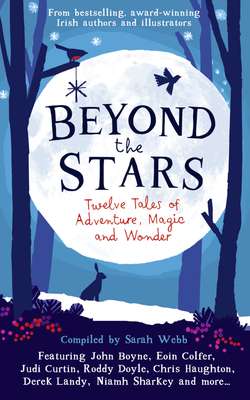

Читать книгу Beyond The Stars - Sarah Webb - Страница 10

Оглавление

John Boyne is the author of several novels for adults and younger readers, including the international bestseller and award-winning The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas, which was later adapted into a major motion picture. ‘The Brockets Get a Dog’ was inspired by his bestselling The Terrible Thing that Happened to Barnaby Brocket. John Boyne’s novels are published in forty-seven languages. John lives in Dublin.

Paul Howard’s charming illustrations have won him acclaim from both the publishing industry and children across the world. He illustrated Allan Ahlberg’s The Bravest Ever Bear, which won the Blue Peter Book Award. Paul lives in Belfast with his wife, their three children and his ‘hairy baby’, Tiggy, a Jack Russell terrier who is very fond of sticks.

Despite the terrible weather – wind that blew grown men along the streets, rain that de-permed perms – animals came and went throughout the day at Dr Napangardi’s veterinary surgery, and Abigail Crumb, a disorganised girl at the best of times, found it hard to keep track of them all. She worked there after school every Tuesday, Thursday and all day Saturday, but no matter how hard she tried, she always made mistakes.

When the Mannerings from Lavender Bay came by to pick up their miniature schnauzer, Abigail presented them instead with a walrus cub, who’d been brought in to have his tusks realigned.

When the McDougalls from McDougall Street showed up to collect their Siamese cats, they were not happy to be handed a container filled with gerbils and a large bag of mixed seeds and dry vegetables that Abigail, in a moment of generosity, had decided to offer them at no extra cost.

The customers complained and Abigail got into trouble almost every day.

On this particular afternoon, as she battled her way through the storm to work, she knew that she was going to get a telling-off for forgetting to lock a chimpanzee’s cage earlier in the week – she had spent most of the next day cleaning bananas off the walls – and started to work on her defence.

I’m punctual, she thought. I’m honest. And the animals like me. She was so intent on thinking up reasons why she shouldn’t be fired that she almost collided with a small boy who was walking along in the opposite direction with the weight of the world on his shoulders. He was wearing an old-fashioned pair of pilot’s goggles on the top of his head, the sort of leather gloves you only ever see in war movies and he didn’t seem to mind the fact that he was getting wetter by the minute. She wanted to ask him why he looked so sad but there was no time and she marched on past him.

“You’ll have to pay more attention to what you’re doing,” said Dr Napangardi when he sat her down at the end of that day. “No one wants to take someone else’s pet home.”

And Abigail, who had a toucan, a koala bear and an elephant of her own, knew that this was true. Should one of them fall ill, she wouldn’t like him to be cured and simply handed to the first person who happened to walk through the doors. Abigail resolved to do better in future as she didn’t want to lose her job.

She needed the money, after all. She was saving up for a houdah.

Arriving home that evening, Abigail was surprised to find a small boy sitting in her living room, the same unhappy-looking chap who she’d met on the street earlier in the day. He was stroking her koala bear, who clung to his arm as if he was a eucalyptus tree, while feeding peanuts to her elephant. The elephant had taken a seated position in the living room, the one room in the house where he knew he was not allowed to be. Abigail’s toucan was observing all these developments from her perch with great interest.

“Hello,” Abigail said, and the boy turned to look at her, wiping his eyes with the back of his hand. “Is everything all right?”

“Yes, thank you,” said the boy.

“I’m Abigail Crumb,” said Abigail. “And who might you be?”

“Henry Brocket,” said the boy. “I’m a friend of Lucy’s. We’re in the same class at school.”

“Oh,” said Abigail. “Poor you. Where is Lucy anyway?”

Henry nodded in the direction of the staircase.

“Awful day, isn’t it?” said Abigail.

“Well, it is the middle of winter.”

“Still. Awful. You’re dressed like a pilot,” she added, pointing at his goggles and gloves, which were placed on the seat next to him. “Or you were anyway. Any particular reason?”

“I want to be a pilot when I grow up,” explained Henry.

“There’s good money in piloting,” said Abigail. “I could do with a little of that myself right now. I’m saving for a houdah.”

Henry frowned. “What’s a houdah?” he asked.

“If you don’t know, you should look it up,” said Abigail. “That’s what dictionaries are for. Lucy brought you home from school with her, I suppose? Are you expecting to be fed?”

