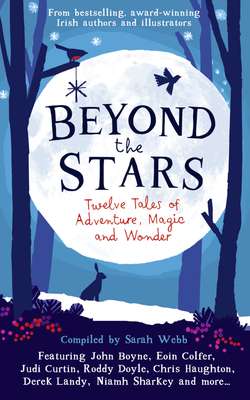

Читать книгу Beyond The Stars - Sarah Webb - Страница 8

MOSCOW – January, 1951:

ОглавлениеIt was cold. So cold. But the dog was used to it. The cold was a part of her. But the hunger – she could never get used to that. Although she had always been hungry.

She stood on the street, off the footpath, in the snow. She knew the humans would find it hard to see her – until it was too late. She was white, and very small. She could make herself seem even smaller, and the snow was fresh, new, still falling. The city’s dirt hadn’t spoilt it yet.

The dog watched the humans. They weren’t moving. They stood in a line outside the bakery, waiting for their turn to buy the bread that the dog could smell from where she stood. Like her, the humans were cold. Like her, they were used to it. Unlike her, they were tired, numb, half asleep.

She heard the car before she saw it. It had turned the corner but, still, she couldn’t see it until it came out of the falling snow. A black car. (All cars were black.) She made her move. She ran the short distance to the centre of the street, straight into the path of the car. There was a risk. She was the colour of the snow and the driver might not see her. But she was hungry. And she was loud.

She barked.

The driver heard the dog, then saw her. He braked, and the car stopped briefly, then started a sideways skid across the ice.

“Stupid dog!”

The car continued on its slow, unstoppable journey over the ice.

The women queuing outside the bakery turned in time to see the car. They watched as it hit another, parked car. There was no sign of the dog. No one had seen a dog. Some of the women went to help the driver, and the baker, a thin man with long arms, ran out of the shop.

“What happened?”

The dog made her move.

While all human eyes were fixed on the crashed car, she dashed back across the street. Her paws were tough, and moving over the ice was easy. She jumped and, with her teeth, she pulled a parcel from the top of a straw basket. It was a gamble – but she knew immediately that she had chosen well. Her nose told her, and her tongue against the paper bag told her: she had grabbed meat.

She’d been noticed.

“Look!”

“The cheek!”

She had to escape. Her size was useful again. She dashed through legs. Hands tried to grab her, and feet tried to kick. Women slid, and the baker ran back inside to get his gun. The dog was tempted to stop, to devour the meat right there – she was so hungry. But she kept going. She was almost clear.

She didn’t see the net, or the man holding the net. She felt it land on her back, and she felt it tangling her feet, her paws. She didn’t know what it was. But she did know she’d been caught.

She ate the meat as quickly as she could. She was still eating, snarling, when she was lifted in the net and carried to the cage in the back of the truck.

She had heard dogs howl before – of course she had. All her life she’d heard angry, frightened dogs. But never so many, and never under a low roof.

It was dark in the dog pound. There were no windows. But she could still see the other cages and the dogs. They were fighting against the chains that held them to the walls. Pulling, trying to bite through the iron links. And howling.

She howled too, and pulled. She had been here, locked up, for five days and nights. But she didn’t give up. She wouldn’t. She wanted to feel the ice under her paws again. She wanted to feel the freezing air, and the snow. She wanted to get back to the streets of the city, her wilderness, her proper life.

She saw the door open before she heard it. The door became a crack of light that got slowly wider, followed by the protests of the rusting hinges.

Followed by the humans.

There were two of them. Two males. One of them she’d seen before, the one who came every day and hit the cage bars with his wooden club before he filled their water bowls. The dog had bitten him the first day, and she’d felt the club on her back.

The other human she hadn’t seen before.

She watched them walk slowly between the cages, examining each dog. They walked straight past the bigger dogs and the dark-furred dogs, and stopped in front of a cage that contained a small white-furred dog, like her.

The dog, a female, sat quietly in her cage, the only dog not howling.

“This one,” said the stranger.

The man with the club unlocked the cage and took out the white dog. She didn’t attack or pull at her chain.

They moved again, the humans. And stopped again, at another white-furred dog.

“And this one,” said the stranger.

Again, the man with the club removed the chosen dog from her cage.

Here was her chance, she thought. Here was escape. She fought the urge to howl, and to throw herself at the bars of the cage.

She sat – she made herself sit still.

The two men walked past all of the large dogs. Nearer – they came nearer. Sit still, she told herself. Be still, sit still.

They stood in front of the dog.

“And this one.”

“This one bites,” said the man with the wooden club.

The dog stood – and wagged her tail.

“Surely not,” said the stranger. “You must be mistaken, comrade.”

“As you wish, comrade,” said the man with the club.

“She is perfect,” said the stranger. “We want the quiet ones.”

The cold air felt like food. She stood on the back of the truck as it raced out of the city. The buildings became smaller, and fewer. There were fewer of the billboards and banners that the humans seemed to love – ‘Glory to the Workers’, ‘Together We Go Forward’. Then there were no buildings or banners. They had left the city.

