Christmas, and then, in case she does, I could return them presents at intervals throughout the year—on their birthdays, at Easter, and so forth.”

“Good Lord, Ellen,” hastily interrupted her husband, “don’t do that! You’ll have her returning the birthday and Easter presents. It would be worse than ever.”

“Yes; I am afraid that would not do, after all,” said Mrs. Spencer, looking more troubled than before.

Dr. Spencer reached out for the poker and tapped open a lump of soft coal on top of the fire. A blue flame shot up through it, and a little spiral of smoke licked out into the room.

“Ellen,” he said, emphasizing his words with taps of the poker on the grate, “take my advice: cut it short, and just bear it if you do have to take presents from her this year. Carroll Martin is a man I shall never respect again after his course during the last election, and anything is better than carrying on this perfunctory friendship. We no longer see enough of any of them to justify our exchanging presents, and I am sure Mrs. Martin will thank you as much as I shall if you will take the bull by the horns now and be done with it.”

He looked at his wife, but she did not answer. Her eyes were bent upon her sewing, and her expression was unconvinced.

Dr. Spencer set down the poker, took up his paper, and settled himself back in his chair again. He was not one of those who go on and split the board after they have driven home the nail.

“You have my opinion,” he said, and went on reading.

The Spencers and Martins had been, some years before, next-door neighbors. The Martins were then newly married and strangers to the place, and the first Christmas after their arrival, Mrs. Spencer, in the kindness of her heart, had sent over a bunch of flowers, with a friendly greeting, to her young neighbor. Her messenger had returned with Mrs. Martin’s warm thanks, and a pretty sofa-pillow, hastily snatched up and sent to express the little bride’s pleasure and gratitude.

Such a handsome gift, in place of the “thank you” expected, had decidedly taken Mrs. Spencer aback, and when the next Christmas came, she took care to provide a pretty pin-cushion for Mrs. Martin and a dainty cap for the baby who had by that time been added to the family. This occasion found Mrs. Martin also prepared, and she promptly responded with a centerpiece for Mrs. Spencer, an ash-tray for the doctor, and a doll for their little Margaret.

From this time on each year the burden grew. Several children had been added to both families; each one was separately remembered, and, in the old Southern Christmas fashion, presents for the family servants had been added to the list, one at a time, until not only nurse, coachman, and cook had been included, but, as Mrs. Spencer said, the previous Christmas had even brought her a collar for the dog.

During these years both families had moved. Both had built new homes, on the same street, it is true, but a block apart, so that they were no longer near neighbors, and lately the two men had been on opposite sides of a bitter political contest. “Warmth had induced coolness, words had produced silence,” and the relations of the two families had become only formal.

The Christmas presents had been kept up only because neither woman knew how to stop, and as Mr. Martin had in the meantime made money, and become, according to Southern standards, a rich man, Mrs. Spencer felt more than ever determined “not to be beholden to them.”

On the evening in question she said no more, but the night brought counsel, and next morning she informed her husband that she had decided what to do. She would buy the presents as usual, but she would wait, before sending them on Christmas morning, to see whether Mrs. Martin sent to her. “And if I do not need them, I can put them up for the children next Christmas,” she concluded triumphantly.

Dr. Spencer did not approve of this ingenious plan, but his wife persisted. “Not for worlds” would she have a great lot of presents come over from the Martins’ and have nothing to send in return.

Christmas morning came, and, while dressing, Mrs. Spencer told her husband that she should send little Jack out on the front sidewalk with his fire-crackers, so that he could keep a lookout down the street and report any basket coming from the Martins’.

Hers was packed and ready. Every bundle was neatly tied up in white paper with ribbons and labeled: “Mrs. Martin, with Christmas greetings”; “For Little Charley, with Mrs. Spencer’s love”; “Mammy Sue, from the Spencer children”; and so on. And Mrs. Spencer reflected with satisfaction, as she deposited a new harness for the Martins’ pug on top of the pile, that nobody was going to get ahead of her.

Breakfast over, and Remus, the doctor’s “boy,” instructed to keep himself brushed and neat, ready at an instant’s notice to seize “the Martin basket,” as the doctor called it, and bear it forth, Mrs. Spencer’s mind was at rest. Jack was on the sidewalk, banging away, but keeping a sharp eye out toward the Martins’, too; for he had scarcely been there five minutes before he called to her that Robbie Martin was playing on his sidewalk and watching their house like anything.

A short time passed, and Jack came running in. “Mother, I see Mammy Sue coming this way with a tray,” he said.

The doctor called from his study: “How do you know she is coming here?” But Mrs. Spencer had not waited to hear him; she was already at the back door calling excitedly, “Remus, take the basket!”

“John,” she cried, running back, “you see the Martins are sending us presents,” and she got to the window in time to see Remus issuing forth with his burden. As he reached the street and turned toward the Martins’, into the house rushed Robbie, calling, “Mother! Mother!” and a moment later out popped the Martins’ butler, Tom, with a large basket brimming over with tissue-paper and blue ribbons on his head, and took his way toward the Spencers’ at a brisk trot. It was quite a race between him and Remus; they grinned cheerfully as they passed each other half-way. Mammy Sue went by the gate with her tray, but Tom came in and set his load down in the hall, where Mrs. Spencer received it with a smile as fine as a wire.

A few minutes later the doctor came out of his study. His wife, her lips pressed together and her eyes very bright, was kneeling beside the basket, handing out be-ribboned packages to the children, who were exclaiming about her. He stood looking on in silence until she handed him one marked, “For Dr. Spencer, with Mrs. Martin’s kindest wishes,” which he opened.

“Beautiful!” he said. “Just what I have always needed. My office wanted only a pink china Cupid, with a gilt basket on his back, to be complete.”

Mrs. Spencer made no reply, nor did she look up; her hands fluttered among the parcels. The doctor considered the top of her head for a moment.

“Ellen,” he said gently, “there was just one little mistake in our calculations: we never thought of Mrs. Martin’s being as clever as we are, did we?”

Mrs. Spencer looked up and laughed, but her face quivered.

“John,” she said, “I’ll always love you for that ‘we’.”