Читать книгу Apples from the Desert - Savyon Liebrecht - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеForeword

SEVERAL YEARS AGO I was one of about fifteen Jewish writers who met in Switzerland. Some were from Israel; others were from the diaspora—the United States, Britain, Canada, France, Germany, Brazil, Argentina. Our parents, grandparents, a few of us as babies, had probably spoken Russian, Yiddish, Polish, German.

We had those languages in our ears—those tones, inflections, accents—as we wrote in English, Portuguese, Spanish, Hebrew.

It was a wonderful meeting. But when I looked at the six Israeli participants—including Yehuda Amichai and Aharon Appelfield, whose work I loved and knew well—I couldn’t help asking,” But where are my Israeli sisters?”

The men, suddenly looking like my Russian-Jewish uncles caught in a not-so-terrible but embarrassing mistake, looked at one another, startled, and said, “Yes, yes, of course, we should . . . Yes, What about Celia? Dahlia?”

I am writing this perhaps ten years later. I am in Vietnam at a meeting with Vietnamese writers, editors, and publishers discussing a new copyright law. I know three or four of the poets here and their fine work. Among the thirty of them, just two are women. And again I have to ask, “Where are our Vietnamese sisters?”

In both cases, the women literary workers existed and could be found. But is there no end to the aggressive need to ask that question, “Where are the women writers?”

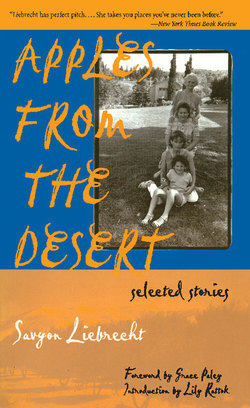

I am particularly happy to welcome Apples from the Desert by Savyon Liebrecht. These are wonderful stories. They are told by a woman who knows she is living in a country occupied by two nations. She knows she is a citizen, a speaker, in a country, Israel, where one nation, the Israeli, looks down on or looks coldly upon the other nation, the Palestinian, and the other language, Arabic. And then she tells everyday stories about what those cultural and political facts are doing to the characters and ordinary lives of both groups of people—the way in which both are deformed: one by pride, one by despair.

She understands, as well, the damage rendered by the chasm of misapprehension and mistrust between Ashkenazic and Sephardic Jews, between men and women, and between people of different generations—especially the older generation that lived through the Holocaust and the younger generation that would like to forget it.

She tells her stories with domestic irony—but it’s all straightforward history. The stories are elegantly understated and movingly personal—but they are also fierce pleas for understanding and justice. I compliment Savyon Liebrecht on her achievement. And I thank The Feminist Press again for bringing us women’s words in our own language and in translation from the rich other languages of the world.

Grace Paley

Hanoi, Vietnam

January 1998