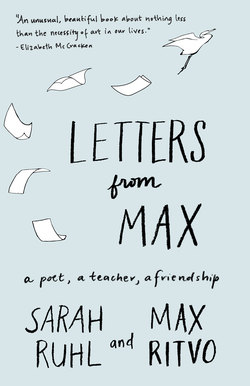

Читать книгу Letters from Max - Sarah Ruhl - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

Max Ritvo began as my student. I met Max when he was a senior at Yale. This is how he began his application to get into my playwriting workshop:

Dear Professor Ruhl,

Thanks for reading this application. My name is Max Ritvo—I’m a senior English major in the Creative Writing Concentration. All I want to do is write.

His application said that he was a poet and a comedian, part of an experimental comedy troupe. A poet and he’s funny? Huh. I reread his application, which had been left to stew in the “no” pile because he’d never written a play before.

And because funny poets are a rare and wonderful species of human being, I moved Max to the “yes” pile, despite his lack of experience writing plays. It is hard to imagine now that Max’s application could ever have remained in any other pile—a strange parallel universe in which I never met Max.

Max walked into my first class and it was as though an ancient light bulb hovered over his head, illuminating the room. Skinny to the point of worry, eyes luminous blue and large, even larger under his thick glasses. His eyes (both magnified and magnifying) were especially animated after he’d amused someone, anyone; with a hangdog look, he’d gaze up from behind his spectacles to see if the joke had found a target. His voice: surprisingly booming for so slight a frame. Some rarefied combination of a young Mike Nichols and an old John Keats, he seemed eighty years old and not from this century. Who is this boy? I wondered. He seemed to have read everything, from Vedic texts to contemporary poetry, and yet he had the air of a playful child.

The first missive I received from Max in my inbox began like this:

Dear Professor Ruhl,

I am writing because, before shopping period had even begun or I had even realized that this wonderful class existed, I booked tickets for Einstein on the Beach at the Brooklyn Academy of Music for this coming Friday.

Little did he know that I had longed to see Einstein on the Beach, had tried in fact to get a ticket, but it was sold out. Nothing could have been more delightful to me than a student who had the foresight to book tickets to a difficult and avant-garde theatrical epic. Max went on to apologize and ask permission to miss a class. I told Max that he must go, and I asked him for a short report (no more than five minutes) on the experience of seeing the show. I said maybe he could join us for the first part of class, then hightail it to Brooklyn to hear the great Philip Glass score.

Max wrote back, “Dear Sarah” (it took us two letters to drop the institutional formalities):

The show starts at seven. I’m worried if I leave later I won’t have time to properly get from Grand Central to eat something! The show is four hours long and I have to eat in a really regimented way to keep my weight up as a result of the cancer/chemotherapy I had in high school—more on that some other time.

I now had part of my answer as to why Max was different from the other students, why life and death seemed to hover near him, why (beyond being a poet) he’d already contemplated the big metaphysical questions, why he was so skinny. Max went on:

I would really love to take you up on your offer of some post-graduating advice. What days are you in New Haven, and when would it be convenient for you to be a sage for a half hour?

The following week, Max, as promised, delivered an insightful and detailed sermon to the class on Philip Glass and Robert Wilson. He was to have spoken for five minutes—he spoke for about an hour without stopping. (I later learned that a bright young woman in the class was horrified that a man was taking up an hour of her time with a lecture on Philip Glass; she was to become one of his best friends.) In class, Max had boundless enthusiasm. He had highly refined irony without ever being cynical. And if he was aware that his brain made connections ten times faster than most of his peers, he didn’t show it; he just seemed happy to be in such good company.

I met with Max after class at the local bookstore-café, Atticus, where we sat at the counter and ate black bean soup. Max ate slowly, with difficulty, and explained that in high school he’d had Ewing’s sarcoma, a rare pediatric cancer, and the chemotherapy made his digestion iffy. He explained that he was in remission and slowly finished three spoonfuls of the soup. Then he put his spoon down, and spoke about his dreams of becoming a poet, resting here and there to speak about the trials of love. (A girl was probably plaguing him at the time. A girl was often plaguing him.)

The semester wore on, with more deliciously coined phrases from Max in class (phrases like “theatrical onanism” and “lyric complicity”) and more of the same leaves falling on the same gothic campus. Then, in October, another email from Max, addressed to me and to the teaching assistant, Amelia:

Dearest Sarah and Amelia,

I write with sad news. Today was my cancer scanning day and an artifact was discovered in my right chest. We are waiting for more testing and surgical biopsy, but it is possible that this is a recurrence of my cancer. I have every intention of carrying on with my work—I just wanted to forewarn you that there might be some difficulties on the horizon. I can’t say how much you’ve both come to mean to me in my short time learning from you. If nothing else, maybe we’ll squeeze a great play out of whatever comes of this.

Gratefully,

Max

The small class and I were heartbroken.

A hurricane was about to arrive in New York City, and Max was about to go into surgery. The conversations Max and I had about art and life took on a new urgency, and our correspondence began in earnest.