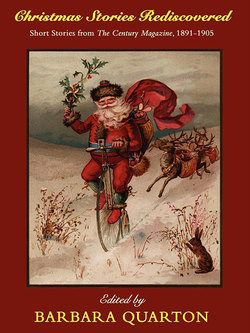

Читать книгу Christmas Stories Rediscovered - Sarah Orne Jewett - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеHOW “SANDY CLAWS” TREATED POP BAKER, by Elizabeth Cherry Waltz (1866-1903)

In 1863, Thomas Nast illustrated Clement C. Moore’s “A Visit from St Nicholas,” and Santa Claus became widely accepted as the character of the modern Christmas. The main character in this story, Pop Baker, was too old to have heard about Santa Claus in his youth. This story describes Pop’s first experience of Christmas with Santa Claus.

It is certain that Pop Baker never heard of Santa Claus in the days of his early youth. He was over seventy years old, although no one would ever have guessed it. When he was a yellow-haired urchin he was as far away from civilization as are the inhabitants of Central Africa nowadays. Louisville was a prosperous community in the early thirties of the nineteenth century,—one where the brother of the poet Keats and other scholars found polished and congenial society,—and it was only twelve miles away; but the way to it from the highlands far south of the city was over swampy morasses and through vast stretches of the “Wet Woods,” forests so dense that even the Indians turned aside from them. There grew numerous ash-trees and the larger forest monarchs, and all were so thickly set together that the white man did not force his way through them for a century. Beyond then lay the hills, huge shoulders and boulders; and here Pop Baker was born, and here he lived in 1902.

Over seventy years old was he, very tall and very straight and broad-shouldered, and slightly silvered of hair and chin-beard. Also he was rosy-faced and merry-eyed. Fate had found him a hard nut to crack, and left him at the end of the span of man’s life unscathed and wholesome. He had been married twice at least. He had several children, of whom “Doc” and “Jimpsey” remained on this mundane sphere, shiftless hill-billies, with none of the old man’s grit or philosophy. Another, a daughter, Mahale by name, had achieved notoriety by the accumulation of nine children in a dozen years. She departed this life “’thout doin’ no more dammidge,” Pop said, “than ter leave seven livin’.” The “seven livin‘” proved for half a dozen years the old man’s burden. He mothered them, and he allowed the father, Pete Mason, to live under his own roof. But when “leetle Pop” was six yeas old, his grandsire decided on a course of action, and was prompt indeed about it. He caught Pete at the rail fence one morning when the latter was mounting a mule to ride off to Pausch’s Corners for an early bracer-up.

“Petey, I hear ye air goin’ reg’lar-like up ter Kuykendall’s. Thet air all right, but ye mought ez well be narratin’, over yan, thet ye’ve the seven livin’ ter pervide fer yit. I’m a-gittin’ ter thet time o’ life when I wanter hev a leetle freedom ’n’ enj’yment. Ye mought ez well let on ter whichever one of them gels ye‘re shinin’ up ter thet, ef she air bent on marryin’, she must tek the hull bunch ‘long wid ye.”

Peter narrowed his eyes.

“Ye mought mek a sheer-up,” he debated; “thar’s a hull lot o’ ’em.”

Pop Baker shook his head decidedly.

“I’m too old ter be raisin’ famblies,” he said, “an’ ye’ll hev ter rustle a leetle more yerself from this hyah time on, Petey. They air all on their feetses now, an’ rale fat an’ sassy. Ef one of them Kuykendall gels hain’t willin’, consort elsewhar. I calkilate ter give ye a mule, a bar’l o’ sorghum, an’ three feather beds fer the childern. Ye must do fer yerself with yer settin’ out from wharever ye marry any one.”

As Peter Mason was still a strapping, swaggering fellow, he had little difficulty in persuading Georgella Kuykendall to assume the position of stepmother to the “seven livin’” and wife to himself. The family removed themselves in the springtime clear over Mitchell’s Hill, and, under Georgella’s thrifty and energetic reign, got on fairly well.