The dog looked back the way the truck had come. The road was long and straight, and she could see the city at its end. Far away, but still there. It stood out, with its own dark cloud hanging above it. She would find her way back easily, when the time came.

For now, she had the air. It went to her lungs, but also to her stomach. It filled her up and made her feel alive, and alert. There were six other dogs in the cage, but she was the only one standing. The others had tried it but had given up, and surrendered to the shaking of the truck. They lay on the truck bed. They were all white-furred, all very small.

The dog stood over them. She would be the leader.

One of the other dogs looked up at her.

“You look at something?” she said.

The other dog looked away. Good. She didn’t want to fight – not now. But she would if she had to. She was tough. Like the other dogs. They had all survived on the city’s streets. She would have to be the toughest.

The truck swerved suddenly to the left. The dog almost toppled; she nearly fell on to the others. One of them snarled and snapped. The truck moved over a rough, pot-holed track. Soon she felt the truck slow down, then stop. She saw a huge grey building, as big as a city building, but alone. It was partly hidden by trees.

The driver climbed out and came round to the back of the truck, and the cage. This was the same male human who had selected the dogs in the pound. She had heard his name. Pavel.

She wagged her tail and she barked.

Pavel opened the cage.

“Come, dogs,” he said. “Come, furry comrades. Welcome to the Institute.”

He had gathered their seven leashes into one hand, and now he pulled gently. He coaxed them to the edge of the truck bed until they had to jump.

The standing dog went first.

“Good dog.”

The others followed. Pavel patted their backs as they gathered around his feet. She stopped herself; she didn’t bite his hand. One of the other dogs, however, snapped at the human’s wrist. He cried out, shocked.

“Stupid dog!”

He examined his wrist.

“You will not be staying.”

He picked up the dog and pushed her, almost threw her, back into the cage. The steel of the lock screeched as he pushed it into place. It was a sound like pain.

Pavel examined his wrist again.

“No blood,” he said. “Come, dogs.”

He led them across the snow to a large metal door. The dog noticed a sign on the wall, a picture of something flying through a cloud, and she wondered why they’d been brought there.

Pavel pulled open the door, and they were now in a dark, damp corridor. The dogs fought against the leashes. They fought each other. She snapped at a dog who tried to get ahead of her. The other dog yelped and fell back. She was at the front. No other dog tried to pass.

They came to the end of the corridor and Pavel pushed open another metal door. They were now in a much brighter room. There were big windows along the high walls, and sunlight broke through the snow that lay on top of the windows in the ceiling.

And cages. There were cages here too, in the centre of the room, piled neatly on top of each other. There were rows of them, like one of the human buildings in the city. The dog could see that the cages were clean and shining. And empty.

More humans, all of them wearing white coats, came towards the dogs and surrounded them. They got down on their knees and patted the dogs. They laughed and looked excited.

A female white coat – Pavel called her Svetlana – stared into the dog’s eyes.

“This one I call Tsygan,” she said. “Gypsy.”

The dog had never had a name before. She had never belonged to a human, or been inside a human home.

The white coat, Svetlana, held Tsygan’s head. Tsygan didn’t bite her.

“You have had a tough life, I think,” said Svetlana.

Another human, an older one, arrived and, immediately, the others stood and stopped looking excited. Tsygan could tell this new human was the leader.

He spoke to Pavel.

“All female, yes?”

“Female?” said Pavel. “I was not told this, Comrade Gazenko.”

“Does no one ever listen?” said Gazenko.

“I am sorry, comrade doctor,” said Pavel.

“But why must they be female?” Svetlana asked.

“You will see tomorrow,” said Gazenko. “They are all light-furred, yes?”

“Yes, comrade.”

“Before you ask why,” said Gazenko, “it is because of the cameras. The dark ones cannot be detected. Now, feed and cage them. Selection starts tomorrow morning.”

*

Tsygan woke. It was dark. Another dog yelped in her sleep. There was no other noise. The white coats weren’t there.

She slept, she woke, she drank water from the bowl in her cage. It was still dark. She slept again.

She woke.

The white coats had arrived. They moved around the room, they sat and examined papers, they stood at machines. There was no laughter. It was not like the day before. Tsygan knew this was an important day, a day to be careful.

The little dog in the cage beside Tsygan whispered.

“Why are we here?”

“I do not know,” said Tsygan.

“My name is Dezik,” said the little dog.

Tsygan didn’t answer her. They heard the older white coat, Gazenko.

“No food until after testing,” he said.

“What is testing?” Dezik whispered.

Tsygan looked at her. She was younger than Tsygan, and frightened.

“I do not know,” said Tsygan.

Something in her, a feeling, nudged her to say more.

“Do not be frightened, Dezik,” she said.

All the dogs were taken from their cages and brought to a corner of the bright room.