Henry separated a handful of peanuts into two piles, giving one half to the elephant and keeping the other half for himself. (The toucan flew down briefly and stole one, then returned to his perch; the koala bear snoozed through the whole thing.) “No, thank you,” he replied. “I’m happy as I am.”

“You don’t look happy,” she said after a pause. “To be honest, you look a bit sad.”

“Well, yes,” admitted Henry. “I am a bit sad. But I don’t need you to cook me anything.”

“And a good job too,” said Abigail, marching upstairs to her bedroom just as her younger sister, Lucy, marched down.

“There’s a boy in our living room,” said Abigail. “He’s dressed like a pilot.”

“I know,” said Lucy. “He’s my friend Henry.”

“He was crying when I came in. Although he pretended that he wasn’t.”

“He’s depressed, that’s all,” said Lucy. “His dog died.”

“Oh,” said Abigail, wondering whether she should go back down and make him some macaroni and cheese to make up for it.

“I’m planning on cheering him up by showing him my fossil collection,” said Lucy, opening a box that contained nothing more than a collection of stones pulled from the back garden, but Abigail didn’t have the heart to point this out. “And I have a book to loan him,” she added, holding one up.

“Very good,” said Abigail. “Carry on then.”

Entering her bedroom, she opened the letter that Dr Napangardi had given her when she was leaving the surgery and looked at it sorrowfully. FINAL WARNING, it said across the top in big red letters. Abigail sighed.

She would have to be very careful if she wanted to keep her job. After all, houdahs weren’t cheap.

You might be wondering what a houdah is. A couple of months earlier, even Abigail didn’t know what a houdah was, but she knew that she wanted one. Back then she didn’t call it a houdah, of course. She called it “one of those big seats with a canopy over the top that I can put on the back of my elephant and ride him around Sydney on sunny days.” But then her father said “You mean a houdah,” and she’d stopped calling it that (the first thing) and started calling it that (the second thing) instead.

She’d seen one in a shop off Market Street and it cost three hundred dollars and she’d managed to save two hundred and eighty-seven so she wasn’t far off.

Downstairs, Lucy showed Henry her fossil collection and Henry had the good manners not to point out that he had rocks exactly like these in his back garden and had even been considering making a rock museum out of them, only his mother had told him that normal people didn’t play in the mud like that.

“How long have you had this elephant?” asked Henry, wondering what on earth his mother, Eleanor Brocket, would say if she knew that he was consorting with a family who kept such outlandish pets in the house.

“Oh, since he was a calf,” said Lucy. “A circus was visiting Sydney and they left without him. Abigail found him wandering the streets and brought him home.”

“Don’t your parents mind?” asked Henry.

“Oh no. They’re very accommodating people.”

“My parents would go mad if I brought an elephant home,” said Henry.

“Perhaps they wouldn’t notice?” suggested Lucy.

“But they do take up a lot of space.”

“Your parents?”

“No, elephants.”

“Well, are they observant?” asked Lucy.

“Elephants?”

“No, your parents.”

Henry thought about it. “I’m pretty sure they’d see him,” he said. He fed some more nuts to the elephant, held out his hand for the toucan, patted the koala bear on the head and popped a few nuts in his mouth. Then he sighed a little as the rain pounded on the window because he was still quite sad.

“Here’s a book to cheer you up,” said Lucy. “I think you’ll like it. It’s about a pilot. It might give you some ideas.”

Henry looked at the title page. It was called Biggles in the Baltic. The cover showed an illustration of a pilot seated behind his control panel, swooping down on a boat in the sea.

“I’m sorry about your dog,” said Lucy, wanting to pat Henry’s hand to console him but worrying that she might go bright red if she did.

“It’s all right,” said Henry, putting the book in his bag, thinking he might give it a go later. “He was quite an old dog. And he’d lived a good life.”

“Will you get another one?”

Henry shrugged. “I want to,” he said. “But my parents say that normal people don’t just get a new dog to replace a dead one. They say we need to go through a grieving process.”

“And how long will that take?”

“At least a year.”

“They want you to be sad for a whole year?” asked Lucy in astonishment.

“That’s what normal people do, according to them,” said Henry.

“Well then,” said Abigail and the two children turned round to see the older girl standing there, eavesdropping on their conversation. “Who wants to be normal if that’s the case?”

The following Saturday – no longer stormy, but still quite cold and damp – Abigail was in work when the Dimplefords from Bogota Avenue came in with their two dogs, Hound and Distinguished Lady.