For the first time in his life Pop Baker enjoyed the sweets of entire freedom. He fought off Jimpsey’s vehement offers to “keep house” and Doc’s inclination to make his home a half-way tavern between his own cabin and Pausch’s Corners. He had thirty acres to farm, two mules, and a cow. His house was part stone and part log, with a noble chimney of rough stone. He had wood and water and a garden.

All summer he reveled. He worked when he chose, he hitched up and rode around In a buckboard behind his best mule, whose name was Bully Boy. All his meat came from the woods—birds, rabbits, squirrels, racoons, and even a fat opossum now and then.

“Look at thet muscle, wull ye?” he would say to the young men pitching quoits at the picnics. “Thet thar muscle hev been made tough on work an’ wild meat. Tame meat never made a man like I be.”

He had his own ideas of sport.

“D’ ye s’pose I’d ever kill fer the pleasure o’ hearin’ a noise an’ seein’ a creatur’ die?” he said. “I live like the birds an’ the varmints. I kill ter eat—the Almighty’s way.”

In front of him, across the rough road and over a half-cleared and enchanting woodland of old trees, rose the wildest of hills to the west; and behind him, half a mile to the east and south, were other cones and shoulders, strangely formed and freakishly upheaved, with narrow hollows between them and meandering streams tearing down, and falling down, and laughing over jagged rocks. Over the rarely trodden forests and on these hills tramped Pop Baker at will. He gave his whole soul to the delight of solitude, of falling in with nature’s moods. His heart grew more tender as the days went by. He gathered a great hoard of nuts for the children. He halved the crop from his patch of pop-corn, and he traded corn for a barrel of red apples. Something was working in him that, in earlier years, had never bothered him. The “seven livin’” had brought in Christmas and “Sandy Claws” to the cabin with them, and the idea would not be swept out with their going.

All along through the fall Pop Baker was the maddest of merrymakers at the dances, the weddings, infares, and quiltings. He never heard of any social event, far or near, but he greased up his boots, tied his red comforter round his neck, and racked Bully Boy over the hills to it. He never waited for an invitation, and he was always expected. There was sure to be some congenial spirit there, either a young widow or a mischievous girl willing to spite a bashful swain, or, at the worst, one or two uproarious young blades to slap him on the shoulder.

Nothing daunted him, nothing stayed him. The cold only made his cheeks rosier; his eyes sparkled. They called him “Old Christmas hisself”; they applauded him, and egged him on to dance and flip speech. So the days and nights passed, and Christmas was at hand.

Bully Boy and The Other—for Pop Baker disdained, in his partiality, to name his less intelligent mule—pulled up over Jefferson Hill and down into Bullitt County with Pop’s Christmas for Mahale’s young ones in the wagon. There were the apples and the nuts, the molasses, and a big green ham. Mrs. Peter gave him a welcome, a good meal, and started him home early. To her he was only an old man who ought to be in his chimney-corner at night. The seven swarmed lovingly over him as he mounted the seat. “Leetle Pop” smeared him with molasses as he murmured:

“Wanter buss ye one, gran’dad. Ye’re so dern goody, ye air!”

Then came a splendid ride homeward under the frosty starlight. Pop Baker sat on an old skin robe and rode with a bed-comfort and a horse-blanket around his legs. Straw heaped the wagon-bed in front of the empty barrel. The wagon wheels creaked over the road, broke into the forming ice on Knob Creek, and rattled down the steep slope of Mitchell’s Hill. Then along the deep shadowy ways he passed through interminable woods, where sometimes there were hollows hundreds of feet below him, and sometimes there was a narrow cut under a rocky cliff where dry branches broke and crackled down. Sometimes there appeared below him, like fireflies or sparkling human eyes, half-frozen streams that ran and crossed, and reflected back the stars. Bully Boy had his master’s own spirit, and literally dragged The Other up and down hill right sturdily. Pop Baker did not have to drive, Bully Boy would have resented any imputation of being driven. He knew every step of the way, and he pulled—that was his duty, Christmas or Fourth of July—without shirking. Pop took it easy, and watched the processional of the stars across the cathedral of the heavens. Now he was on the highest point of the county, on Jefferson Hill. Far, far away in the wide valley he saw glows of light. He knew that there lay the distant city, with its hundreds of shop-windows lighted up and Christmas-gay, draped with tinsels and bright colors, and full of what in his sterner moments he called “trash,” in his softer moods “purties.” The thick carpet of fallen leaves on the road deadened the sound of the wheels and the mules’ feet. Pop Baker looked at the stars with a new awe and joy.