Pavel lifted Tsygan. He put her on to a metal basket. Tsygan had seen machines just like this before, in many of the shops in the city. They were used to weigh meat and other food. But why were the white coats weighing Tsygan? She wanted to jump, to bite, to run. But she stayed calm, she sat still.

Gazenko gazed over his glasses at the dial.

“Eight kilos,” he announced.

“Good dog,” said Pavel, as he lifted Tsygan out.

Tsygan knew she’d passed a test.

Another dog was lifted, and weighed.

“Ten kilos,” said Gazenko. “Too heavy.”

The dog was taken away.

The little dog, Dezik, was once again beside Tsygan.

“What if I am too heavy?” she whispered.

Tsygan looked at the little dog.

“Dezik,” she whispered. “You are smaller than me. Do not worry.”

“What if I am too small?”

“Don’t worry.”

Dezik and other dogs were weighed. No more dogs were taken away.

“This is good?” Dezik asked.

“I think so,” Tsygan whispered.

Large bowls of water were placed in front of the dogs and a the white coat stood with each one as they drank and drank until the bowls were empty.

“Now, comrades,” said Gazenko. “The time has come to explain the male-female issue.”

He pointed at Tsygan.

“This one I like,” he said. “Female, yes?”

“Yes, comrade.”

“And this one,” said Gazenko, pointing at the last remaining male dog, Boris. “Dress them in their suits.”

Two of the female white coats dressed Tsygan. She didn’t bite or pull away from them. They pulled something, some garment, over her hind legs, and up across her back.

“It is like a nappy,” said Svetlana.

The other white coat laughed.

They pulled another garment over her head. She could see nothing for some seconds. A human hand went past her mouth, and she was tempted to snap. But then her head came through a hole and she could see again.

“No helmet, comrade doctor?” said a white coat.

“No,” said Gazenko. “The helmets are not yet ready.”

There were metal rings attached to the garment – the suit.

Pavel and Svetlana made Tsygan stand in a metal box. The metal box was like the weighing scales she had sat in earlier, but it was flat. There were hooks on the side of the box and Svetlana attached these to the rings on Tsygan’s suit. This worried Tsygan but Svetlana’s pats and whispers kept her calm.

“Don’t worry, Tsygan,” she said. “Good girl.”

The male dog, Boris, was also standing in his own metal box.

“Pavel,” said Gazenko. “Stand here.”

Tsygan watched Pavel move across to the other box and stand in front of Boris.

“Now,” said Gazenko. “The dogs are full of water, yes?”

“Yes, comrade doctor.”

“Very good,” said Gazenko. “Commence vibration.”

The boxes started to move. Tsygan could feel the box shifting under her feet. The box made little movements, back and forth, and shook. She almost fell but she put her feet further apart and stayed upright. The movements got faster. Tsygan felt like she was being shaken by rough human hands. Was this testing? she wondered. She didn’t like it. But she fought the urge to lie down – and she fought the urge to pee.

“Increase,” Gazenko shouted, over the noise of the vibrating boxes. “Faster.”

The vibration increased and, almost as bad, so did the noise. Tsygan had to pee; she couldn’t stop herself. She looked quickly at the floor of the box – no pee. The pee had been trapped in the suit.

She heard laughter now, and cheerful human screams. She looked quickly across at the other dog, Boris, and saw that his pee had not been trapped. It was shooting up in the air, and Pavel was drenched. He had jumped away from the jet of pee, and he was laughing, like the other white coats, including the leader, Gazenko.

The boxes slowed – and stopped. Tsygan sat, then lay down in the box. She felt sick – but also pleased. Another test I’ve passed, she thought.

“So, Pavel,” said Gazenko. “Now you understand why our cosmonauts must be female.”

“Yes, comrade doctor.”

“All males are disqualified. Agreed?”

“Absolute agreement, comrade doctor.”

“A rocket full of dog pee,” said Gazenko. “That is not a good idea.”

As Pavel and Gazenko spoke, the female white coat, Svetlana, unhooked Tsygan and put her gently on the floor in front of a bowl of water.

Dezik was beside her.

“That is testing?” she asked.

“Yes,” Tsygan whispered.

“What is cosmonaut?” Dezik asked.

“I do not know,” said Tsygan. “But I think we will find out soon.”

She shook herself, then drank. She yawned, and lay down on the floor. And slept.

On August the 15th, 1951, after eight months of ‘testing’, Tsygan and Dezik became the first living beings to go into space. Their rocket, which was launched from a space station in Kazakhstan, went to a height of sixty-two miles above the ground. It was a short flight, and the dogs didn’t go into orbit.

They survived.

Tsygan never flew again. Dezik did, exactly a week later, and, sadly, she died when the parachute holding her capsule failed to open.

Between 1951 and 1961, many more Russian dogs were sent into space, including the most famous, Laika, who became the first living being to orbit Earth, in November, 1957.

Most of the dogs were found on the streets of Moscow. All of them were very small. All of them were female.