“Might’ fine, them! Sorter hail a man ter notice. Seen ’em walkin’ over thet big space many a night, but, dern it all! they never war so bright. Might’ good comp’ny—the bestes’ o’ comp’ny fer an ol’ man. Merry ’n’ cheerful, ’n’ deliverin’ the message thet thar hain’t no doin’ erway with whutever air made ’n’ placed—anywhar. Thet’s whut I hev figgered out. I been put right here, ’n’ I hev figgered out I’m in the percesslon, an’ bount’ ter stay,—out o’ sight er in sight—perceedin’ on an’ never stoppin’, ’ca’se I oncet war made an’ do be.”

No human being had ever seen the rapt face Pop Baker turned to the stars—no one but his Maker.

“Folkses thinks ez how I’d git lonesone; but when a man gits ter some age, he air got suthin’ er nothin’ in ’im—Dern yer buttons, Bully Boy! whut air ye stoppin’ fer?”

There was a halloo, clear and high, from the bottom of the hill.

“An’ ye heared that when I didn’t, Boy? Waal, consarn ye! what else hev I got sech a smart mule fer? Halloo, yerself, down thar!”

“Come on down came up a stentorian sound. Then a bound barked long and loud.

“Tobey shore we wull, Bully Boy,” commented Pop Baker; “for I’ll bet ye yer feed it’s some un thet hev been ter town an’ got plumb full o’ Sandy Claws, wagon-bed an’ all. We air comin’ down!” he hallooed merrily; then he began singing one of his own improvised songs on cider—the one that was always the chief delight of the hill folk’s revels and routs:

“Ol’ Unkie Doc an’ the cider-pot!

He liked um col’ an’ he liked um hot;

Stick in the poker, an’ make um sizz,

Hi! d’ ye know how good thet is?

“Tetty-ti, tooty-too!

You likes me, an’ I likes you;

Stick in the poker, an’ make um sizz,

Hi! d’ ye know how good thet is?”

He had rollicking company in the chorus long before he got to the bottom of the hill. If you had seen that hill you would have said that Bully Boy tumbled down it. As for The Other, it was his place in the order of things to fall after.

“Hi! d’ye know how good thet is?”

And there the two wagons stood side by side at a slightly widened curve in the steep road.

“Now, would ye think it!” said a sarcastic voice. Ef it hain’t Pop Baker, an’ not some young rake a-trapesin’ after a sweetheart on a Christmas eve. But I orter ’a’ knowed thet mule. Not another un in the county ‘d run down Jefferson thet erway.”

“He air gittin’ thar, Dink Smith,” retorted Pop Baker; “’sides, Bully Boy air allers cavortin’ arter nightfall, goin’ or comin’. The Other has plumb los’ his wind, I swanny! Waal, how’s Christmas?”

“Burnin’ me up,” replied Dink facetiously. “I sold a hawg, an’ some sorghum, an’ some eggs, an’ some butter, an’ dried peaches. Got groceries in thet box, closes in thar, ’n’ small tricks fer the kids in thet thar chip basket. Stop yer howlin’, ye Dan’el Webster!”

The hound in the wagon whined and subsided.

“Wonder yet ol’ woman hain’t erlong with ye,” observed Pop Baker.

“I guess ye hain’t heared thet we got a boy yistidday,” returned the young hill man. “Yes, by the great horn spoon, we got ’im, Pop! An’ looky here whut I bought fer ’im—now! Jes ye wait—I’ll strike a match. Ye shorely must see them that purties—jes must.”

By the light of several matches a small pair of red-top boots were exhibited, handled, and commented upon. Pop Baker’s face was a study.

“Waal, waal!” he said, much impressed, “thar’s a thing ter grow up ter fit! Um-m-m! Dink, I’d ’a’ got ye ter hev fotched me a pair o’ them ef ever I’d ’a’ known sech things war. War did ye git ’em?”

“Seen um in a winder,” said Dink, solemnly. “Hones’ Injun, Pop, I war so ’feard they’d be sold afore I got back a-sellin’ my hawg. I jes went In regardless, an’ ast thet storekeep’ ter wrop ’em up ’n’ let Dan’el Webster hyah guard ’em. He gimme jes half an hour. Dawg my buttons ef the houn’ would let a pusson in the store! But I got them small boots, Pop! Ain’t them beaut’s, heh?”

“Them shorely air,” asserted Pop Baker, solemnly. “Ye air too lucky fer it ter last, Dink—a boy, ’n’ strikin’ them boots. Waal, I wisht ye merry Christmas! It air gittin’ cold, haint it?”

“Whut ye expectin’ yerself?” quoth Dink, whose heart had opened under Pop’s generous praise. “Ye orter hev suthin’ fine yerself, shorely.”

Pop tried to pass it off airily.

“I dunno whut Sandy Claws’ll do for me,” he said slowly. “I did mention ter Jimpsey thet I’d feel peart ter middlin’ ef the ol’ chap’d drap me a real visible houn’ pup down the chimbly. Thet larst houn’ I hed outen Ase Blivin’s breed war thet triflin’ an’ cross thet the neighbers pizened him. He clumb right up inter passin’ wagons. I wanter own a pup thet hev got some nateral ondertandin’, an’ ef he bites when he’s growed up, he wull bite with reason.”

“Dawgs air truly gittin’ might’ triflin’ these days,” commented Dink, leaning back. “But, Pop, I’m goin’ ter give ye suthin’ I got right off a rale peart Sandy Claws pack up in town, An’ don’t ye open it tell ye git it home, an’ ye gits yer fire a-goin’ good, an’ air settin’ roun’ thar. Then ye puts yer box on a cheer ’n’ ye turns on the leetle wire. Dern it all, but I wisht I war thar when ye does it! Ye’re sech a sport yerself thet I hates ter miss it.”

“Haint I robbin’ o’ ye?” asked Pop Baker, politely, although he was leaning far over and reaching out his hand in the wildest curiosity.

“Naw, naw; the feller threw thet thar trick in—an’ I got some other stuff. I’ll jes keep a-bustin’ ter-morrer ter think o’ ye an’ thet box. Waal, here’s ter yer Christmas in the mornin’, Pop! So long, ye!”

Pop Baker clasped the small, hard parcel ecstatically to his breast while mechanically holding the reins. Bully Boy seemed to realize the importance of haste as he fairly bounded on, dragging The Other without any mercy. They rattled over the stony creek road, and finally reached the low house. In twenty minutes Pop Baker had given the mules a big feed in the barn, and was stirring up his carefully covered wood fire on the hearth with a pine stick. It struck him that the room was very nice and warm.

The pine stick flared up high, and Pop Baker looked up at the high, rough mantel-board for the one small tin lamp that he possessed. A new glare struck his eye. On the shelf sat a shining glass lamp with a clean chimney and full of oil.

“Don’t thet beat anything in the hull world?” observed Pop Baker. “An’ thet door hooked up ez keerful ez usual. Now I never calkilated ter own sech a ’lumination ez thet wull shorely make. Hain’t that purty? Dern it! it air too fine ter dirty up. It jes does me good ter see it settin’ roun’. Whar’s my old one?”

He turned about, with his pine stick still blazing high. On his bed was a new patchwork quilt. In his arm-chair was a patchwork cushion. The table on which he had that morning left some very dirty dishes was spread with a new red oil-cloth, and on it were sundry parcels and covered pans.

“Sandy Claws hev gone inter the feedin’ business, hit ’pears like. Waal, I’m seventy-odd, ’n’ he never lit in on me afore. Shorely we live ter l’arn these hyah dayses.”

Delighted, he uncovered fresh bread and pies and cake, and a cold roasted rabbit. He lighted his tin lamp, and stirred up heartsome fire of great logs. The cabin glowed and grew gloriously warm. A friendly cricket chirped upon the hearth as he ate heartily and finally set out a large stone pitcher of hard cider. He poured in some molasses and then thrust an iron poker through the red embers. On Pop Baker’s face was a beautiful and tender light, in his blue eyes great love and faith in his fellow-men. The Christmas glow was in his heart, the Christmas peace brooding over him.

Then, and only then, he carefully pulled up a chair and unwrapped the little box Dink Smith had given him. It perched saucily upon the edge of the chair, and Pop sat down before it. He cut a long pine sliver carefully, and solemnly and breathlessly he touched the frail little wire fastening. Zip! it was open! There jumped up a rosy-faced, smiling jack-in-the-box with a fringe of gray hair and a perky chin-beard. It stared right saucily at Pop Baker and with the utmost indifference to his opinion. As for Pop, he was so amazed that he had no words. He stared and he retreated and he advanced, wholly fascinated. Then he put his hands down on his knees and he roared with laughter.

“Waal, I’m jes jee-whizzled ef hit ain’t my pictur’ ter a T! Sandy Claws must hev spotted me. An’ I got on a blue nightgownd with posies on it. Hain’t yer ol’ Pop Baker dyked out fer Christmas? Waal, I never would hev b’lieved it, not ef ye’d told me fer years an’ years; but thar I am, an’ whut am I goin’ ter do but b’lieve it? Waal, whut next? Do I shet up any more in thet box, or do I sleep a-standin’?”

He examined the toy with cautious fingers, but soon discovered the workings of the spring. At last he gently closed the box and deposited the precious thing beside the precious cheap glass lamp on the mantel-shelf.

“I couldn’t stan’ Sandy Claws a-doin’ of much more,” he said reverently, “er the Almighty thet air marchin’ erlong them stars. I calkilate them two pussons air erbout the same, me not bein’ up much in religion. Whut in the dickens air up? Air my house on fire? Woo-o-o!”

For a bucket or two of water was suddenly poured down his big chimney, raising a thick white steam. As this died away, a long pole let down an old basket, and, with a violent lurch from above, the contents tumbled far out on the bare floor. It was a shrieking, howling black puppy, a beautiful curly little creature that trembled like a leaf when Pop Baker jumped to its rescue and folded it in his arms.

“Dern yer buttons up yan! would ye bake the dawg a-playin’ of yer Sandy Claws? This air is shorely Jimpsey’s doin’s. Waal, they needn’t ’a’ put my fire out, need they, leetle Christmas? By gum, hain’t he a beauty? Sech thick ha’r! I never hev seen sech a pup. I bet he’s got sense; I bet he’s pure breed out o’ suthin’ ’sides them sneakin’ ol’ hill houn’s. Thar, ye jes lie on my bed while I sees who air playin’ Sandy Claws on ter my roof. Oh, I hears ye goin’ rattlin’ down my clapboards, I does! Ye means well, ye means well. Ef this here hain’t a Christmas ter be marked with a stone! The Lord bless ’em all! I’m gittin’ ter be ol’, but ol’ age air the bestes’ time, the merries’, free time. Sandy Claws never come a-nigh me tell now, an’ I ’preciates hit. I likes the lamp, an’ I likes thet pictur’ of me; but this hyah leetle pup—it’s a livin’, breathin’ thing, an’ it comes right nigh ter my heart. Seems like I got ’most everything thar war in the hull world ter git, Mr. Sandy Claws er the Almighty, which air might’ nigh the same thing. I thanks ye, wharever ye air.”

The Christmas midnight, still solemn and holy, was on the hills. The old man slept calmly in the red light of smoldering embers. The jack-in-the-box had jumped out to see the commotion of the night before, and kept its stiff wooden arms extended toward him in benediction. Close, very close to the old man, one of whose work-worn hands lay on the thick curly fur, slept the fat little puppy that was to be his constant and faithful companion in the days to come.